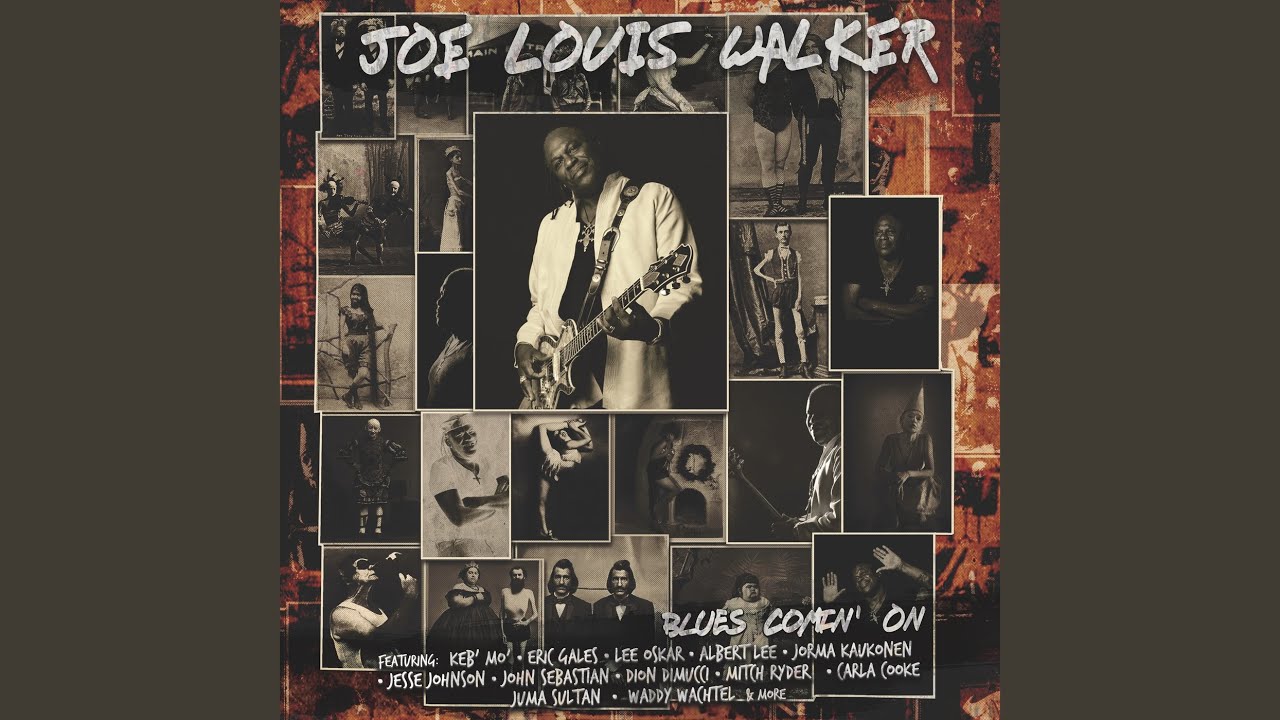

Joe Louis Walker on Following His Own Blues Path and Finding Joy in Letting His Collaborators Take the Spotlight

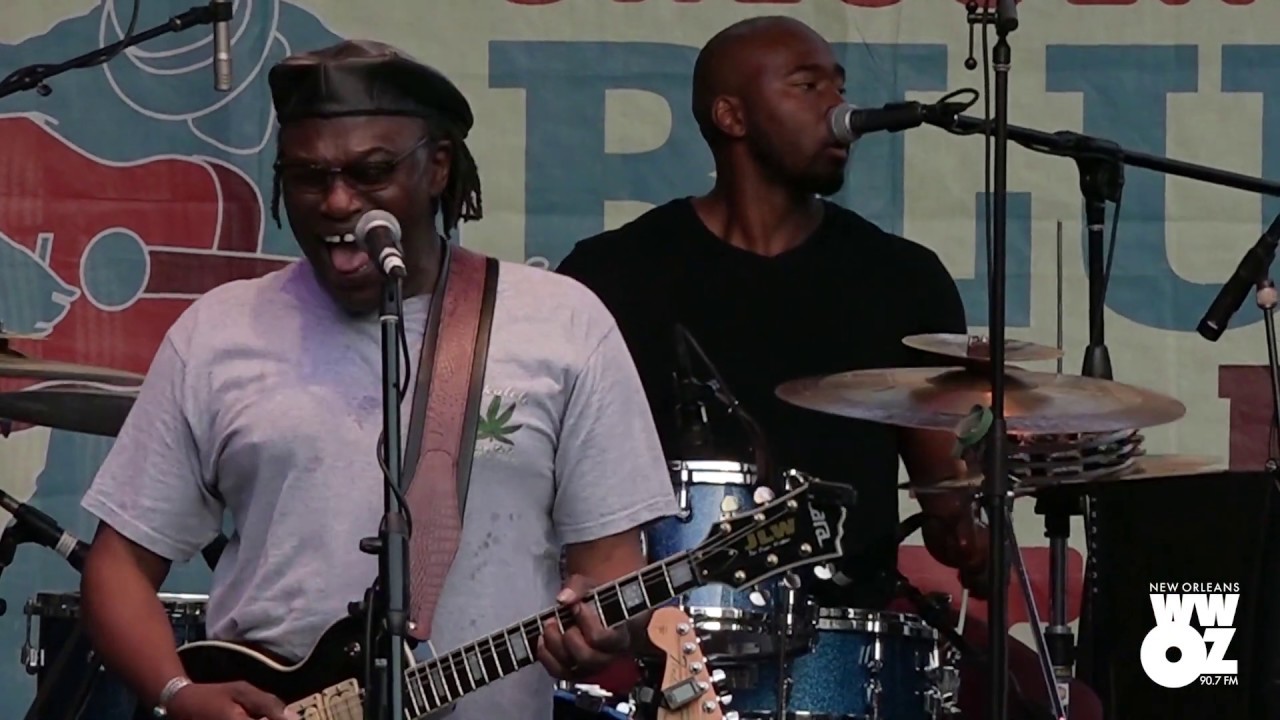

Joe Louis Walker connects with a cast of great guest guitarists for 'Blues Comin’ On.'

“I’m a fan of guitar playing, but I am more a fan of the diversity of guitar playing and different styles,” Joe Louis Walker says of his latest release, Blues Comin’ On (Provogue/Mascot).

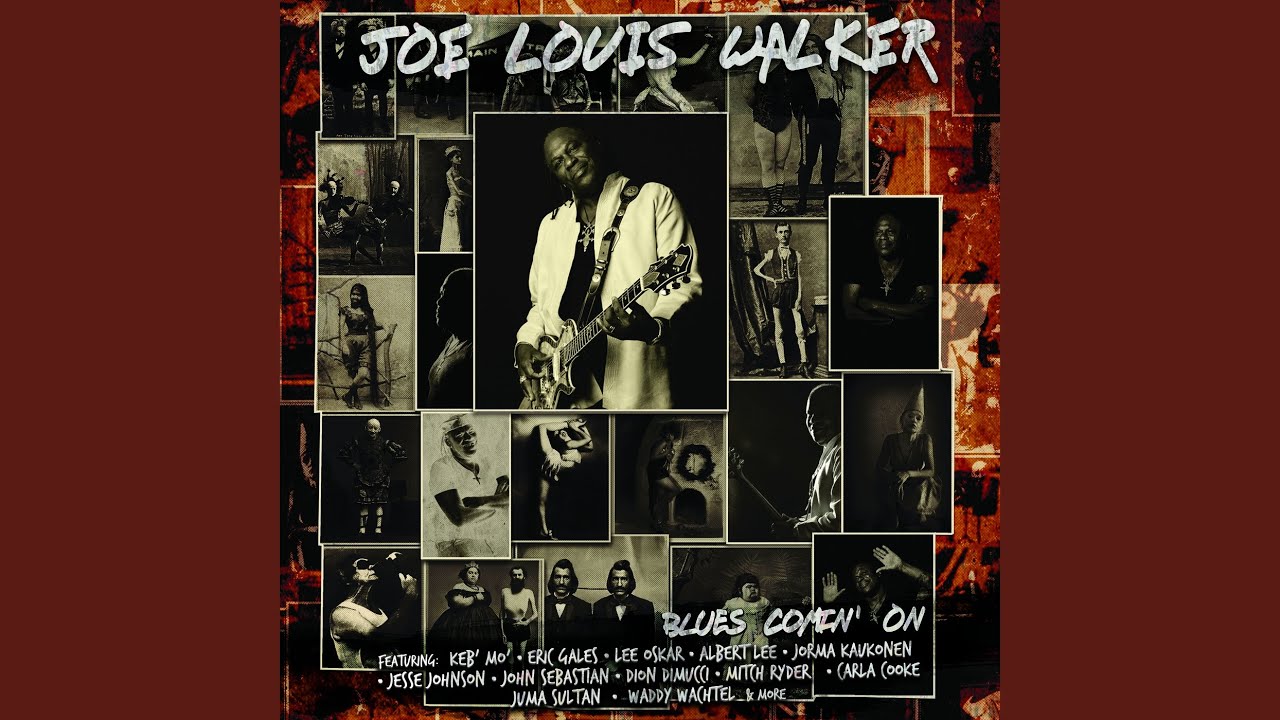

Diversity is the key word, and Walker has built his reputation for pushing the boundaries of blues with his powerful playing and soulful vocals during a career that has spanned more than 50 years.

He picked up the guitar at 14 and within two years was performing in and around his hometown of San Francisco, where he befriended blues icon Mike Bloomfield, who introduced him to Jimi Hendrix and the Grateful Dead.

But in 1975, Walker exited the blues scene and for the next 10 years sang in a gospel group called the Spiritual Corinthians. When the group performed at the Jazz & Heritage Festival in New Orleans in 1985, Walker was inspired to get back to blues, and formed the Boss Talkers, a band that gave him a platform to meld soul, gospel, funk and rock influences with his blues sensibilities.

Released in 1986, Cold Is the Night was followed by a slew of releases throughout the ’90s that led to collaborations with artists such as James Cotton, Buddy Guy, Branford Marsalis, Bonnie Raitt, Taj Mahal, Ike Turner, Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown and Tower of Power.

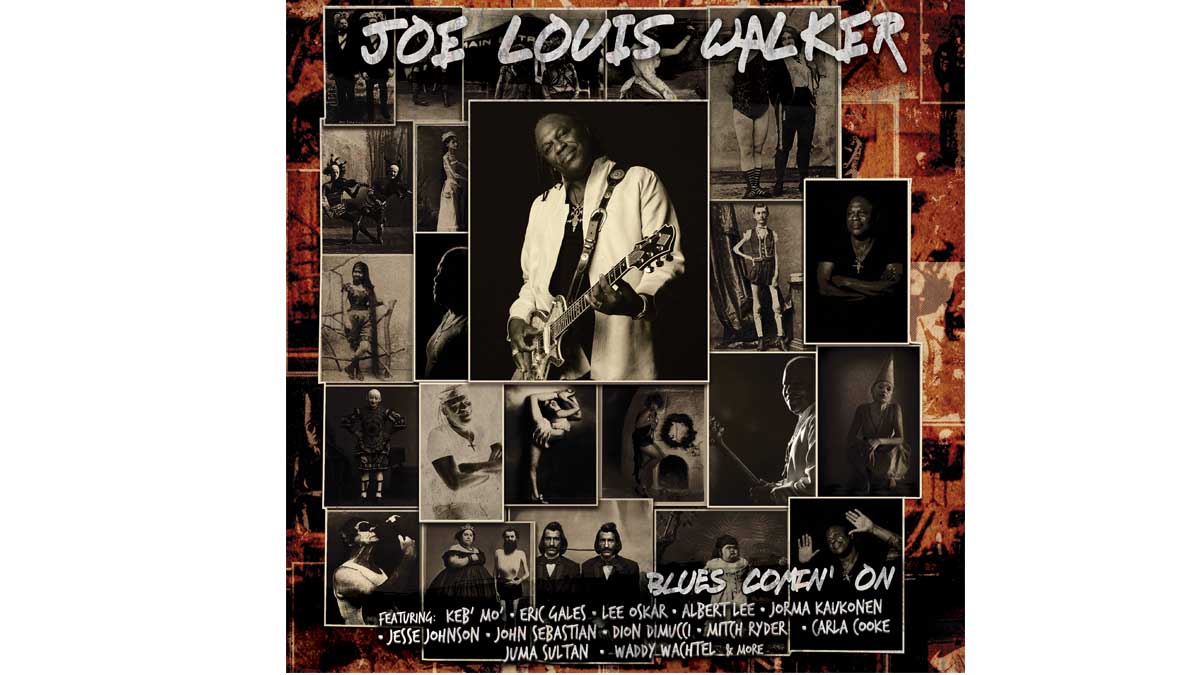

A four-time Blues Music Award winner and Blues Hall of Fame inductee, Walker is joined by a cast of top-tier musicians on Blues Comin’ On, which he produced and recorded at NRS Studios in Catskill, New York.

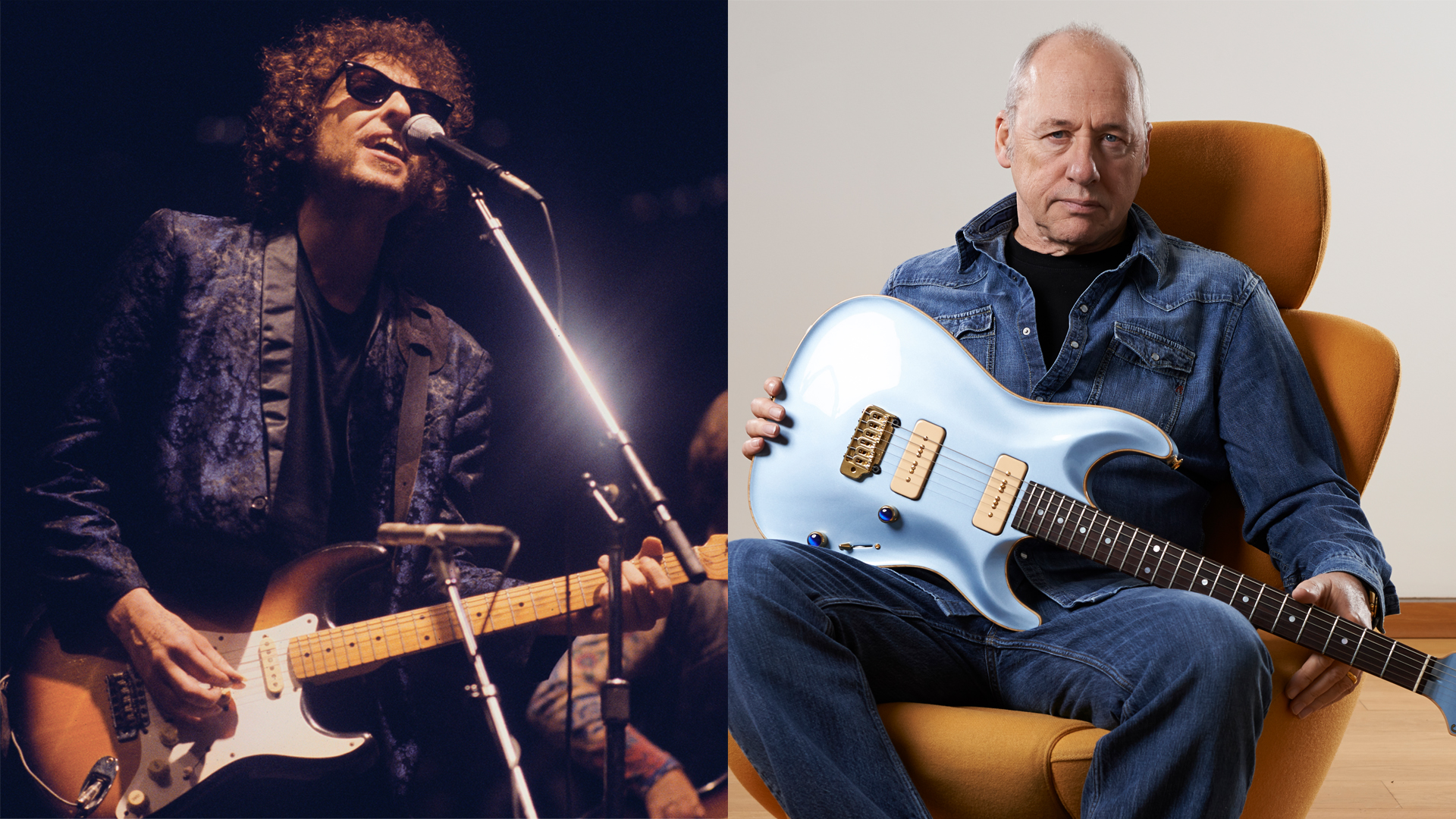

It features performances by Jorma Kaukonen, Eric Gales, Keb’ Mo’, Dion, John Sebastian, David Bromberg, Waddy Wachtel, Arlen Roth, Albert Lee, Jesse Johnson and Jellybean Johnson of the Time - as well as Detroit soul singer Mitch Ryder, harmonica wizard Lee Oskar, Carla Cooke (daughter of Sam Cooke) and punk legend Charlie Harper.

The music is as varied as one might expect, as it travels from blues rockers like the Dion-penned title track and “Feed the Poor” (which Walker co-wrote with Gabriel Jagger), to the powerhouse funk of “Uptown in Harlem” and “The Thang,” to the stompin’ “Old Time Used to Be” and a sweaty rendition of the Bobby Rush classic “Bowlegged Woman,” which features ripping lead work by Wachtel.

Characteristically, Walker gives the other six-stringers on this album the lion’s share of the solo spots. In fact, he didn’t play lead at all on the record.

“I like it because I don’t have to be the guitar star,” he explains. “When you have someone like Eric Gales, and you’ve got Waddy Wachtel and Albert Lee and Jesse Johnson, you get so many takes on the music. It makes me feel good to create a song that lays a platform for them to just take off.”

How you did you wind up up working with Jorma Kaukonen on “Feed the Poor”?

I was thinking, Who would be the perfect person to play on that song?, and Jorma was the obvious choice, because we come out of that generation. We had to wait a couple of years to get Jorma to come in to the studio, because he’s pretty busy. But I wanted him because his choice of notes is different from anybody’s.

Like, when you hear “White Rabbit” and “Somebody to Love,” they sound great, but then you hear what Jorma plays and it sounds extra great because it draws you in and is so iconic. The cool thing is he’s the same guy I used to see playing the Fillmore [Auditorium] when I was 17.

What can you tell us about the title track with Eric Gales?

I’ve known Eric since he was about 16, and the thing about him that is so spectacular is he’s the closest line I can draw to Jimi Hendrix. Eric can play blues, he can play somewhat outside, he’s not hampered by scales, and he’s also got that sort of classical influence in his playing, which is the movement of notes.

You could hear it in Jimi Hendrix with songs like “Burning of the Midnight Lamp,” where there’s all this movement, and it’s definitely classical. [sings the intro melody] If you put a hundred guitar players in a room, maybe one could do that kind of movement and write a song and have all this imagery. That’s something from a higher power, and Eric Gales is like that.

You didn’t play any guitar solos on this record. Why is that?

I like songs more than I like to wank off on the guitar. I can appreciate jam bands and all that, but if you go back to older blues, like Muddy Waters or B.B. King, there’s one guitar solo. It’s straight to the point and out. Same with the Rolling Stones. You can stretch out onstage, but the song is what you are serving.

I do stretch out once in a while, but I’ve made more records where I played lead on just two or three songs. I like to give homage to the guitar, and it’s what I can express myself the most on, but I don’t have to use it all the time, and I’m not one of those guys where I’m playing to go, “Hey, everyone look at me!”

Jesse Johnson is so funky on “The Thang,” and then you Hendrix-ize it.

Yeah, I got a chance to pay homage to the left-handed guy with that “Manic Depression”–style riff at the end of that song. I like those cool little funky riffs Jesse plays when I’m singing, and then he comes out like a house on fire.

I played it for Waddy, and he goes, “Holy crap, look out below!” I knew Jesse could play, but I didn’t know how good he is. It’s like that song is tailor-made for him. I wrote it in 1984, and it’s taken this long to record it.

And then you’ve got Jellybean Johnson on “Uptown to Harlem.” Everybody knows Jellybean as the drummer for the Time, but he’s also the guitarist on Alexander O’Neal’s stuff, and he is a wicked player. The original “Uptown” by the Chambers Brothers didn’t have a guitar solo, so we let Jellybean go, and he created another space.

How did you work out the acoustic arrangement with Keb’ Mo’ on “Old Time Used to Be”?

Keb’ is playing the resonator and I’m playing 12-string acoustic. Those are the only guitars on there because I wanted to leave room for Bruce Katz to play piano. Bruce has played with everybody, and he’s a national treasure.

It also really worked having John Sebastian on harmonica. In fact, the whole thing started off with me and John because he doesn’t live that far from me. I enjoy John’s company, and he’s another one of my heroes.

What kind of 12-string do you play?

I’ve got an old Yamaha, and I played it on “Feed the Poor” and “Lonely Weekends.” If I’m playing harmonica or playing with another guitar player and they want to pick on the single strings, I like to hold the rhythm down with a 12-string.

• “Feed the Poor”

• “Blues Comin’ On”

• “The Thang”

• “Old Time Used to Be”

• “Seven More Years”

• “Uptown in Harlem”

I usually play with my fingers because it’s easier to keep the rhythm going. Waddy’s also layering acoustics, so there’s acoustic guitar all over this record. I also have a 12-string Martin that I have to go pick up. I’m looking forward to getting my hands on it.

What electrics are you using?

I mostly play Zemaitis guitars, and I’ve got a pearl-front and another that looks like a Firebird. They’ve got some balls to them. And I like those Dragon pickups - they kick ass. As for amps, I’ve got an old Gibsonette, and I have a DV Mark Little 250.

It’s got headroom galore and a sweet tone. I use it onstage sometimes, and sometimes I’ll take my RedPlate, which has a Dumble sound that’s really great. I’ve got two of the Joe Louis Walker models.

Do you think that different guitars affect how you play?

I never thought a guitar was going to make me sound a certain way. I make it sound a certain way. I just think it’s a tool. You can get an old Strat that’s all beat up like Stevie Ray Vaughan’s, but you ain’t going to sound like Stevie Ray. And you can get a B.B. King Lucille, and you ain’t going to sound like B.B.

I’ve been to B.B.’s house, and there were Telecasters, Broadcasters, Gold Tops. And he sounded like B.B. King on all of them. [laughs]

Can you offer any advice for blues guitarists coming up?

My whole thing with the blues is, number one, the music is about credibility. You don’t have to rewrite the I-IV-V, but you can mix it up.

Every blues guy who helped me - whether it was Willie Dixon, who helped me write songs, or B.B. King, Earl Hooker, John Lee Hooker or Mike Bloomfield - all of them would say, “Do it your way, not our way. Don’t try to act like you are Elmore James in 1965. Do it like Joe Louis Walker.”

That has always stuck with me. You may catch some lumps for not being status quo, but if you’re just one of the pack, you’re going to sound like one of the pack.

- Joe Louis Walker's new album, Blues Comin' On, is out now via Provogue/Mascot.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Art Thompson is Senior Editor of Guitar Player magazine. He has authored stories with numerous guitar greats including B.B. King, Prince and Scotty Moore and interviewed gear innovators such as Paul Reed Smith, Randall Smith and Gary Kramer. He also wrote the first book on vintage effects pedals, Stompbox. Art's busy performance schedule with three stylistically diverse groups provides ample opportunity to test-drive new guitars, amps and effects, many of which are featured in the pages of GP.

"This 'Bohemian Rhapsody' will be hard to beat in the years to come! I'm awestruck.” Brian May makes a surprise appearance at Coachella to perform Queen's hit with Benson Boone

“We’re Liverpool boys, and they say Liverpool is the capital of Ireland.” Paul McCartney explains how the Beatles introduced harmonized guitar leads to rock and roll with one remarkable song