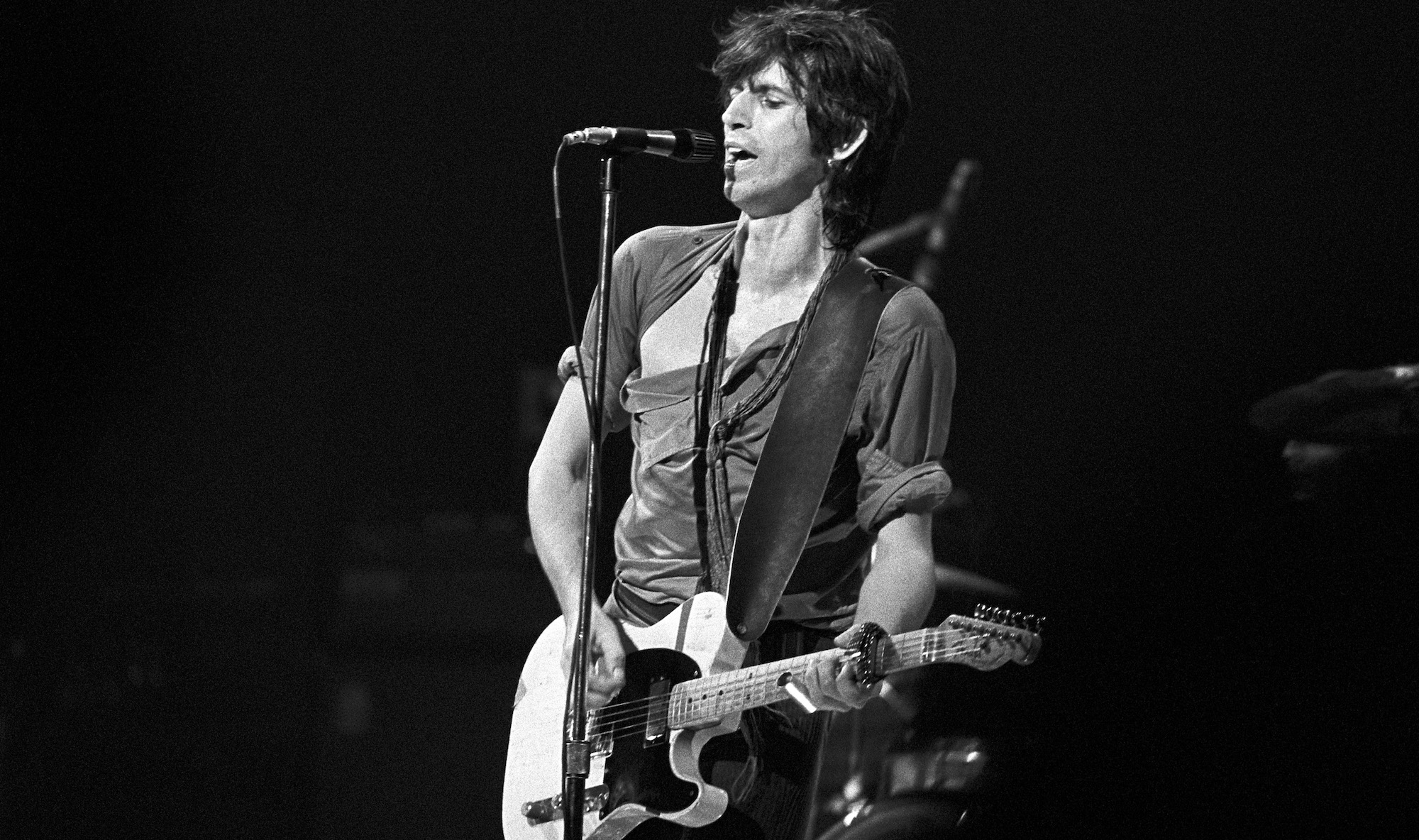

Keith Richards Discusses the Joys of Blending Lead and Rhythm Playing, His Love of Chuck Berry, and More in 1977 GP Interview

"It’s never been the technique thing with me. I’ll never be a George Benson or a John McLaughlin, and I’ve never tried to be," Richards told us at the time.

The following is an excerpt from GP's November 1977 cover story on Keith Richards.

Almost every sentence ever written about The Rolling Stones begins with the word “Mick,” and ends with the word “Jagger” – which is odd, considering that four-fifths of the band’s personnel has remained constant throughout the group’s 14- year, 24-album history.

And from the band's inception as England’s top rhythm and blues outfit, to its present status as one of the world’s most powerful and influential rock and roll bands, the Stones’ principal guitar player has been Keith Richards.

How did you and Brian Jones relate as guitarists?

Really fantastic. But, later, Brian got fed up with the guitar, and he started to wander around to every other instrument. He found that he had this facility for any instrument that might be lying in the studio. He’d play vibraphone, marimba, or harp – even though he’d never touched them before.

He had this incredible concentration, where he could apply it all, and in an hour or so, he’d have it down enough to be used on the record.

When you two first started playing together, who did what?

We were both feeling each other out, because we were all very much into electric Chicago blues. Our styles varied a lot. I was personally more into the commercial stuff from Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley, Muddy Waters, and Jimmy Reed.

For some reason, these were the people Brian had never heard of. He was more towards Elmore James, B.B. King, and Howlin’ Wolf.

On the early Stones tracks, did you work more out of chord forms, or were your lines based on scales or single- or two-string patterns?

I love two-string stuff. That was mainly the influence of Chuck Berry. What interested me about him was the way he could step out of the rhythm part with such ease, throwing in a nice simple riff, and then drop straight into the feel of it again.

Obviously, a lot of your style comes from Chuck Berry.

Oh, without a doubt. When I was learning guitar, I spent so long learning from him and his records.

Do you play off Charlie Watts’ drum accents?

We tend to play very much together. I have to hear Charlie, and I think he has to hear me. I love playing with Charlie – he knocks me out every time.

How do you interact musically with Bill Wyman?

I don’t really know what to say about Bill, because he is, like, the perfect anchor between Charlie and myself. To me, his strong point is that he’s always there, but he’s always unobtrusive. And, for me, straight-ahead rock and roll bass should be there, but you should feel it – it should never stick out so that you actually notice it more than anything else.

A bass should be something that you can walk on, and not have to worry whether there are going to be any holes there.

How was your playing relationship with Mick Taylor?

Always very good. It was a different thing for me. There is no way I can compare it to playing with Brian, because it had been so long since Brian had been interested in the guitar at all. I had almost gotten used to doing it all myself – which I never really liked. I couldn’t bear being the only guitarist in a band, because the real kick for me is getting those rhythms going, and playing off another guitar. But I learned a lot from Mick Taylor, because he is such a beautiful musician.

When he was with us, it was a time when there was probably more distinction between rhythm guitar and lead guitar than at any other time in the Stones. The thing with musicians as fluid as Mick Taylor is that it’s hard to keep their interest. They get bored – especially in such a necessarily restricted and limited music as rock and roll.

That is the whole fascination with rock and roll and blues – the monotony of it, and the limitations of it, and how far you can take those limitations, and still come up with something new.

You’re using a lot more chords onstage than you have in the past.

It’s true. Now – especially with [co-guitarist] Ron Wood – the band is playing a lot more the way it did when Brian and I used to play at the beginning. We used to play a lot more rhythm stuff. We’d do away with the differences between lead and rhythm guitar.

It’s like, you can’t go into a shop, and ask for a “lead guitar.” You’re a guitar player, and you play a guitar. What’s interesting about rock and roll for me is that if there are two guitarists, and they’re playing well together and they really jell, there seems to be infinite possibilities open. It comes to the point where you’re not conscious anymore of who’s doing what.

It’s not at all a split thing. It’s like two instruments becoming one sound. It’s never been the technique thing with me. I’ll never be a George Benson or a John McLaughlin, and I’ve never tried to be. I’ve never been into just playing, as such. I’ve been more interested in creating sounds, and something that has a real atmosphere and feel to it.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Guitar Player is the world’s most comprehensive, trusted and insightful guitar publication for passionate guitarists and active musicians of all ages. Guitar Player magazine is published 13 times a year in print and digital formats. The magazine was established in 1967 and is the world's oldest guitar magazine. When "Guitar Player Staff" is credited as the author, it's usually because more than one author on the team has created the story.

“I’m still playing but I’m covered in blood. Billy’s looking at me like, ‘Yeah! That’s punk rock!'” Steve Stevens on his all-time worst gig with Billy Idol — and the visit to Jimi Hendrix's grave that never happened

"He goes to England and all of a sudden he's on the floor humping his guitar!” Gene Simmons tells how he, Paul Stanley and Ace Frehley followed Jimi Hendrix's lead and gave Kiss some British swagger