Julian Lage Discusses Jazz as an Abstract Modernist Art Form and the Magic of Improv on His Bravura Blue Note Debut

Lage and his trio honor the Blue Note tradition with a spiritual offering for a troubled modern world.

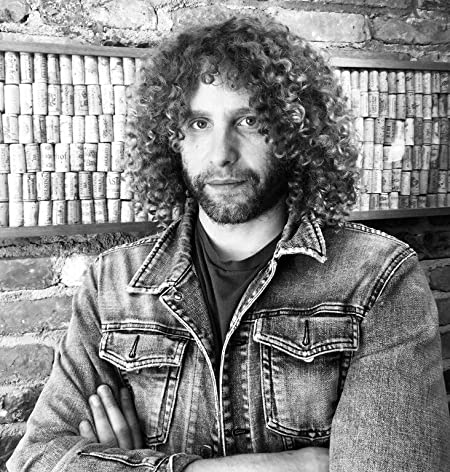

Julian Lage has had a restless six-string spirit for practically his entire life. A guitar prodigy, he became professional at the age of seven and had performed with Carlos Santana, recorded with David Grisman, and appeared on the Grammy Awards before he hit his teens.

As a player, Lage is deeply rooted in jazz technique and history but also equally adept at rock, pop, standards, classical, country, improvisational music, and more.

Since launching his solo career in 2009, the exploratory artist has released albums that find him playing in duo, trio, quartet, and quintet configurations, in collaboration with musicians like Wilco’s Nels Cline (2014’s Room) and the Punch Brothers’ Chris Eldridge (the same year’s Avalon), or even centered around a specific guitar, be it a 1939 Martin OOO-18 (2015’s World’s Fair), a Fender Telecaster (2016’s Arclight), or a 1956 Gretsch Duo Jet (2019’s Love Hurts).

His newest record, Squint, sees the 33-year-old continuing his stylistic adventures with a record that presents him in trio format with bassist Jorge Roeder and Bad Plus drummer Dave King.

The album turns away from the shorter-form, pop-dominated content of its predecessor, Love Hurts, in favor of a looser and more improvisational approach that reveals the guitarist’s love for early rock and blues, as well as songbook standards and jazz classics. And it’s all tied together by Lage’s reverence for, and recognition of, the history behind his new label, the legendary Blue Note Records, as well as an acknowledgement of the turbulent cultural moment in which the album was created.

Lage sat down with Guitar Player to discuss the making of Squint, and also went deep into his history as an improvisational guitarist. As for what continues to motivate him as an artist, he says, “I’m really interested in the evolution of the guitar. And I feel like I stand on the shoulders of giants in that respect. Anything I’m doing wouldn’t exist without the people that came before me, and also without what my colleagues are doing now.

“So my music is a nod to that idea, and it also, hopefully, has a certain sense of inventiveness to it as well.” Lage laughs. “And sometimes maybe it’s just an inventive way of nodding. But for whatever reason, that’s the kind of thing that gets me excited.”

'Love Hurts' was a record we made after we had played, I think, three shows ever as a trio. So it captured a sense of excitement and freshness that was so wonderful

This is your second record in a row with Jorge Roeder and Dave King. But whereas your previous effort together, Love Hurts, felt more structured, this one leans heavily on improvisation.

If we’re talking about the way this particular trio metabolizes songs, you can’t not look at the improvisational language and, even further than that, you can’t not develop it and cultivate it and do things to substantiate the presence of improvisation.

Love Hurts was a record we made after we had played, I think, three shows ever as a trio. So it captured a sense of excitement and freshness that was so wonderful. But over the couple of years of touring with this ensemble, we realized that the improvisational dynamic that we share is really not accidental. It’s as considered as the songs in terms of the ways we solo and the freedom we like to present and the type of risks we like to take. That’s the meat of the message.

Can you talk to us about the intention behind Squint?

I wanted to celebrate a couple of points. One of them being, here we are making a record for Blue Note. What does the music from the Blue Note tradition mean to me? A really big centerpiece of that question, or the answer to that question, is it’s swing music played by bass, drums, and a soloist.

In the past I think I’ve looked more at combining early rock and roll with jazz or more folkloric or orchestral classical music, all with a sense of improvisation. But this time it was, “Let’s celebrate jazz music from an abstract modern perspective.” Which is kind of another way of saying “Blue Note,” right?

The second part of the answer would be to say that I wanted to make a record that shows the band as it has evolved, and in a way that hasn’t been documented in the studio yet.

And finally, another point about this record is that we made it during this critical time in human history – the pandemic obviously being a part of that, but also just the reckoning of social justice and systemic racism and gender inequality.

So I think the temperament was, “Let’s make music that in some respect honors that there’s a lot of pain in the world and there’s a lot of healing that needs to happen. And let’s think of these songs as almost like a spiritual offering.”

Several of your guitar passages on the album were improvised to speeches. What led you to do that, and how does improvising to the human voice influence your phrasing and your dynamics and your note choices when you translate that cadence to guitar?

I became really interested in, from a place of humility, playing music that I felt was respectful and sympathetic to, let’s say, a lecture by James Baldwin or Nikki Giovanni, talking about leaders not just within the African-American community but leaders of humanity. And talking about the stuff that matters. And if that’s their message, which in and of itself is essential and critical and impactful, how are they using speech to convey that?

I started realizing that I wanted to build a strong relationship in my playing between what I want to say and how I say it. And that goes for playing with other people, too. You have to play something that supports what they’re saying but also take into consideration the rhythms and the cadences. What kind of lines do you play? Do you dominate it with chords? Do you complement it with the upper register? It teaches you about using the guitar as an extension of your speaking voice.

Another thing I’ll say is there’s something about speech and communication, the freedom of it, that I’m fascinated by. But then when it comes to tones and rhythms and pitches on the guitar, there’s something that gets a little more conservative and a little more rational. So I wanted to marry my capacity as a communicator of language with my message on guitar.

Is there a particular spot you could point to on the record that is the result of your improvising to the human voice?

I think if you listen to “Familiar Flower” you get a good sense of that. There’s a lot of variety – rhythmically, phrase-wise – in that song, where I’m changing tempos, I’m changing registers, and it’s very conversational with the band. When I hear my playing on that song, it sounds more like how I speak. To a certain degree, “Short Form” has it, too.

What I was starting to understand was that just because it’s improvised doesn’t mean that it’s not as legitimate a composition

Does improvisation ever lead to songwriting, or is it a completely separate discipline?

Well, on the new record, “Saint Rose” is an example of almost exactly that. That song was pretty much just an improvisation – the melody, the riff, everything. I was like, “Oh, that sounds good. I’ll write it down. Now it’s a song.” So good, bad, or different, I think what I was starting to understand was that just because it’s improvised doesn’t mean that it’s not as legitimate a composition.

It’s so funny, because as someone who’s been obsessed with improvisation since I was a little boy, I should know that. And yet I think there’s an old-world paradigm of, “If it’s written, it’s real, and if it’s not written, it’s ‘less than.’” But no one ever said that. I just kind of believed it. So it’s about looking to improvisation as a legitimate form of composition.

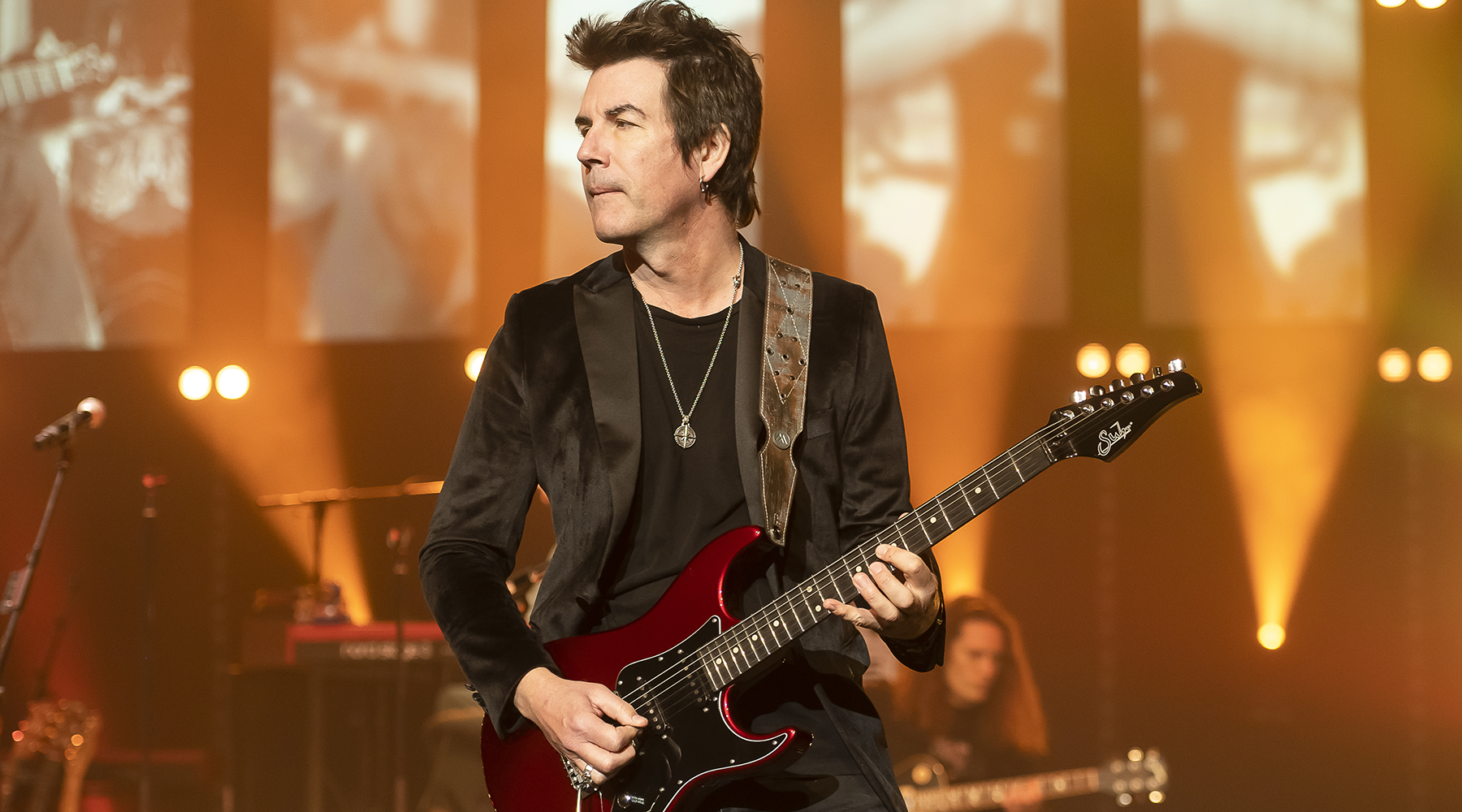

What was your main gear setup on Squint?

My guitar was a Collings 470 JL [Lage’s signature model]. We just made that guitar, and it’s really cool. The pickups are by Ron Ellis and are in the tradition of Duosonic pickups, and we put it through a Magic Vibro Deluxe amp, which is basically like a black-panel Deluxe, and a tweed ’59 Fender Champ at the same time.

And then on a few tracks – “Day and Age,” “Saint Rose,” “Twilight Surfer” – I’m using an incredible 1955 Les Paul that I love. Otherwise there’s a [Strymon] Flint pedal and a clean boost. But the Collings through those two amps is kind of the heartbeat of it. My sound is basically just a guitar turned up. [laughs]

Records for me are an excuse to go deeper into something that I want to go deeper into. It’s a way of fortifying an aesthetic or an interest or a curiosity or a question

Each of your records seems to have a distinct course, whether it’s the size of the accompanying ensemble, the instruments you play, or the style of music you approach. Is your intention to use the studio as a tool to explore your musical personality?

Well, that’s a killer question. For me that’s totally the point. Records for me are an excuse to go deeper into something that I want to go deeper into. It’s a way of fortifying an aesthetic or an interest or a curiosity or a question. I think of it as kind of like, “If you can sort it out in record form, you’re probably going to have to become a better player to do it.”

Do you know what I mean? Versus making a record that just tells people, “Oh, I do this thing natively.” And I say this not as a “less than” proposition – it’s an equally great proposition.

It’s a way of saying, “Here’s this thing that I do and we need to capture it.” And the records I make, I think they’re at least partially that. But they’re also partially, “What’s the thing I would love to be able to do?” Once I figure that out, then that’s what the record is going to be about.

- Squint is out now via Blue Note.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Rich is the co-author of the best-selling Nöthin' But a Good Time: The Uncensored History of the '80s Hard Rock Explosion. He is also a recording and performing musician, and a former editor of Guitar World magazine and executive editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine. He has authored several additional books, among them Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, the companion to the documentary of the same name.

“We’d heard Jimi Hendrix, we'd heard the Who, but now we finally got to see these guys. And watching Jimi Hendrix burn his guitar….” Grace Slick on Hendrix at Monterey, Jefferson Airplane and the Spanish origins of “White Rabbit”

“I’m still playing but I’m covered in blood. Billy’s looking at me like, ‘Yeah! That’s punk rock!'” Steve Stevens on his all-time worst gig with Billy Idol — and the visit to Jimi Hendrix's grave that never happened