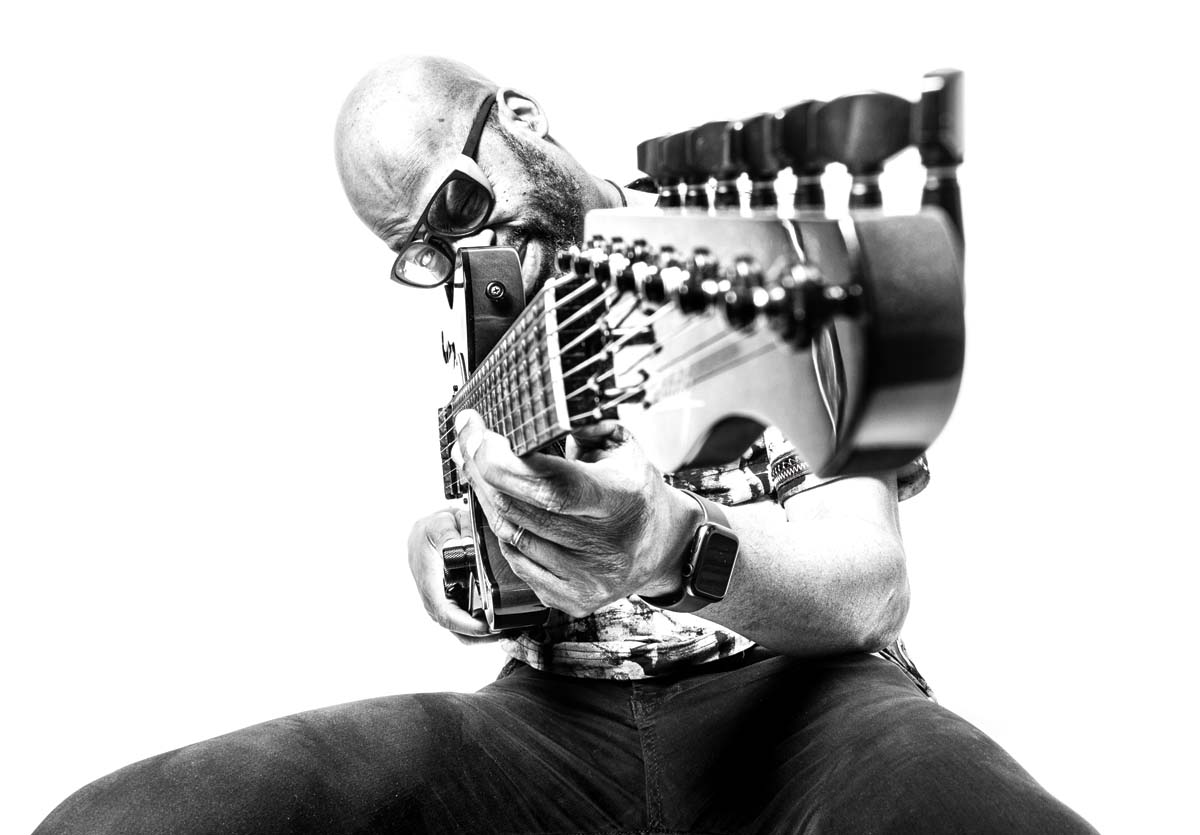

Lionel Loueke Talks Seven-String Jazz Guitar, Rearranging Herbie Hancock, and the Improvisational Magic of a First Take

The jazz fingerstylist gives a musical fist bump to his mentor Herbie Hancock on 'HH.'

After touring and recording with jazz legend Herbie Hancock for the past 16 years, guitarist Lionel Loueke pays a singular tribute to his mentor on HH, his second album for the British label Edition Records and 14th as a leader overall.

An intimate and revealing solo showcase, performed primarily on his seven-string Heeres Geneva Nylon Jazz acoustic, HH finds the gifted guitarist delivering heartfelt interpretations of Hancock classics like “Speak Like a Child” (the title track of Hancock’s 1968 Blue Note album), “Butterfly” (from 1974’s Thrust), and “Dolphin Dance” (1966’s Maiden Voyage), while radically re-imagining “Watermelon Man” (1962’s Takin’ Off and 1973’s Head Hunters), “Cantaloupe Island” (1964’s Empyrean Island), “Actual Proof” (Thrust), and “Rockit” (1983’s Future Shock) with his signature fingerstyle approach to the instrument and inherent polyrhythmic sensibility.

On “Actual Proof,” Loueke weaves an object between the strings for a decidedly percussive effect. And on an experimental version of “One Finger Snap,” he pushes the sonic envelope with myriad of built-in effects from his Kemper Profiler. Aside from his remarkable fingerstyle approach on display throughout HH, Loueke incorporates wordless vocals and Xhosa click-singing (from South Africa) into his arsenal for a more personal touch.

As he explained, “The challenge was to put my own imprint on these masterpieces, to rethink them with my touch on it.”

Born in the West African country of Benin, Loueke took up guitar at age 17 and soon came under the sway of such jazz guitar greats as George Benson, Kenny Burrell, and Joe Pass. After studying music theory in the Ivory Coast, he moved to Paris in 1994 and studied jazz harmony for three years at the American School of Modern Music.

The challenge was to put my own imprint on these masterpieces, to rethink them with my touch on it

It was during this period that he first encountered the music of such jazz guitar modernists as Pat Metheny, John Scofield, and John Abercrombie.

In 1999, Loueke began a two-year scholarship to the Berklee College of Music, where he studied with guitarist Mick Goodrick and also met and began playing with Swiss-born acoustic bassist Massimo Biolcati and Hungarian drummer Ferenc Nemeth.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Together, the three relocated to Los Angeles in 2001 to attend the Thelonious Monk Institute, where they continued to study and further develop over the next two years, subsequently forming their highly interactive trio, Gilfema.

Their remarkable chemistry can be heard on the trio’s self-titled debut from 2004 and its 2008 followup, Gilfema + 2, both on the ObliqSound label, and also on 2020’s Three for the Sounderscore label. Loueke debuted as a leader with 2004’s Incantation, followed by two other independent releases in 2005, Afrizona and In a Trance, and 2006’s Virgin Forest for Obliqsound.

His Blue Note Records debut, 2008’s Karibu (featuring Hancock and Wayne Shorter), was followed by a string of impressive releases for the label in 2010’s Mwaliko, 2012’s Heritage, and 2015’s Gaia.

After relocating to New York City in May 2003, Loueke quickly became an in-demand player on the Big Apple scene, appearing in bands led by trumpeter Terence Blanchard, trumpeter Avishai Cohen, drummer Jeff “Tain” Watts, and pianist Robert Glasper.

He toured and recorded with Blanchard, appearing on 2003’s Bounce and 2005’s Flow, before joining Hancock’s touring group. In 2017, Loueke toured internationally with the Chick Corea/Steve Gadd Band as a followup to the release of their album, Chinese Butterfly.

Loueke relocated to Luxembourg in 2017 and goes back and forth one week per month to Switzerland, where he currently teaches at the Musik Akademie Basel jazz camp.

This is a beautiful, heartfelt tribute to Herbie Hancock. How did you meet him?

When I came to Los Angeles in 2001 to audition at the Thelonious Monk Institute, he was one of the judges, along with Terrence Blanchard and Wayne Shorter. So I met all of them together that same day. After I finished the audition, Herbie said, “Well, what about we just forget about the program and I take this guy on the road?” And everybody in the room laughed.

The director of the Monk Institute, Tom Carter, was saying, “No, no, he has to finish the schooling.” You know, I wanted to go to this school to study and learn. But then, of course, as a young player, if the opportunity will come, I will do it. But my first thinking was to just stay in school, and I did for two years.

Terrence Blanchard was the musical director of the program and I ended up playing with him, mostly during the weekend, which was the only period where I could travel. And then when I finished the two-year program, Herbie asked me to play with him. Of course I was honored, but he mentioned that the band was going to be just a quartet, and I wasn’t sure how guitar and piano would fit together in a small setting.

But he said, “It’s not just about guitar; I like what you do. You play percussion on the guitar, you’re singing, so I think it’s going to be cool.” So he had a vision of what he was hearing and how I would fit into it. The first gig he asked me for was in Italy, and it went well. And I’ve been playing with him ever since.

Great pianists like Herbie and Chick, they listen closely to you and make suggestions, give you nice ideas to respond to so that you can do your thing the best way possible

Because you comp so pianistically on the guitar, did you have to learn how to mesh with Herbie’s piano playing?

That came very natural, though I’m still learning a lot, actually. I played with Herbie for so many years and a lot of other piano players since then, most recently Chick Corea. I guess my thing has been to find my way to whatever situation I’m in. And it’s about really paying attention to all the elements going on around you and picking your spaces.

Great pianists like Herbie and Chick, they listen closely to you and make suggestions, give you nice ideas to respond to so that you can do your thing the best way possible. But the way I see it, it has to be a healthy back and forth. As much space as they give you, you give them space and find a way to play together.

With Herbie, it has been especially good because he doesn’t stick strictly to the chart. It might say Cmaj7, but he might decide to go somewhere else in the moment and you have to respond to that. He might not land on that Cmaj7 even though that is what is written on the chart. So I have to use my ears and make quick decisions based on whatever’s coming to me.

You take some liberties yourself with Herbie’s compositions on HH.

Oh, yeah. Otherwise, I wouldn’t have done it. We all know the originals were powerful and beautiful, so my idea was not to make anything better or worse, just to present something different.

I wanted to use my approach to those beautiful tunes that I played many times with Herbie and make them my own. So you can recognize them with the melody, but actually on most of them I did change the rhythm. Like on “Butterfly,” I go back and forth between a West African 6/8 and 4/4.

And on “Actual Proof” I think I’m playing 13/8. They’re all different meters. “Cantaloupe Island” is one that is close to the original in terms of time signature. There is some reharmonization on that one but not that much compared to the original.

I didn’t want to think too much or make huge arrangements of pieces. Even when I overdubbed on a few tunes, I would say 80 percent was completely improvisational, and I always used the first take

Your version of “Hang Up Your Hang Ups” [from 1975’s Man-Child] is a pretty straightforward reading.

Yeah, it’s the same kind of groove or tempo of the original. But there’s also some new sections, different things that just happened in the studio that I didn’t really plan. And if I liked it, I just kept it. But, in general, I really tried to keep the very organic part of my playing on the record, so I didn’t want to think too much or make huge arrangements of pieces. Even when I overdubbed on a few tunes, I would say 80 percent was completely improvisational, and I always used the first take.

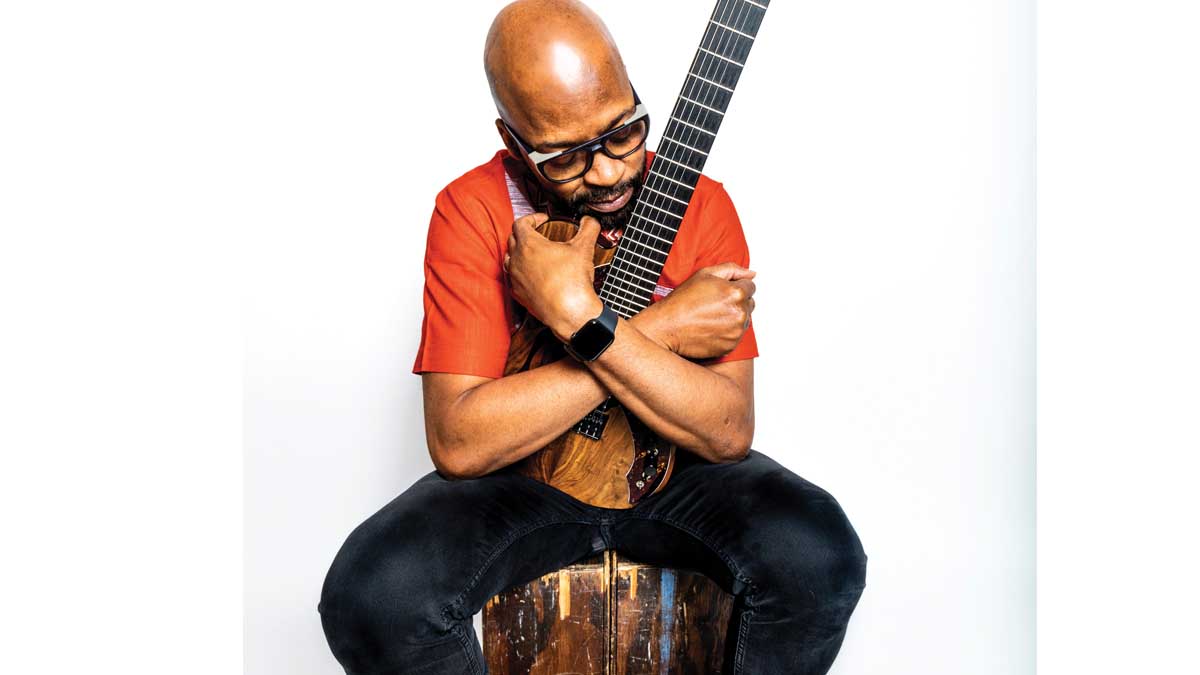

It’s primarily a solo acoustic recording in real time, performed on your beautiful-sounding seven-string made for you by luthier Richard Heeres. But there are a couple of exceptions on the record where you do play electric.

Yes. For “Rockit” I got out my Stefan Schottmueller electric guitar and played that with some effects. And I also used the Schottmueller on “Cantaloupe Island” with some light wah-wah effects and dialing up the AC30 amp modeling on my Kemper amp.

Was playing in such a revealing solo setting a daunting task for you?

That was the challenge, knowing that there’s no other musician around to rely on. So I pushed myself to the limit. And it’s by trying that you discover, so I wasn’t afraid to just go for it and see what I get. And if I don’t like it, I’ll do it again in another direction. And that’s what I did throughout the whole album.

For example, Massimo Biolcati, who was co-producing, suggested at the session that I play “One Finger Snap.” I wasn’t thinking to record that tune, but we had time so I said, “Why not?” So I just went for it. What you hear on the record was the first take. I didn’t even try to change it. I was like, “Okay, that’s what it’s going to be.”

Because I know myself that when I have to re-do anything, I start thinking too much and I start losing the essence. The original part of my playing starts disappearing because I’m thinking and trying to make it better. So either for my own music or for anybody else I’m recording with, the first take is the best for me, because otherwise I’m thinking too much.

I know myself that when I have to re-do anything, I start thinking too much and I start losing the essence

Can you describe what’s going on sonically with “One Finger Snap.” It sounds like a heavily distorted electric guitar or MIDI guitar.

That was my acoustic seven-string. And because the guitar has a piezo pickup, I connected it to my Kemper amp, which has built-in effects and amp modeling and a pedalboard.

So I was playing through the Kemper, and then I had a few mics for the guitar as well. So if you listen carefully, the loop is going straight to the amp, and the mics are capturing whatever I’m doing live. So you can hear the volume and quality of the loop is slightly different from the guitar.

And the effects are all crazy stuff – ring modulators, wah-wah, and a whammy pedal for dividing a note into three different octaves: higher, lower, and middle. And it’s got a kind of ping-pong delay, but with a variation of octaves. Those are the main effects that I use. And I have a remote controller on the floor to control basically the head amp. So every effect is coming from the same unit.

You approach “Come Running to Me” [from 1978’s Sunlight], which was originally a kind of Fender Rhodes–vocoder vehicle for Herbie, as a tender bossa nova – more João Gilberto than Herbie Hancock.

I guess my focus on “Come Running to Me” was actually the lyrics, the voice, because I wanted to sing that tune in fon [the language of Loueke’s homeland]. But using Herbie’s words and finding the right interpretation in fon was challenging. So I guess the solo acoustic guitar and voice can definitely remind one of the Brazilian vibe.

I just decided to move on to seven-string to make it easier to cover both bases, and I’m pretty happy for what I’m getting, because it kind of extends the range of the instrument the way I want it

What about making the transition from six-string to seven-string? And why did you chose low B instead of low A, as most seven-string jazz players use?

I’ve played seven-string now for the last four, five years, so that’s my main thing now. As to why I switched, I was a bass player from the beginning and I kind of missed that.

When I was playing with six strings, I used to do many trio gigs without a bass player, whether it was with [drummer] Jeff Ballard’s group or [alto saxophonist] Miguel Zenon’s group. And I always ended up covering bass lines in those trios, so I had my foot in those two places – guitar and bass.

Eventually, I just decided to move on to seven-string to make it easier to cover both bases, and I’m pretty happy for what I’m getting, because it kind of extends the range of the instrument the way I want it. And I went low B because low A, to me, is a little bit too much in the bass territory.

What’s going on with “Voyage Maiden”? That’s an interesting reimagining.

Obviously, it’s inspired by Herbie’s classic tune, “Maiden Voyage.” I can’t remember what time signature I was playing on it, but I think it was 9/8 or 11/8. I started off trying to reharmonize “Maiden Voyage,” basically just messing around, and I kind of liked the harmony I was creating.

So I said, “You know what? Let me write this new harmony.” And from there I played around with the notes on top of the voice leading. So basically, it’s a new tune that has “Maiden Voyage” as a reference.

All those odd meters, I really tried to make them sound natural. The idea for me is not to be counting, or for the listeners to be counting. Just listen to the music

Your approach to “Tell Me a Bedtime Story” reminded me of Joe Pass.

He was one of the kings of playing solo guitar and definitely an early inspiration. When I’m playing solo, I try not to have just chords and notes; I’m trying to have some polyrhythmic relation between the bass and the harmony, divide them in different ways.

This version was in a different meter from the original; I think it was in 11/8. But again, all those odd meters, I really tried to make them sound natural. The idea for me is not to be counting, or for the listeners to be counting. Just listen to the music.

You’ve developed such an intuitive fingerstyle approach. Did you ever play with a pick?

Oh, yes, when I went to the Berklee College of Music. And then when I went to the Monk Institute, the first year I was using the pick, but then the second year I began questioning that. With a pick I wasn’t able to do all the stuff I was hearing, in terms of trying hard to separate those voicings.

I was hearing a lot of different things, rhythmically speaking, that I couldn’t really get to with the pick. So I decided to take some classical guitar lessons, and I found a teacher in Los Angeles at USC, and I start taking classical guitar lessons just for the right-hand technique.

Playing without a pick allows me to be more polyrhythmic with my right hand

That was around the time I was playing with Terence Blanchard. So it was frustrating at the beginning, because I would go to the gig and keep my pick on top of my amp, in case I needed it. I remember a gig we were playing at a club in D.C. I played half the gig with a pick and half without it.

But right after that, I put the pick in my wallet, and from that day to this day I never used a pick again. And I don’t miss it, because I find a way to do whatever I was doing with the pick now. Playing without a pick allows me to be more polyrhythmic with my right hand.

The idea for me was, again, to get a better approach to the piano – to find a way to, harmonically speaking, get to the piano and how piano players improvise. I know piano players have 10 fingers completely independent. With guitar, we are limited a little bit. But I’m trying to find a way to get closer to the piano without having that many fingers free.

Bill Milkowski's first piece for Guitar Player was a profile on fellow Milwaukee native Daryl Stuermer, which appeared in the September 1976 issue. Over the decades he contributed numerous pieces to GP while also freelancing for various other music magazines. Bill is the author of biographies on Jaco Pastorius, Pat Martino, Keith Richards and Michael Brecker. He received the Jazz Journalist Association's Lifetime Achievement Award in 2011 and was a 2015 recipient of the Montreal Jazz Festival's Bruce Lundvall Award presented to a non-musician who has made an impact on the world of jazz or contributed to its development through their work in the performing arts, the recording industry or the media.