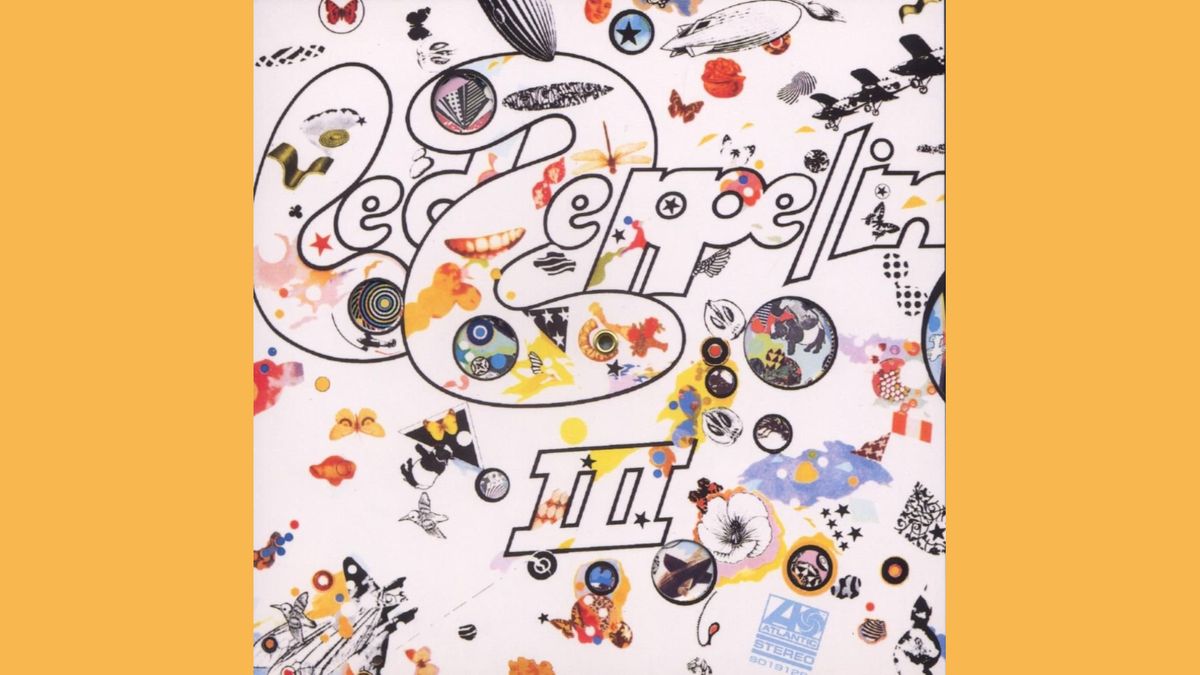

“Our Attitude Was, ‘F**k the ’60s! We’re Going to Chart the New Decade!’” How Led Zeppelin Took the ‘70s By Storm With Their Game-Changing Third Album

As a new decade unfolded, 'Led Zeppelin III' unlocked the musical adventurism that flowed freely throughout the band’s subsequent albums

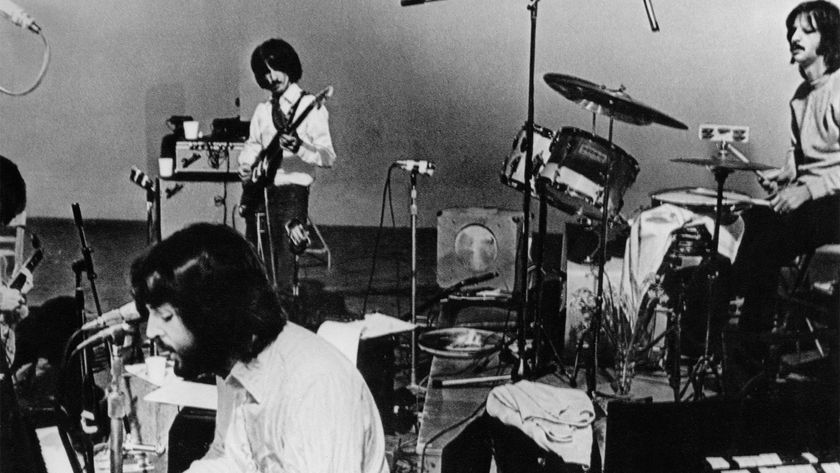

At the dawn of the 1970s, Led Zeppelin were one of the biggest rock bands in the world. Though the foursome of Jimmy Page, Robert Plant, John Paul Jones and John Bonham had been in existence for just upward of a year, in that brief span of time the group had released two massive-selling albums – Led Zeppelin and II – and performed more than 150 live shows across the U.K., Scandinavia, Europe and North America. The U.S., in particular, had embraced the band, perhaps even more than its British homeland, with fans on these shores ravenous for the group’s heavy blues-rock sound.

Of course, Zeppelin were hardly the only British band playing that style in the late 1960s. During that time, Cream, Ten Years After, the Jeff Beck Group, Vanilla Fudge, Iron Butterfly and Page’s previous band, the Yardbirds, among others, had plundered black American blues music in the service of creating something more modern, multifaceted and riff-centric.

But arguably none of these acts did it with the same balance of bombast, agility, songcraft and barely restrained ferocity that Zep achieved in the studio and onstage. As Jimmy Page once remarked of the band’s arrival in America, “It felt like a vacuum, and we’d arrived to fill it. It was like a tornado, and it went rolling across the country.”

Zeppelin’s bombastic style was defined by Page’s “Whole Lotta Love”-style proto-metal riffing, Plant’s histrionic wail and Bonham’s cannon-blast drums. But there was always much more to the Zep sound – the “light and shade,” as Page so often referred to it. And nowhere in the Zeppelin catalog is that approach so clearly on display than on 1970’s Led Zeppelin III.

To be sure, there’s plenty of heavy rock on the album, starting with the thundering opener, “Immigrant Song,” and continuing with “Celebration Day,” the heated minor-blues workout “Since I’ve Been Loving You” and “Out On the Tiles.”

On the other side of the coin is the small clutch of songs that has served to forever define Led Zeppelin III as the band’s “acoustic album.” Those tracks include the folky, pastoral “That’s the Way,” the rustic hoedown “Bron-Y-Aur Stomp,” the traditional reworking of “Gallows Pole” and the Eastern-tinged, alternate-tuned “Friends.”

It’s certainly a fair categorization. Zeppelin never had, nor would again, explore acoustic instrumentation to such an extent. Yet these unplugged elements had been present in the band’s sound practically since the start of their existence.

In fact, the folk-blues “Babe, I’m Gonna Leave You” was among the first songs that Page played for Plant at one of their earliest meetings, in mid-1968, at the guitarist’s houseboat on the River Thames in the village of Pangbourne. The tune was written by a University of California, Berkeley student named Anne Bredon in the 1950s, and was subsequently adapted by folk singer Janet Smith. Joan Baez heard that version and made the song her own.

Page, a dedicated Baez fan, took a liking to the track, although he stated that by the time he played Baez’s version for Plant in Pangbourne, he had already decided upon his own approach to it, “using a more fingerstyle method and then having a flamenco burst in it,” he said. “It’s light and shade, and this drama of accents.”

Led Zeppelin recorded their version of “Babe, I’m Gonna Leave You” for their 1969 debut, complete with a newly composed, full-band instrumental assault in the choruses. That album also included another Page acoustic moment, “Black Mountain Side,” which borrowed heavily from British fingerstylist Bert Jansch’s interpretation of a traditional Gaelic folk tune known as “Down by Blackwaterside.” Jansch was a key figure in the British folk revival of the 1960s, and many of Page’s British guitar peers, Eric Clapton and Keith Richards among them, were avowed fans of his work. But neither Clapton nor Richards were able – or, really, even attempted – to synthesize Jansch’s approach into a rock context.

Zeppelin never had, nor would again, explore acoustic instrumentation to such an extent

Page, on the other hand, incorporated the interlocking, baroque-sounding fingerstyle patterns and alternate tunings of British folk revivalists like Jansch and Davey Graham (whose “She Moved Through the Fair” Page used as the basis for his own instrumental, “White Summer”) to add a unique character to Zeppelin’s sound.

Indeed, the hypnotic acoustic lines, incorporating unusual chord voicings and droning open strings courtesy of DADGAD tuning (which Graham had helped popularize) seemed to function as a portal into an antiquated and esoteric universe that existed far outside the more straightforward riff rock and earthy blues howls of Zeppelin and their peers’ primary source material.

What led Page to be so receptive? Perhaps it was down to his naturally omnivorous tastes. He grew up enamored of everything from blues, rockabilly and skiffle to folk, traditional music and jazz. But there was also his extensive history as a working guitarist in various styles, which led him to label himself an “all-arounder.” Page was only 24 when he left the Yardbirds and formed Led Zeppelin, but by that point he had already made his name as an in-demand session musician, playing, often uncredited, on recordings for artists in a wide range of styles.

“You just got booked into a particular studio at the hours of two and five-thirty,” he explained. “Sometimes it would be somebody you were happy to see, and other times it was, ‘What am I doing here?’” The idea of commiting to just one musical style might have never even crossed his young mind. “There’s such a wealth of arts and styles within the instrument… flamenco, jazz, rock, blues… you name it, it’s there,” Page once said. “In the early days, my dream was to fuse all those styles.”

And so, with Led Zeppelin, he did. But while Led Zeppelin III is commonly viewed as the band’s “acoustic album,” it is also so much more, taking the rock, blues and folk elements present on the band’s first two albums and synthesizing them into something unlike anyone else was making at the time, be it the exotic futurism of “Friends,” the otherworldly “Hats Off to (Roy) Harper,” which twists the Delta blues into an echoing miasma of harsh slide guitars and distorted wails, or the almost jazzy electric blues of “Since I’ve Been Loving You.”

“Led Zeppelin was definitely growing, there’s no doubt about that,” Page has been quoted as saying of the band at this time in its complicated history. “Where many of our contemporaries were narrowing their perspective, we were really being expansive.”

Led Zeppelin was definitely growing, there’s no doubt about that

Jimmy Page

All of which is to say that, when it came time to begin work on their third album, Zeppelin were ready for something different. And so, after completing their fifth North American tour in April 1970, the band took a well-deserved break. Jones and Bonham returned home, but Page and Plant had other ideas. At Plant’s suggestion, the two headed to a cottage in Wales, near the town of Machynlleth, where the singer had spent time with his family when he was a boy. The 18th century home, named Bron-Yr-Aur (“The Golden Breast”) didn’t even have running water or electricity.

By this time, Page already had three new tunes in his pocket: “Immigrant Song,” “Friends” and “Since I’ve Been Loving You.” However, Page and Plant planned to spend their time at Bron-Yr-Aur relaxing, not writing, and taking a break from the demands of their band. “When I look back at what we actually did in 1969 alone, it’s absolutely mind-boggling,” Page said.

But soon enough, the duo began working on new songs – folky, acoustic material that mirrored their bucolic surroundings. “That’s the Way” was developed during a walk around the Welsh countryside, something Page and Plant did regularly during their time at Bron-Yr-Aur. “We had a guitar with us,” Page recalled. “It was a tiring walk coming down a ravine, so we stopped and sat down. I played the tune and Robert sang a verse straight off. We had the tape recorder ready and got the tune down.”

Although “That’s the Way,” with its languid, strummed chords performed in an open-G tuning, was the only full song to emerge from their time at Bron-Yr-Aur, Page also stated that, “It was the tranquility of the place that set the tone of the album.”

Of course, to say that the act of unplugging from urban life at Bron-Yr-Aur was on its own enough to spur Zeppelin’s move toward a more rustic sound would be reductive. “There were three acoustic songs on the first album and two on the second,” Page pointed out, with his admiration for Joan Baez and Bert Jansch made clear on Led Zeppelin, and songs like “Ramble On,” with its strummed acoustic verses offset by power-chord-fortified choruses, highlighting II.

Additionally, by 1970 both Page and Plant had been turned on to British folk acts like Fairport Convention and the more psychedelia-laced Incredible String Band, as well as artists like Joni Mitchell and the Band. “The places the Fairports and the String Band were coming from were places we loved very much,” Plant remarked. “The Zeppelin thing was moving into that area in its own way.”

But, Page noted, “I don’t think you’d ever confuse Led Zeppelin with Fairport Convention or the Incredible String Band. I think they were coming from a much more traditional place, and I was coming from so many different areas.”

There were three acoustic songs on the first album and two on the second

Jimmy Page

Early sessions for Led Zeppelin III had already taken place in November 1969, at Olympic Studios in London, the same facility that birthed Led Zeppelin. But upon returning from Bron-Yr-Aur, Page and Plant reconvened with Jones and Bonham at a new locale, Headley Grange, described by Page as a “damp and cold” 18th century country house in Hampshire that, much like the beloved Welsh cottage, was far removed from the trappings of modern life. There, the group set to work on new material.

“The reason we went there in the first place was to have a live-in situation, where you’re writing and really living the music,” Page said. “We’d never really had that experience before as a group, apart from when Robert and I had gone to Bron-Yr-Aur.”

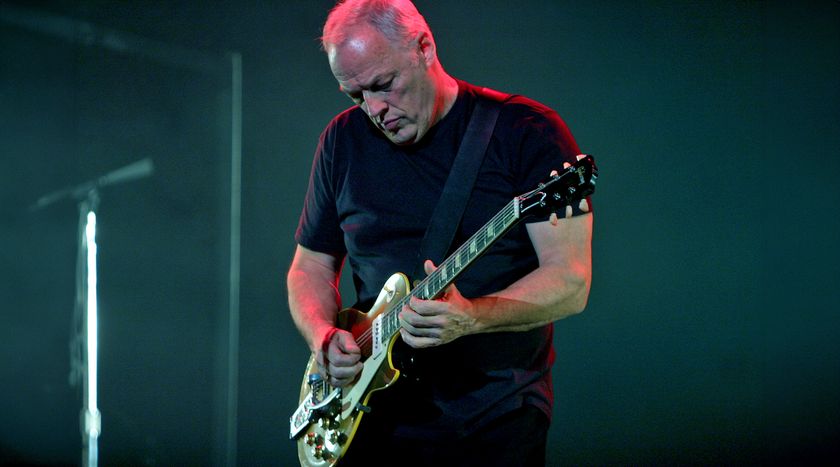

Recording sessions ensued at Headley using the Rolling Stones’ Mobile Studio, with additional work done at Olympic and Island studios. By this time, Page had his electric guitar setup more or less solidified. After playing a 1959 Fender Telecaster on Led Zeppelin, he came upon that most classic of combinations, a sunburst ’59 Gibson Les Paul Standard – purchased from Joe Walsh and subsequently nicknamed No. 1 – through a 100-watt Marshall (though it wasn’t his only amp on the record), just in time for Led Zeppelin II.

The Les Paul is heard on Led Zeppelin III as well, but when it came to the acoustic parts for the record, he turned to a trusty companion: a Harmony Sovereign H1260 that he first purchased in his Yardbirds days and subsequently employed to write all the acoustic songs, and some of the electric ones, on the first three Zeppelin albums.

For III, that modest Harmony also served as his acoustic guitar in the studio (although a 12-string, believed to be a Giannini GWSCRA12-P Craviola, was used sparingly, most noticeably on “Tangerine”). From there, the Harmony remained his primary acoustic both onstage and on record until 1973’s Houses of the Holy, when he acquired a Martin D-28.

As for what he liked about the Harmony? “It helped me come up with all these amazing songs!” he once exclaimed with a laugh. “It encouraged me. It didn’t fight back, and it didn’t go out of tune. It would say to me, ‘Go on, man, give me more! C’mon!’”

We were so far ahead that it was very difficult for reviewers to know what the hell we were doing

Jimmy Page

Led Zeppelin III was released in the U.S. on October 5, 1970, with advance orders registering at almost a million copies. Roughly three weeks later, it was issued in the U.K., where it immediately topped the charts (it soon hit No. 1 in America as well).

Critically, however, the record fared less well, and after its initial peak, sales lagged. While Led Zeppelin were never much of a critics’ band to begin with, this time around they were also, oddly enough, dinged for moving away from the sometimes bludgeoning, overly sexualized sound that many had criticized in the first place.

Some journalists wrote off the acoustic material on III as a mere Crosby, Stills & Nash rip-off. Lester Bangs, writing in Rolling Stone, opined that “the acoustic stuff sounds like standard Zep graded down decibel-wise,” even as he singled out “That’s the Way” for praise.

But as Page commented, “We were so far ahead that it was very difficult for reviewers to know what the hell we were doing. They couldn’t relate to it. Very rarely could they get the plot of what was going on.”

And indeed, there was a lot going on. Led Zeppelin III’s first two tracks, “Immigrant Song” and “Friends” – also the first two composed for the record – laid out the album’s warring styles: electric vs. acoustic, aggressive vs. exotic. But even “Immigrant Song,” with its pile-driving riff and wailing lyrics, held unexpected musical treats, such as the stabbing G minor chords that accent the main F# riff during the outro.

“It pulls the whole tension of the piece into another area or another dimension, just for that moment,” Page explained. “And a bit of backward echo makes it a bit more complete. It’s putting all these elements together that makes the music have depth.”

“Friends,” meanwhile, was the result of Page’s experimentation with an unusual tuning, in this case open C6 (low to high, C A C G C E). The churning, deliberately strummed acoustic rhythm is clearly rooted in folk, though Jones’ mesmerizing string arrangement – which serves as the main accompaniment, along with some light percussion and a hint of synthesizer – suggests an Indian flavor. (As if to acknowledge this fact, in 1972 Plant and Page traveled to Bombay – now Mumbai – and recorded a version of the song with a group of musicians, including sarangi, sitar and tabla players, that they credited as the Bombay Symphony Orchestra.)

We were playing in the spirit of blues but trying to take it into new dimensions dictated by the mass consciousness of the four players involved

Jimmy Page

The rest of side one held numerous treats, in particular “Since I’ve Been Loving You.” While on the surface it seemed of a piece with previous Zep slow-blues behemoths like “I Can’t Quit You Baby” and “You Shook Me,” it was anything but. For starters, unlike those songs, “Since I’ve Been Loving You” was a Zep original. What’s more, it introduced a sort of progressive blues built from a complex chord structure and movement, and used a slow build that erupted in a furious crescendo. Plant described it as “a bit more classy than a 12-bar.”

“It was meant to push the envelope,” Page said. “We were playing in the spirit of blues but trying to take it into new dimensions dictated by the mass consciousness of the four players involved. The same thing goes for the folk stuff, as well.”

Indeed it did. And all of that “folk stuff,” save for the previously mentioned “Friends,” was found on side two of the record, which kicks off with one of Zeppelin’s most stunning interpretations: “Gallows Pole,” which is based on the traditional tune “The Maid Freed From the Gallows.” According to Page, the song emerged suddenly, after he grabbed Jones’ Vega PS-5 Long Neck banjo, an instrument he claimed to have never played before. “I just picked it up and started moving my fingers around until the chords sounded right, which is the same way I work on compositions when the guitar’s in different tunings.”

On the recording, Page played banjo as well as acoustic and electric guitar, with Jones adding electric bass and mandolin. “What happened with Zeppelin was very organic,” Jones recalled. “You find yourself with a bit more time and you sit down with some acoustic instruments, and you start exploring.”

Jones also played mandolin on “Hey, Hey What Can I Do,” a country-inflected acoustic number from the III sessions that didn’t make the final album. He recalled that he had purchased his first mandolin while on tour in America, and said that he probably learned his first tunes for the instrument from the 1969 Fairport Convention album Liege and Lief. “Literally, it was sitting around a fire at Headley and picking things up and trying things out,” he explained.

As for the remainder of side two, “That’s the Way” featured Page on the Harmony acoustic in open-G tuning, as well as on dulcimer and pedal steel – believed to be a Fender 800 model – and Jones on mandolin.

There was also the sentimental pop ballad “Tangerine,” which once again combined Page’s acoustic and Jones’s mandolin to great effect in the verses, and was accented by more pedal steel from Page in the chorus. “Bron-Y-Aur Stomp” is a Lonnie Donegan-style skiffle tune that actually had its origins in a Zeppelin electric jam titled “Jennings Farm Blues.”

While it often sounds like music from the past, it’s a past unlike anything we’ve heard before – and one that possibly never existed at all

The closing track, “Hats Off to (Roy) Harper,” is an acoustic blues that sounds as if Page and Plant exploded the form from the inside out and reconstituted the pieces in cut-and-paste manner. The peculiarity was named for then-current British folk musician Roy Harper, with whom Page had recently struck up a friendship, as a nod to an artist he viewed as uncompromising. “I mean, hats off to anybody who sticks by what they think is right and has the courage not to sell out,” Page said.

The same, of course, could be said of Page and his cohorts with the making of Led Zeppelin III. And yet, while the record introduced a new facet of the band, its ethos was of a piece with their two previous efforts in that it saw them taking sounds and ideas present in rock, blues, folk and traditional music and twisting them into something entirely new.

To that end, the brilliance of Led Zeppelin III, and in particular its folk-based material, is that, while it often sounds like music from the past, it’s a past unlike anything we’ve heard before – and one that possibly never existed at all.

Led Zeppelin’s approach on the record also served to influence their musical future. For their subsequent fourth, untitled album, they returned to Headley Grange and further integrated their folk side into its tracks, in particular on “The Battle of Evermore,” “Going to California” and, most significantly, “Stairway to Heaven,” a song Page said “crystallized the essence of the band.” (The album’s lack of a title, meanwhile, was Page’s reaction to III’s chilly critical reception.)

The band reconvened again at Headley for 1975’s Physical Graffiti, an album that included a III outtake, the Page acoustic instrumental “Bron-Yr-Aur,” and saw them pushing their wide-ranging sound out even further.

But in the end, it’s Led Zeppelin III that, through its embrace of more traditional instruments, unlocked the musical adventurism that flowed freely throughout the band’s subsequent albums. As Plant stated, “The third album was the album of albums. If anybody had labeled us a heavy metal group, that destroyed them.”

For Led Zeppelin, taking a step back on III was a statement that there was really only one direction – forward. “Now that we’ve done [it], the sky’s the limit,” Plant said. “It shows we can change. It means there are endless possibilities for us. We won’t go stale, and this proves it.”

Or, as Page put it, “I was into the ’70s. Our attitude was, ‘Fuck the ’60s! We’re going to chart the new decade!’ We were on a mission.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Rich is the co-author of the best-selling Nöthin' But a Good Time: The Uncensored History of the '80s Hard Rock Explosion. He is also a recording and performing musician, and a former editor of Guitar World magazine and executive editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine. He has authored several additional books, among them Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, the companion to the documentary of the same name.

"Shredding is like talking a foreign language at 10 times the speed of sound. You can't remember anything." Don Felder reveals the unlikely influence behind his iconic guitar solo for the Eagles' “One of These Nights”

"Old-school guitar players can play beautiful solos. But sometimes they’re not so innovative with the actual sound.” Steven Wilson redefines the modern guitar solo on 'The Overview' by putting tone first