“Keep Going Until Everybody Knows Who You Are”: Rory Block Talks the Blues

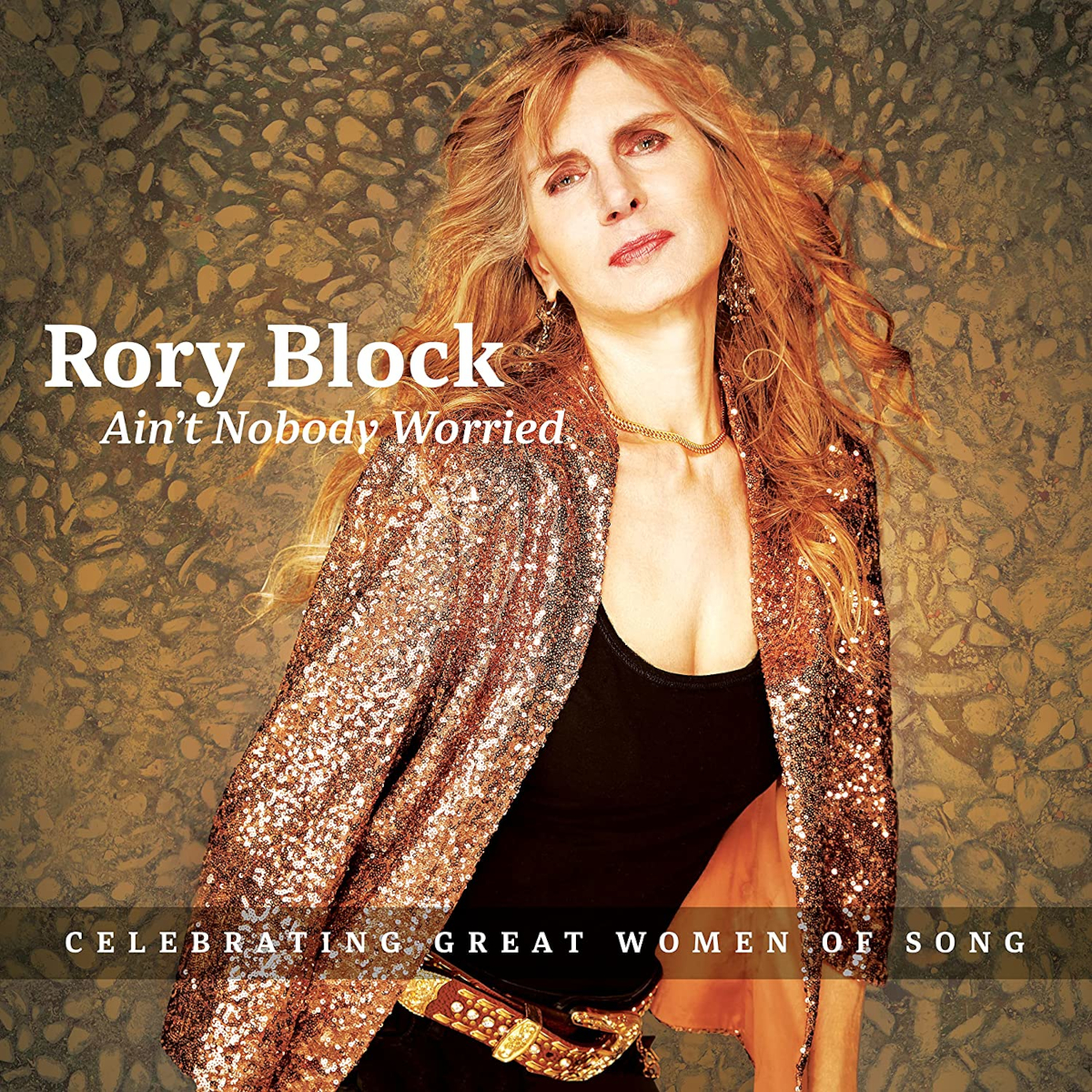

Koko Taylor's “Little Miss Dynamite” gives blues women their due on new album ‘Ain’t Nobody Worried,’ with acoustic covers of Bonnie Raitt, Tracy Chapman, Elizabeth Cotten and more

Rory Block remains one of the premier purveyors of acoustic blues. In addition to honors received over her lengthy career, she won the Blues Foundation’s prestigious Koko Taylor Award for Traditional Female Blues Artist in 2021 as well as the 2019 Blues Music Award for Acoustic Artist of the Year.

Block loves to commemorate her heroes and predecessors, and to celebrate female empowerment

Taylor herself called her “Little Miss Dynamite.” Block loves to commemorate her heroes and predecessors, and to celebrate female empowerment. She’s recorded a host of tribute albums that pay homage to everyone from Robert Johnson to Bukka White to Bessie Smith.

On Ain’t Nobody Worried (Stony Plain), the third volume in her “Power Women of the Blues,” she takes a slightly different spin by honoring a variety of artists, rather than focusing on one in particular.

With her slide prowess, powerful voice and penchant for making a cover sound like her own song, Block is like an acoustic Bonnie Raitt.

Block is like an acoustic Bonnie Raitt

One of the standout tracks on Ain’t Nobody Worried is “Love Has No Pride,” made famous by Raitt, who Block calls “the best singer on Earth.” Block’s take on Elizabeth Cotten’s iconic “Freight Train” is another guitar-centric gem, and her driving version of Tracy Chapman’s “Fast Car” is a cool inclusion because of how well the 1988 hit flows seamlessly alongside older material, such as Gladys Knight’s “Midnight Train to Georgia.”

Most of the song selections are drawn from the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s, which is still relatively recent compared to the folk blues and old-timey music Block generally interprets.

The sole original cut here is a stripped-down and refreshing version of her most popular song, “Lovin’ Whiskey.” Block’s rock-solid rhythm playing anchors the entire affair, and all of the guitar overdubs are her own. The same is true of the vocals, some of which one would swear were done by a group of singers.

Block even plays bass and percussion here. Girl power, indeed!

Why are you so dedicated to playing purely acoustic blues?

The blues was invented on acoustic instruments, so the only way I really hear early American country blues is on an acoustic guitar. You can do whatever you want, but in my opinion the acoustic guitar is the most perfectly suited instrument for the music.

I’m a Martin guitar freak

Rory Block

Is your signature Martin OM-40 from 2004 still your main instrument?

It’s my only instrument. I’m a Martin guitar freak. I’ve seen a lot of wonderful instruments, but in my view Martin has a mystical edge above everything else on the planet – the universe! They are magnificent instruments, unmatched in their historical significance.

Before I owned a Martin guitar, they invited me to pick one off the wall at a NAMM Show. Of course I was floored! I chose an OM-28V [Vintage] because it was the right size and feel. Later I was honored with my own signature model.

Dick Boak and I sat down in a restaurant and sketched out the design ideas on dinner napkins. We made the neck a black-top highway, because I thought the road was an iconic bluesy theme. We added road signs and a railroad crossing in mother of pearl in honor of “Cross Road Blues.”

I stayed with the OM body style because its medium size is pretty much perfect for everyone

Rory Block

I stayed with the OM body style because its medium size is pretty much perfect for everyone. Dick designed the bracing to be sturdier, because of the way that I pound on the guitar, along with a more durable fret wire, since I do a lot of slamming and banging. I use a medium set of Martin Authentic Acoustic SP strings.

While I appreciate a 12-fret neck, I went with 14 frets because it allows more range when you use a capo at the second fret, which I almost always do. It has something to do with the keys I like to sing in.

Standard tuning, dropped D, open D, and open G all work well for me capoed at the second fret. I do that for almost all the Robert Johnson songs in open G, including “Crossroads,” as well as Son House songs in open D, such as “Preachin’ Blues” or “Death Letter” in open G.

What capo do you prefer?

I endorse Shubb because it’s the perfect capo for me. Everybody keeps trying to build a better mousetrap, but for me this one is simply the best. I love the way the Shubb snaps in place. Every capo is going to drive the tuning into another realm, because every guitar has idiosyncratic, unique frets. You have to expect that, even if it’s so marginal that you can barely hear it.

I endorse Shubb because it’s the perfect capo for me

Rory Block

The capo changes all of those subtleties because it changes the starting point. I know what’s going to happen with the Shubb. The bass string is going to go up a tiny bit, and I compensate for that immediately.

How did you wind up using a socket wrench for a slide?

John Hammond told me to try it, because back in the ’60s I couldn’t find anything that fit my smaller hand. He and John Fahey or Stefan Grossman would simply break a wine bottle neck and sand it down, but that was too large for me. No matter what bottle I used, it fell right off.

People started to bring me custom slides made of everything from blown glass to porcelain, but nothing was quite right until John Hammond said, “Go out and get yourself a socket wrench. They come in all sizes.”

I happened to have a friend who owned a gas station, and he let me try on a bunch of socket wrenches. I wound up using a Snap-on Tools 15mm deep well socket, with the end sanded off. It has great percussive power.

I get all the sustain I need with an acoustic guitar and a slide

Rory Block

I recently tried a porcelain slide again that someone had given me years ago, and it sounded much more mellow, buttery sweet and smooth. The metal slide provides a nice edge, and the heavy weight makes it perfect for percussion when hitting the frets or the neck on songs such as Muddy Waters’ “I Be Bound to Write You,” which I do in open G without a capo, or Robert Johnson’s “If I Had Possession Over Judgment Day” [also in open G].

Most modern slide stars play electric guitar. What are your thoughts about sustaining slide notes on an acoustic?

I get all the sustain I need with an acoustic guitar and a slide. As long as you keep the vibrato going, there’s no limit to the sustain other than the diminishing volume because of the law of thermodynamics [i.e., the total energy of an isolated system is constant].

Very interesting. Is it true that you didn’t have much of a grasp on slide until Bonnie Raitt inspired you with a session performance?

I couldn’t figure out what I was doing wrong until later, when I first recorded “Ramblin’ on My Mind” and Bonnie played a solo on it

Rory Block

I was already playing slide, but very badly. I was struggling, so for years I would play Robert Johnson’s material without a slide. I was very nervous about it. I would overshoot or undershoot, and the note would be sharp or flat. I didn’t have good tone, and the vibrato was too fast and buzzy.

I couldn’t figure out what I was doing wrong until later, when I first recorded “Ramblin’ on My Mind” and Bonnie played a solo on it. When we were mixing, the engineers isolated her track and I heard how her playing was so cool and relaxed.

I wrote about this in my book as well [2011’s When a Woman Gets the Blues], so I’m quoting myself, but it sounded like she was taking a stroll up the neck on the strings. I noticed that her vibrato was a wonderful, funky rocking back and forth. It wasn’t fast and nervous like what I was doing.

Listening to her gave me a bunch of ideas to try, including that thing she does where she leaps up from a note with a quick slide right off the string.

Slide is a Zen thing

Rory Block

As a guitar player it often happens that you reach a plateau where you think, I’m stuck playing the same old stuff. I need some new ideas. Listening to Bonnie’s slide playing on that track was a profound jolt of inspiration. It was a revelation about all the things I needed to work on and learn, and it changed the way I practiced.

After a while, I found the pocket. I always say, “Slide is a Zen thing.” After that I started moving forward, learning to do the things that I now teach.

Such as?

For years, I felt completely unable to solo. My thing was sticking with the classic arrangements as closely as I could. But over time I realized that I would have to branch out and develop the ability to improvise.

I’ve since discovered that if you think you can’t do a solo, try singing it first. My husband, Rob [producer Rob Davis], encouraged me to do this when he said, “You play the slide the way you sing.” It hadn’t occurred to me that I could first sing the solo that I was hearing in my head, and then learn to play it on slide. That can help a lot for someone like me who didn’t quite know how to begin.

The more you experiment, the more your hands learn where melodies play out on the neck

Rory Block

Soon I discovered that the more you experiment, the more your hands learn where melodies play out on the neck. I don’t do this anymore, because so many ideas have lodged in my brain over time, but that’s how I developed my slide soloing.

Years ago when I was recording the original version of “Lovin’ Whiskey” [for 1986’s I’ve Got a Rock in My Sock], Bud Rizzo played the heart-wrenching solo on electric guitar. I sat next to him in the studio and sang what I had in mind.

That’s an example of what I’m talking about. If you can hear it and you can sing it, then you figure out how to play it. For the version of “Lovin’ Whiskey” on Ain’t Nobody Worried, I decided to follow what Bud did note for note on acoustic, and I feel like it has come full circle.

What are the origins of your very unique freehand plucking approach?

When I was growing up, my dad played claw-hammer banjo in a style called frailing. That style incorporates an up pluck, a down slam with your fingers, your palm landing on the instrument like a drum, and just this continuous back-and-forth, up-and-down and snap-and-thump.

He showed it to me when I was about eight years old, and it embodied everything that I applied directly to Robert Johnson – that and a little bit of rolling out notes in a flamenco style.

Everybody was introduced to the guitar with that alternating bass, and everybody knew about Elizabeth Cotten

Rory Block

You chose Elizabeth Cotten’s “Freight Train” to close out Ain’t Nobody Worried, and you write in the liner notes how she was the nanny to the Seeger children, and that you believe her “Cotten picking” could be the most influential guitar style ever created.

Yes, because her style is incorporated into almost every fingerpicking style on Earth. When I went to summer camp as a young girl it was run by Pete Seeger’s brother, John Seeger. So it was a music-oriented camp, and everybody was playing Cotten picking.

Everybody was introduced to the guitar with that alternating bass, and everybody knew about Elizabeth Cotten. So in my world, everybody recognized that style.

Who are some up-and-coming acoustic blues ladies that you feel deserve wider recognition?

Some of my guitar students really stand out to me. Lisa Rich, a super-talented blues guitarist from Connecticut, played “Preaching Blues” so hard it shook my whole house, but she has since gone on to other pursuits.

Donna Herula, who was also once a student of mine, is another very strong slide player. She’s been making records and gaining recognition.

Heidi Holton is another former student who is doing well. I have produced two recordings for her and consider her to be a very strong up and coming artist.

Shari Kane out of Ann Arbor, Michigan, is also an outstanding slide player. So there are definitely strong blues ladies out there building careers.

The biggest piece of advice I like to give to players is to keep going until everybody knows who you are.

Order Ain’t Nobody Worried by Rory Block here.

Browse the Rory Block catalog here.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Jimmy Leslie has been Frets editor since 2016. See many Guitar Player- and Frets-related videos on his YouTube channel, and learn about his acoustic/electric rock group at spirithustler.com.

“We’d heard Jimi Hendrix, we'd heard the Who, but now we finally got to see these guys. And watching Jimi Hendrix burn his guitar….” Grace Slick on Hendrix at Monterey, Jefferson Airplane and the Spanish origins of “White Rabbit”

“I’m still playing but I’m covered in blood. Billy’s looking at me like, ‘Yeah! That’s punk rock!'” Steve Stevens on his all-time worst gig with Billy Idol — and the visit to Jimi Hendrix's grave that never happened