“I took a bass string, put it on the guitar, and tuned it in unison an octave lower than the A string so I'd still be able to play with all six strings.” Joe Perry reveals his unusual techniques behind writing classic Aerosmith riffs

The guitarist shares stories on the making of "Walk This Way," "Back in the Saddle." "Same Old Song and Dance" and more

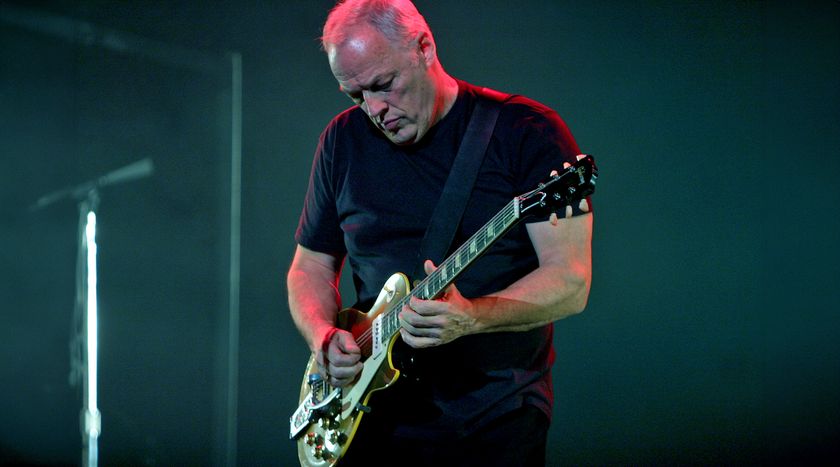

Having authored some of the finest and sleaziest riffs in rock history, Joe Perry knows a thing or two about what it takes to make those riffs stick.

Be it "Walk This Way," "Combination," "Fever" or his solo riffs, like "Mercy" or "Let the Music Do the Talking," which Aerosmith later re-recorded, Perry has his riff-writing process dialed in, with step one centering around letting go.

"You have to cut your thinking," Perry tells GP. "You have to let the thinking part of your brain loose and let your subconscious take over. It's an exercise in getting a connection to your heart and soul, and sometimes, these riffs just come out."

Perry has written the riffs you know and love at soundchecks in Hawaii and while sitting on a 4x12 amp as it was about to be loaded into a truck. It all goes to prove that you have to be ready when inspiration strikes.

"You don't really know where they come from," Perry admits. "Sometimes, you sit down to write a song, and you don't feel like playing. You're not particularly inspir, but you never know what's going to inspire you. You're fired up some days, and sometimes, you're not feeling it. That's the creative process.

"It's a puzzle," he continues. "You're always trying to figure out what makes one song sound like magic and another one not so much. But you've just gotta do it. You can't sit around and wait for inspiration. You've got to make your own luck."

Judging by Perry's body of work, it really doesn't matter where the riff for, say, "Same Old Song and Dance" came from, just that it did. It's the same with all of his iconic work, and so it shall be until he writes his last riff.

"With riffs," Perry says. "They're little bits of magic. There was nothing, and then there was something. Those little bits of magic… I don't know where they come from, man. Since the beginning of time, people have been trying to figure that out."

"Same Old Song and Dance" (1974)

Steven and I were really starting to learn how to write together. A lot of the songs from the first album were songs he had with his other bands. He had a notebook full of stuff, and some of the songs didn't have music to them but had some chord charges, like "S.O.S. (Too Bad)." That song already had lyrics, and Steven had the changes.

But a lot of the music from those first couple of records, like "Same Old Song and Dance" — like how we wrote in those days was Steven would be playing drums, his main instrument, and he'd have the microphone sitting there. We would jam along, and I tended to write riffs that were kind of melodic, and "Same Old Song and Dance" was like that.

We were jamming along, I played a riff, and Steven said, "Play that again." We hit "record" on the tape player for a second, played it a few more times, and it became the melody for the song. That's one of a bunch of songs that came about that way.

Basically, it was the foundation for how we were going to work together as songwriters. That song really jumps out at me. It's not a complicated riff by any means, but it's got a kind of hooky thing. That's what it's all about.

"Walk This Way" (1975)

In the '70s, we were either on the road or in the studio — and we were on the road. Once in a while, we'd take a week or two off, but most of the time, we were working. We were in Hawaii and knew we were going into the studio and gathering songs.

We were well into the part of our career where we wrote songs and some stuff in the studio. After the first two records, which had songs that we basically played in clubs, we used up all of them. So, I was thinking of some of the funk that I really liked and thought, "Let's see if we can get something that's got that kind of groove."

We were in soundcheck in Hawaii, and I asked Joey [Kramer] to just play straight, funky twos and fours while I started working on a riff. The first part was basically the verse, and then, you need a place to go, and I changed from down to the E chord from a C. Every chord change needed a little signature to it, like a little bit of a riff.

By the time I finished the soundcheck, I pretty much had all the parts. Then, Steven [Tyler] heard what I was playing as he came in and asked Joey if he could sit down and play the drums. I don't really remember who came up with the [opening drum] riff; that's between them, but I got what I needed, and that's all I was looking for.

When we recorded it, Steven was still looking for the hook. We were upstairs at the Record Plant and needed a break. It was in the evening; the guys went to see Young Frankenstein. I didn't feel like going, but when they came back, they were laughing and joking about the old Groucho Marx line, "Walk this way," like an old vaudeville thing, and Steven said, "Okay… walk this way. I think that's what I needed."

They took it and left for about two hours, and when he came back, he had pretty much all the lyrics. And then, we pretty much laid the song own. I remember using a Strat, and I would bet it was a 50-watt Marshall 4x 12, just straight in.

"Toys in the Attic" (1975)

We were getting ready to go to New York to record at The Record Plant, and we had a good bunch of songs and enough to go in. We finished rehearsing up in Boston, and the guys were pulling some gear out, you know, Marshalls and stuff. We were sitting around, talking, and they were breaking the gear down, and [producer] Jack Douglas said, "We need one more rocker. We need a barnburner."

So, I said on one of the 4x12s, and just started jamming a little bit. And after a couple of minutes, I had that beginning riff from "Toys in the Attic." I said, "I kind of like that," and again, you need a place to go, and that's when I came up with the riff for the vocal, so I had those two parts. The next time the band got together, we worked it out. Everybody threw down, and it became "Toys in the Attic."

I might have been playing a [Gibson Les Paul] Junior at that point. I don't think it was a Les Paul. It might have been a Junior with a P90. That's the one I was playing a lot when the riff came about. But a lot of these riffs, on a lot of these guitars, you know, anybody that writes music will tell you that stuff just comes out, and you don't know where it came from. I've had that feeling a lot.

"Back in the Saddle” (1976)

I've mentioned a thousand times that one of the biggest influences on me has been Peter Green with Fleetwood Mac. We used to cover some of those songs; I must have seen him eight or nine times when they played in Boston. I'd seen them every time they'd come through; I'd see him every chance I got.

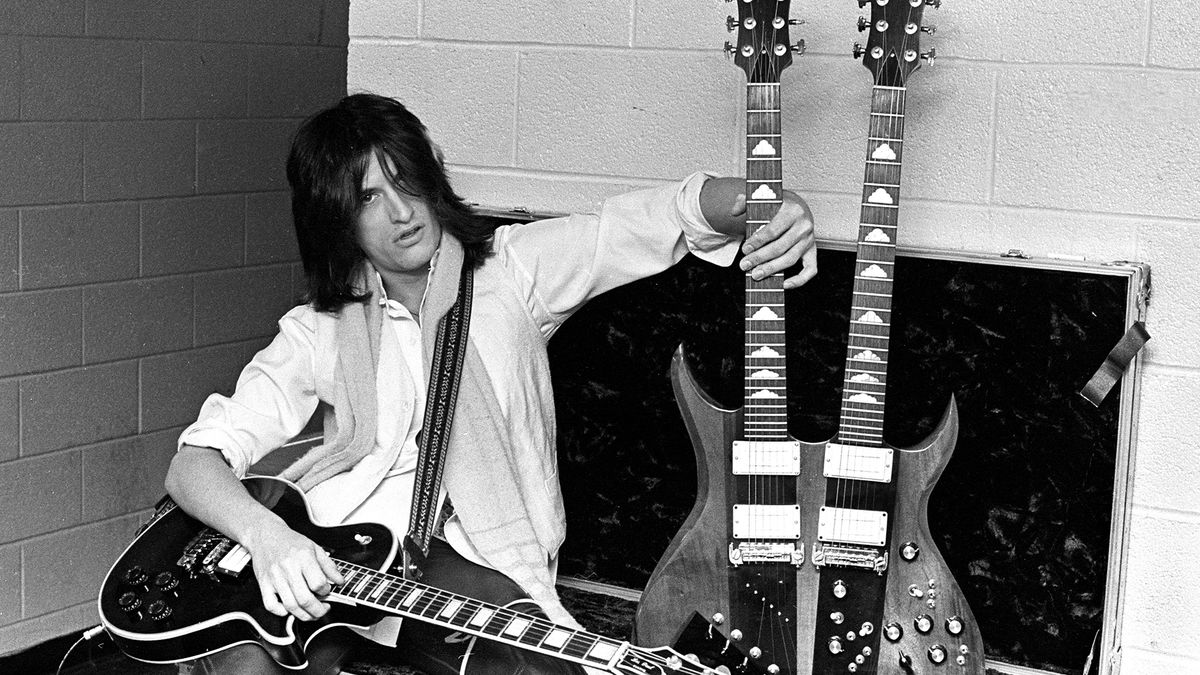

One of the things I know that Peter would do during their jams — and they did a fair amount of jamming — is he would give his roadie his Les Paul, and he would pick up a six-string bass. I'd never seen a six-string bass before, and at that point, I didn't know that Jack Bruce used one in Cream sometimes. I'd never seen or heard one.

But Peter Green used to jam with one, and it was a cool sound. So, when I started making a little money, I went out and bought one and started fooling around with it. I said, "I gotta play this, man. I need an excuse to play this." [laughs] I started fooling around with these riffs that sounded cool on the six-string bass, and you could get some nice vibrato out of it.

So, I worked up this riff and was lying on my back in my rehearsal room, just jamming on it. And once you get a riff, you need a place to go, so I recorded it with a cassette player, brought it to the band, and we jammed on it. That's "Back in the Saddle." I believe that almost every guitar you pick has a song in there, even if it's one I've never used.

I've used that six-string bass a lot, but that's the only song I've ever written around it. And I'd like to think it was the inspiration for that song in Spinal Tap when they had three guys playing bass. I think the song is called "Big Bottom, and they had a bass player, a middle bass, and a lead bass, or whatever. I saw the movie and it was like, "Well, yeah, I can relate to that." [laughs]

"Let the Music Do the Talking" (1980)

I have to include this one because I like to talk about the open tuning, you know, the classic Robert Johnson G or A tuning. I wrote a lot of songs using that tuning, but I didn't want to sound like Keith Richards, so I had to work around that, though it's pretty easy to hit some chords… I mean, so many Stones songs are written around that tuning; it's genius.

Anyway, I really like that tuning. I heard here that Keith liked to take the low E string off, so he had just five strings, which made it easier to play bar chords up and down the neck and not have to worry about the E string getting in the way. But I was thinking, "Well, that's kind of a waste of a good tuning peg," so I took a bass string, put it on the guitar, and tuned it in unison, only an octave lower on the A string, so I'd still be able to play with all six strings.

It really sounds pretty amazing; I sat down and wrote some riffs and a lot of songs around that, like "Let the Music Do the Talking," I had that riff for Aerosmith, but by the time I'd left [in 1979], it had never gotten on the list. When I left, we were working on Night in the Ruts, and I left before it was done, but we had most of the music recorded.

So, "Let the Music Do the Talking" was one of the riffs I had lying around, and it was one of the first ones I worked on for my first solo album. I used that open tuning, and the name of the song says a lot about how I feel about letting the business overtake us and why I left the band. There was too much politics, and I just wanted to get away from it and take a break.

But when I got back to Aerosmith [in 1984], and we were talking about doing a new record [Done with Mirrors], Steven liked the riff enough, and the rest of the guys were like, "Let's go with that one." Steven rewrote the lyrics, and when we played it… it was a little funkier on my solo record. I had a different grind and groove, but it's the same riff. I love playing that one.

I probably used my clear-body [Ampeg] Damn Armstrong with that bass string added to it. And I would bet that I was using a Marshall Plexi, but it's hard to say because I had two Hi-Watts, some Fender combos, and a blackface Twin going at that same time.

"Nine Lives" (1997)

When we first cut the song "Nine Lives" down in Florida, we worked with Glenn Ballard, who had just done that Alanis Morissette record [Jagged Little Pill], which was climbing the charts. The way we recorded was really different than usual, and when the record company heard it, they felt that it didn't sound like us, you know?

The point is that the songs weren't working. It just didn't sound right. So, we switched producers and worked with Kevin Shirley. His nickname is ‘The Caveman.’ He's Australian, tough, and old-school analog. Everything was played live, and we had the songs down really solid. We weren't too excited to recut everything, but we understood because the record didn't sound like it should have.

We had all the amps in a row and set up to play live. We had enough separation so we could play live, but we still overdubbed. It was a 180-degree difference in how we were recording, and the song "Nine Live" didn't really have a beginning worked out; it was just kind of a count-off at that point.

So, one of my favorite rock songs ever, which still gives me goosebumps when I hear it, is "Stroll On" by The Yardbirds. It's one of the few recordings that has Jimmy Page and Jeff Beck on it, and at the beginning, Jimmy and Jeff are both getting feedback… I could listen to that 10 times in a row, and it still sounds like the first time I heard it.

I was thinking about that, so rather than count "Nine Lives" off, I didn't say anything; I just hit that first note while standing in front of the amp and let it feedback. Brad [Whitford] did the same thing, and that's the beginning of that song.

Maybe it's not what you call a "riff," but for me, it's one of the best ways to start a song, and it's one of my favorite guitar things that I've done. It was right off the top, the tape was rolling, and we didn't rehearse it. That's what Aerosmith is about, you know?

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

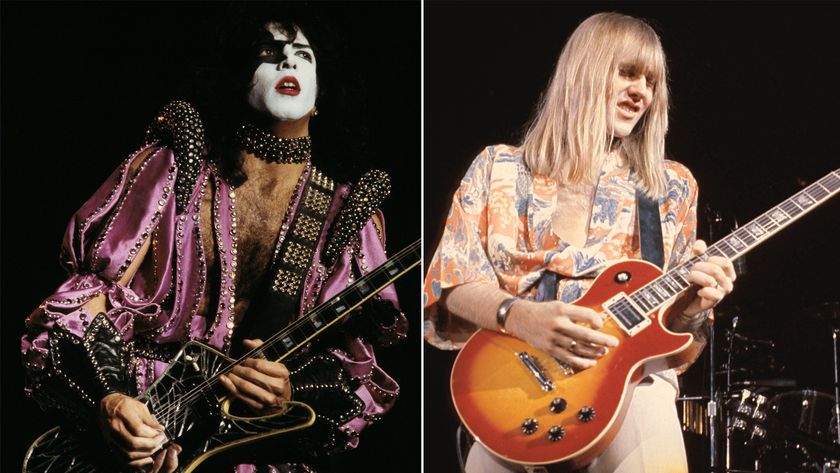

Andrew Daly is an iced-coffee-addicted, oddball Telecaster-playing, alfredo pasta-loving journalist from Long Island, NY, who, in addition to being a contributing writer for Guitar World, scribes for Rock Candy, Bass Player, Total Guitar, and Classic Rock History. Andrew has interviewed favorites like Ace Frehley, Johnny Marr, Vito Bratta, Bruce Kulick, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Rich Robinson, and Paul Stanley, while his all-time favorite (rhythm player), Keith Richards, continues to elude him.

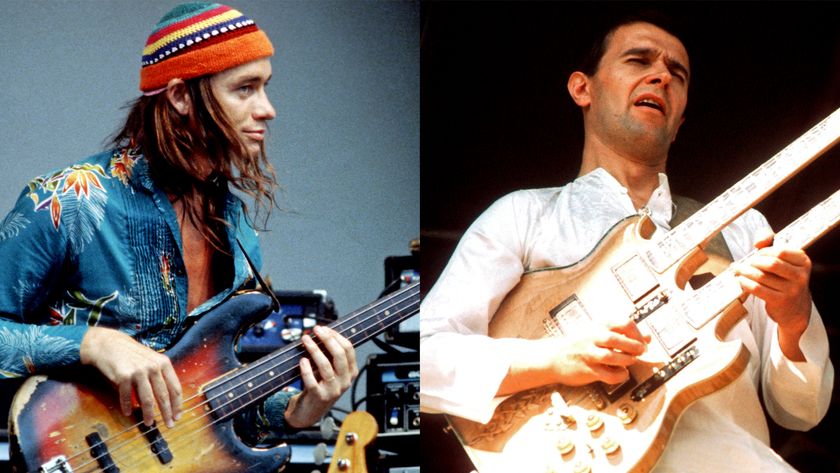

"Jaco thought he was gonna die that day in the control room of CBS! Tony was furious." John McLaughlin on Jaco Pastorius, Tony Williams, and the short and tumultuous reign of the Trio of Doom

“It’s all been building up to 8 p.m. when the lights go down and the crowd roars.” Tommy Emmanuel shares his gig-day guitar routine, from sun-up to show time