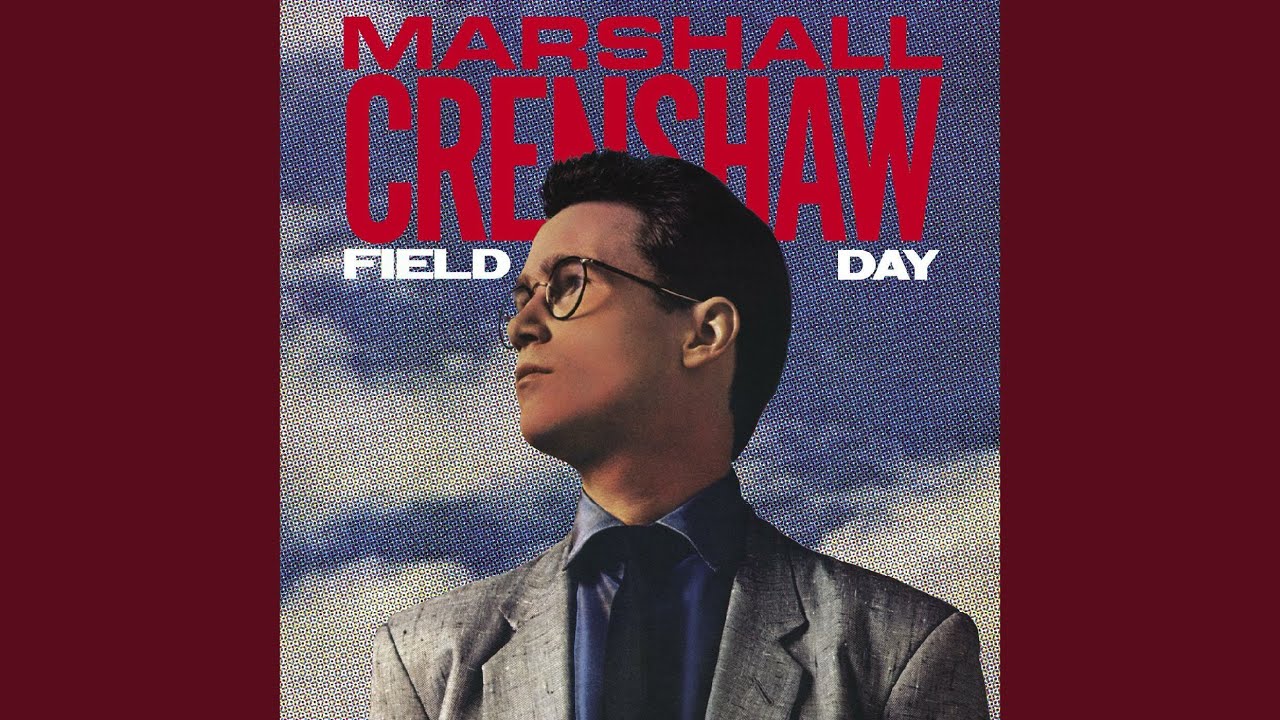

“The only way I could afford my ’66 Strat was to take the ‘66 neck off and sell it to a guy across the street, then go back to Manny’s and buy an ESP neck”: Marshall Crenshaw looks back on the making of his unsung, under-appreciated masterpiece, Field Day

With the help of producer-of-the-moment Steve Lillywhite, Marshall Crenshaw made the guitar album of his dreams. Critics, however, panned its production, halting his rising career. Four decades later, Field Day is finally being reappraised

“Of all my Warner Bros. albums, it’s the one I love the most, without a doubt. And maybe that’s because I took so much shit for it.”

When Marshall Crenshaw set out to make Field Day in early 1983, he was riding high on the success of his self-titled debut. Released the previous April, and recorded with his duo – bassist Chris Donato and Crenshaw’s brother, drummer Robert – Marshall Crenshaw was a sunny, power-pop confection, full of three-minute tunes whose styles recalled the artists that populated rock and roll’s late ’50s to early ’60s heyday, including Buddy Holly, Carl Perkins, and the Beatles.

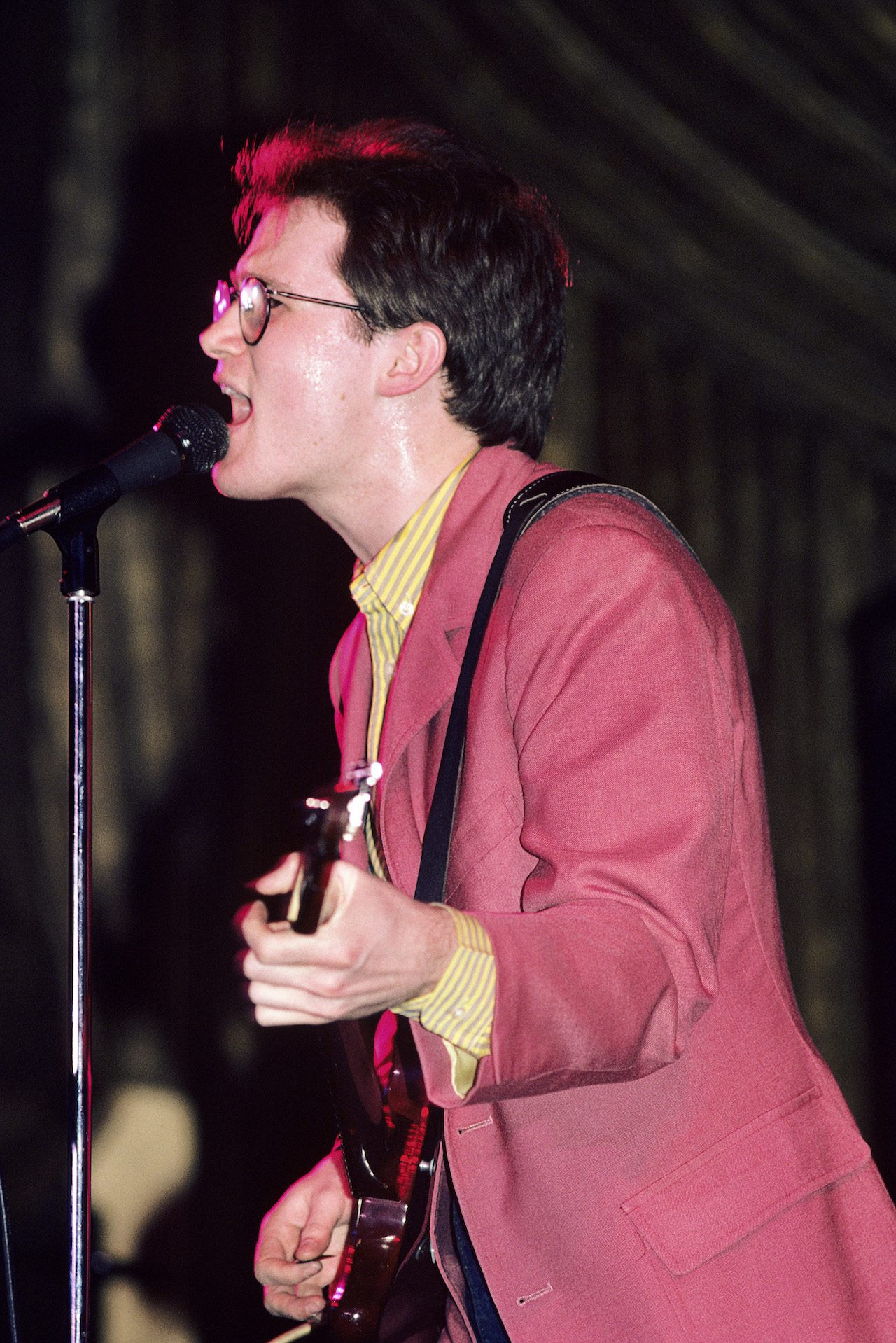

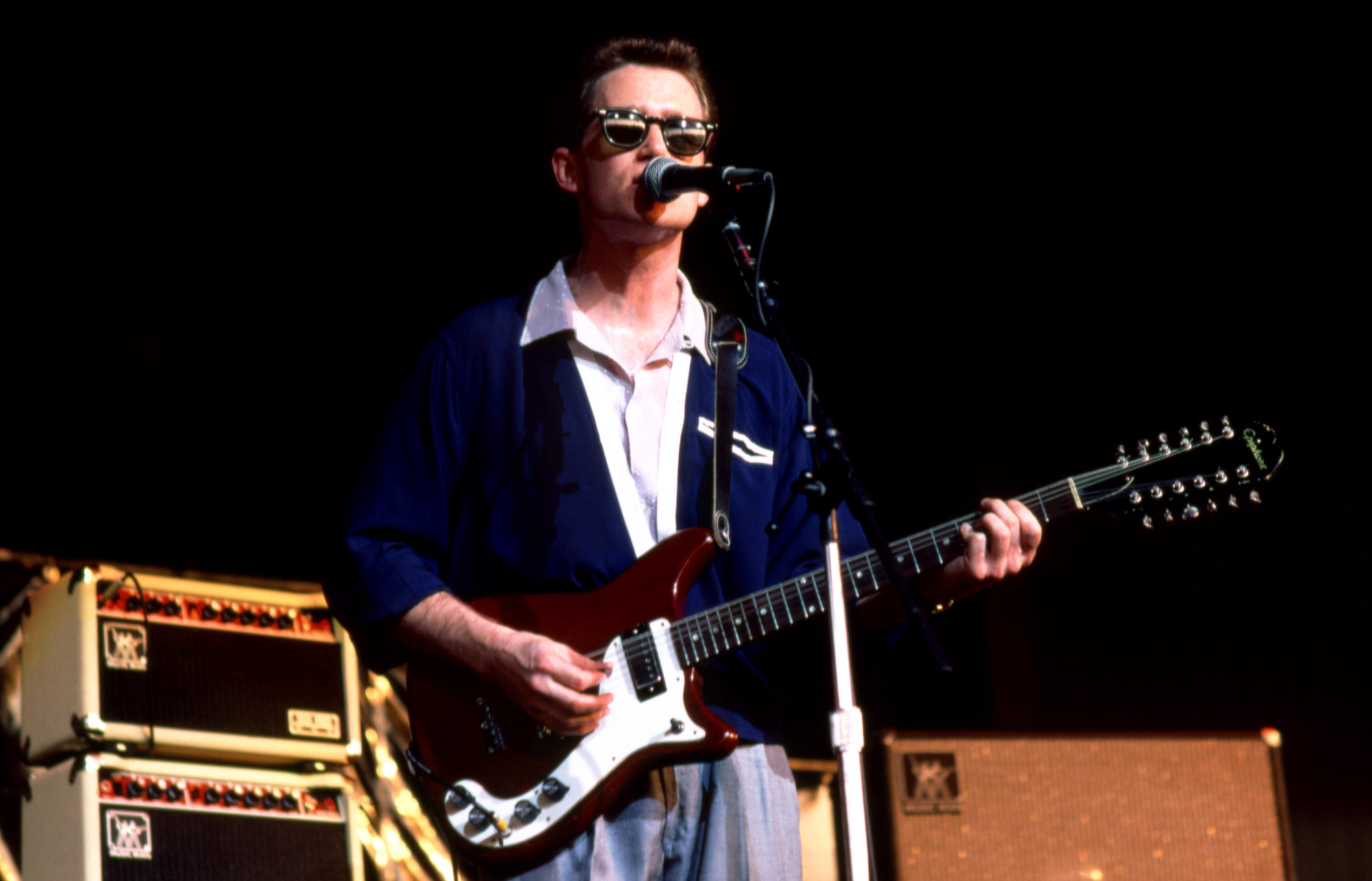

The album showed Crenshaw to be a fine songwriter and singer, but it was his guitar skills that proved to be his unlikely strong suit for a pop artist in those days of synth-driven new wave bands.

Chords, double-stops riffs and interstitial melodies were part and parcel of a Marshall Crenshaw guitar track, all of them woven together – with a healthy amount of slapback echo – to create something as ear-catching and fine as his plangent vocal lines. Remove the singing from a Crenshaw tune and you’ll have a guitar instrumental that’s every bit as enjoyable.

But one thing in particular bothered Crenshaw about his premiere album: the guitar sound. His producer, the former Brill Building songwriter Richard Gottehrer, had built each of its songs around layers of guitar tracks, including beds of as many as six acoustics that were pushed low in the mix to thicken the sound.

It was a far cry from the full-blooded rock-trio rave-ups that had made Crenshaw’s band one to watch when they launched in New York City’s clubs just a year or so before. It irked him enough that he decided his next album would be different.

“The whole process with all those layers of acoustics, I didn’t really want to do it that way,” Crenshaw says. “But Richard was there – I’d asked him to be there – so I just went with it.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“But then when it came time to do Field Day, I just said, ‘No, it’s not going to be that this time. It’s going to be this other thing that I wanted in the first place.’ Field Day was a reaction on my part to the first album.”

And that reaction was explosive. From Field Day’s opening track, Whenever You’re on My Mind, Crenshaw’s guitar playing bursts with a clarity and immediacy unlike anything heard on his debut, accompanied by the gated-reverb blast of Robert’s drum kit and Donato’s supple bass lines. Over the course of 10 tracks, Crenshaw and his band update their sound to power-pop perfection, a distinction that is duly celebrated in the recently released Field Day 40th Anniversary Expanded Edition.

In addition to the original album cuts, it offers six bonus tracks, including instrumental versions of Our Town and Monday Morning Rock that let his guitar work shine. Listening to these gems, it’s easy to understand why Crenshaw calls Field Day “the album I always wanted to make.”

Unfortunately, it wasn’t the follow-up record that critics had expected from an artist whose retro-tinged debut had so thoroughly delighted them. The backlash was swift, Warner’s reaction was rash, and the cost to Crenshaw was regrettable. Field Day became his career-defining album – just not the way he’d intended it to be.

The call to make a second album came much faster than Crenshaw had anticipated. The overwhelmingly positive reviews for his debut, combined with its commercial success – it hit number 50 during its six months on the Billboard charts and sold nearly 400,000 units, while the single Someday Someway reached 36 – convinced Warner Bros. to keep the momentum going.

“It was kind of a funny move to make a second album that soon after the first,” Crenshaw says. “We’d only just made the first album, but I thought, ‘Yeah, I love making records. Let’s go!’”

From the project’s outset, Crenshaw knew he wanted to work with Steve Lillywhite. By 1983, the British producer had made a name for himself helming celebrated albums by U.K. punk and new wave acts like Ultravox, Siouxsie and the Banshees, XTC, and the Psychedelic Furs.

“If you were paying attention to the English scene, or if you were in the clubs all the time like I was, you heard a lot of stuff from him that was very distinctive,” Crenshaw says. “Like Generals and Majors by XTC. It was like, ‘What the hell is that sound?’

But it was Lillywhite’s work with U2 that sealed the deal.

“It was because of I Will Follow,” Crenshaw says. “All the DJs in the clubs played that record. I could hear that there were very few instruments on it, but it had this magnificent sound. And I thought, ‘Him – we gotta get him. I can harness that thing that he’s doing and make that work for me.’ I thought he would just be perfect for what I wanted to do.”

Despite Crenshaw’s success, Lillywhite was too deep in the British scene for the guitarist to appear on his radar. “I wasn’t really aware of him,” the producer says over the phone. “I was in my U2 sort of bubble, and I hadn’t really done any American artists, so it was a great opportunity.”

The artist and producer quickly hit it off. “He was a lovely guy, and he had his brother on drums,” Lillywhite exclaims. “And, weirdly, he’s the only artist I think I’ve worked with where the brothers were not arguing all the time. I’ve worked with the Psychedelic Furs, where Richard and Tim Butler would go down to the pub and then come back and just fight. That’s what youngsters are like. But Marshall and Robert were fantastic.”

With Marshall, there was never a case of him coming to the studio without finished lyrics, which I had had for three years with Bono

Steve Lillywhite

Although Crenshaw admits he felt rushed to come up with new material, Lillywhite recalls that the songs were largely finished by the time he arrived.

“I’d been used to working with punk bands, who were not so prepared,” he says. “Whereas with Marshall, there was never a case of him coming to the studio without finished lyrics, which I had had for three years with Bono. With Marshall, it was like, ‘Wow, he’s got his lyrics finished!’”

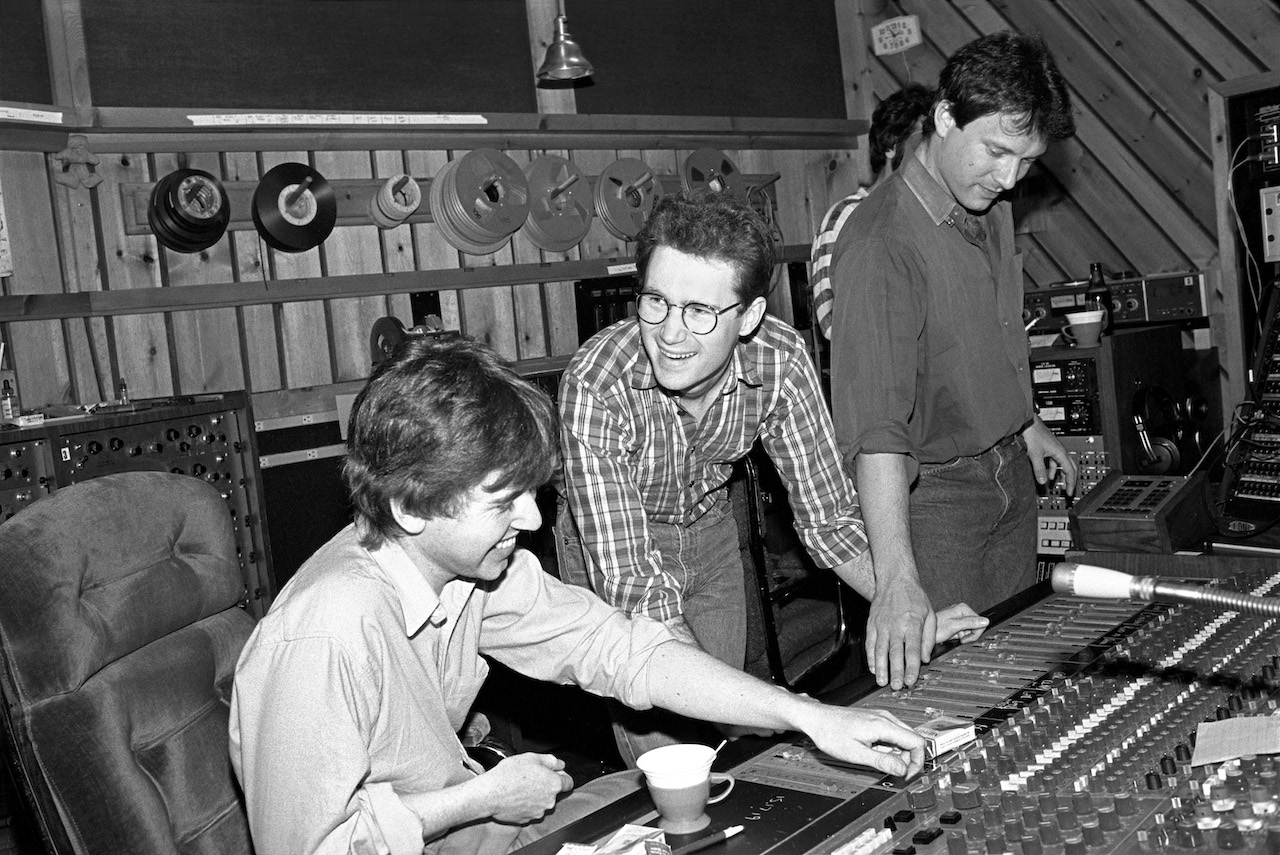

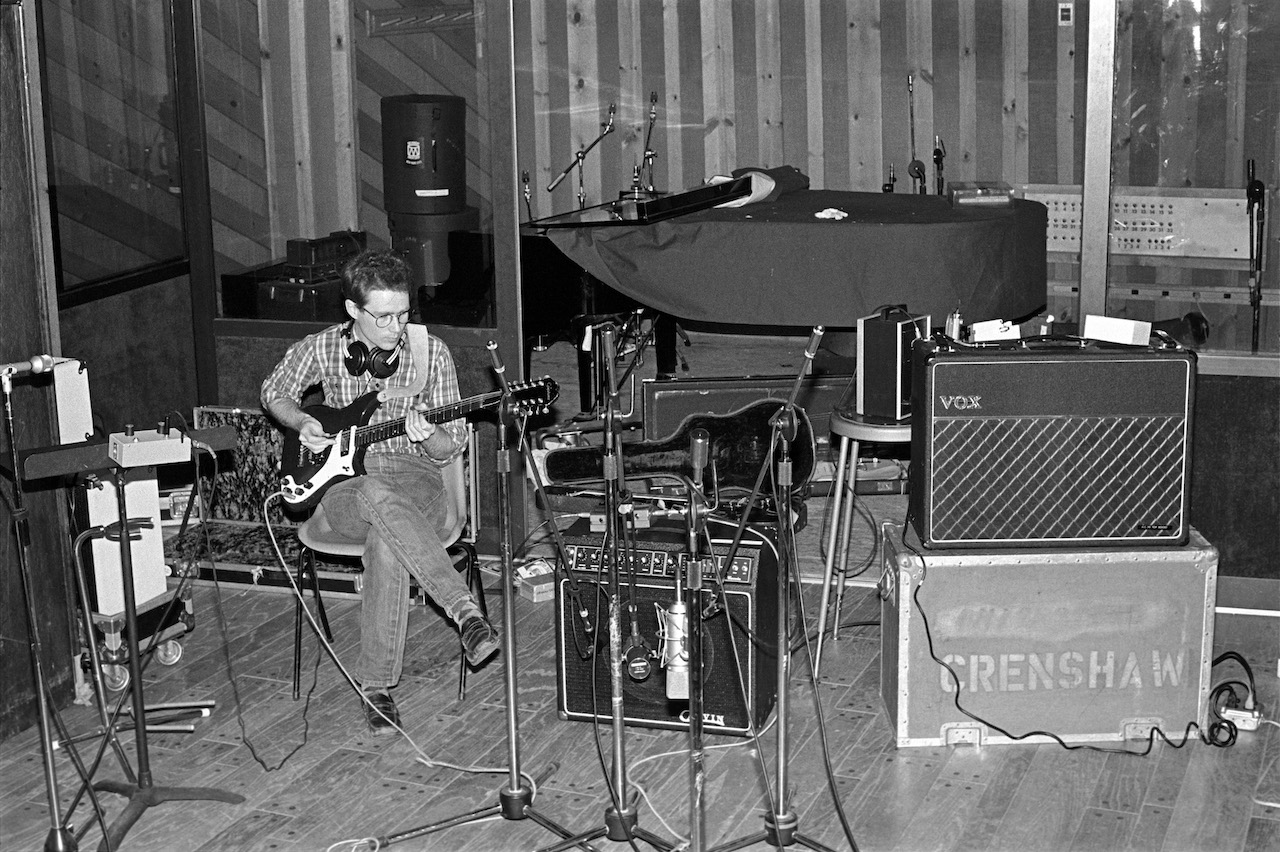

Checking into the Power Station – at the time a six-year-old state-of-the-art studio in Manhattan’s Hell’s Kitchen – Crenshaw’s band and Lillywhite settled in for what was, by all accounts, an efficient production, aided by Crenshaw’s preparedness, the musicians’ skills, and the production-line-style operation.

“First we chose a tempo and put the click track down,” Crenshaw explains. “I would do a guitar and guide vocal, and then we’d just start building it from there.” As he recalls, the album was completed in about five weeks. “It went pretty fast,” he remarks.

And yet, five weeks doesn’t seem particularly short when you consider the album has just 10 tracks. Add to that Crenshaw’s desire to keep overdubs to a minimum and it seems the record could have been completed in much less time.

As it turns out, Lillywhite’s tracking techniques meant the group never performed as a trio. “No. Never. There was no ensemble playing on the album,” Crenshaw confirms. “Not only that but the drum set was recorded drums first, and then cymbals. Isn’t that crazy?”

But it’s not so weird once you hear it from Lillywhite. “That sort of sound that I got is really good for the drums. But the way I miked the drums up, it wasn’t good for the cymbals,” he explains. “So in those days, I would record the cymbals separately because I could isolate the sounds better. And the room was very bright and echoey, so if you compress the room sound, you can sort of suck the room into your sound.”

It was a sound Crenshaw was especially enamored with, owing both to Lillywhite’s liberal use of gated reverb – a technique he’d popularized with Phil Collins on Peter Gabriel’s 1980 track, Intruder – and the Power Station itself.

“The sounds on Field Day are really organic sounds,” the guitarist says. “The Power Station was like a work of art inside. It’s all exposed wood, and it was one of the few places in New York where they still had old tube equipment in place – like, a ton of it. And so I think nearly everything on the album got cranked through those Pultec EQs at some point or another. I really, really love those.”

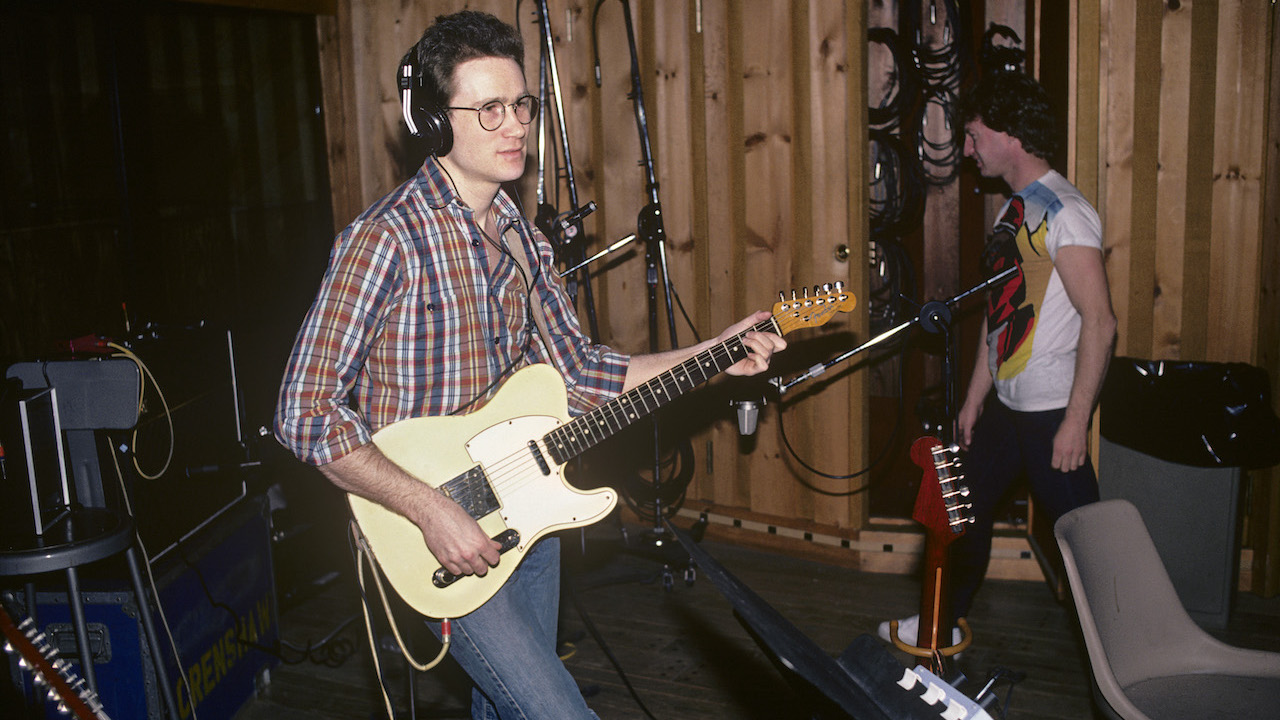

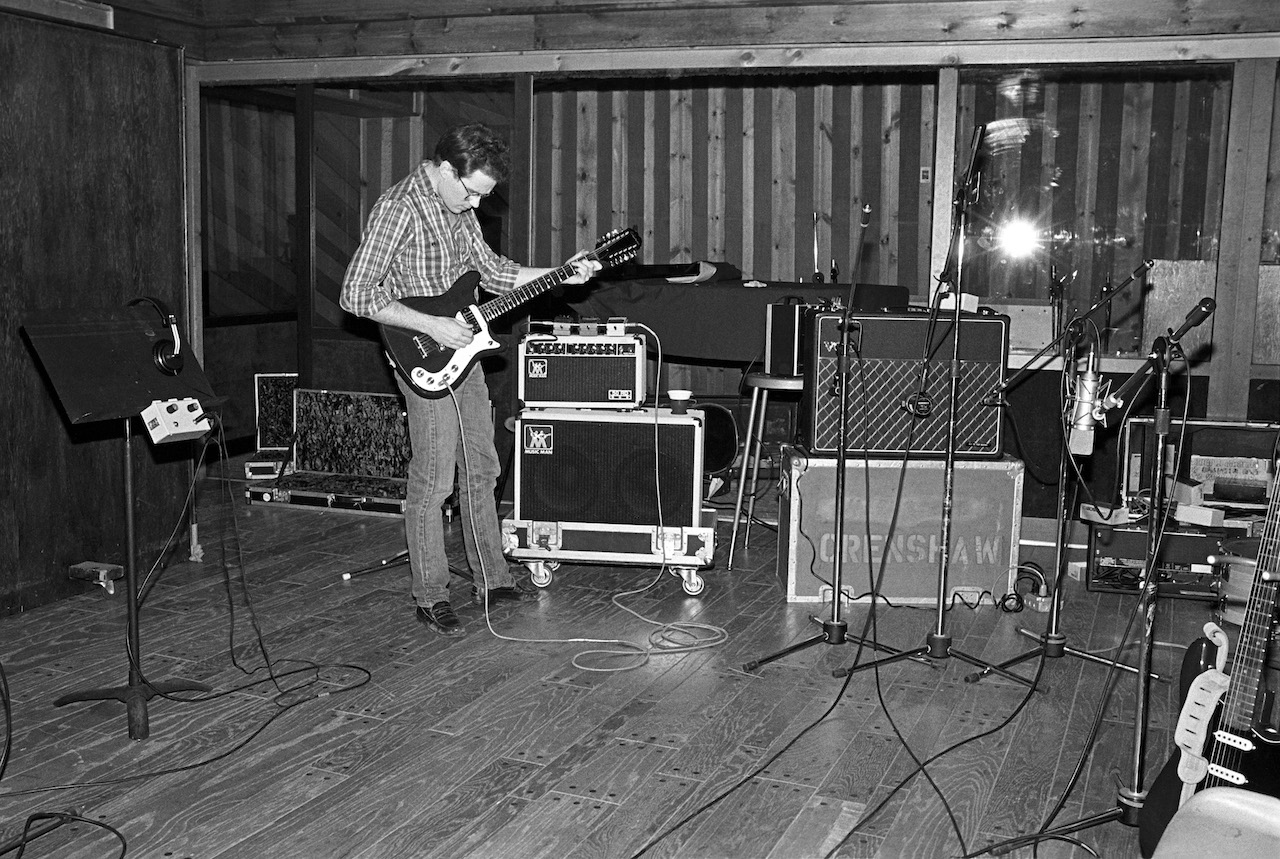

When tracking his guitar, Crenshaw aimed for single takes. “Once the drums were down, I would put on the main rhythm guitar, but I would always go for a complete take from start to finish, like I was playing it onstage,” he says. “I wanted to be straightforward all the way through and have that feeling of excitement building and grooving.”

Crenshaw came to the sessions with a small but varied arsenal of guitars and amps, including his main guitar, a 1966 Fender Strat that he received just out of high school from his cousin Chuck.

The only way I could afford it was to take the ’66 neck off and sell that to a guy across the street, and then go back across to the other side of the street and buy the ESP neck

“He served in the Air Force during the Vietnam war, and while he was over there he splurged and bought himself a Fender Stratocaster,” Crenshaw relates. “It was kind of a quirky one, because the neck was super skinny. I’ve never seen one like this on a Fender guitar before. It was almost like they were copying Mosrite for the Asian market. And I remember on the case it had a silver sticker that said, ‘Fender. Sold in S.E. Asia by the Tsang Fook Piano Company, Marina House, Hong Kong.’”

By the time of the Field Day sessions, the neck had been replaced with an ESP make “with kind of a ’55 Strat profile,” Crenshaw says. “I found it in Manny’s, or one of those other places on 48th Street. The only way I could afford it was to take the ’66 neck off and sell that to a guy across the street, and then go back across to the other side of the street and buy the ESP neck. Now the guitar is back to looking like it did when I first got it from my cousin, except I got a ’65 neck instead of a ’66, ’cause I hate those big headstocks on the Strat.”

In addition to the Strat, Crenshaw had an Epiphone Coronet with a P90 pickup, a Telecaster, and a guitar he’d purchased just before the sessions: a ’55 Gretsch Jet Fire Bird, heard on the songs Try and One Day With You.

“I dreamed of having one for years,” he says. “I’d seen Bo Diddley on the covers of his first two albums holding one, and I was like, ‘Where do I get one of those?’ Duane Eddy played one too. And those DeArmond pickups! I just always wanted the DeArmonds.”

For amps, he relied mostly on a Vox AC30 and a Fender Dual Showman. A Music Man RD-50 head and cabinet were put to use as well, while a Carvin combo was also present but likely not employed. Effects included Boss echo and chorus pedals.

“I always used a slap echo on my guitar instead of reverb,” he says. “I listened to a lot of rockabilly and I listened to Les Paul, and there was always slap echo on the guitar. I just fell in love with that sound, so I kept it on all the time.”

Sculpting the band’s sound, Lillywhite made the drums and guitar the most prominent aspects of the mix. Crenshaw largely left him alone.

“We would never discuss things too much,” the producer explains. “Because if I did my job and he did his job, there was just so much more room for joy.”

The joy is evident from the very first sound on the album: Crenshaw’s overdriven guitar riff to Whenever You’re on My Mind, the album’s lead single. The song is among the most infectious tunes in his catalog, or in the power-pop pantheon for that matter. Crenshaw wrote it years before making his first album, “but I kept it in my back pocket in case I needed it later,” he says.

If the recording sounds like Crenshaw and his band are having a blast, it’s because they are, and even indulging in a bit of juvenile fun.

“We decided to put satanic messages on the record,” he confesses with a grin. “I would just whisper and say things here and there.”

It doesn’t take an especially careful listening to hear a pair of indecipherable comments on Whenever You’re on My Mind.

The first occurs five seconds in. As Crenshaw explains, “Just before I went out to do that take, Scott Litt told me a dirty story about Robert Gordon, the rockabilly singer.” (A major player in the late-’70s rockabilly revival movement, Gordon had scored a hit with his recording of Crenshaw’s Someday Someway in 1981.) “Scott had gone down to Nashville with Robert and they had some adventures. And what I whisper at the beginning of the track is the punchline to the story, which was, ‘I think she dug it.’”

The second message, heard during the guitar solo, is a poke at Elvis Presley’s legendary appetite for cheeseburgers, which accounted for his enormous girth at the time of his death.

“In the control booth, we’d been talking about the Memphis Mafia,” Crenshaw says, referring to Presley’s ever-present entourage. “During the guitar solo, I could see my brother through the [studio booth] window, and I just yelled out, ‘Cheeseburger now!’”

Although Crenshaw was working to get away from the sound of his debut, he didn’t entirely abandon its early rock and soul trappings. Try, a heartfelt ballad in 12/8 time – a signature of the classic rock and roll era – adopts the shuffle rhythm of his early hit There She Goes Again.

“It’s the same drum beat, just slowed down,” Crenshaw confirms. “I copied that beat from a song called Backfield in Motion by Mel & Tim, a Chicago soul hit record when I was in high school. It’s also on It’s All Right by the Impressions.”

I just thought, ‘Okay, what would Danny Gatton play if he was here?’ I was trying to get in that ballpark

Likewise, One More Reason to Cry and One Day With You have a rockabilly flair, and the latter features a twanging solo full of double-stops. As Crenshaw explains, that spotlight was originally intended for his pal Danny Gatton, who was in town performing in Robert Gordon’s band.

“He and I were friends at that time and I invited him to come and play a solo on that song,” he relates. “And he said he would come, but he didn’t show up. So I just thought, ‘Okay, what would he play if he was here?’ I was trying to get in that ballpark.”

And then there’s What Time Is It. The only cover tune on the album, it’s a bona fide early ’60s classic co-written by Crenshaw’s former producer, Richard Gottehrer.

“I was kind of doing a shout-out to him because I only did one album with Richard and then I moved on,” Crenshaw explains. “And he really did a lot for me. I don’t want to say he discovered me, but he was the first person, with the kind of clout that he had, to open the door for me. So I had a sense that I owed something to him.

“But the other thing is that the song was a favorite of mine. So it’s a combination of those two things. Steve really arranged that. That’s him clicking his tongue for the [tick-tock] percussion.”

Lillywhite also provided the track with a more contemporary sound, adding backward reverb on the outro to create a wash of psychedelic reverie. “That song is a little art piece,” Crenshaw notes. “It’s kind of oddball, but nice.”

What really stands out on Field Day, though, is how Crenshaw’s sense of harmony and chromaticism had developed since his first album.

Surprises abound throughout the record, such as on the penultimate chord to the middle-eight in Try, where he substitutes an F for a D, moving out of the song’s key center. Or on the refrain to All I Know Right Now, where he shifts the song from D major to G major 7, and uses chord substitution to segue smoothly back to D.

“I’m just copying other people and their stuff that grabbed me,” Crenshaw explains. “I’m thinking in particular of Burt Bacharach. I heard a thousand of his songs when I was growing up. And then he had a couple of disciples, namely Brian Wilson and [R&B songwriter and producer] Thom Bell, two other writers I love.

“So I’m just trying in my own crude way to copy that, because I don’t really know the right chord forms all the time. I’m just trying to really go deep inside myself and come up with stuff that’ll engage people emotionally. And the songs from those writers – there’s a character to the music that had that effect on me, so I just figured I’d copy them.”

Given the ease and creativity with which the recordings took shape, Crenshaw says the sessions were “loads of fun,” and were often followed by after-hours entertainment. It was this late-night activity that inspired one of Field Day’s most upbeat songs, Monday Morning Rock. (And speaking of key changes, Crenshaw actually calls one out at the solo break.)

“We would go out at night after we were done. It’d be late at night, like, two in the morning, and everyone would head out. I remember a couple times going someplace and it would be broad daylight when we came out. So Monday Morning Rock – it was just an idea in my head.”

Perhaps the only song that gave Crenshaw any trouble was the closer, Hold It, which describes, rather unexpectedly, a fondness for hearing Michael Jackson on his radio.

While some listeners might have thought it was an attempt to appear contemporary – nothing was bigger than Jackson’s Thriller album in 1983 – Crenshaw says the call-out was heartfelt. “I really loved him and that Off the Wall album, especially Rock With You,” he says.

“I had the 45 and just listened to it obsessively. And I’d gotten Thriller when it came out and was just nuts over that.

“But that song was very, very hurriedly written. I wrote the lyrics while I was cutting the vocal. I was most certainly under the gun, because Steve was going to leave the next day, and I had to go someplace, too. I went out and recorded [Rock On] for [Superman III] at Giorgio Moroder’s house. So the album had to be finished and I couldn’t get Hold It together until finally I had no choice but to just grind it out.”

With recording complete, it was evident to Crenshaw and Lillywhite that they had achieved exactly what they had intended: a record that captured the trio with as much power as they had onstage. Thanks to what might now be thought of as the “limitations” of 24-track recording, they’d had to commit to various takes and sounds as they went along, with the result that Field Day was largely mixed direct to tape.

“I loved the two-inch 24-track format,” Lillywhite says. “It was just perfect, because it meant you had to make decisions and you could never get carried away with recording too much. I would always build a mix as I was recording. That way, every time you do something, you’re just adding to the mix. And then by the time you’ve finished it, the mix is done, because you’ve been mixing as you go.”

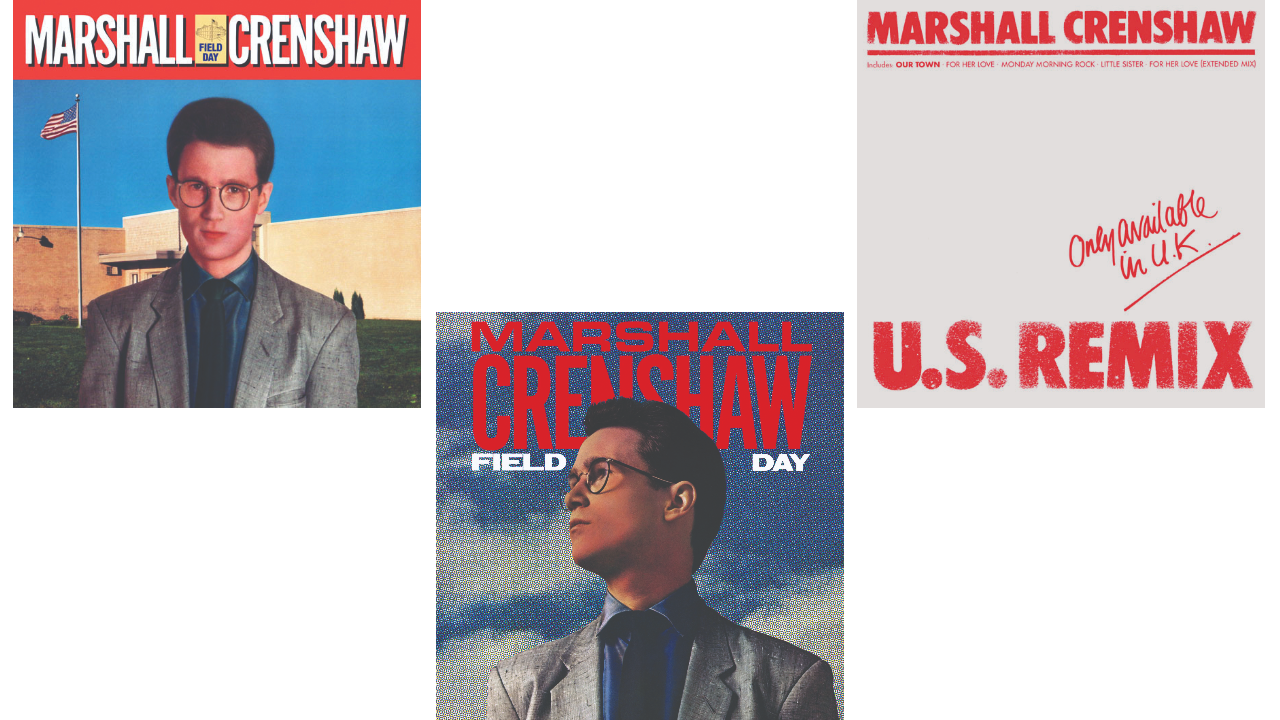

But even before Field Day’s release, signs of the trouble to come were foreshadowed in its cover image, a composite photo of the artist incongruously placed before a post-war-era public school building. It had been created without consulting Crenshaw, who was away on vacation after recording was completed.

He hated it on sight. “It’s supposed to be kind of tongue in cheek, with me standing in front of this building and the American flag and all that stuff,” he says. “But I just don’t think it’s a good picture.” However, since changing the cover would have delayed the album’s release, he grudgingly consented to it.

In April, two months before Field Day was issued, record buyers got an advance taste of Crenshaw’s new sound with the single release Whenever You’re on My Mind. Aided by a music video shot in England, it reached number three on Billboard’s Bubbling Under Hot 100 chart – an auspicious launch for the new phase of Crenshaw’s career.

But Field Day wouldn’t enjoy equal success. Released in June, the album spent just 14 weeks on the charts, where it peaked at 52. Blame it on the absence of a follow-up single (Field Day offered numerous contenders). Blame it on the album cover. But popular consensus says the problem was the music critics, who were almost unanimously put off by Crenshaw’s more current sound.

Robert Christgau’s review is a prime example. Although he graded Field Day an A+, ostensibly on behalf of its songwriting and performances, Christgau couldn’t get past the production, and devoted nearly the entirety of his 177-word review to it in damning praise: “With Steve Lillywhite doctoring Crenshaw’s efficient trio until it booms and echoes like cannons in a cathedral, the production doesn’t prove Marshall isn’t retro, though he isn’t. It proves that no matter how genuine your commitment to the present, you can look pretty stupid adjusting to fashion.”

“Usually you don’t have critics complaining about how something is produced,” Lillywhite offers wryly. “So I do remember being surprised by the response. There were all these comments about the ambience and the sound. I think people were expecting something more like his debut album and what they got was a step up, something much more sophisticated and thoughtful. It’s relatively aggressive as well. It’s quite in your face and it had attitude, and that’s a great thing to put on a record.”

Alarmed by the response, Warner Bros. quickly hired famed dance remixer John Luongo to create tamer-sounding versions of Our Town, For Her Love and Monday Morning Rock. Released as a 12-inch EP with “U.S. Remix” emblazoned on its front, the disc was an attempt to salvage what the label sensed was an artistic error. And despite having “Only Available in U.K.” prominently printed on its cover, the EP was readily available in the U.S., where “damage control” was essential.

“That was kind of foisted on me,” Crenshaw says of the EP, “And then Steve yelled at me. He was like, ‘Well, I could have done it. I would have done a better job of it.’ So it was somebody else’s thing, not mine. I just walked away from it.”

And he stayed away. Two years would pass before Crenshaw returned with Downtown, a darker, richer, and more country-roots affair, produced by T Bone Burnett and featuring performances by G.E. Smith, Tony Levin, and Mickey Curry. Noticeably absent among the album’s star-studded personnel were Donato and Robert Crenshaw, the latter of whom played drums on only two of Downtown’s 10 tracks.

“Well, you know, after Field Day, everything just really blew up,” Crenshaw explains. “The reaction to it just shocked me so much. I hated what the record company did with it. That’s a very dirty story. But, you know, I was completely fershimmeled. My mind was blown. So I just took a long break. And then I just kind of started from scratch again.”

If the critics were cruel, time has been kind to Field Day. Once beloved only by Crenshaw’s most die-hard fans, the album is now considered by many to be among his best works and one of rock’s great “undiscovered” treasures. If Crenshaw wanted to quickly move past the record in 1983, he had no reservations about revisiting it for its 40th anniversary or revising its awkward cover art.

“I just wanted to do justice to it,” he says. “That album is great. It’s the definitive one. It’s the first album where you can tell that I’m a guitar player. You can’t really tell that on the first album; you can’t hear my guitar. You can’t hear me and my sound on the guitar. Whereas on Field Day, the guitar is almost all you hear. And I love the guitar playing on it.”

- The 40th anniversary edition of Marshall Crenshaw's Field Day can be purchased or streamed now.

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.