Like every other working musician on the planet, John Fogerty was forced to scrap most of his 2020 tour dates once the coronavirus pandemic hit. For his first few days of self-quarantine at home, the 75-year-old singer-songwriter and guitarist was content to bide his time – happy to indulge in a little unplanned vacation, in fact – but his wife, Julie, had other ideas.

“She said, ‘You should record something and put it online,’” Fogerty relates. “So I sort of grudgingly went along with it.” After filming a solo acoustic video of his classic Creedence Clearwater Revival hit “Have You Ever Seen the Rain,” Fogerty figured he could go back to hibernation.

That’s when Julie said, “Why don’t you get the kids involved?” This was an idea Fogerty immediately sparked to. His two sons, Shane and Tyler, both guitarists, perform together in their band, Hearty Har (Shane is also part of his father’s touring band), and his daughter, Kelsy, plays guitar as well.

Dubbed the Fogerty Family, the foursome pounced into activity, playing CCR gems on NPR’s Tiny Desk Concerts, taping a segment for The Colbert Report, debuting a SiriusXM show called The Fogerty Family Rockin’ Family Hour and releasing a string of pleasing videos on their own Fogerty’s Factory YouTube channel.

“It’s beyond an earthly delight,” Fogerty enthuses. “Just the fun of setting a song in motion, and then we get the rhythms going, and I get to perform these songs with my kids. It’s almost indescribable how wonderful the whole thing is. And to think it was sitting there under my nose all this time and I didn’t even know it.”

Fogerty’s Factory is also the name of the band’s recently released EP (among its seven tracks are versions of the CCR hits “Fortunate Son” and “Bad Moon Rising”), for which they re-created the iconic album cover of Cosmo’s Factory, Creedence Clearwater Revival’s celebrated 1970 album.

“That was Julie’s idea again,” Fogerty says, chuckling once more. “Lo and behold, she dragged in all this furniture, and then the motorcycle arrived. I looked at everything and said, ‘This is kind of cool. It looks like the cover of Cosmo’s Factory. I can go along with this.’”

I get to perform these songs with my kids. It’s almost indescribable how wonderful the whole thing is

For many fans, Cosmo’s Factory is the quintessential CCR album. Newly released in a 50th anniversary half-speed master vinyl edition, it’s the record that documents the band – Fogerty, rhythm guitarist Tom Fogerty, bassist Stu Cook and drummer Doug Clifford – operating at the peak of their powers.

“I would totally agree with that, because that’s what was in my mind at the time,” Fogerty says. “It was kind of the culmination – or the realization – of what I had always dreamed about. I worked hard at music, and we were having some luck. ‘Susie Q’ [the group’s 1968 single] was a hit, and there was an album, and then another album.

"We went to Europe and played the Royal Albert Hall. Finally, in 1970, I started thinking, Well, jeez, we’re getting really good and really popular. I kind of want to do a culmination of where we’re at, because I think we should evolve and kind of go on to something else.”

Packed with wall-to-wall smashes, including the double-sided hit singles “Travelin’ Band”/“Who’ll Stop the Rain” and “Up Around the Bend”/ “Run Through the Jungle,” Cosmo’s Factory is a remarkably diverse collection of styles, some experimental in nature.

There’s the loose Bakersfield shuffle of “Lookin’ Out My Back Door,” the elegiac soul balladry of “Long As I Can See the Light” and spirited takes on rockabilly and R&B covers – “Ooby Dooby” and “My Baby Left Me,” respectively.

And on two extended tracks – the orchestral rocker “Ramble Tamble” and a mesmerizing, 11-minute version of Marvin Gaye’s “I Heard It Through the Grapevine” – Fogerty distinguishes himself as a master guitar soloist on par with the celebrated six-string greats of the day.

Astonishingly, the album was the band’s fifth full-length release in a 24-month period, a time in which Fogerty had already penned the likes of “Proud Mary,” “Fortunate Son,” “Green River,” “Down on the Corner” and “Lodi.”

But the guitarist downplays the notion that coming up with the band’s original material – to say nothing of their hits – ever felt like a burden. “I never looked at it that way at all,” he says. “I was doing what I wanted to do, so it wasn’t hard.”

I don’t know if 'Cosmo's Factory' is perfect, but I never considered that I would want to change anything

He points to the writing of the band’s first original hit, “Proud Mary,” in 1968, as a moment of self-discovery, one that opened up the floodgates for his output.

“How do I say this? It was a vindication – a validation,” he says. “I had been watching other people’s careers, most notably Lennon and McCartney, but also Hoagy Carmichael and [Jerry] Leiber and [Mike] Stoller. What they did seemed so undoable, but when I wrote ‘Proud Mary,’ I realized that it was doable.

“I knew the song was a classic, so after that it became the idea of furthering that achievement. How do I push us even further toward the top of the mountain? And that’s what I kept trying to do.”

Indeed he did. The album’s title refers to the Berkeley, California, warehouse that served as the group’s rehearsal space early on. It’s there that Fogerty made them practice nearly every day, leading Clifford to dub it “the factory.” Clifford’s own nickname, Cosmo, would form half the name of CCR’s commercial zenith.

When asked if there is anything about Cosmo’s Factory that he wishes he had done differently, Fogerty laughs. “I don’t know if it’s perfect, but I never considered that I would want to change anything,” he remarks. “It’s a picture of where I was at the time, or where we were. My way of thinking was always, Okay, that’s there, but I’m just going to worry about what’s in the future. I’ll write another song.”

On Cosmo’s Factory, the band seemed to be getting away from the “swampy” sound of the earlier records. There’s raging rock, psychedelia, rockabilly, folk and R&B. Were you listening to all of those genres while you were writing these songs?

I listened to that all my life. I very much wanted that album to represent all of us, meaning all of what we knew. My musical interests were not necessarily the same as the other guys in the band. I think I had a much deeper knowledge of country music, let’s say.

Tom and I very much shared rhythm and blues and rock and roll, of course, and Doug and Stu were very much rock and roll – not so much stuff before that, meaning rhythm and blues or gospel. I had kind of been inspired by Tom and our older brother, Jim, because they were ahead of me.

I was probably eight when they were already listening to R&B. Rock and roll hadn’t been invented yet. So I kind of came upon Muddy Waters and gospel music pre-Elvis, and they were listening to that. Anyway, there’s a lot of diversity on the album. It sort of reflected the whole of what I had listened to.

In some ways, the album seems like the Beatles’ White Album in that, while there was growing tension in the band, you guys still managed to produce some of your best work.

I would agree with you. I’m trying to think of when the tension came to the fore. I can remember certain times when Tom would say something strange. It’s all hindsight today, but I realize now that Tom had some issues. I didn’t know it was jealousy – it hadn’t been formulated – but my wife, Julie, heard me talking about it and she said, “They were just jealous of you, John.”

Like I said, I hadn’t formulated it. It came from Tom – he would say these dark things once in a while, but Doug and Stu were a bit louder about it. They had this invisible bond. I was definitely aware of tension. I would hear people say things, but I adapted.

I would lower my head and be like, I didn’t hear that. There were times when I wanted to say something back, but if I had a cartoon bubble over my head, it would say, “I didn’t come here to fight. I came here to make a record.” My job was to figure out whatever I’ve got to do to make it.

We tend to focus on the drama around the time of Cosmo’s Factory, but were you guys still having fun?

Most of the time we were. Let’s face it: You’re standing on the stage at Albert Hall and you’re getting these encores, and that’s just a wonderful thing. Even checking in to a hotel, we were like, “Oh, my God. Did you see my room?!” There were fun times, absolutely.

We were on good terms. It started to change around the time of [the Cosmo’s Factory follow-up] Pendulum. It’s just a simple thing of, yes, I could be a tyrant, a dictator. I was that guy yelling, “Follow me, boys! We’re going up the hill!”

I couldn’t entertain a side variation for very long, because it wasn’t taking us over the hill. The journey to success is always the most fun. It starts to erode as you accomplish your goals. As you get to the two-yard line, things become more difficult.

But I don’t want to focus on negative things. It’s just not on my radar anymore. It is what it is. My job was to be like the quarterback, and I could see that. At the same time, I was very much a team player. Even naming the album Cosmo’s Factory. We literally referred to the place where we rehearsed as “the Factory,” but calling the album that was my little attempt to make Doug famous.

Certainly, the album cover conveys the idea that you guys were enjoying yourselves. It’s a fun cover.

I asked the guys to bring to some of their favorite things, with no qualifications: “We’ll arrange everything in our factory.” I thought it was fun, but some people thought it was clunky. I had this nagging idea to present ourselves as being normal. I didn’t want us to seem arrogant. I hate that.

Like CCR’s other albums, Cosmo’s Factory had double-sided hits – “Travelin’ Band” and “Who’ll Stop the Rain”; “Up Around the Bend” and “Run Through the Jungle.” Was it a problem to decide on the A-sides?

I think there were times while I was making the songs, I certainly knew what I thought the A-side was. Starting with “Proud Mary,” I had made up my mind that I wasn’t going to have an ordinary band. I wanted to have the greatest band there ever was, so I insisted on going with the best music. That was my commitment. Other bands would put album cuts or filler on the B-sides.

I didn’t want to do that. I wanted to put out the very best. I’d waited my whole life to have a career. This wasn’t my career; this was our career. I was like the coach of the team, or whatever, and I was doing everything I could to make our team – our band that I believed in – everything it could be. I was using all of it, the best of it. I wasn’t holding anything back.

Did you have any kind of roadmap for arranging your guitar parts? The midsection of “Ramble Tamble” is like orchestral guitar.

What I did was make a literal roadmap, as if you were starting in California and you’re going to drive to South Carolina. I remember taping a whole bunch of pieces of binder paper together with Scotch tape. As I say, I started in California and I went from left to right. A lot of it was more mental, although I probably had a few days, if not a week’s worth, of jamming with the fellas.

Then I was back home, and I probably had my Rickenbacker in hand, working out the parts: “Okay, we’ll do this, and then there will be a little solo here, and then we’ll come back and do another verse. Okay, what are we going to do here? Oh, I like that thing I was doing where I went to D and G. Yeah, that’s cool.” So I would write all of that down to help guide me.

When you were cutting the track, were you conducting the guys?

Kind of. I always did that. There were always a lot of head shakes and shoulder moves. With a real band, back in the day at least, one of the things you had as your fingerprint was dynamics.

You could get louder and softer, and hit a certain phrase harder and then back off for things that came later. Those are nuances. Those are things that happen when you’re all there together, and you’re going to do this right as it’s happening. It’s just the coolest thing.

Was it loud in the room? It sounds as if it was.

Absolutely, yeah, because I was using those Kustom amps. It was rockin’. It was loud enough that we couldn’t have talked to each other, and they couldn’t hear me singing. By the way, we tended to learn most the songs as instrumentals, and therefore I wasn’t singing at the same time I was playing. We learned “Up Around the Bend” as an instrumental.

Let me ask you about the riff to that song, which is such a cool, hair-raising opener. How did that come about?

I had always loved the lick in the [Marty Robbins] song “A White Sport Coat (and a Pink Carnation).” There’s also “You’re So Fine” by the Falcons, which had a similar kind of lick. I know I would play that from time to time, or the lick from “White Sport Coat.”

And then one day I was in just the right mood, and I was playing it but doing it in a different way. I hit the A string and let it resonate. It sounded really cool, and I thought, What would it sound like if I tried it in a different key? And I was like, Hey, that’s awesome!

“Lookin’ Out My Back Door” was your tribute to the Bakersfield sound.

Yeah. I had a Gibson J-200 acoustic. I had bought it because it was big – I wanted a dreadnought. I’m pretty sure that’s the guitar I used for the scratching on that song.

It was a tribute to the Bakersfield sound, but it was more a tribute to a sort of country-style rock and roll. I do love Buck Owens, and I was a fan of Don Rich. He played such great guitar on all of Buck’s records. I considered him country, but I didn’t consider me country.

Were you surprised when people said you had written a drug song?

Yeah. Even though I was young and considered myself a hippie, I wasn’t a real hippie. The song was supposed to be a kid’s song, kind of like Dr. Seuss. I remember reading a review that said, “You know what he means by ‘dancing on the lawn’? That’s his coded way of saying ‘grass.’” I read that and went, What?

And the flying spoon was supposed to be a cocaine spoon.

I just pictured a tablespoon with wings on it, like it was flying in the sky. I didn’t know what drug you would take with a spoon. I really didn’t. I was just thinking like a kid.

I remember reading a review that said, “You know what he means by ‘dancing on the lawn’? That’s his coded way of saying ‘grass.’” I read that and went, What?

You mentioned how the band would learn some songs as instrumentals. Did you not have words at the time?

Sometimes, sometimes not. Sometimes I couldn’t even tell them the title of a song. I believe it was “Up Around the Bend” and “Run Through the Jungle”: We were leaving for Europe on a Tuesday, so I had to go home on a Friday and write the words to both songs so that I could record all the vocals and backgrounds on Monday. And I had to overdub any other parts. I had to do all that so we could send it off as a single. There was a lot of pressure.

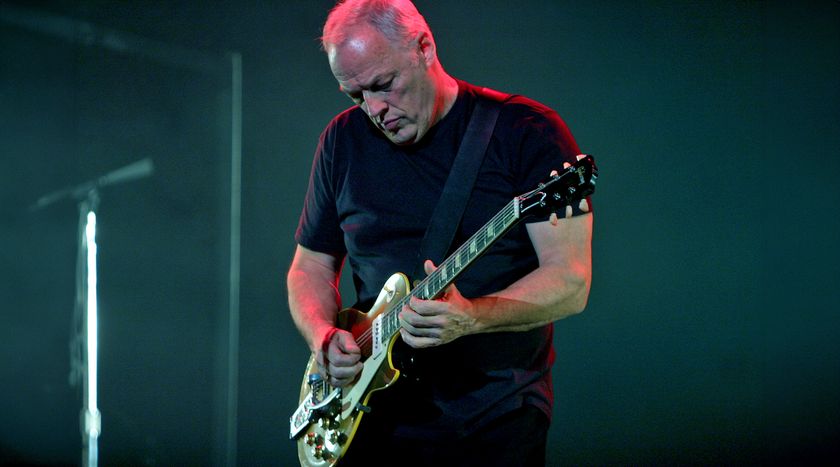

Throughout the CCR years, you were using Rickenbackers and Les Pauls – you had your black ’68 Les Paul Custom. Are those the main guitars you played on Cosmo’s Factory?

Yeah, other than the acoustic J-200. A lot of the time I didn’t even have a backup guitar. When I recorded “Proud Mary,” I had a Gibson ES-175 – I wanted an acoustic-electric sound. That guitar got stolen out of a car, so I had an emergency, because we were going to record “Bad Moon Rising.” I started thinking about Les Pauls because I had a Les Paul pickup on my Rickenbacker.

So I went to this guitar store run by a fella named Jimmy Luttrell, and I said, “Do you have any Les Pauls?” He pointed to this black Les Paul Custom. So I tuned it down and plugged into a Fender Twin, and I strummed a chord. I’m sure my eyes crossed with ecstasy: That’s it! That sound!

Those big Kustom amps on the album cover – you were one of the few guys using them.

I might have been the only one. It’s kind of funny, because I would get a handful of letters from people over the years, saying, “Hey, John, I went and bought a Kustom amp just to be like you. [sourly] Thanks.” It wasn’t a compliment. Mine was a ’68, what they call a K200. It had a tremolo/vibrato circuit, which was magnificent.

You could blend them. I thought that was unbelievably beautiful. It had reverb on it, but I never used that, because when the reverb was on, the volume of your guitar went down. Besides the tremolo/vibrato, the best thing about the amp was its harmonic clipper. It had a fuzz tone that really worked. Maybe I just got the best amp of the batch. I had a backup that was a little inferior to the one that was my main rig.

The amps did look pretty cool, with that Tuck ’n’ Roll Naugahyde covering.

And the sound of the box was big. They had 15-inch speakers. Every other lead guitar player was using 12-inch speakers, which are great, but the 15-inch had its own thing. When I played a D chord on my black Les Paul into the vibrato of my Kustom, the sound out of those 15-inch speakers was absolute heaven. I mean, you couldn’t match it. You have to have every ingredient to make that sound.

When people talk about guitar heroes, they mention Jimmy Page, Jeff Beck and Eric Clapton, and, of course, Hendrix. But your playing on “I Heard It Through the Grapevine,” or even earlier on “Susie Q,” ranks right up with those guys.

You know, I thought I could play pretty well, but at some point after our big success, I began to realize there was some things I couldn’t do. Among my generation, Clapton, Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page are often mentioned as the three greatest guitar players of their time, and I’ve always thought so too.

I greatly admired them. And obviously there’s Jimi Hendrix, who was probably the best of all. No one could even get near him as a guitar player. He was like Zeus on Mount Olympus.

I thought I was a hotshot, but I never put myself in their league. I knew I wasn’t as good as James Burton. And I have to mention Chet Atkins, whom I considered the greatest guitar player in the world.

I wanted to grow up and be as good as him, but I knew I couldn’t. And, of course, my rock and roll idol was Duane Eddy. I knew I couldn’t do anything like what Les Paul or any jazz guy was doing. I didn’t want to be Les Paul or Johnny Smith. That stuff is so good and well done, you almost don’t even think a human did it.

I remember one time I was in the studio with Gerry McGee, from the Ventures – a super guitar player. I told him about the solo in “Grapevine” and how I played the whole thing in the same position. I never even moved up and down the neck. He looked at me and said, “Well, we all thought you were pretty damn good!” [laughs]

- Creedence Clearwater Revival's Chronicle: The 20 Greatest Hits, is available for preorder.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

"Jaco thought he was gonna die that day in the control room of CBS! Tony was furious." John McLaughlin on Jaco Pastorius, Tony Williams, and the short and tumultuous reign of the Trio of Doom

“It’s all been building up to 8 p.m. when the lights go down and the crowd roars.” Tommy Emmanuel shares his gig-day guitar routine, from sun-up to show time