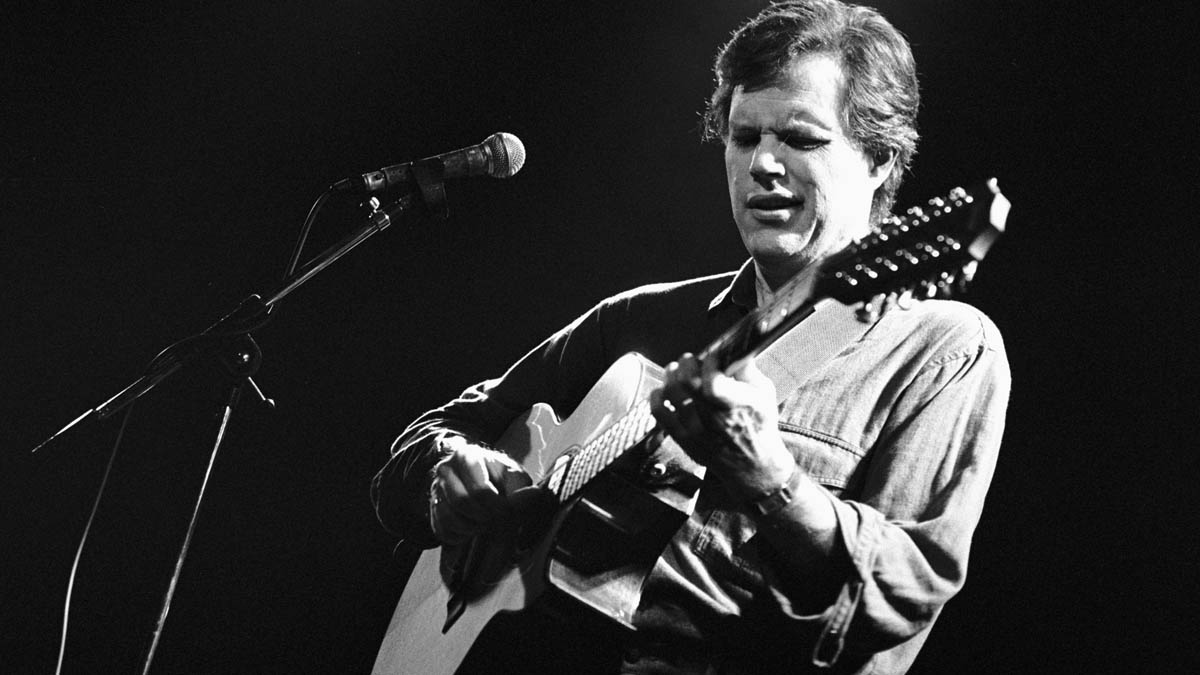

Leo Kottke Talks 12-Strings, His Fingerpicking Evolution, and What Makes a Good Guitar Player

The GP Hall of Famer unpacks his technique and guitar philosophy.

Last month, in the first part of our Frets feature with fabled fingerpicker Leo Kottke, he detailed the making of his fantastic duo redux with Phish bassist Mike Gordon, Noon (ATO).

In this issue’s second and final installment, Kottke offers a profound examination of his singular stylistic evolution, seen largely through the wide-angle lens of the 12-string. The GP Hall of Famer’s impact is comparable to an unplugged Hendrix in that Kottke set the tone for the modern acoustic guitar hero.

When aficionados discuss elite players, Kottke’s name always comes up, as it did when GP delved deeply into the subject for the August 2017 acoustic special issue. Cover artist Tommy Emmanuel said, “I remember when GP had a poll about a dozen years back for the readers’ favorite acoustic albums of all time. Of course, Leo Kottke’s 6- and 12-String Guitar came in at number one.”

I’ve spent most of my time sitting in a room playing guitar, and I’m still doing that

Kottke graced the cover of Guitar Player exactly 40 years prior for the August 1977 cover, and he was also a Frets cover artist multiple times back when it was a standalone acoustic magazine.

Kottke’s very first release was 1969’s 12-String Blues, and the noteworthy evolution of his idiosyncratic fingerpicking style is better understood when scrutinized via the 12-string filter.

He explained that the 12-string didn’t make an appearance on Noon due to the nature of his duo with Gordon on bass. But, as he elucidated, the instrument played a starring role in the script of his life, even if it remains something of an enigma to the maestro, who wields his own signature Taylor 12.

When did you realize that you were all-in as a guitar player?

The guitar came and got me when I was a boy. It’s possible to be musically developed and not be playing the instrument you’re made for. I truly thought I would be a trombone player until the guitar came along. When it hits you, it’s like a drunk taking his first drink, and bells and whistles go off like fireworks.

You don’t worry about a thing after that. You’ve got what you want to do, and nothing else matters. Fortunately, it also became a job for me, because I spent so much time with it that I don’t have any other skills.

It’s all about appetite, I swear. People talk about things like study, talent, and influence, but none of that means anything if you don’t have the appetite. I’ve spent most of my time sitting in a room playing guitar, and I’m still doing that.

Was it the six- or the 12-string that made you starve for more?

I was very sick when I was about 11, and the guitar got me out of bed. It was a very bad six-string. I’d been on my back for two months. I sat up, made an E chord, and within a week the guitar cured me. It had nothing to do with the guitar itself, because it sounded like a deck of cards being shuffled.

The sound came from a 12-string Gibson B-45 I found hanging on a wall in ’62 or ’63. It had 10 feet of finish that I eventually got off there, but I remember taking the 12-string off the wall, and that was it.

For a long time, that 12-string was all I wanted to play. My first job was in [Washington] D.C. I played for free beer, and they charged me for the beer afterward. When I started working around Minneapolis, Wisconsin, and Michigan, all I had was the 12. I needed something to break up the set, and that’s what got me to the six.

Most guitarists have some sense of the six-string’s history. Would you agree the 12-string remains more of a mystery?

Yeah, and it’s in a way impenetrable. Every time I ask somebody who should know, nobody has the facts about how the 12 came up. Now that I think about it, the first 12-string instrument I had briefly might have been a bajo sexto set up as a 12-string guitar.

But the first good one I got was the Gibson, and that was the first time I heard one personally. I’d heard recordings, including Fred Gerlach [famous for “Gallows Pole”], Willie McTell [“Statesboro Blues”], Barbecue Bob [Piedmont blues style], Reverend Gary Davis [check out “Twelve Sticks”], and Pete Seeger’s “Living in the Country” live at the Bitter End [likely 1962’s The Bitter and the Sweet].

I wanted to play that tune. Before then, I didn’t hear anything I wanted to play. That’s why I started making shit up – I wasn’t hearing what I wanted to hear, and I couldn’t play a lot of what I did hear. Pete had that big 12 with the triangular sound hole. It was strung very heavy and had a huge scale length. Pete would capo it way up. It was the sound from all of them that got me.

David Lindley feels the same way. He loves the sound of two strings together. Once you get that bug, you’ll chase it for decades because you cannot otherwise get that quality. Also, I wanted to play solo. I didn’t have any interest in playing with other people because I’d done the single-note thing with the trombone. You can get chords, counterpoint, and patterns going on a guitar.

On the 12-string, the big thing for me was how the octaves on the bass side of the instrument have a way of supporting what you have to do if you’re playing fingerstyle

On the 12-string, the big thing for me was how the octaves on the bass side of the instrument have a way of supporting what you have to do if you’re playing fingerstyle, and that is to turn your thumb into a finger. You don’t want that thumb going blink, blink, blink. That can work well, but I wanted to get something else, and Pete had that a little on “Living in the Country.”

Gerlach had it a little on a couple of his Lead Belly covers – and, of course, there’s another obvious 12-string guy. Lead Belly had a tune called “Grasshoppers in My Pillow” that I remember doing on an audition for some radio show. I sat in a guy’s office and screamed that at him. Back then, that’s all I could do. I didn’t get, you know – broadcast.

It’s interesting to hear how playing a 12-string influenced the way you stick your thumb way out like a hitchhiker to hook the bass strings. And, of course, you had a heavier attack back then using metal fingerpicks. Can you detail the evolution of your fingerstyle?

I saw a picture of Lester Flatt using a thumbpick, so I got a thumbpick. The fingerpicks came along because I saw Earl Scruggs wearing those things out [on banjo]. Lindley uses fingerpicks often enough all together. I thought I was supposed to be doing that, but fingerpicks didn’t work for me, although they do kind of help with some playing on the 12-string.

Before your right hand is fully developed, the fingerpicks seem to give you something for free, and in a way they do. But in the long run, it narrows your perspective and removes you from the strings. I actually play with more authority now than I did with the picks.

I could play hard, but not with authority. And it’s very difficult to play with good dynamics, but I didn’t know any better. I didn’t understand until I started seeing players live. John Jackson, Son House, John Hurt, and Fred McDowell played with their fingers. I remember seeing John Hurt in D.C., where his wife was sitting directly in front of him.

I actually play with more authority now than I did with the picks

He’d smile at her with that two-toothed smile of his and knock her on her ass! She was older than I am now, and she had no ass left, but I could feel their energy all the way in the back of the room. I felt I needed some of that, although I was just a kid and realized that I didn’t want to get that old that fast.

But John really had something. The picks finally got away from me when I discovered real rhythm. There’s velocity, and you can have a ball with velocity – “going down the road,” as Joe Pass told me – but you get the real chunk and feel with your fingers.

It took me until somewhere in the ’80s to get there. I could get rid of the fingerpicks, but I couldn’t handle going without the thumbpick. I’d get so disoriented and weak, but I’d think of the feeling Fred McDowell and Son House had playing with just their fingers and maybe some fingernail in there somewhere.

That’s where I’m at now. I’ve done the nails thing too, but I eventually realized what I’d suspected all along: It is not helpful to have a nail. You just need a little bit to back up the flesh. Otherwise you get a wet sock sort of attack, and you want to have your full dynamic palette available.

Can you talk about how you pluck up and down arpeggios in clusters using multiple digits?

Well, it’s just pigging out, really. I have to rein that in sometimes, because you can lose your contrast if all you do is pig out. I play a lot of double-stops with my right hand, using my middle and ring fingers. That happened because I injured the joint on the middle finger by carrying a heavy case through Germany.

Don’t carry anything with your fingers, especially your heavy guitar case. Always put that handle in the palm of your hand when you lift, because you can injure a tendon, like I did. For a while it felt like my middle finger had its own little condom, so I would back it up with the ring finger, which became a habit.

That’s part of what you’re hearing, and I love to hear combinations up and down the neck, which is part of wanting to get as much piano out of it as I can. It’s also great for rhythm and meter if you can pull some clusters as well as single lines.

Does the cluster technique influence your tendency to work in certain time signatures or incorporate odd measure counts?

The time stuff happens without my knowing it. I do a lot in 12/8, and I often tend to write in 9[/8]. Some of the odd stuff comes about when you need to get from here to there, and you’re not going to make it otherwise. The rhythm will do it for you if you go by feel, sort of like changing gears on a bicycle.

It helps to have a nice ride, such as your signature Taylor. Is that still your main 12-string?

Yes. I have one that’s been on the road with me for a long time, and a couple of backups. Those guitars hold together really well, which turns out to be very important. The signature model came about after I’d bought a Taylor in Florida. The shop owner called Taylor and told them what I’d done to it, which was to take a lot of the bracing out with a pocketknife.

Duke Ellington is credited with having said that there are only two kinds of music – good and bad – and, boy, is that true

That’s pretty brutal shit. I don’t know if I’d have the gall to do that today, but I did it to a lot of 12-strings, because they were all overbraced. I like the braces to be tall, narrow, and thin. Taylor didn’t like hearing that back when they offered to do a signature model. We eventually arrived at a compromise. I don’t play the Taylor because I’m involved with it; I play it because I haven’t found anything I like as well.

You’ve influenced a broad range of guitarists. In this very issue, Steve Stevens credits your playing as the inspiration for the fingerpicked “battle cry” intro to Billy Idol’s “Rebel Yell”

Were you aware of that? No shit? I’ve never heard that, but I’ve heard of Steve Stevens, of course. That’s great. That’s the way it ought to be. Duke Ellington is credited with having said that there are only two kinds of music – good and bad – and, boy, is that true.

Marketing is a necessary part of everything, but it has not been kind to music. There really is no line, no bin, no separation. The better the player, and the more you hear things like that, the more you realize that it just doesn’t exist.

Well, here’s the most important thing: Don’t get thinking that you have to be good. Taking it all too seriously will ruin you

What’s the nicest compliment any player has ever paid you?

Well, here’s the most important thing: Don’t get thinking that you have to be good. Taking it all too seriously will ruin you. Stan Getz is a great example. He could play heartbreakingly beautiful stuff that he seemed to just throw away. There is a great quote from him that says, “You should play everything with irreverence.”

It doesn’t mean you’re clowning. You’re not goofing off. It’s not disrespect. The irreverence is the ultimate respect. The tune does it, not you. Do your job for your well-being. Do it with irreverence.

When you hear somebody play with reverence, it’s kind of embarrassing. Jazz bassist Buell Neidlinger played with everyone from Miles Davis to Cecil Taylor, and he produced a couple of records for me. His lifelong goal had been to get so good that he could cut anyone, anytime, anywhere.

He told me that the minute he got there, it didn’t mean shit. He realized that the true goal isn’t only to be good but only to play what’s good. He said one of the nicest things anyone has ever said to me: “You play the same old shit in a different way.” And I love the same old shit, but I don’t want to hear the same old shit, so he couldn’t have hit a better nerve.

- Leo Kottke and Mike Gordon's Noon is out now via ATO.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Jimmy Leslie has been Frets editor since 2016. See many Guitar Player- and Frets-related videos on his YouTube channel, and learn about his acoustic/electric rock group at spirithustler.com.

“We’d heard Jimi Hendrix, we'd heard the Who, but now we finally got to see these guys. And watching Jimi Hendrix burn his guitar….” Grace Slick on Hendrix at Monterey, Jefferson Airplane and the Spanish origins of “White Rabbit”

“I’m still playing but I’m covered in blood. Billy’s looking at me like, ‘Yeah! That’s punk rock!'” Steve Stevens on his all-time worst gig with Billy Idol — and the visit to Jimi Hendrix's grave that never happened