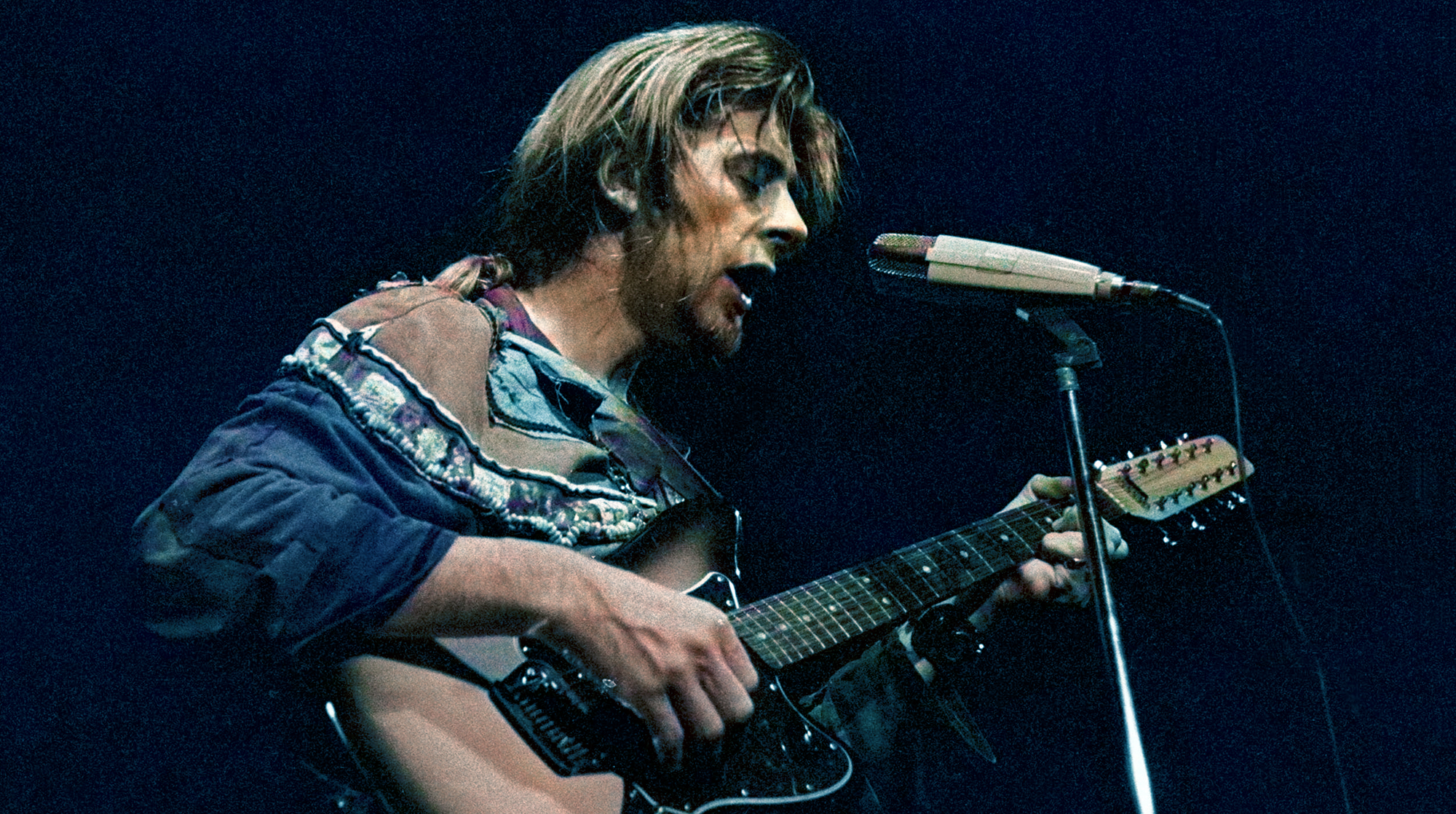

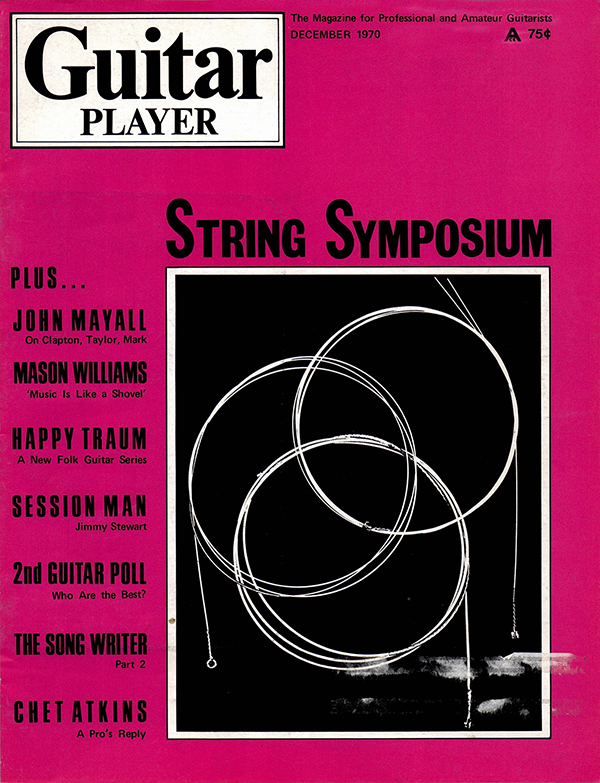

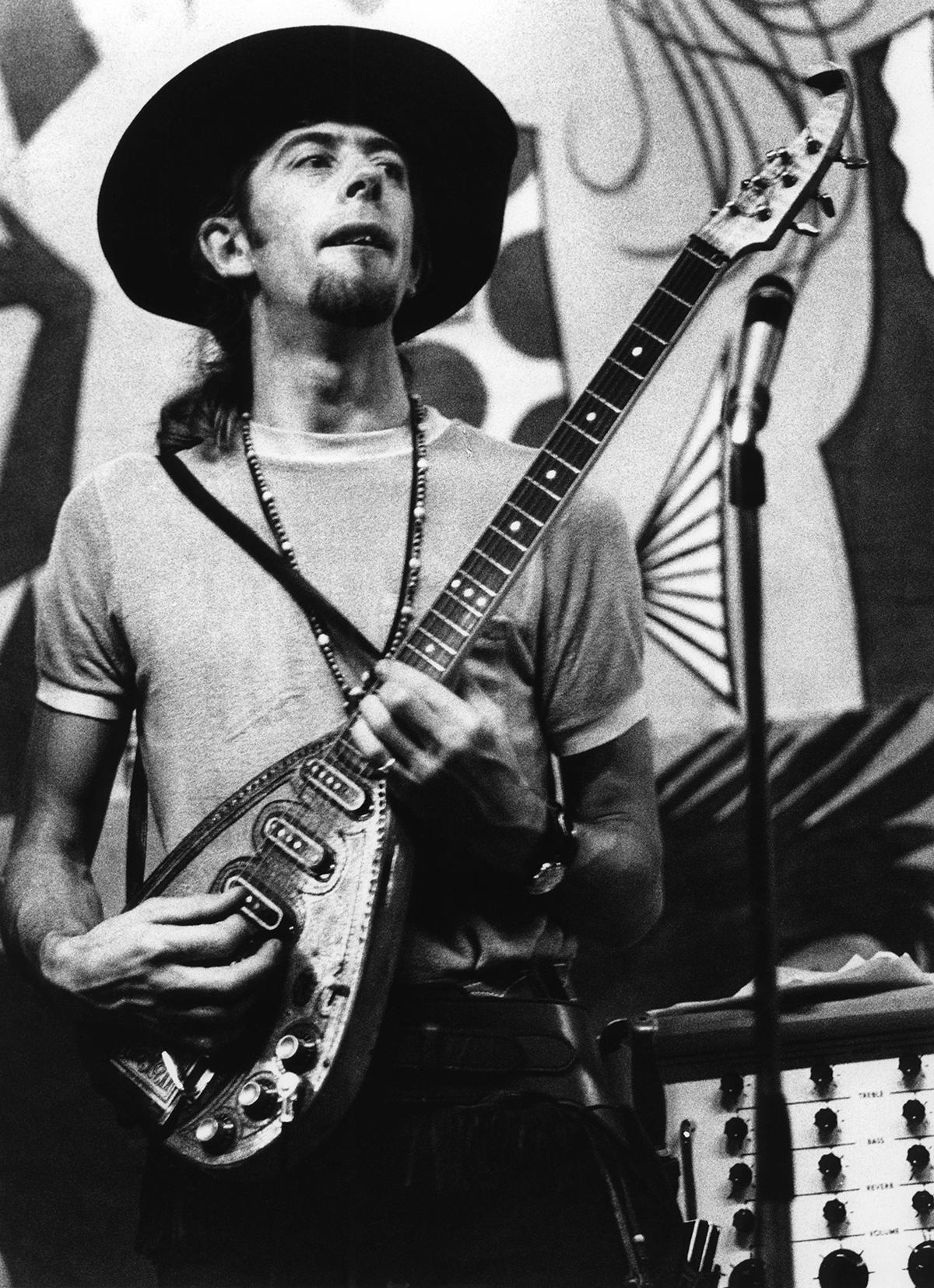

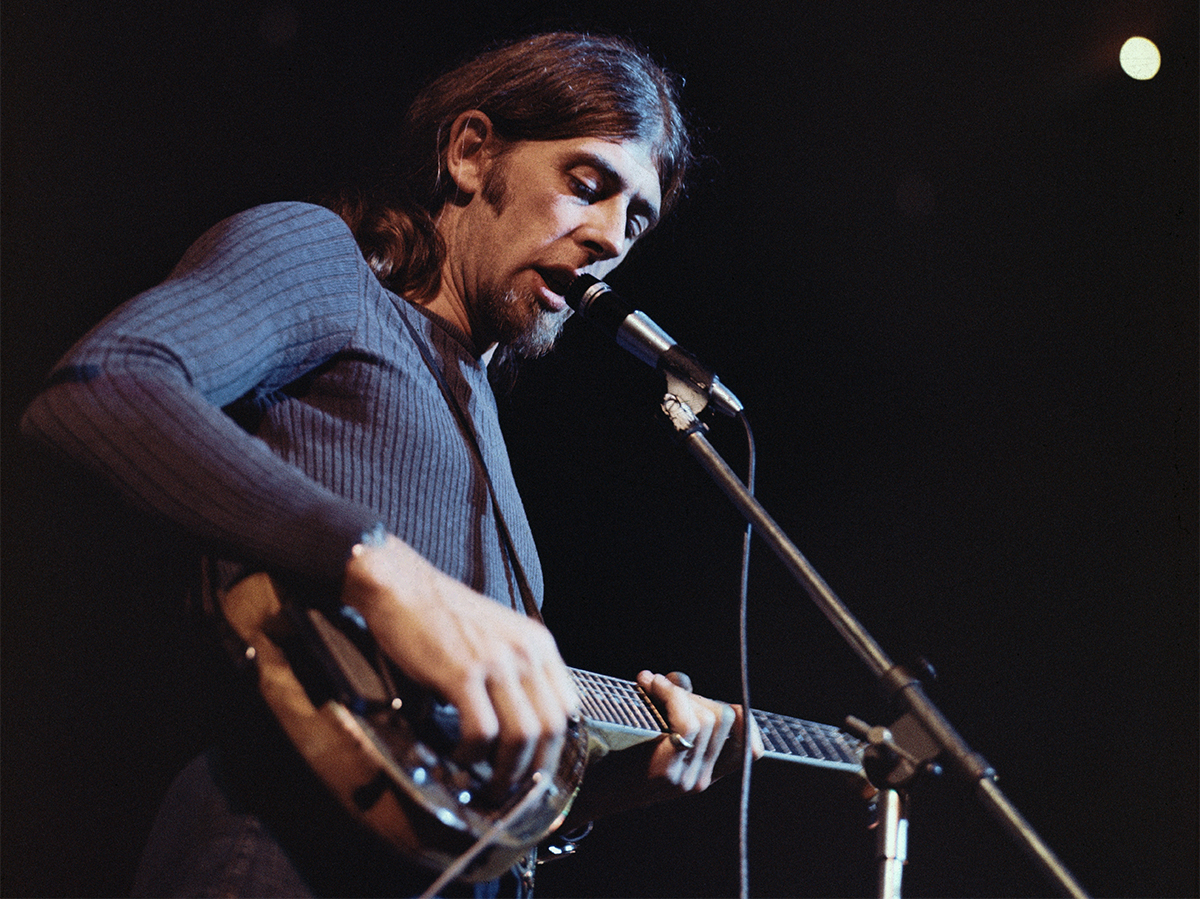

"By the time Eric left we were getting known. The Clapton cult as such had started." John Mayall recalls Eric Clapton, Peter Green and Mick Taylor in Guitar Player's December 1970 issue

We remember John Mayall on the first anniversary of the blues legend's death with a classic interview from our vault

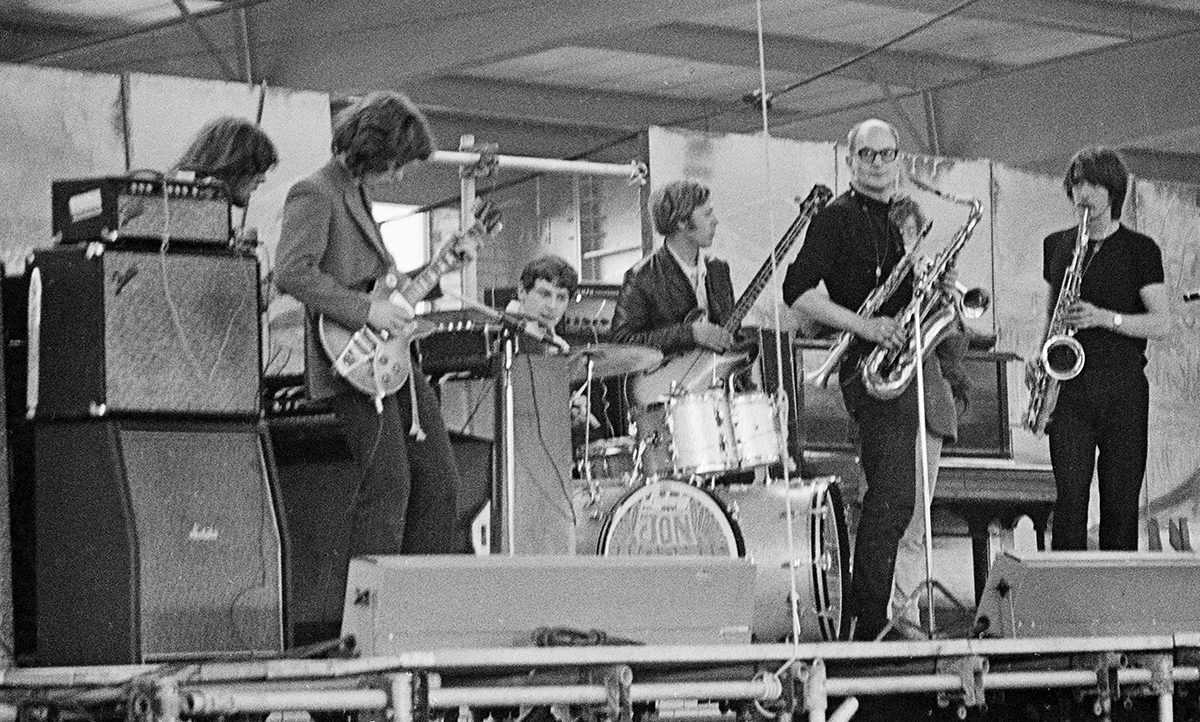

Eric Clapton, Peter Green, Mick Taylor, John McVie and Mick Fleetwood are among the most famous musicians to emerge from Britain's 1960s blues scene. Remarkably, each of them rose from the ranks of John Mayall's Bluesbreakers.

Although he was never as celebrated for his guitar playing as he was for helping to launch the careers of his sidemen, Mayall was an undeniably key figure in the history of rock, blues and even pop — it was he who turned Paul McCartney on to the charms of the Epiphone Casino, a guitar that his fellow Beatles guitarists John Lennon and George Harrison adopted as well.

On the one-year anniversary of his death, on July 22, 2024, Guitar Player celebrates Mayall's life by republishing our classic interview with him from our December 1970 issue.

John Mayall was an elder statesman of English blues who'd been transported to a life in Los Angeles when Guitar Player caught up with him for an interview in the December 1970 issue. By then his group the Bluesbreakers had been the breeding ground for Eric Clapton, Peter Green and Mick Taylor, each of whom was among the most celebrated electric guitar players of the day.

Contributing editor Fred Stuckey, who conducted the interview and wrote it up for the magazine, noted the irony of Mayall’s position in that first year of the new decade.

“In the middle of 1969, while the rock world was spewing out countless copies of Eric Clapton and the Cream’s hard rock sound, Mayall dropped the organ and drums for the harp and guitar and a subdued, low-volume blues. He hired Jon Mark on acoustic guitar and Johnny Almond on flute, tenor and alto. The end product was a much lauded tour, two record albums — The Turning Point and Empty Rooms — and a hit single, ‘Room to Move.’”

Mayall's restrained sound at the start of the decade revealed a more thoughtful approach to the blues and a propensity to continue evolving his music's sound and style. At the time of the interview, he had released USA Union, on which he retained the format and music direction but changed up his band to include Harvey Mandel on guitar, Larry Taylor on bass and Sugar Cane Harris on electric violin.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Stuckey found Mayall a willing interview subject — “choosing his words carefully and pausing to formulate his thoughts” — and noted his modesty:

“By his own admission, Mayall lacks the technical mastery of the guitar shared so uncommonly by the musicians he has worked with in the past. But he plays with the unpretentious, spirited air of a man who knows his idiom. Mayall knows 12-bar blues as well as Renoir knew nineteenth century French impressionism. And Mayall, while not particularly a guitarist, has influenced blues guitarists as much as anyone else in music.” This interview has been edited for brevity.

How have you been?

Just fine. It is sort of strange that Guitar Player would want to interview me, because the magazine is usually reserved for people who play the guitar. I can hold one in my hands and pluck a few notes, but it’s very hit and miss. I have no knowledge of music, you know.

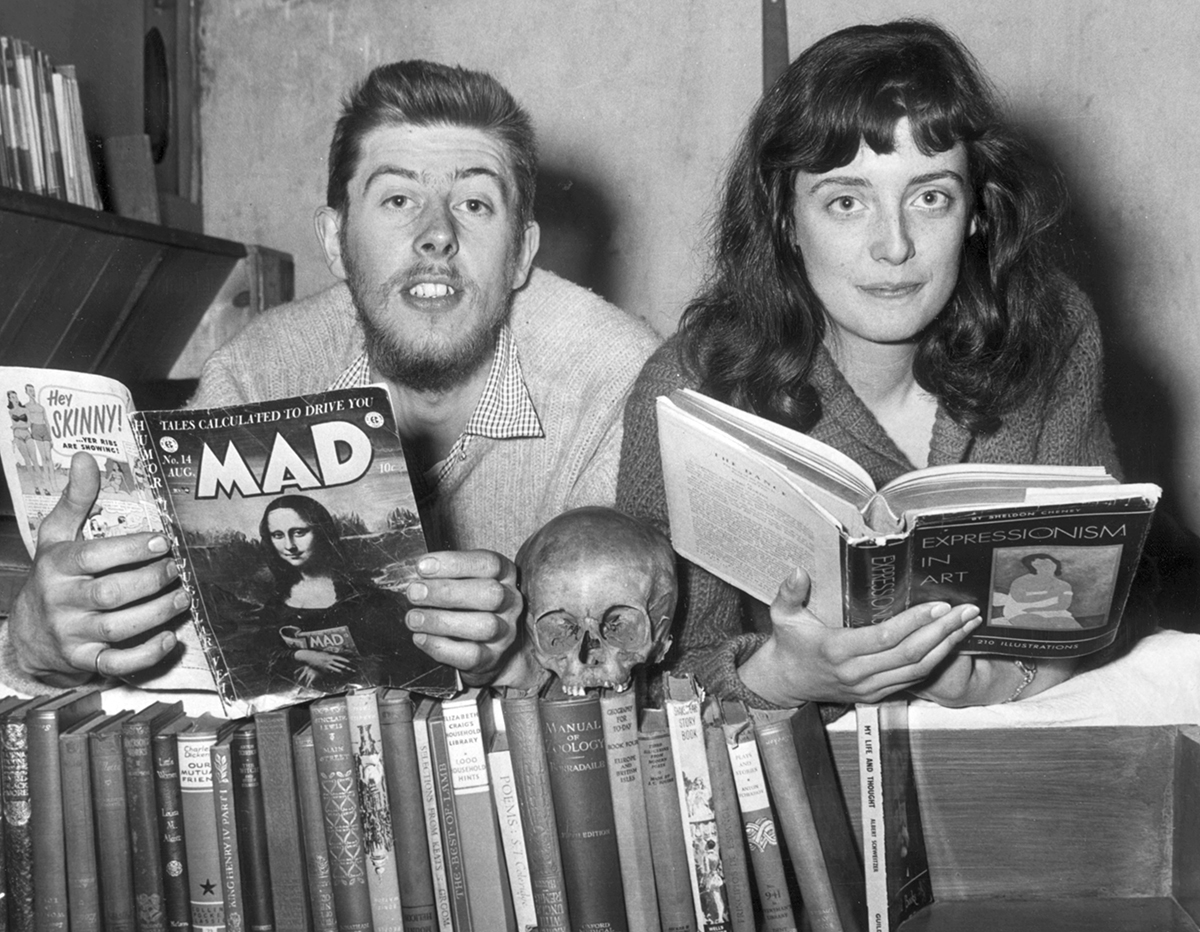

That doesn’t seem to bother your fans. How did you happen to get into the business?

I heard a lot of music through my father’s record collection. He was a guitar player, and most of his records were of people like Django Reinhardt. I started playing the piano and the guitar around the same time, around age 13.

You see, I’ve always had different bands on different occasions long before I went into London to do it with professional interest. I had a band in Manchester, and when the R&B boom hit London, I moved there. I formed a band of London musicians, and it was just the same as usual. You ferret around to see who is available, and if anybody knows anybody who plays such and such an instrument. You get in touch with the musicians, report to the gig, and start playing.

I don’t try to explain that at all. Music knows no geographical boundaries. Records have always been the property of every country."

— John Mayall

When did you do your first recording?

The first album I made wasn’t released in the United States. They might release it again at some later date, because I’m no longer with that label, and the usual trick is to release everything you’ve got. It was done with Decca about a year before we did the record with Clapton, which is generally thought of to be the first album in the United States.

The one with Decca was a loser. It sold a thousand copies over one year — five hundred the first six months and five hundred and two the second six months. It was a live recording done at a place called Klooks Kleek, which was one of the places where I used to work when I first came to London. It was called John Mayall Plays John Mayall Live at Klooks Kleek, a very ungainly title.

How do you explain a young Englishman’s interest in blues even before it was appreciated on any scale in the country of its origin?

I don’t try to explain that at all. Music knows no geographical boundaries. Records have always been the property of every country. It is through records that you come into contact with music.

Why is it that Europeans, and particularly Englishmen, picked up the blues while the bulk of Americans weren’t even aware of the tradition of that form of American music?

That was always the case, and that is probably why the whole blues revival as such seemed to come from England. We never had the direct contact with the music as it was being played. We only had the records. As a result, Europeans are much more into record collecting and the research behind records. There is just greater interest over there.

This is a big place, and you tend to miss things that are on your own doorstep. French radio in particular has always had a lot of programs on jazz. An illustration is the fact that bluesmen like Memphis Slim have ended up living in France, because they were better received in Europe, and they actually could get work there. American Black blues singers have gone over there to get a name and then bounced back over here.

I remember reading the liner notes of the Crusade album. You made a plea for greater recognition of Black blues artists.

Yeah. That was primarily based upon the situation in England at that time. A great many of the bluesmen were being missed even though there are a lot of blues fans in the country, but individually they felt they were a minority group. They didn’t feel that they were being acknowledged as an audience by radio stations or the papers. They didn’t feel they were a large enough audience to make their point.

That over-exaggerated, inflammatory stuff was put on the back deliberately to get them to write into the musical papers and ask to hear more about “so and so.” They did that and people started to wake up until it reached the point where Melody Maker had a blues page every week.

You can’t just decide that people should like a particular guy; they just won’t. Everything really depends on the merits of the guy’s music."

— John Mayall

Do you think that circumstance has dealt a bad deal to American Black bluesmen?

You can say that. If you feel something for the music and your own particular favorites, you do tend to think they have had a bad deal. And a lot of them have.

But the thing I’ve learned is that you really can’t make anybody like someone. It’s a bit disheartening to realize that you can introduce somebody who you think is good, but if people won’t go to the clubs to support them and buy their records, even though they’ve had every chance, there is nothing you can do about it. What it means is that their music, their particular style, doesn’t appeal to as many people as you would like it to. You can’t just decide that people should like a particular guy; they just won’t. Everything really depends on the merits of the guy’s music.

Do you remember when black records were “race” records?

Oh yeah, up until the late '40s. You know the Presley era was really the start of the first black performers coming out — Little Richard, Fats Domino and the rest. You know that thing in part grew out of the Presley thing. He was influenced by Black records and Black artists and he even did their tunes, but people didn’t pay any attention to those records until the Presley thing.

Why is it that sometimes Black blues recordings are less exciting or less appealing than white, rock blues?

Because that in essence is what they do; that is them. There are exceptions like B.B. King, people who have a style of their own. But they themselves can limit their market if they don’t progress — if they don’t break away from doing the same old thing. Some of the Black blues players who have made it, say 10 or 15 years ago, play the same numbers that made them famous and think that doing that will make them a star forever. You have to change because the generations, the people who buy the records, turn over so fast.

Do you credit your survival in the business with the fact that you’ve been willing to change?

I don’t go along with the way the music business is —all the jive, the hype, and the commercial aspect of the thing. I can separate myself from it."

— John Mayall

Probably. It’s part of my character anyway. I don’t really like to do the same thing all the time. Besides, I don’t really consider myself to be a part of the music industry in certain respects. I don’t go along with the way the music business is —all the jive, the hype, and the commercial aspect of the thing. I don’t regard myself as being a part of that. I can separate myself from it and think how meaningless it is.

The structure of the rock business stinks. But most of the performers in the business seem to like it that way, and fair enough. That’s good for them. I’m not exactly an unknown when I come onstage, but I sort of inwardly treat the whole thing like that — that they haven’t heard me, and I’ve got to prove myself onstage from scratch. If you do make a name, when you walk out onstage you get a lot of appreciation, and half of the time they don’t understand what it is they’re supposed to appreciate.

But you’re supposed to be good, and that’s that. It’s a help in my case because it gives me the confidence to try something new, knowing that it won’t hit them that cold.

How did you run across Eric Clapton?

I hadn’t heard of him before we got together. You see, all bands in London are known to each other, but perhaps not the individuals that play in the bands. The Yardbirds were more popular on the club circuit than I was. They came up with a hit record, "For Your Love," which put them on the front page and the top of the charts. But it wasn’t a blues record that did it. Eric was working with them, and I guess wanted to stick to blues playing. The Yardbirds weren’t blues musicians as far as he was concerned. He got fed up and walked out on a big money-making thing.

Around the same time I heard that Yardbird record, and on the other side was a title called "Got to Hurry," with guitar by Eric Clapton. I was looking for a more satisfying guitarist, so I got his telephone number, and rang him up, and asked him to join. He said yes, and that was it. He was with me for nearly a year.

People who had heard of Cream then found about this other one. They bought it and probably became aware of me through Eric."

— John Mayall

You never made it to the States with Clapton, right?

Yeah, Peter Green was with me after Eric. The first time I came to this country was with Mick Taylor in 1968. The first time we played Winterland in San Francisco was with Albert King and Jimi Hendrix. The lineup of the band then was the same as on The Diary of a Band and Crusade albums, except without John McVie. What happened was that when we were over here for the first time, the Clapton album [1966's Blues Breakers With Eric Clapton] had just been released. There was a confusing time lapse of over a year. That album was released a year after he had left me, and he was already in the Cream by then. People who had heard of Cream then found about this other one. They bought it and probably became aware of me through Eric.

How do you feel about the Bluesbreakers With Eric Clapton album?

I feel about it like I feel about all the other albums. They’re just on wax or whatever. They’re just a representation of what the band was at the time. I like to listen to all of them. They all have good stuff on them. They show how the musicians played that I worked with, which is what I enjoy, otherwise they wouldn’t have been in the band.

Had Clapton reached a high point during the Bluesbreakers days?

He had reached a high point in comparison to his Yardbirds stuff. But I don’t think it’s anybody’s right to say that he is better or worse than what he did afterwards. It’s a matter of opinion. By the time he was finished with me he wasn’t playing very well at all, because he didn’t feel like it. He wanted to do something else. After a year with me he had developed his style to a point where he wanted to go still further but in another direction. His style was different with me than it was with the Cream, because he was responding to different sounds. He was influenced by different people.

That applies to most every musician. If you put them in with different people, they sound different because they’re playing different. The course of everyone’s development needs that. Otherwise, they go stagnant. I think that it’s really nice that you can get a musician who can be really satisfying in one band, and then he can develop in another band. You can hear another side of him. All good musicians are like that.

What do you think of the Eric Clapton album [Clapton’s 1970 self-titled debut featuring Delaney & Bonnie and Friends]?

To me it sounds like a Delaney and Bonnie album. That’s not to downgrade them; they do some nice things on records. And it’s not really surprising since Blind Faith was working with them. Even though the album is in his name, it’s really not his whole thing coming out. It’s got somebody else’s thing superimposed on it. He’s got a little outfit on the road now. And that’s the first time he’s taken it on his head to throw out all the superstar categories, get a band together, and play gigs for small money just for the sake of playing in small clubs. It is really commendable.

If you can’t hear who you want to listen to onstage, you don’t ask him to turn up; you ask everyone else to turn down. That way you get a listenable level."

— John Mayall

Clapton made the transition to a hard rock blues sound.

At that time Cream was totally original, so it was really an accomplished thing. But then everybody started to copy it, so everything you heard after that was a Cream copy. He couldn’t stand all that, being written about and everything.

Why didn’t you get into a harder sound?

I don’t want to get my ears blasted. I want to hear my musicians; I want to hear what they play. If you can’t hear who you want to listen to onstage, you don’t ask him to turn up; you ask everyone else to turn down. That way you get a listenable level. Just say that I didn’t want to join in. I took the risk and went the other way.

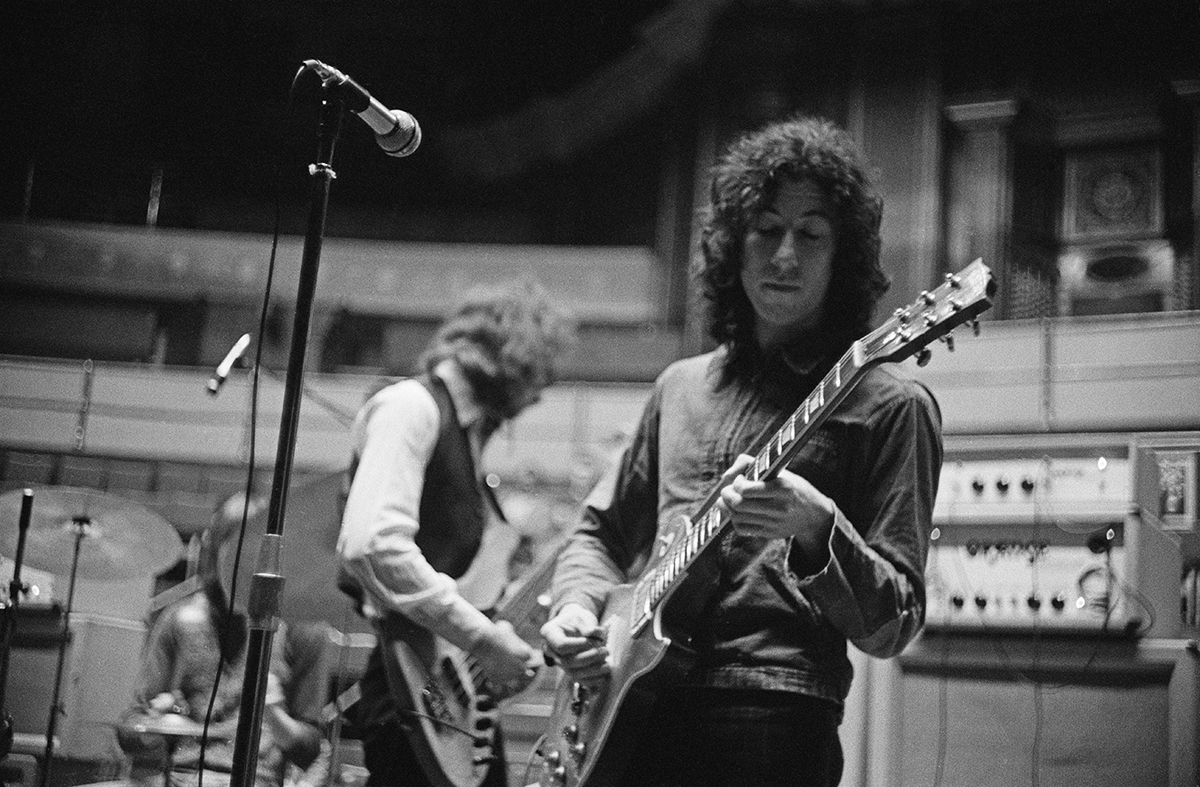

How did you run across Peter Green?

Peter is very funny. By the time Eric left we were getting known; the Clapton cult as such had started. So there were a lot of prospective guitarists. Actually, Eric left twice, so that was sort of a complication. He got the wanderlust. He went off to Greece with some friends of his to play over there. I had to find another guitar player. So I found one [Jeff Kribbett], and we were playing the same clubs, and it was known that Eric wasn’t with us anymore. The new guitarist wasn’t nearly as good, and he didn’t have that extra thing to make him a great guitarist.

Peter, this cockney kid, kept coming down to all the gigs and saying, “Hey, what are you doing with him; I’m much better than he is. Why don’t you let me play guitar for you. Why, he’s no good at all.” He got really nasty about it, so finally, I let him sit in. Peter worked about three gigs with me, and Eric came back. That really made Peter mad; he was just getting into it. Eric stayed another six months, and during that time Peter was in a band with Mick Fleetwood and Rod Stewart.

When Eric left again, I went straight away to Peter. But he didn’t really want to do it, because it had fallen through before. But eventually he did join. He really came in for a lot of bad things. At gigs people would say things like, "Where’s Clapton?" He had to have a lot of guts and determination to stick it out. He knew he wasn’t as good as Clapton, but he could be, you know.

How did Green happen to go his separate way?

The same way that everybody else did. They decide they’ve learned all they could or developed as far as they could in that structure, and it gives them the inspiration to take it further.

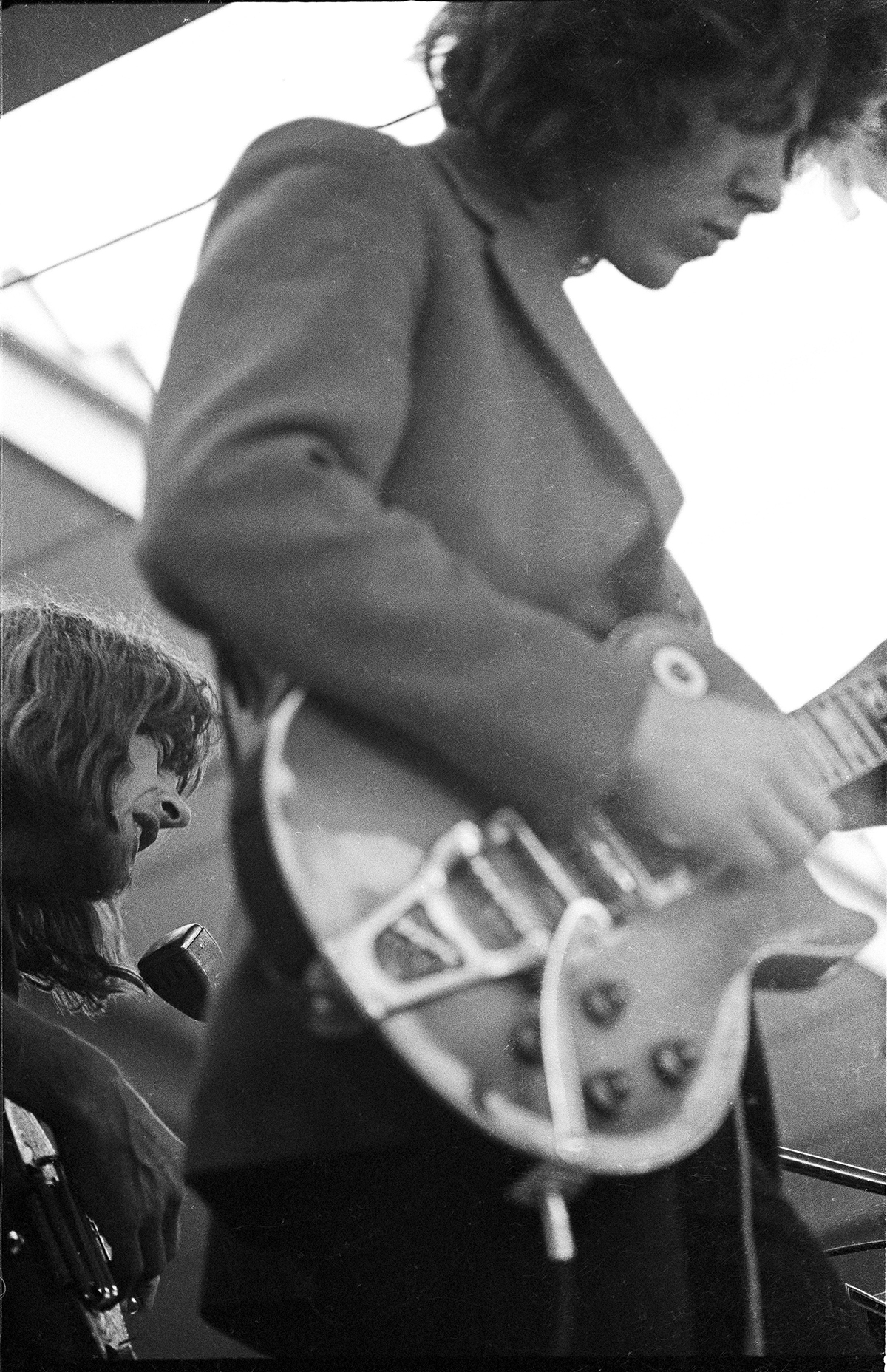

At that point, you found your third phenomenal guitarist, Mick Taylor.

Yeah, as it turned out. But at the time it really isn’t like that. You pick somebody you think is okay, and you go play clubs, and nobody pays much attention at first. It’s only a later turn of events that recognizes the talent there. The name comes later, and then it seems phenomenal that you could pick this winner out, you know.

Mick took a lot longer to develop his style than Eric or Peter. Mick is different than the two of them. Peter’s character is very pushy and he’s determined to prove himself. Mick was always a lazy person, not to knock him; he was just an easier-going personality. He took a lot longer to’ reach his peak, but he turned out to be phenomenal. [Like Clapton and Green before him, Taylor played a Les Paul Standard.]

What was it that you listened for when you first heard those three guitar players?

I don’t really know. I just need a guitarist, and I ask someone to do it in all good faith, hoping that they’ll be what I hope they will be. You put them in this loose environment, a very free thing where there are no arrangements and everybody gets to settle in and explore their own thing. Obviously, when you’re playing something different every night and it’s open to do that, then whoever it is is going to develop if he’s got the potential.

Did you direct them at all? Did you tell them what to play?

No more than I direct the musicians with me today. They look upon me as the bandleader, and it’s my responsibility if it goes wrong. They don’t have it hanging over their heads that it’s got to be good. All they’ve got to be concerned with is their own instrument. They’ve got this guy who points to them and says, “Okay, you take it.” And when they get that signal, they can do what they want. Then I’ll nod to someone else, or we will end it, or I’ll start singing.

So I have the control to direct a very loose thing. If something good happens that’s unexpected, or not what I meant, then I let it go that way. It’s really a nice surprise. On the other hand, if something is going on that is a total bore or a disaster, even though the audience might be liking it, then you bring it to a quick finish.

There are no arrangements of the tunes at all?

Not really, no. Sometimes there’s a theme. Mainly they know the key that I call out, and the kind of beat that it is. The tunes are all on a 12-bar structure so there’s no problem there. It’s just a case of how to end it. It doesn’t really matter as long as you play and people hear genuine music coming out. I don’t think audiences are really that much concerned whether it collapses in a disaster or not, as long as they know that you know that it’s a disaster and make the best of it. You know, take it or leave it, and they laugh, and we laugh, and that’s it.

Like in a set the other night, they all came off the stage saying that they thought so and so was supposed to do this and that. What happened was that one of the numbers —a 12-bar sequence —had a middle bit that was all one chord. To get back to the progression again, somebody has to lead it in with the preceding four bars. I was nodding over to Harvey and Larry, and Harvey took it to mean that I wanted him to solo. So it never got out of it, and Harvey’s solo was really good. I thought it was fantastic and we’d keep it going a bit longer because the audience didn’t know it was supposed to end there. Nobody knew because it was good.

Things like that happen all the time. That’s the interesting thing about it. From a situation like that you learn. Something that sounded good you will use the next time where it hadn’t occurred to you before it happened. There are no patterns; it changes all the time.

How committed are you to the blues?

All I’m committed to is playing what I want to play and making sure that it is different. I try to force myself into new areas that are a challenge. Blues is the only thing I know, so it would have to be through that.

Do you have any musical training?

No. I wish I could play musical instruments with a bit of technical ability sometimes. But I don’t think it’s really important. I can’t change it; I couldn’t learn music, you know. It’s the best that I can do, and the spirit is there.

From what you said earlier, you don’t seem to have much faith in the taste of audiences.

Oh, I do. What I said about audiences was that they don’t realize how unrehearsed and how dangerous it all is. They assume that what they’re hearing has been worked on and arranged. But actually it isn’t. I just get on the phone to somebody, and say that we start work on such and such a date, and I’ll see you at the gig. That’s all it is.

What about you as a guitarist? You’ve been playing a Gibson Les Paul. Is that your favorite guitar?

Well, no. I didn’t choose it. The guitar I had before that was a Fender, and it went out of tune. So I told my road manager to get me a new one. So he got me a Les Paul, because he could get one cheap or something. I don’t know anything about those things.

You don’t worry about strings and all that?

Just as long as they’re not rusty. If they’re rusty and you do a slide up the neck, you’ve got a torn finger. I don’t really worry about instruments, because they’re just tools. I’m not proficient enough on them to think that matters. Stick an axe in me hand and I’ll see what I can do with it. It’s as simple as that.

Fred Stuckey was a contributing editor to Guitar Player magazine in the publication's earliest years. During that time, he interviewed numerous guitarists, including John Mayall, Chuck Berry and Jerry Garcia, providing readers with their first in-depth articles about the players, their music and the gear behind it.