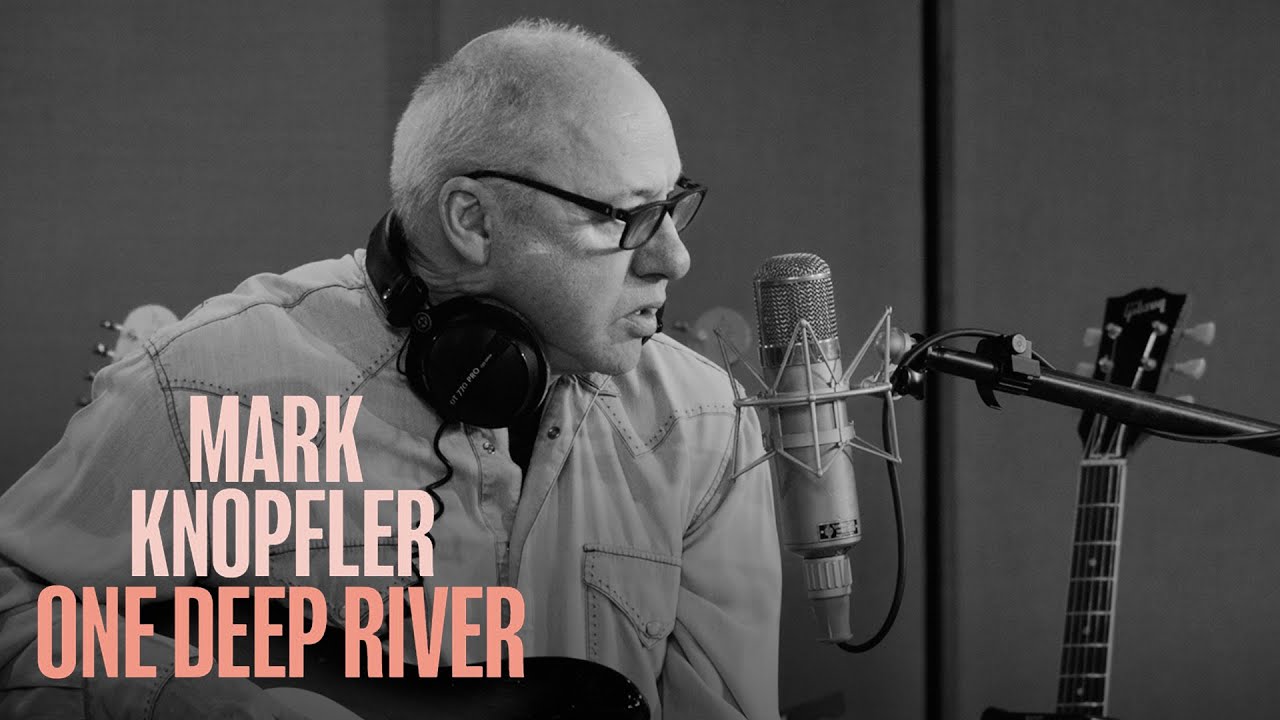

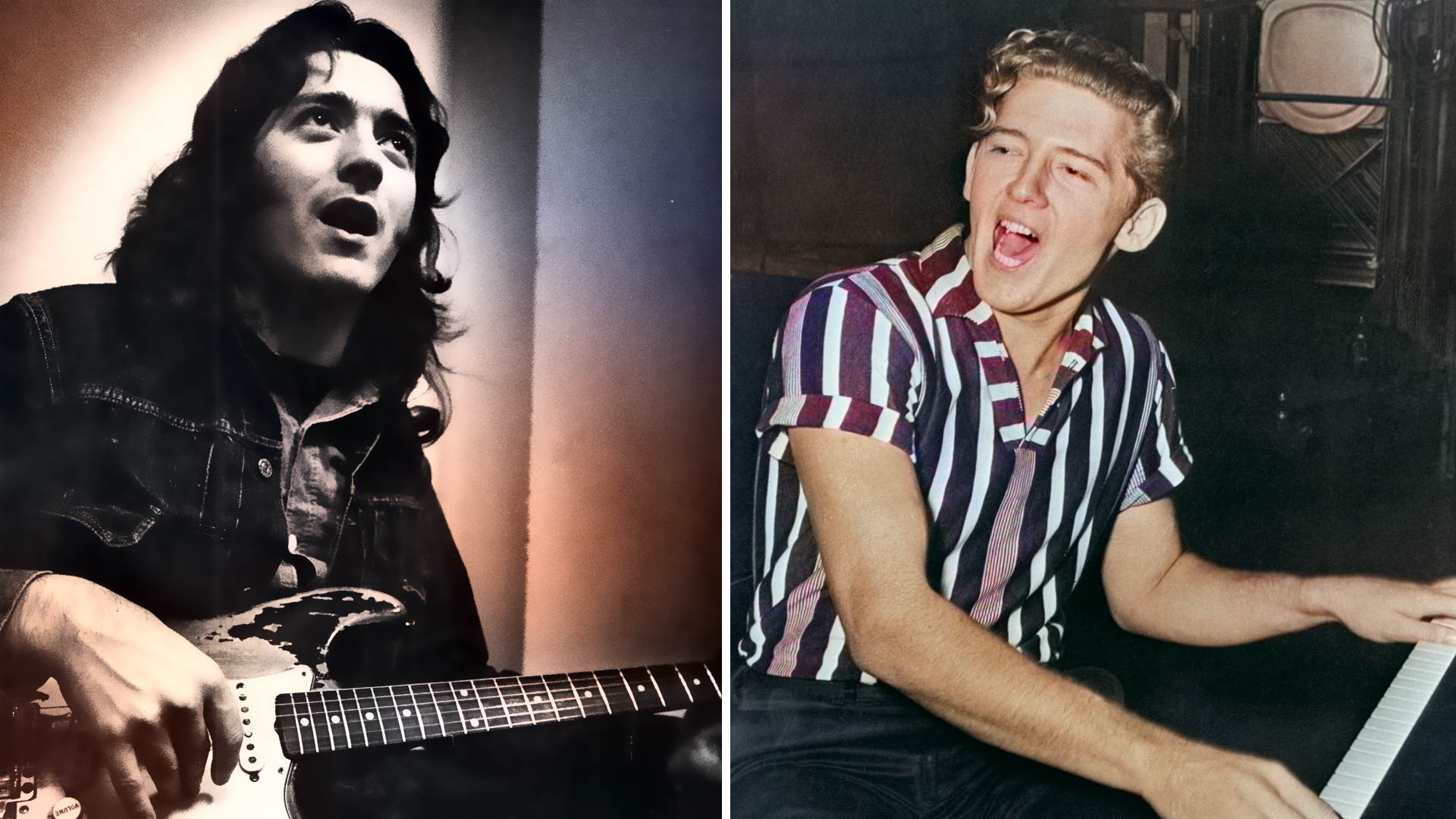

“Chet Atkins told me, ‘A guitar’s your friend for life. It’ll be your best friend.’ And they are. They’re wonderful companions”: Mark Knopfler on the guitars he couldn't send to auction, and that all-star version of Going Home

Following the release of One Deep River, Knopfler reflects on the guitars he’s loved – including his “serial number zero” Strat – the music that keeps his passion youthful, and how he’d like a do-over on that Dire Straits Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction

Talking with Mark Knopfler about guitars – what else? – is a bit like speaking with an unrepentant kid and a hardened member of GAA: Guitar Aficionados Anonymous.

“I still stop and look in a guitar shop window when I pass one on the street. I can’t walk past it,” Knopfler confesses via Zoom from his home in London. “And all the clichés – nose up against the glass, that whole thing. I suppose there were a lot of years where, instead of music being music and songs being a dream – a kid’s dream – it became work. It becomes your life. And I’m not alone there.

“So I have to try hard to keep it ‘teenage’ – to stay the kid about it. It’s an endlessly fascinating thing to be part of. And it goes on. History goes on.”

And this year Knopfler, now 74 and more than 45 years onward from his first album with Dire Straits, is adding a few chapters to his history.

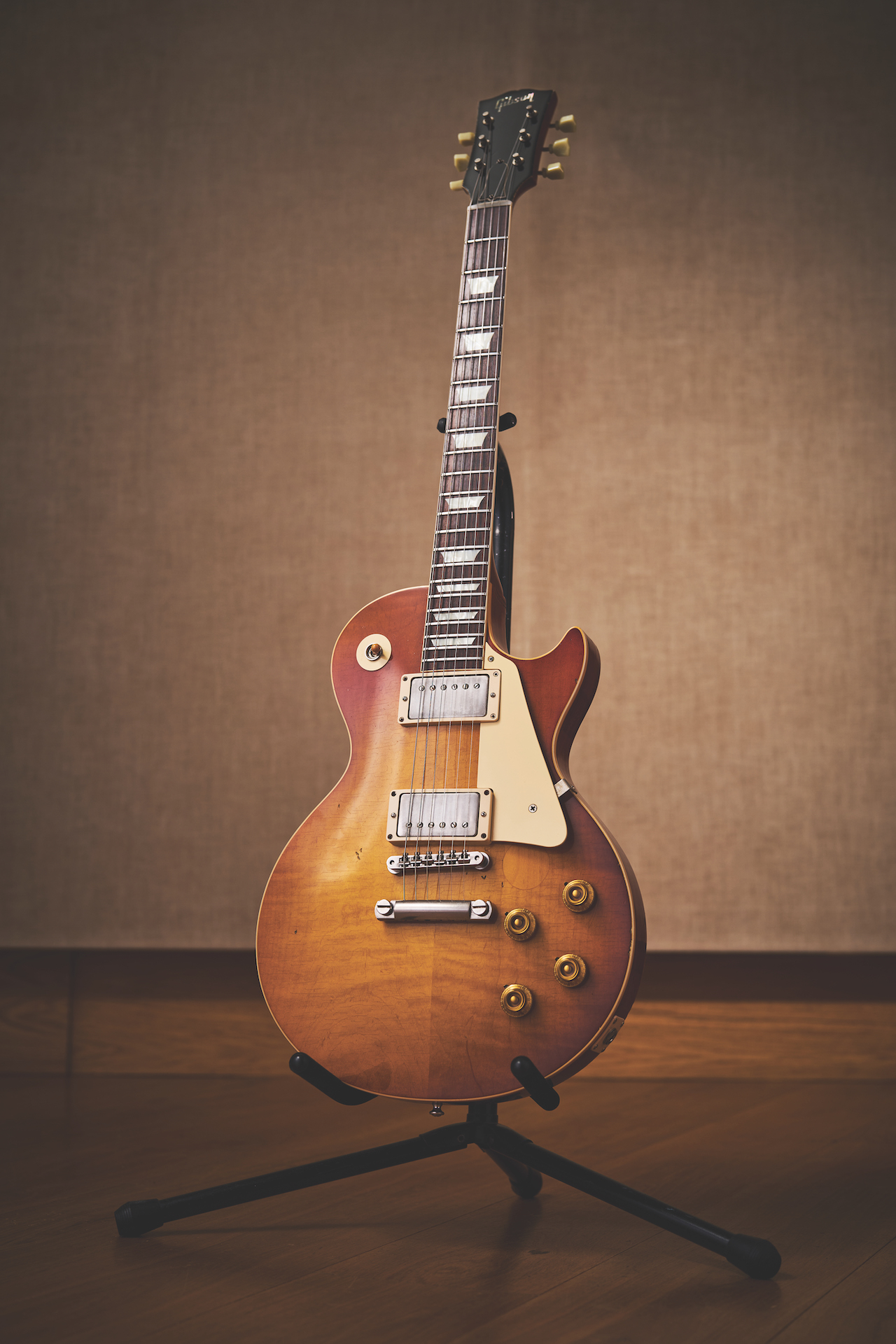

There was his January guitar auction, a somewhat shocking sale of 123 instruments through Christie’s that netted more than $11 million, including $100,000-plus for 28 of them, and a record $876,000 for a 1959 Vintage Gibson Les Paul Standard with a sunburst finish.

That was followed by a new version of his 1983 film composition Going Home: Theme of the Local Hero, which Knopfler and longtime wingman Guy Fletcher turned into a benefit single for Teenager Cancer Trust in the U.K. and Teen Cancer America, using a who’s-who roster of guitar-playing mates and other all-stars, including what is thought to be the final recording by the late Jeff Beck.

But the star attraction is One Deep River, Knopfler’s 10th solo album and first in six years. It’s the product of a prolific time. The 12-song core set is complemented by four bonus tracks on the vinyl LP and a different five cuts on the CD. The sessions spawned another EP of four songs, unified thematically by lyrics about British showground boxing culture of yore.

“Maybe it’s pandemic-based,” says Knopfler, who on top of everything else also launched a syndicated TV show, Johnson and Knopfler’s Music Legends, with AC/DC frontman and fellow northern Englishman Brian Johnson. “Throughout COVID, I was just listening to songs all the time,” he explains. “There was a lot to work with, once we could get back to working.”

He already had quite a history to add to, of course. In addition to Dire Straits’ somewhat limited output (just six studio albums in their nearly 19 years together), Knopfler has cooked up those solo albums – starting with Golden Heart after Straits broke up – and nine film scores, including music for the movies Local Hero, Cal, and Comfort and Joy, all three of which predate Dire Straits’ 1985 breakthrough, Brothers in Arms.

He’s also released albums with the all-star Notting Hillbillies (Missing... Presumed Having a Good Time), his hero Chet Atkins (Neck and Neck), and a pair with Emmylou Harris (All the Roadrunning and Real Live Roadrunning).

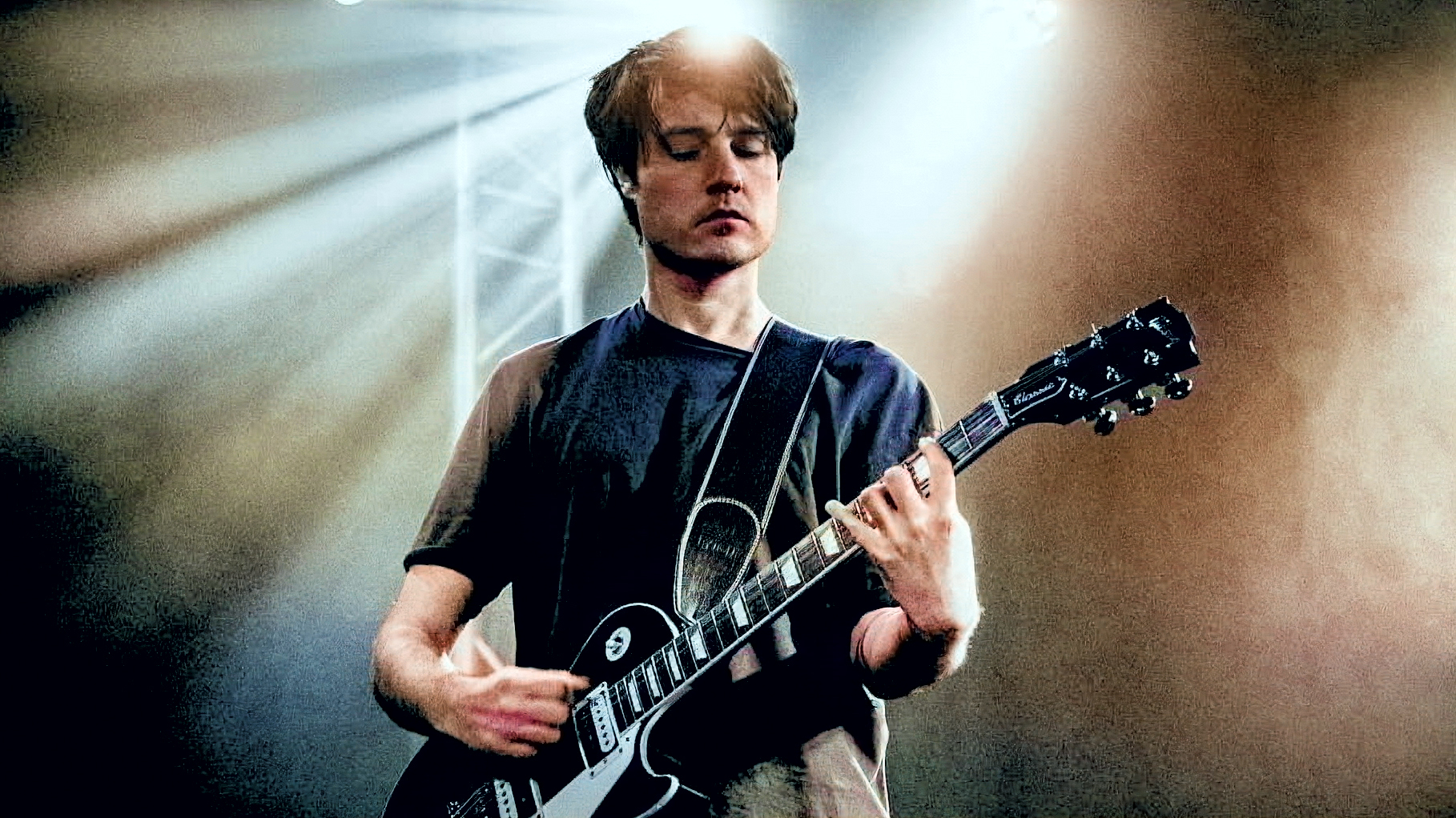

Along the way, Knopfler modestly claims, his guitar virtuosity has taken a backseat to his songwriting talents.

“I see myself much more as a songwriter these days,” explains the man who’s turned the “twiddly bits” from the closing solo of Sultans of Swing into one of rock’s most iconic riffs. “I just became a songwriter, somehow, and a half-baked guitar player. I had to come to see myself as a guitar player in the first place, and music has a way of reminding you that you’re nowhere. And that hasn’t changed.”

The Knopfler-philes among us may be rolling our eyes. But rest assured, he’s just getting started.

“If anything, my grip on the guitar has gotten even worse,” he continues. “The songwriting – it takes you away from concentrating on playing, and it accentuates the simplicity of a lot of my stuff that I want out of the guitar. I’ve almost become a sort of a half-player in the sense that I only tend to play half the notes that are there that I could play, and my fingering is all wrong. I don’t hold the neck properly; I hold the neck like a plumber holds a hammer, not in a proper, artistic way.

I want to bow to the plectrum and say it’s a superior thing. It’s louder. It’s faster. It’s got a better signal. It’s the best amplifier there is

“I think a guitar teacher would say, ‘You’re doing it bloody wrong! It’s all bloody wrong – but it’s too far gone to change it now, so you might as well just do it that way.’ I’m kind of one step ahead of the cowboy chords, perhaps. But not much.”

So it’s kind of like my golf swing?, I suggest. “Well, that’s it!” Knopfler says with a laugh. “But it gets you around the course, doesn’t it?”

What Knopfler has most certainly become is an ardent, although not exclusive, fingerpicker, a skill he developed early on that has become his preferred playing style.

“I started using more and more fingerpicking and less and less plectruming,” he acknowledges. “I think lack of use, plus three bouts of COVID, probably phased out the plectrum for me. I just kept losing them and would be fingerpicking more – not necessarily fingerpicking better, just more. And it proved to be just a bit more comfortable for me.”

Nevertheless, Knopfler doesn’t want his picks to feel like they’ve been abandoned like undesired puppies.

“I want to bow to the plectrum and say it’s a superior thing,” he explains. “It’s louder. It’s faster. It’s got a better signal. It’s the best amplifier there is. I didn’t give it up until recently. I was capable of playing things with a plectrum quite a lot, and I would do all the rhythm parts with one all the time.

“Occasionally I would do a sort of Hank imitation,” he adds, referencing his childhood hero, Hank Marvin of The Shadows. “If I wanted a part where I would need to have a plectrum and play a note, I’d use the whammy bar on the note rather than the vibrato coming from my left hand.”

It should be noted here that Knopfler is actually left-handed but was instructed to play guitar right-handed by his sister, who adjusted the tennis racket he would “play” as a youth. “I had to learn to keep that left hand still on the note and let the whammy bar or the tremolo arm give me the vibrato,” he explains. “And, thankfully, that was something I could feel okay with.

“Hank does that beautifully,” he adds, “but I’m sure he could play the guitar any way that he wanted to. I’m sure he could play flamenco if he wanted to. He’s a really, really good guitar player. So occasionally if I want to have that effect, I can do it. I think there’s a little bit on One Deep River here and there. Maybe Tunnel 13 has a little of that on the Strat, back there somewhere.”

Knopfler recorded One Deep River with a familiar crew, most of whom were part of 2018’s Down the Road Wherever and some albums that go back even further. Producer Guy Fletcher is joined by Jim Cox on keyboards, Richard Bennett on guitar, Glenn Worf on bass, Ian Thomas on drums, Danny Cummings on percussion, Mike McGoldrick on whistles and pipes, and John McCusker on fiddle.

In addition, celebrated pedal and lap-steel player Greg Leisz (his lengthy résumé includes work with Eric Clapton, Jackson Browne, Beck, and John Mayer) is onboard, along with sisters Emma and Tamsin Topolski, who provide the album’s backing vocals.

“I’ve been wanting to play with Greg for a long time,” Knopfler says, “and he fitted in as though he’d been there for 25 years. He got on with all of us just beautifully and behaved as though he was totally a member of the band. He just assumed it and loved it and was part of it, and it was as if everything had been made for him.”

And even though the ensemble hadn’t been able to convene for a while due to the pandemic, once everyone returned to the studio, Knopfler – who does most of his writing away from that environment – says it was just like riding the proverbial bicycle.

“Everybody just played so great, and I think the band has developed a little bit more,” he says. “Playing music together for as long as we have, we now have a better vibe. Danny on percussion works great with Ian on drums, and that improves both of them. When they play together, it just helps the feel, big time. There’s a lot of the intangible, little things, but that’s just part of the joy of the whole thing.”

In addition, Knopfler says, the troupe’s recording methodology has become a kind of shorthand for the musicians.

“I just sing the song to the band with an acoustic guitar, and while I’m singing it the first time, Glenn, who’s one of the resident geniuses, will just write a chart. He might ask me to clarify a few things at the end of it, but pretty quickly everybody who uses a chart has one, and we’re in business.”

And when that happens, Knopfler, explains, “I could have a song before I know where I am, because this group of people play with each other so well. It’s uncanny sometimes: You’d be amazed at how many times our first take has those things that you just don’t want to do without.”

Knopfler gives full props to Fletcher, who joined Dire Straits in 1984, for “keeping tabs on what we’re doing” and being another hand on the wheel. But he acknowledges, too, that the ease and speed of the creativity has advantages.

People bring you instruments and introduce you to them, and you hear other things or see them in a store and try them out. It’s a long education...that’s still going, really

“I did get the opportunity to not be over-familiar with the stuff,” Knopfler says. “We could always move to something else, and everything felt right and nothing felt forced. Everything felt relaxed. If the band wants to play anything ferociously, it can. We just follow whatever way it’s starting to go and feels right. There’s nothing I wanted to inject into it to make things happen.

“It’s an otherworldly kind of band. You can just let the song happen and possibly take credit for it at the same time – which,” he adds slyly, “is a pretty clever trick, if you can do it.”

Part of the Knopfler alchemy, meanwhile, is the casting of specific guitars to particular songs, an act he approaches as carefully as a film director hiring actors. “You’re looking for characters for the songs,” he explains. “You’re looking for a voice for the song. They all have different voices.”

Suffice to say he’s come a long way from the £50 Hofner Super Solid purchased for him when he was an adolescent by his father, an architect and chess aficionado who fled his native Hungary after the Nazi occupation in 1939.

He remembers just one formal lesson, in fingerpicking, from Joe Davidson, the boyfriend of a friend’s older sister. But Knopfler became a connoisseur well before he could afford to become a collector, noting what his favorite players used and making a mental wish list for future purchases.

“Thankfully, success meant that I could go and buy a couple of them. That wasn’t for a long time,” he says, “but you learn as you go along and branch off here and there. People bring you instruments and introduce you to them, and you hear other things or see them in a store and try them out. It’s a long education...that’s still going, really.”

Get him started, and Knopfler will wax rhapsodic about guitars he’s known and loved.

“They’re characters,” he says, returning to the theme, “and there will be a song that answers for them. When you’re onstage you might use something different, but when you record, that’s when you find the right guitar to play for every song you have.”

When it came to making One Deep River, he found an opportunity to give some of them one final dive into the mix before being put up in Christie’s' January auction. Like any six-string acolyte, he speaks of them reverently, as if describing children, and it’s best to just sit back and surrender to his discourse.

“I always try a number of acoustics, and on this particular album the acoustic that burst through was actually the latest one, this Boswell 0-14, a little 14-fret parlor guitar made out of mahogany by Arthur Boswell, who used to work as Rudy Pensa’s repairman in New York City. He graduated from being a repairman to being a builder and set up a workshop in Bend, Oregon.

“Rudy said to me, ‘Marcus, I have this guitar. You have to have one.’ So this little mahogany arrived, and of course I put it to work on the album and it won the audition for a whole pile of songs – at least four or five straightaway. And it’s on more songs on the album itself. It’s on Ahead of the Game, it’s on Tunnel 13, it’s on Sweeter Than the Rain, Before My Train Comes, This One’s Not Going to End Well… That’s half a dozen songs, straightaway, and there were more.

I’m spoiled for choice on Les Pauls, which strikes me as quite ironic, because I had to wait so long before I could get my hands on a good Les Paul

“I also want to mention a beautiful acoustic guitar called a Pete Turner Marrakesh, which is a resonator guitar that Glenn put in front of me. I don’t know how it arrived, but it’s an absolutely beautiful guitar where there’s a lot of thought and work gone into the sound of the body. It’s not just any old body attached to a resonator; there’s a lot of thought in the materials, and the woods are obviously tremendous, and even the resonator has got some serious work on it. I love the guitar.

“[Turner] is very quiet and doesn’t push himself – he hasn’t asked for an advert or anything like that. Usually the great guitar makers, like the Boswells and Turners, don’t push hard. They probably don’t have to; there’s tremendous integrity. So look it up, guys. It comes strongly recommended – by me.

“For the electrics, in a couple cases on the album it’s been a Duesenberg. And actually, Fender made a beautiful replica of the ’54 Stratocaster. I have a ’54 Stratocaster anyway, which also got onto the album, but a couple of times I used the 50th anniversary model, which is really a usable, beautiful guitar and they really took a lot of care making it. It has literally got the porcelain pickups, just like the old ’54s, so you can see they really took care with them.

“There’s one that I play quite a lot which has got a serial number of zero, and that is a great, great Strat. And there’s another one that I’ve had fitted with Callahan pickups, and I used that on a few songs.

“It’s the same thing with the replica Les Pauls they made from my ’58. I think they may have made 58 of them. They all passed through my hands, and they were fantastic guitars. They’ve even got the scratches from my belt on the back of the bodies. I’m spoiled for choice on Les Pauls, which strikes me as quite ironic, because I had to wait so long before I could get my hands on a good Les Paul.

“There’s also a Gretsch 6120 that’s used on a couple of songs. I’ve found from working with Richard Bennett over the years that the DynaSonic pickups ended in ’57, so for me that’s when the 6120 ended. [laughs] Now Chet says he liked the Filter’Trons and he never did like the DynaSonics. Well, I’m the opposite.

“I really like the DynaSonics, because of the sound. The Shadows actually used a 6120 – a lot of people don’t know that – but they got a great sound with an early 6120 with the DynaSonic pickups, and you can’t tell the difference between that and the Stratocaster. Everybody thought it would be a Strat, and they probably still do today. But in fact a 6120 got on quite a few early Shads tracks.

“My almost favorite electric guitar turns out to have been, of all things, a blond [Gibson] 330, which [American singer-songwriter and guitarist] Tony Joe White gave to me when we became good friends.

“I’d given Tony an acoustic guitar made by my old friend Steve Phillips. We were playing one day at Tony’s and he just said, ‘Hey, you can have that guitar. It’s under the bed. Take it out and take a look and see if you want to play it.’ That was the guitar he used on everything: Rainy Night in Georgia, Groupie Girl, Polk Salad Annie... I took it out and it was covered with dust, and the fingerboard had dips and crevices from Tony’s sweaty gigs. But Tony hadn’t played the 330 for years, so I took it to Nashville and had a beautiful new fingerboard put on it and I’ve used it on every record.

I must admit, there were a couple of things that made me gulp a little bit and wish that I was taking them home with me

“And then, obviously, there are the Pensas.”

Knopfler was first turned on to Rudy Pensa’s namesake brand in 2012 via the 2011 custom Blue Ice Metallic MK-D that remains part of his arsenal. He’s added other models since then.

“I’d actually dig out a couple of the Pensas – the old black one to do the screaming, prehistoric sounds. I would use the ’58 Les Paul for that too.

“I’m also lucky enough to own a D’Angelico Excel from the ’30s, which has such a distinctive and beautiful sound. I’m hoping that my Monteleone Isabella” – the custom 2008 model that remains in his collection – “might one day sound like that. You can play anything on that Excel.

“If I’m playing cowboy chords, they sound great, and it’s just because of the guitar, not the player. You can fingerpick it and it just sounds magnificent. I think those Excels from about ’36 or ’37, are just fantastic – as good a guitar as you’re ever gonna find. They’re just ridiculously good.

“You know,” he adds, “Chet told me, ‘A guitar’s your friend for life. It’ll be your best friend.’ And they are. They’re wonderful companions.”

After sitting through a soliloquy like that, you of course have to wonder how the hell Knopfler was ever willing to part with any of his guitars, much less more than 10 dozen via auction.

“I must admit, there were a couple of things that made me gulp a little bit and wish that I was taking them home with me,” he acknowledges. “But at the same time, I’m happy. You can’t just have them gathering dust. It was nice to unload them. It felt good to get them moving and to go on to find other homes and make new friends. And I realized, of course, I’d become a collector, which I never thought of myself as being.”

One instrument that will likely remain with Knopfler for the rest of his days is his 1961 Stratocaster – his first Strat – with which he created Sultans of Swing in 1977, and which has been around his shoulder ever since.

“Yeah, I still have that,” he notes. What would it take to separate him from it? “I’d say a pretty strong guy – or a pretty tough-minded gang of guys. It won’t go easy.”

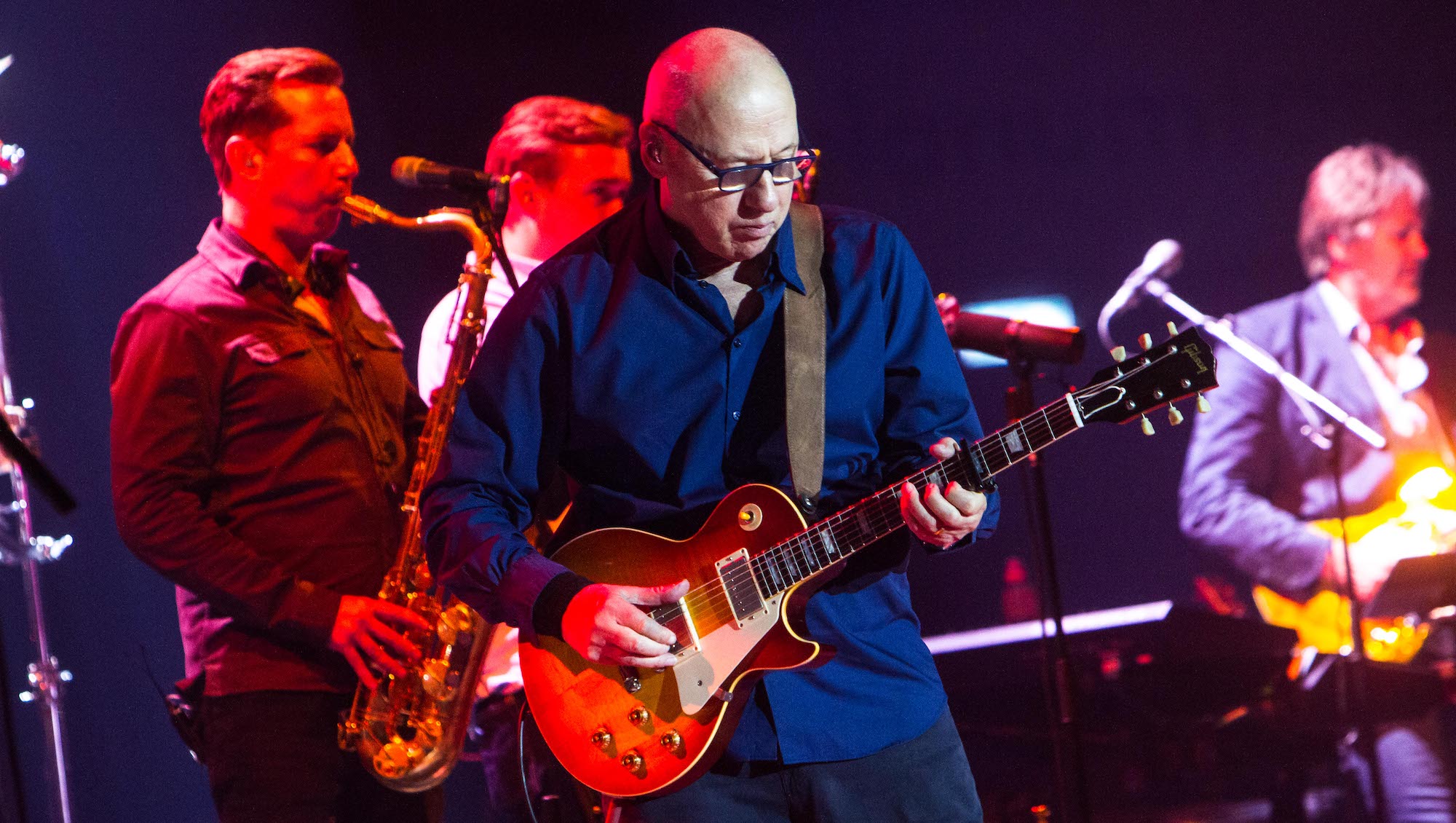

Knopfler describes this year's Coming Home (Theme From Local Hero) charity remake as beautifully chaotic, an embarrassment of riches dumped at his feet – and particularly those of Fletcher, who produced the track.

“It’s a circular moment for me,” he explains, because actually Dire Straits paid for the first Teen Cancer ward at Middlesex Trust about 30 years ago, maybe more. It went from there to University College, where it still is.

“The other day I was up in Newcastle and we launched the song there at the stadium where the Wolverhampton Wanderers play. Then I visited the ward in Newcastle where the kids were, and what a fantastic place! Guitars on the walls. It’s a proper place for youngsters, and such a happy vibe. A young girl in there told me that she was carried into that ward as a baby – she’s a teenager now –and at one point she spent six months in that room, and she walked out. I thought that’s the best thing I’ve heard for ages. It was such a great thing to be there and be told that story.”

The new Going Home has become its own kind of legend. More than 60 musicians contributed to the track, both at British Grove Studios and remotely, and you’d be hard-pressed to figure out who’s missing from a roster that includes Eric Clapton, James Burton, Ry Cooder, Steve Cropper, Duane Eddy, Buddy Guy, Peter Frampton, Tony Iommi, Joan Jett, Alex Lifeson, Phil Manzanera, Steve Lukather, David Gilmour, Brian May, Steve Vai, Joe Satriani… you get the picture. Sting, Sheryl Crow and the Knopfler band’s Worf play bass, with Ringo Starr and his son Zak Starkey on drums and the Who’s Roger Daltrey playing harmonica.

“They just kept coming,” Knopfler says with a chuckle. “It started, quite appropriately enough, with Pete Townshend, because we’ve known Roger [Daltrey]’s association with the charity for so long, and Pete’s as well. It has a lot of input from The Who. So Pete came through the door first at my place, armed with a guitar and an amp, and we plugged it in and Pete played a chord. And we were happening, because when Pete plays a chord, it stays played.

“And then I think Eric Clapton came through the doors the next day, and Jeff Beck had recorded something at his place which was so beautiful. Then David Gilmour came over, and everyone was playing great, and I was really knocked out. I thought, ‘This is fantastic!’ And then all the stuff was coming on from America: Joe Bonamassa, Joe Satriani, Steve Vai... Different people, fantastic guitar playing, coming in from all sides. I came in one day and Bruce Springsteen was all over it.”

Knopfler says the happy glut was the result of organizers who “just didn’t stop. I remember saying to Guy, ‘How are we gonna deal with all this? This is going to be 30 miles long!’”

Knopfler gives full credit to Fletcher for herding everything into a cohesive presentation. “Poor old Guy had to use all his editing skills to get it sorted, but somehow he did it.”

Beck’s part was special for all concerned, of course, because it’s been largely confirmed that it’s the last thing he recorded before his death on January 10, 2023.

“Jeff was just something other, y’know?” Knopfler says. “In fact, we’d just begun some talks, through management, about doing an album together. I’m really sorry we didn’t get to work together.”

Knopfler has received four Grammy Awards during his career, as well as an Ivor Novello Award, a Steiger Award in Germany, and an Edison Award from the Netherlands. He’s also an Officer of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (OBE) at home. He did, however, sit out Dire Straits’ 2018 induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, which left his longtime partner, bassist John Illsley, in the awkward position of both delivering the induction speech and accepting the honor that night – an infamous Rock Hall first.

Knopfler, who never publicly acknowledged the Hall of Fame honor or said he wouldn’t be attending, says he regrets not being there. “Yeah, I guess so,” he admits. In particular, he gets the importance his presence would have meant to his, and the group’s, many fans. “I was a rock and roll teenager, and I spent my whole young life going to see bands. For a lot of years I went to a gig at least every week without fail, so it is a big part of my life.”

Not in the equation anymore, however, is touring. Knopfler and company last hit the road in 2019 to promote Down the Road Wherever, but even with the wealth of new material from One Deep River and its various configurations, he’s not feeling the pull to do it again.

“Touring is for kids,” he says. “It’s for younger people, and stronger people. I’m old enough and I’ve done enough traveling. It’s not fair to the people around me. It’s a great thing to be with family, and the great thing is I can still write songs, and that’s my thing, really, now. I think I’m best off writing the odd ditty, if I can. If I get to make a decent record of it, that’s the objective realized.

“And it’s harder than you think to bring it off. As a writer, I’d like to try and go on working at being successful – not commercially. I’m not bothered about that. Just being a decent writer, that’s all I want. All I’m hoping for is to get a good song written and get it recorded and see if I can make a good record out of it. After all this time, that’s the most important thing.”

Sultans that swing: 3 of Mark’s very finest

1. 2016 Gibson Custom Shop Mark Knopfler ’58 Les Paul Standard prototype

This is the first prototype of the guitar based on Knopfler’s original 1958 ’Burst, which remains in his keeping. It was used to record Janine on One Deep River and to perform Money for Nothing and Going Home on tour in 2019.

2. 2004 Fender Strat

A 1954-spec model made to commemorate the Stratocaster’s then 50th anniversary, this guitar has toured with Knopfler’s sideman Richard Bennett, who played it from 2005 to 2019. Knopfler used this on the tracks Tunnel 13 and Before My Train Comes on the new album, and Bennett played it on This One’s Not Going.

3. Duesenberg Gran Royale

Knopfler’s Duesenberg Gran Royale was delivered to him at a 2019 concert in Berlin at the Mercedes-Benz Arena and was used on One Deep River.

- Mark Knopfler's One Deep River is out now via EMI.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Gary Graff is an award-winning Detroit-based music journalist and author who writes for a variety of print, online and broadcast outlets. He has written and collaborated on books about Alice Cooper, Neil Young, Bob Seger, Bruce Springsteen and Rock 'n' Roll Myths. He's also the founding editor of the award-winning MusicHound Essential Album Guide series and of the new 501 Essential Albums series. Graff is also a co-founder and co-producer of the annual Detroit Music Awards.

“I felt so crestfallen. I wanted to throw my guitar away.” Alex Lifeson on the gig that made Rush feel like they’d made it — and how one audience member brought them crashing down to Earth

“It’s tongue in cheek!" The story of The Beatles song with three guitarists, three bassists, McCartney on drums — and a lyric that made enemies