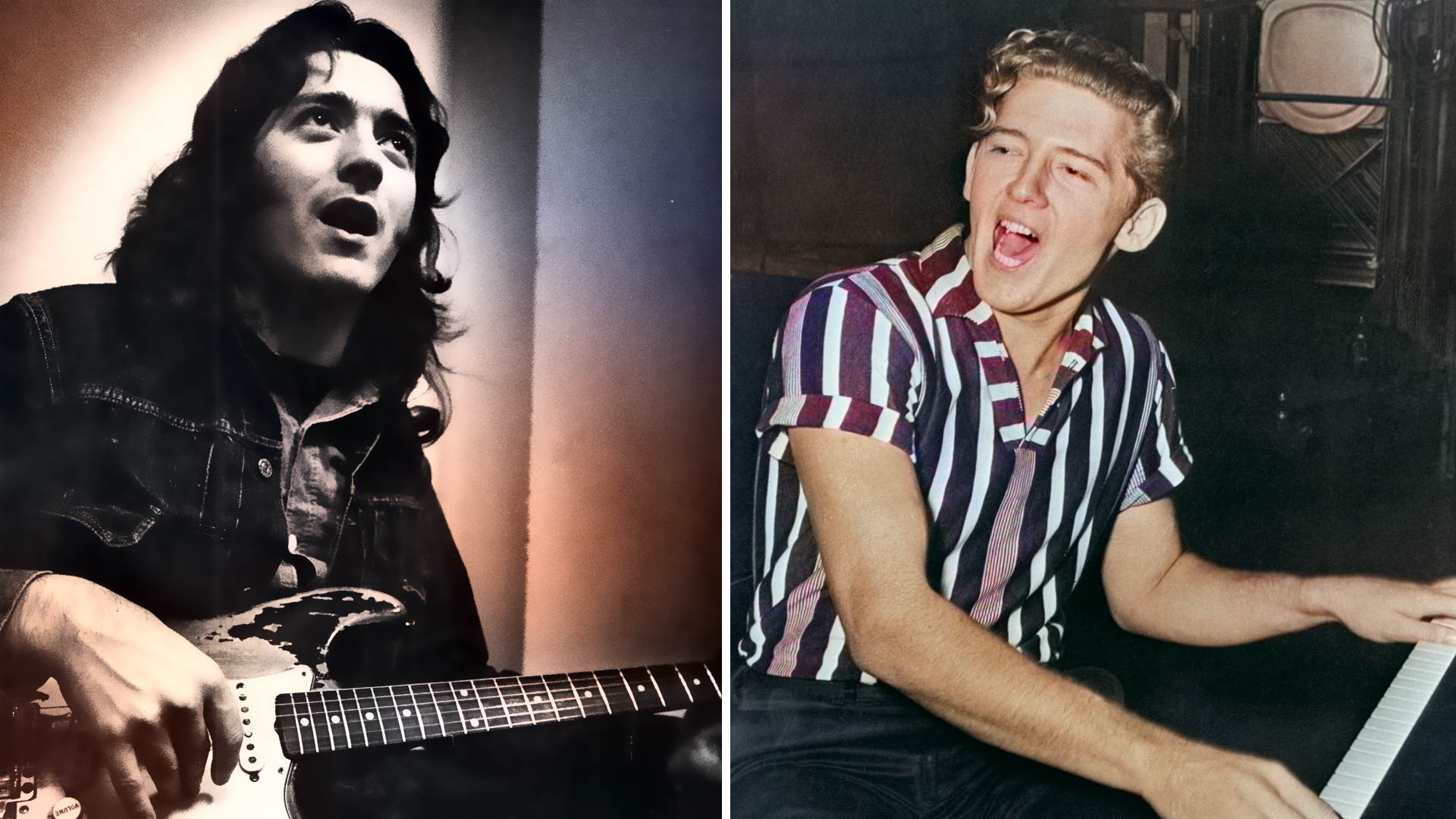

Josh Smith: "It Was Really Important to Keep it as Old-School Live as Possible. Kenny Burrell Didn’t Go Back and Fix Any of His Solos, So I Wasn’t Even Tempted"

The genre-fusing guitar veteran reveals how he expanded his usual horn section to an all-brass big band on his adventurous, swinging new album, 'Bird of Passage.'

Former Floridian Josh Smith has carved out his place in the guitar firmament through his high-powered, hybrid-picked, heavy-stringed mixture of blues bends and jazz sophistication. He was already playing professionally at age 13, touring the same circuit as contemporary prodigies Derek Trucks and Joe Bonamassa. By the end of the 2010s, Smith – just 35 – already had two decades of touring under his belt and four records under his own name.

Looking to broaden his horizons, he and his wife moved to Los Angeles, where he began plying his trade as a sideman. Major gigs followed, including tours with 2006 American Idol winner Taylor Hicks and Raphael Saadiq, and backing Mick Jagger at the 2011 Grammy Awards and Kennedy Center Honors.

Smith still found time to release a slew of solo records and to build a home studio, Flat V, where he records his own music as well as that of others. He has also built a burgeoning career as a producer for Reese Wynans, Eric Gales, Andy Timmons, Jimmy Hall, Larry McCray, and others.

For his latest release, Bird of Passage (Flat V Studios), Smith expanded his compact R&B horn section into a full big band, and eschewed saxophones in favor of an all-brass group of multiple trumpets, trombones, and French horns. Such decisions raised interesting questions, and Smith was game to answer them all.

Why do a big-band record?

"I was always curious what it would sound like to do a very traditional Blue Note big-band-style record, but with me playing like myself over the top of it.

"One of my best friends, [Smith’s bassist] Calvin Turner, has been prodding me to do it for years. He wrote the record with me and arranged the horns. I’ve done a smaller R&B horn section before, but these arrangements have a vibe like Quincy Jones, Sinatra with Count Basie’s band, and Grant Green or Kenny Burrell with a big band. I wanted to keep it around that 38-minute Blue Note length, and I wanted to mostly play my Telecaster and use my normal tone."

Did Calvin study arranging?

"He did. He’s arranged horns on pretty much every record I’ve produced. He said, 'I would like to do this slightly differently. I think I’ll use French horns instead of saxes.' And I said, 'I’ll leave that part up to you.' He’s much smarter at those things than I am." [laughs]

What did you record first?

"Doing a big band is not easy, especially with a low budget. My studio here is great, but not big enough for that. We tracked the quartet – me, Calvin, Lemar Carter on drums, and Larry Goldings on organ – here, 100 percent live. Calvin had written out very meticulous charts for the horn parts. We were all reading, but Lemar had to be the most cognizant of the important hits.

"Calvin said, 'Lemar, I need you to hit this,' or, 'Larry I need you to hit this.' We would make notes on our charts and then play it down live. I already knew where the big moments were. Calvin had sent me MP3 files with the horns played by a synthesizer so I could listen and say, 'I like this,' or, 'I don’t like that.' That being said, I’m playing melody most of the time. It was more the other guys who focused on the hits so they would line up with the horns."

Did you play to a click?

"Yes. We finished the quartet tracks in one day, and then Calvin and I flew to Nashville to do the horns. We work with those guys a lot and have a good rapport. It was really important to me to do the horns in complete takes, so everything you hear is one pass. There’s no stacking; it’s a big band. They played it down just like we did, as if it was a gig."

Once the horns were added and you heard it back, did you feel like you wanted to go back and re-record anything that you played?

"No, it was really important to me to keep it as old-school live as possible. Kenny Burrell didn’t go back and fix any of his solos, so I wasn’t even tempted."

Kenny Burrell was probably responding to horn players in real time, whereas while you were playing with the horns in the back of your mind, they weren’t actually there.

"You’re right. In hindsight I could have maybe changed some things to go with the horns a little more. I didn’t really think about it that way. I had also lived with the quartet versions for a few weeks before we did the horns, and they had grown on me."

Do you think the concept changed how you played when recording with the quartet?

"Not consciously, but knowing that there were gaps that would be filled meant I didn’t need to fill everything. For example, on the slow blues, 'Brand New,' I knew there was going to be the big-band Sinatra-type thing, so I didn’t play through all the holes.

"On 'The Wayfarer,' there’s a big ramp up in the middle of the solo where we go from minor to major toward this big release. I knew when we got to that release there were horn stabs underneath me. I didn’t hold myself back, but I was at least cognizant of that."

“The Wayfarer” is epic. It’s like a big-band jazz version of a Gary Moore power ballad.

"Calvin wrote it. He sent me a demo of him playing guitar almost chord-melody style but said, 'I want you to approach it like Roy Buchanan.' The second he said that, I knew exactly how the song would sound. I’m really proud of it. It has a flow from beginning to end, where it never stops building."

What guitars did you play for the tracking session?

"It was recorded in 2019, when were still prototyping my Ibanez [FLATV1] signature guitar, so for 75 percent of the record it was my main Chapin T-Bird. On 'Brand New,' I’m playing a P-90–equipped archtop made by Jon Case from London for that T-Bone Walker thing. On 'Hopeless Quarters,' I’m playing a Ronan guitar with a vintage DeArmond pickup and flatwound strings. That’s the most jazzy tone on the record.

"The amps were the same on every song: my Morgan JS12, which is my signature Princeton-type combo with a 12-inch speaker, combined with a ’55 dual-rectifier tweed Fender Bassman I got from [Joe] Bonamassa. They were on together the whole time, along with my main distortion, the Lovepedal Tchula, and a TC Flashback Mini with my slapback delay TonePrint."

The first short solo on “Rare Plus” sounds like there’s an octave device on the guitar.

"It’s Larry doubling me. It’s a lick I improvised and Calvin wrote it out for Larry, who read it down. I didn’t know Larry very well, but I’d met him many times and was a massive fan. There was nobody else I would call for this project. It was a thrill having him at my studio. He’s a monster."

How did you mic the guitars?

"I had two old Shure Unidyne 57s, one on each amp. I also had a Mesanovic ribbon mic, which is like a Royer, on the Morgan. I actually prefer it to the Royer for guitar. I also used a Neumann U 67–style for the room sound. We were all in the same room, but our amps were isolated. The only thing in the room with us was the drums."

Obviously, touring this project would be difficult, but would you consider a one-off show to offer as a video?

"I actually did a performance of 'The Wayfarer' via satellite with the Army Jazz Ambassadors, their top-flight big band. That video came out on Memorial Day. They played live, and then I overdubbed on top, but we hope to do it in person in the future."

There is also the WDR Big Band in Germany…

"… I reached out to them already." [laughs]

You’re way ahead of me.

"There are a lot of big-band societies around Europe, as well as university bands. I’d love to do some of that. I have these great charts and I’d like to try to take advantage of them. There is also a plan to book a gig in Nashville so I can use the guys on the record and get a video recording. That would be a blast."

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“I did the least commercial thing I could think of.” Ian Anderson explains how an old Dave Brubeck jazz tune inspired him to write Jethro Tull’s biggest hit

"This 'Bohemian Rhapsody' will be hard to beat in the years to come! I'm awestruck.” Brian May makes a surprise appearance at Coachella to perform Queen's hit with Benson Boone