John Hiatt Talks Getting Back to Basics

The Grammy nominee explains how he likes to keep it lean and mean when it comes to songwriting and gear.

No one could ever accuse John Hiatt of being predictable with the music he makes. So it was completely in character that in the midst of his 30th anniversary tour for Slow Turning with the Goners, his original backing band, Hiatt took a sudden departure to make The Eclipse Sessions (his 2nd studio record) at a tiny recording studio in Franklin, Tennessee, owned by musician/producer Kevin McKendree.

The Eclipse Sessions was in progress when the total solar eclipse of August 21, 2017, plunged a swath of the country, including Franklin, some 20 miles south of Nashville, into darkness. Hiatt compares the album to a pair of his earlier releases, 1987’s Bring the Family and 2000’s Crossing Muddy Water. “They all had a vibe to them that was unexpected,” he explains. “I didn’t know where I was going when I started out on any of them, and each one wound up being a pleasant surprise.”

Supported by minimal instrumentation, The Eclipse Sessions’ songs emerge beautifully raw and emotive, as Hiatt’s powerful rhythm playing and gravelly voice bring uncanny life to tunes like “Robber’s Highway,” “All the Way to the River” and the tugging opener, “Cry to Me.” Rather than pull the Goners into the studio, as he did when recording Slow Turning decades earlier, Hiatt went with a different set of musicians for The Eclipse Sessions.

“I started the whole thing with those guys back in ’87, and it sort of defined me, in terms of the kind of music I was going to make,” he explains. “I felt the 30th anniversary of Slow Turning was closing the circle in a lot of ways. Not that it was ending something, but it was bringing it all full circle. Going back to Europe and bringing the Goners with me and playing those songs again, I felt that we’d ended a chapter.

“So, I had these new songs, and I was on to something else for the moment. [Goners drummer] Kenneth Blevins suggested I check out Kevin McKendree’s studio, which is south of Nashville in an outbuilding on his farm. Kevin plays keyboards with Delbert McClinton and Brian Setzer and some other people. So, we did four days there in August of 2017, and then we reconvened in October and spent four or five more days wrapping it up.”

These songs could have been presented any number of ways. So how did you choose the instrumentation?

I had told Kenneth that I didn’t know what kind of recording I wanted to make, and he asked if I wanted him to just play percussion and make it very minimal. So that’s where we started to get the idea of having him on a very broken-down kit, and I’d just play my acoustic and put it way up front, the idea being to just capture that and my vocal with some rhythm.

So, I played acoustic on my little ’54 Gibson LG-2, and Kenneth was on a kit that was just kick, snare, hi-hat and one mounted tom. Patrick O’Hearn played upright bass half the time and electric bass the other half, and it was just recorded as a live trio. We’d get a performance with the vocal, and that would be the take. It’s like we were catching some magic, and that’s all you’re trying to do when you record. Kevin and his 16-year-old son, Yates, were in the control room, and Yates would usually be engineering. Kevin oversaw the production, and he’d come out once we got a take and put piano or organ on it, and then we’d move on to the next song.

We cut three songs a day, and then we’d go home. At night, Yates would put lead guitar on the tracks. He did the acoustic slide part on “I Like the Odds of Loving You” and all the other solos, except for the one I did on “All the Way to the River.” I take a solo every once in a while.

Of all the guitar players you could have picked for this project, you gave the honors to a very talented teen. What’s the story on Yates?

Yates is an amazing musician. His parents bought him a drum kit when he was three, and Kenneth, who has been a friend of the McKendrees forever, started mentoring him on drums right away. Kenneth told me that Yates sat down and played a Texas shuffle first thing, and he played it perfectly. His dad also mentored him on keyboards, and he’s the youngest Hammond B3 endorsee. Yates has been playing guitar forever too, and when he plays on an electric, he frets with his thumb. It’s amazing what he does. He’s an old soul in a young kid’s body.

What guitar did you use on “All the Way to the River”?

That was a Fender Jazzmaster from the ’60s that I believe was Kevin’s dad’s guitar. It was a pretty badass one too. The whammy bar is what all that watery sound is on that solo.

I’m not sophisticated enough for pedals. I’d only get into trouble.

John Hiatt

Did you have a go-to amplifier?

I’m not all that particular about guitar amps. I like those little Fender 20-watt reissues for recording, and onstage I use a Swart amp. I like it a lot, and I use it with a power conditioner called a Brown Box by AmpRx. You plug it between the amp and the AC outlet, and it lets you set the voltage right in any venue. I think it makes a big difference in the sound of the amp. I know what I hear, and it does make a difference.

Are you ever tempted to plug into a pedal for a solo?

No, I’m not sophisticated enough for pedals. I’d only get into trouble.

Did you have all the songs completely worked out before going into the studio?

I never come to the studio unprepared. I’ve never winged it. I’m of the Guy Clark school. They ask him when it’s time to make a record, and he says, “When you’ve got 10 good songs.” That’s my formula too. If I came in without any songs, I’d feel like I was going to the doctor, where I’ve got to disrobe. It’s a form of disrobing. [laughs]

People ask me how I write songs and I tell them I have no idea. I don’t know where it comes from other than it comes out of the music.

John Hiatt

Is there any routine that you have for writing?

It’s taken so many different paths over the years, but in the main it just seems to happen when I pick up a guitar, so that’s kind of my routine. If I just pick it up and play, something usually happens that results in some kind of riff or chord pattern, and then maybe a melody will come out of that. And then I’m singing nonsense until some words or a phrase strike me.

Either the muse shows up or she doesn’t, you know? That’s kind of how it goes. People ask me how I write songs and I tell them I have no idea. I don’t know where it comes from other than it comes out of the music. But I usually don’t have lyrical ideas first. I’m musically inspired.

Are there certain guitars you’ve gravitated to for writing songs?

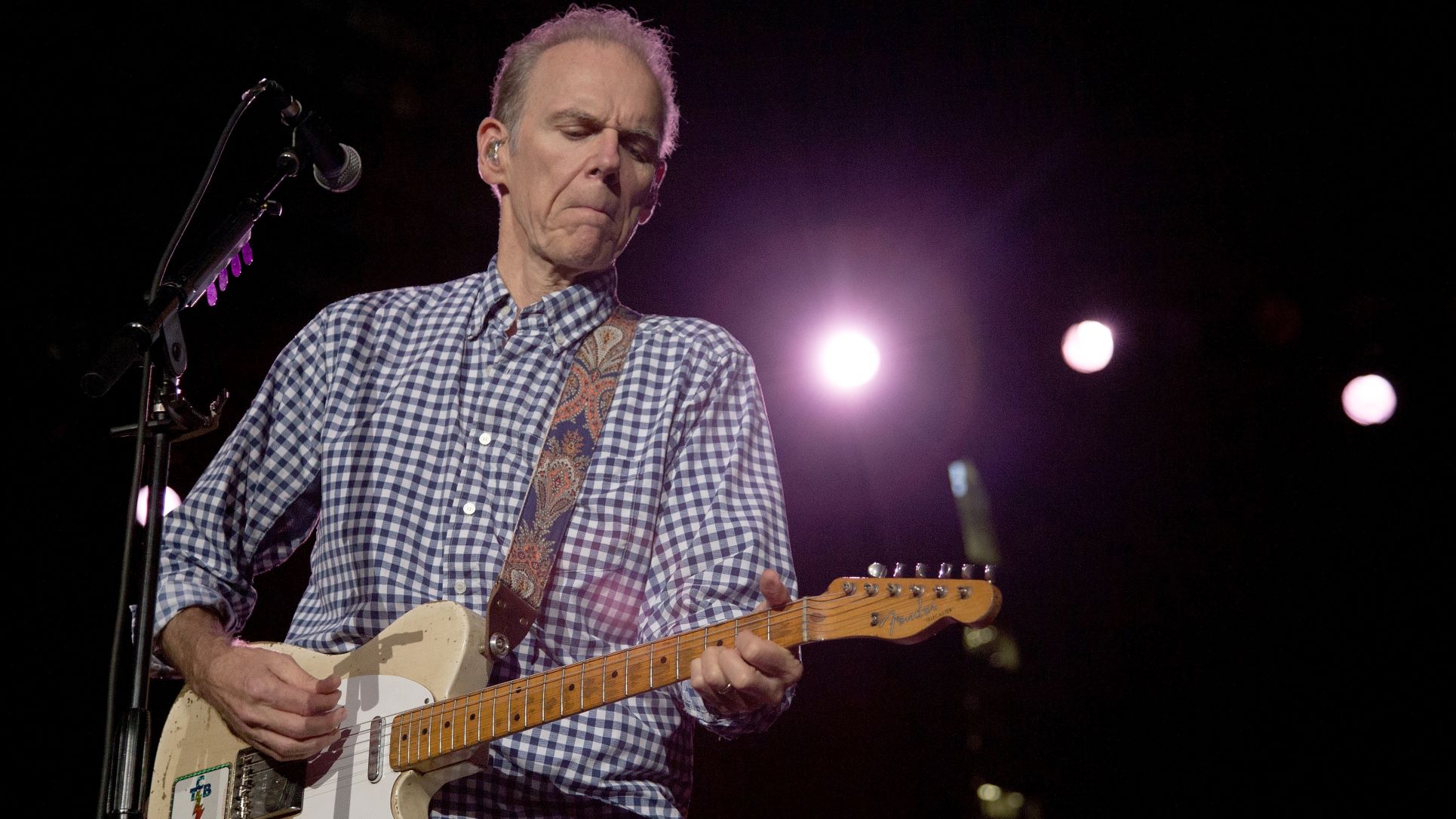

Well, Since about 1986 it’s been this little ’54 Gibson LG-2 that I bought off of a guy in Nashville. He wanted $800 for it, and I gave him $600. I’ve written so many songs on that acoustic guitar, and I even take it on the road with me. I used to not take it out, but then I just decided I love playing it and I love the way it sounds.

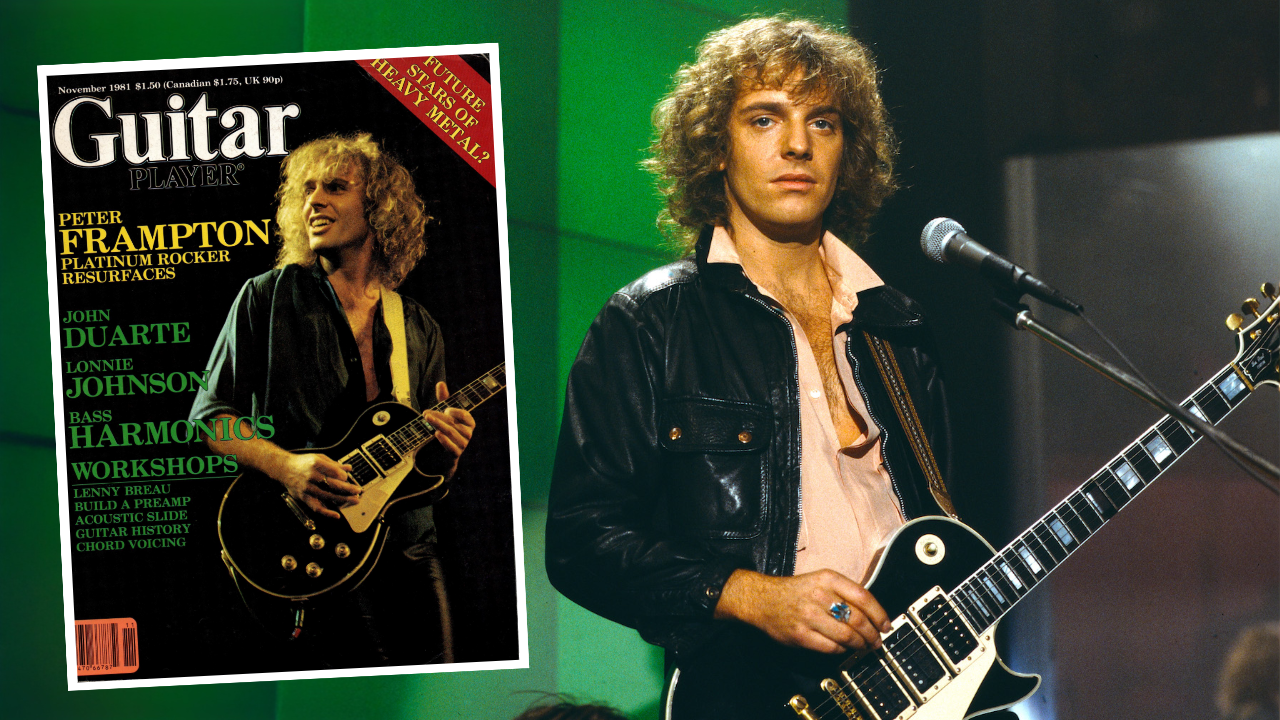

When I was making Riding with the King back in the early ’80s, we made half of it over in London with Nick Lowe and his band, and at the end of those sessions Nick gave me his ’57 Tele with a white ash body. I’ve had that thing ever since, and I love that guitar. So, it’s mainly those two, and they are the only cool old guitars that I have.

Everything else is like plywood Silvertones and stuff that I bought back when you could buy them for 50 bucks, before all the youngsters got a hold of them and drove the prices up. I’ve also got a Harmony, with a single pickup, that’s sort of shaped like a Les Paul, and it has a particular sound. Sometimes I’ll plug that into this little five-watt amp that breaks up in a certain way, and that’ll get something going.

I like it when a song can just stand on its own and get across.

John Hiatt

You were playing the LG-2 for the solo portion of your show on the Slow Turning 30th anniversary tour, and what impressed me was that, even with the Goners at the ready, you still take time to perform a full set by yourself. Can you talk about that?

I’ve done so much of it over the years, and I really enjoy playing solo. It’s just me and the limited scope of my guitar-playing ability and the song, and I like that. I can get a good rhythm going, and I like it when a song can just stand on its own and get across. It’s how the songs were written, and I think the audience appreciates hearing them in their original form. In fact, I’m on a 20-date solo tour right now.

In talking about how you structure songs, Sonny Landreth said in an interview: “It’s all about the raw emotion of the lyrics, because there’s not a set form. A good example is “Sometime Other Than Now” [from Slow Turning], which is all simple chords, but they change with the lyrics. A lot of pop songs sound like the words are written to fit a musical scheme, but with John’s songs, the lyrics come first, and the music supports that.” What do you think of that assessment?

That was a good observation by Sonny, because the changes do twist and turn in terms of, here’s where you thought it would go to the five [V] in a three-chord thing, but it hangs onto the four [IV] for a couple of extra bars or whatever. It’s kind of dictated by the story. I don’t think about it much, but I like it. To me, it’s what saves the three-chord thing from becoming mundane. You’ve got to put a little tweak in there somewhere.

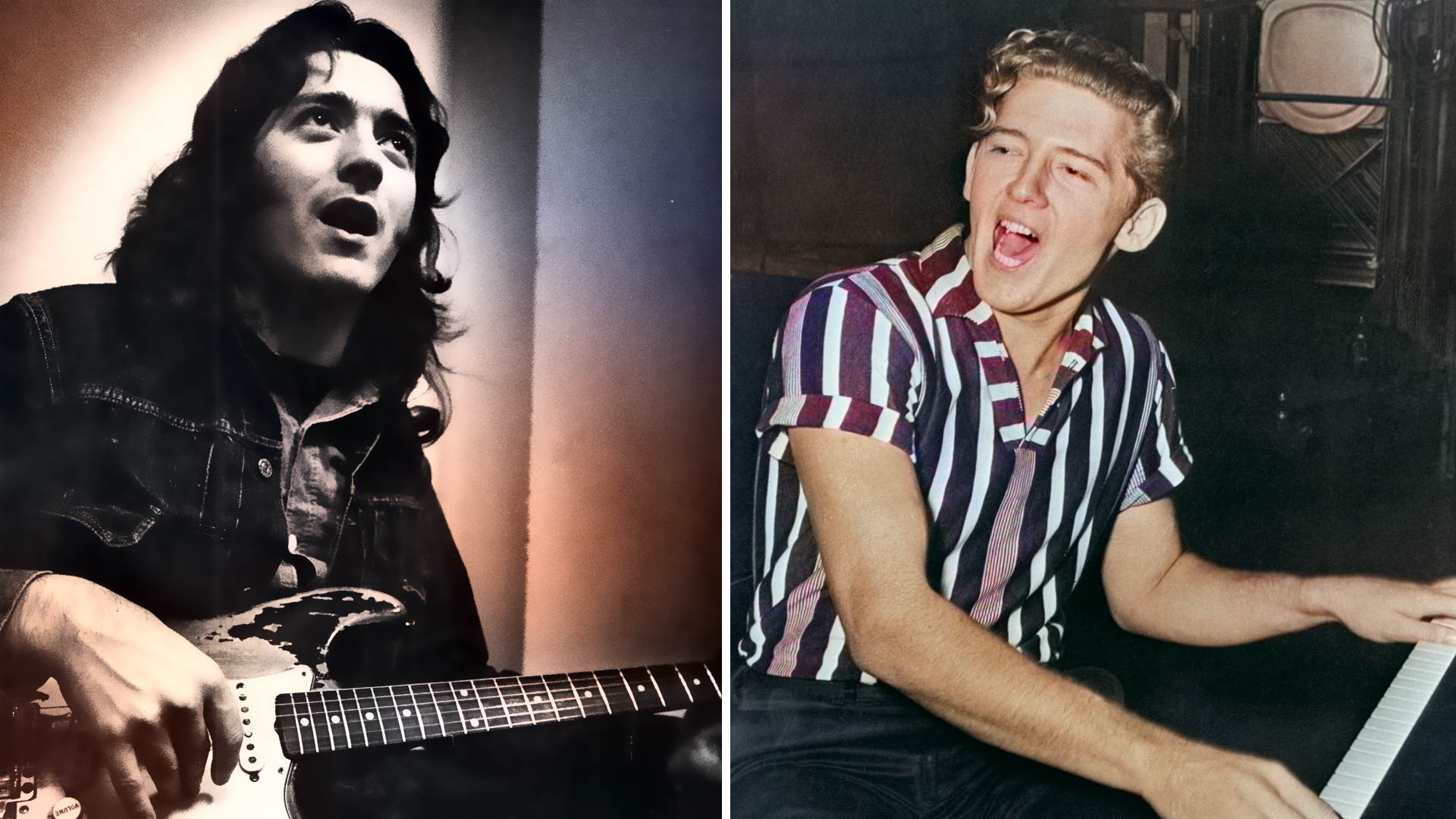

Ry Cooder used to tell me, “It’s like you get in a spaceship once you get a handle on an idea for a song, and you kinda take a little trip.” And that’s exactly what it’s like.

John Hiatt

Even though the lyrics come last, I write the lyrics as I’m playing, so that’s what happens. I get a little bit of a chord structure, and then I get a lyrical idea, and then the chords follow the lyrics. Ry Cooder used to tell me, “It’s like you get in a spaceship once you get a handle on an idea for a song, and you kinda take a little trip.” And that’s exactly what it’s like. I don’t necessarily know where it’s going to wind up until we get there.

What do think of the variety of artists that have covered your songs?

I’m really proud of that, because you don’t have to be this or that kind of artist to do my stuff. It seems to cut across all different styles. I’m proud that Iggy Pop and Paula Abdul have cut my songs. Or Willie Nelson and others that don’t seem to go together. That just has a lot of meaning to me.

Bob Dylan recorded “The Usual” and has done “Across the Borderline” live. So has Bruce Springsteen.

It’s an honor that some of my heroes would actually bother to sing one of my tunes. That’s the kind of shit when you’re growing up and think, Would I even entertain that notion? Would Eric Clapton or B.B. King do a song of mine? I mean, come on! [laughs] “Clapton is God.” That’s what I remember from my youth, not “Clapton is going to do one of your songs.” That’s pretty freaky.

Buy John Hiatt’s latest album with the Jerry Douglas Band – Leftover Feelings – here.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Art Thompson is Senior Editor of Guitar Player magazine. He has authored stories with numerous guitar greats including B.B. King, Prince and Scotty Moore and interviewed gear innovators such as Paul Reed Smith, Randall Smith and Gary Kramer. He also wrote the first book on vintage effects pedals, Stompbox. Art's busy performance schedule with three stylistically diverse groups provides ample opportunity to test-drive new guitars, amps and effects, many of which are featured in the pages of GP.