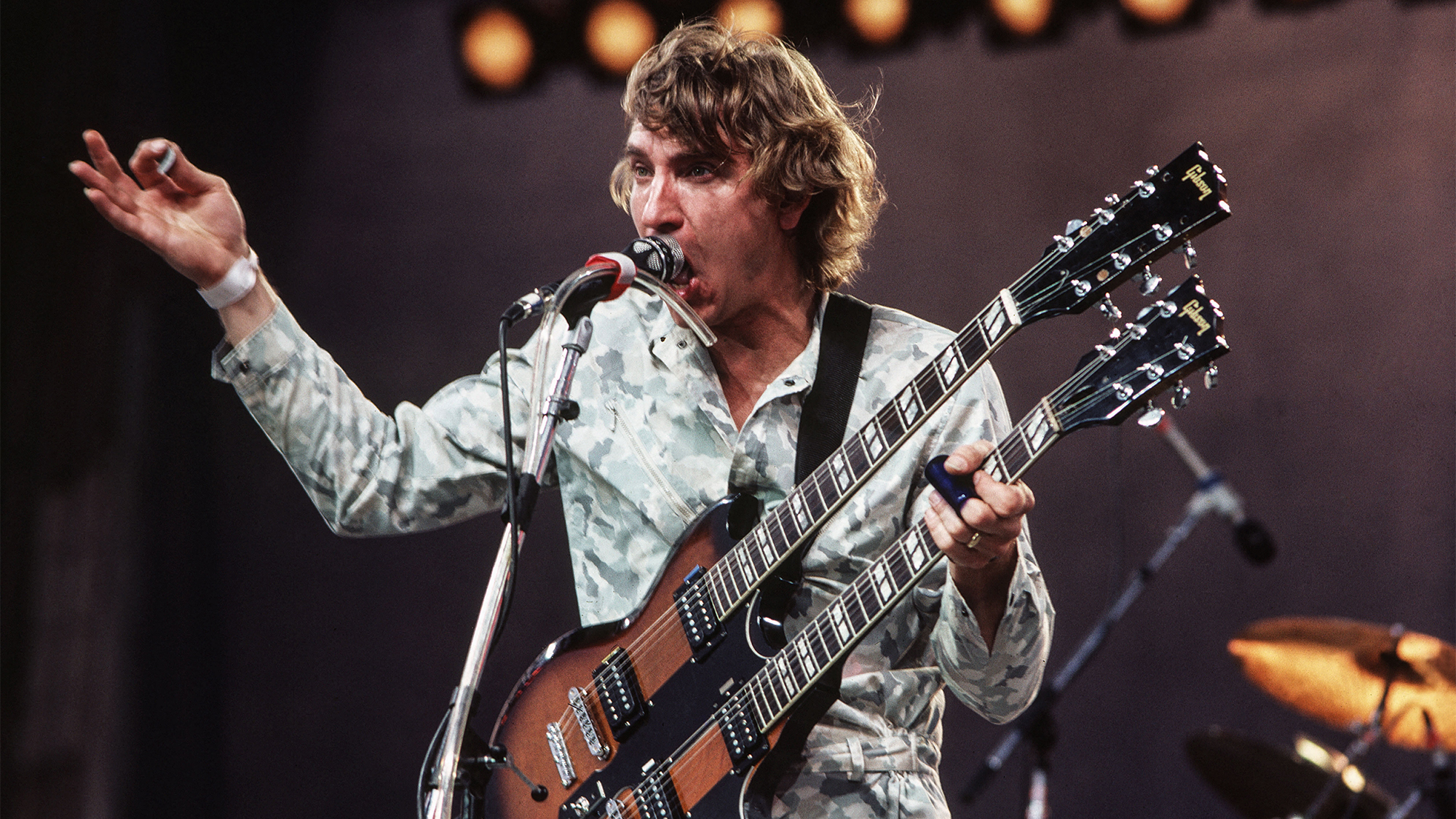

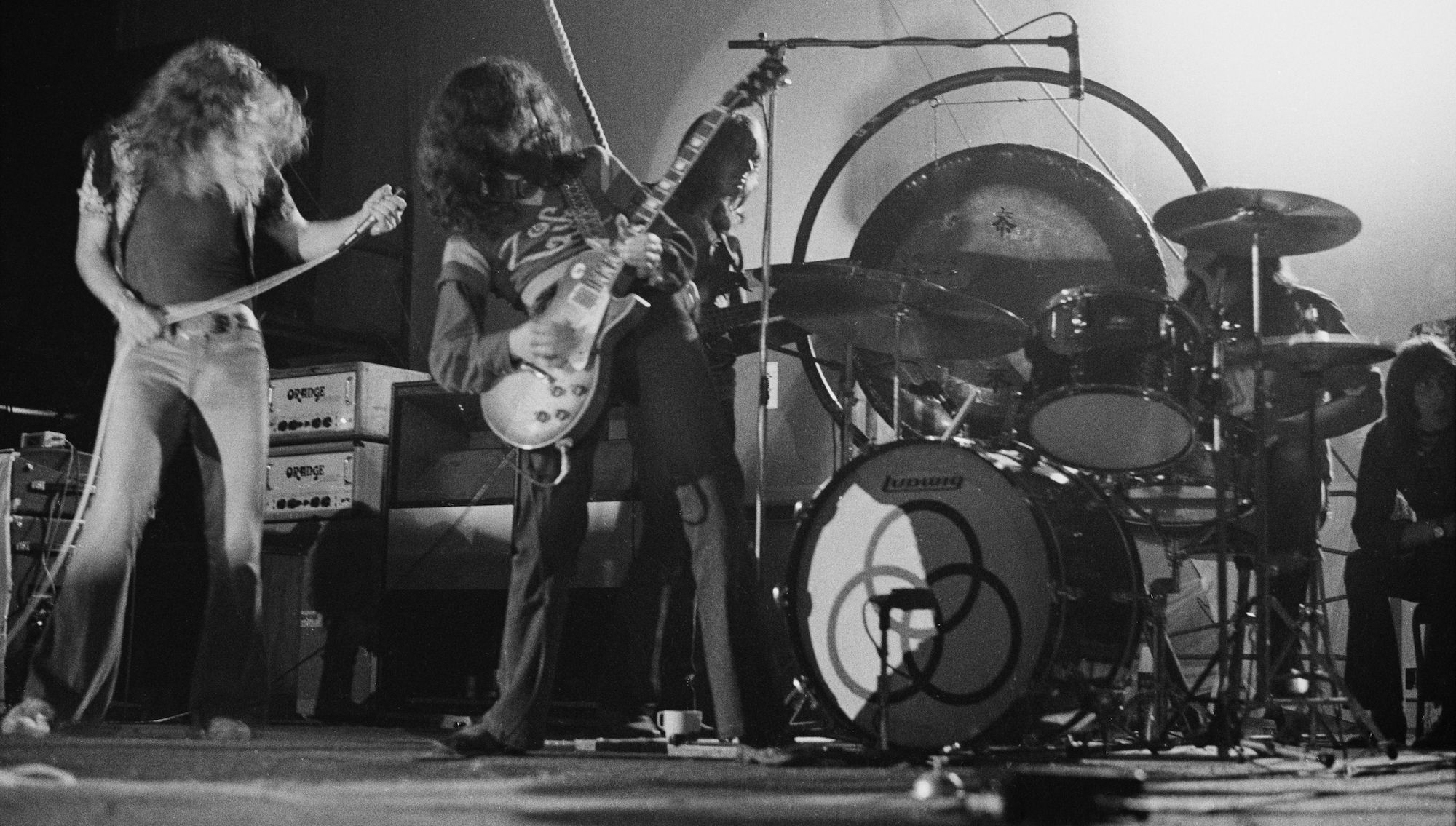

“I Was Seduced By the Beauty of What a Six-String Instrument Could Do": Jimmy Page Reflects on His Roots as a Guitarist and the Creative Drive That Made Led Zeppelin Rock's Defining Force

In this Guitar Player exclusive, Page shares his gear epiphanies and war stories from a 60-year career at rock's summit.

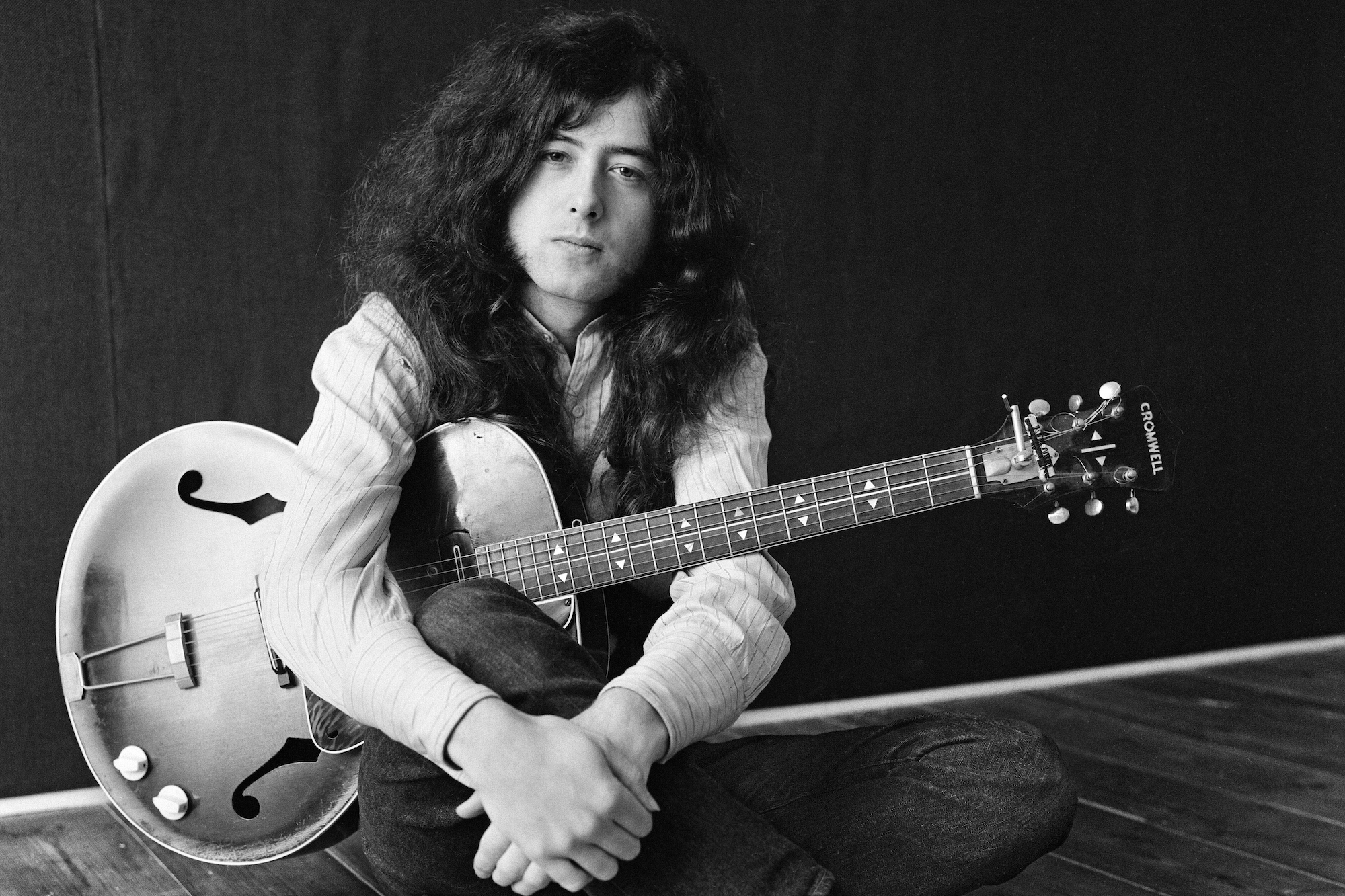

He belongs to an exclusive group of guitarists who rose to prominence in the 1960s and became the leading influencers of modern music for decades to come. But Jimmy Page looks back on his nearly 60-year career with a simple appreciation for the fact that it happened at all.

“I’m just blessed to have had a life where I was able to make my living out of my passion,” Page says today. “Not only that, but to have been able to have made some important musical statements along the way in various genres, and to have made people happy and inspired people in the way that I was inspired. And that passes on the baton to the next generation.”

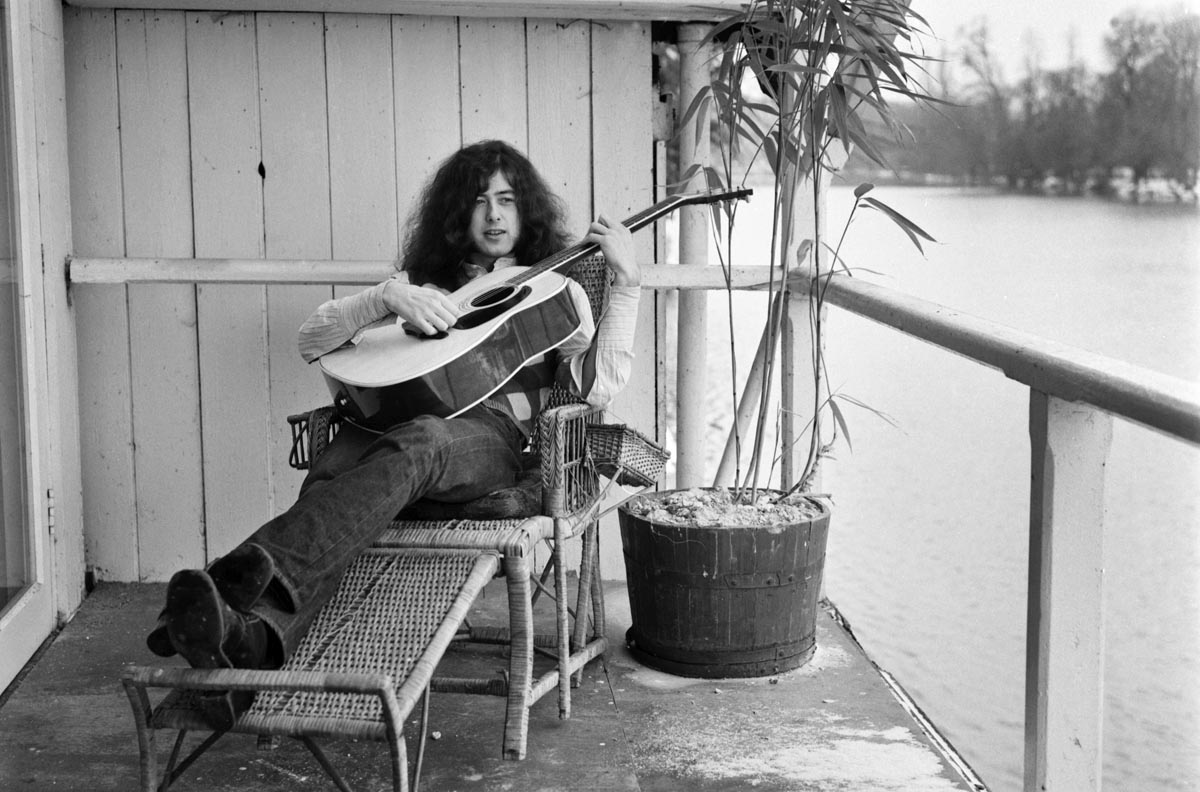

Reflection has been on Page’s mind quite a lot lately as he’s prepared a new book for publication. Titled Jimmy Page: The Anthology, the new tome from Genesis Publications finds the former Led Zeppelin guitarist delving into the iconic guitars, stage costumes, vinyl records, and other mementos from his long career.

The book is the follow-up to his Genesis book of 2010, a photographic autobiography that presented a visual history of his musical life.

I was seduced by the beauty of what a six-string instrument could do, whether it was acoustic or electric, and I was never happy to stay in one style for too long. I always wanted to challenge myself

Jimmy Page

In the same way, Jimmy Page: The Anthology is a personal journey through the objects and artifacts of one of rock music’s most important guitarists, narrated entirely in Page’s own words, and with contextual photography spanning six decades.

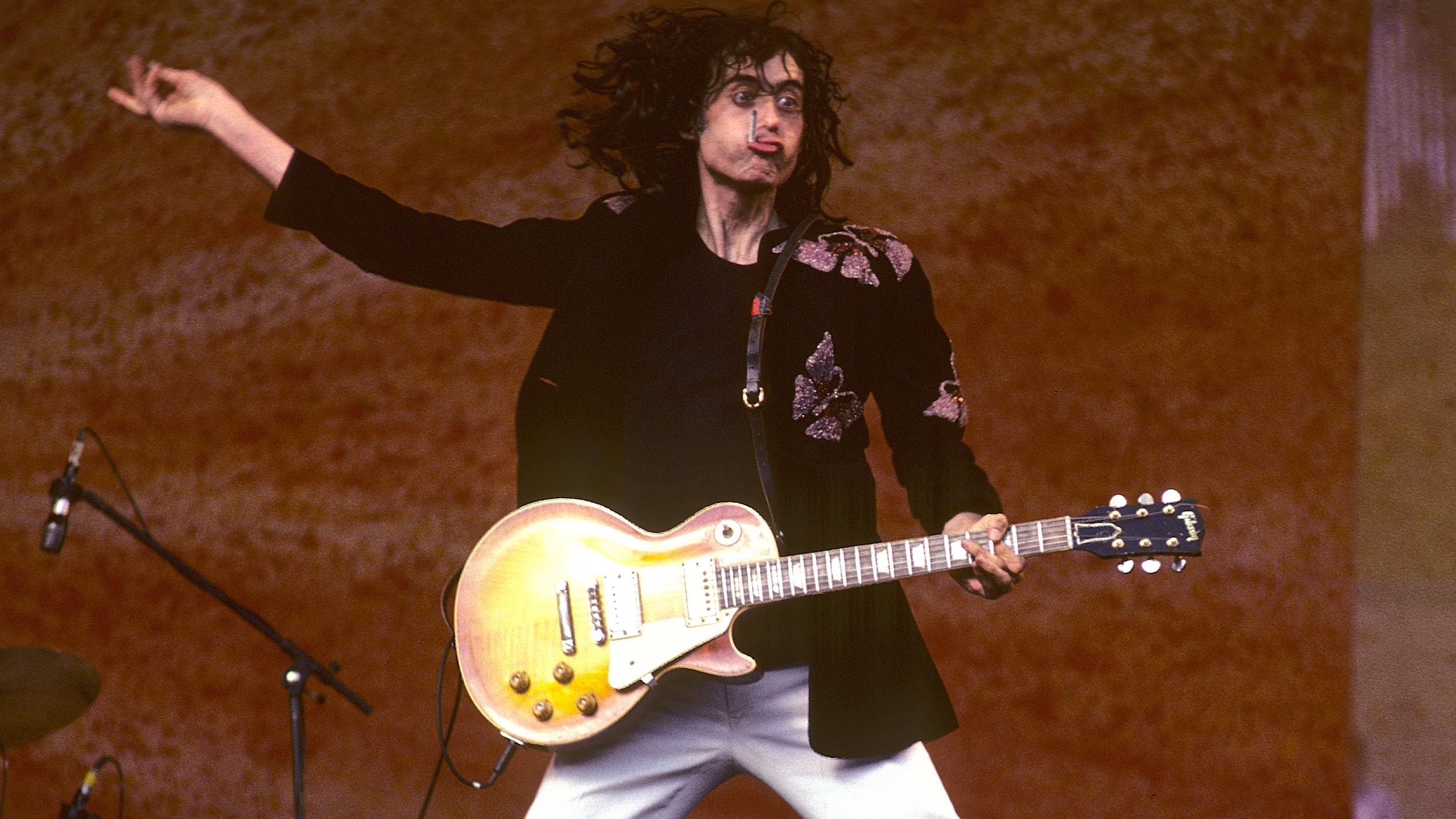

Beyond the photos of Page and his various groups, photos of his guitars – including his “Dragon” Fender Telecaster and “Number One” Gibson Les Paul Standard – are what stand out.

As Page notes, “I was seduced by the beauty of what a six-string instrument could do, whether it was acoustic or electric, and I was never happy to stay in one style for too long. I always wanted to challenge myself.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

As the book came toward its release date, we were fortunate to speak with Page about the book, his career, and the insights that led him to lay the foundation for what became heavy metal. He was generous with his time and memories.

As you’ll read in the following extensive interview conducted by contributing writer Ian Fortnam, Page touches on many aspects of his career, from his nascent interest in rock and roll to Led Zeppelin’s influential reign in the 1970s, with plenty of discussion along the way about guitars, production, and the concepts that led him to forge the sound of heavy metal.

The first image in Anthology is a photograph of you singing in the choir at St. Barnabas Church in Epsom, presumably your first experience of public performance. Were you a willing chorister, or did you need coercion from your parents?

"No, not at all from my parents, actually. I voluntarily went to the church and joined up with the choir. I was compelled to. One reason why I would do that is because, in those days, rock and roll appeared on the airwaves and then it was stamped on by the BBC, etc, so you would find ways to actually hear music.

"We were lucky in Epsom, because there was an external swimming baths, and it had an area where there were amusements – pinball machines and a jukebox. It was like a pilgrimage to the jukebox, but the big boys used to go there, and I was quite young at that point.

"The church had a youth club where there’d be a dance and they’d play records, but to be in the youth club, you had to be in the choir. And I enjoyed being a choirboy, actually. I really did."

Once I heard rock and roll, I was infected by it, really, and there wasn’t going to be a cure. I didn’t want to be cured

And you got to wear the surplice [the white linen vestment worn by choristers]. It must have been your first excuse to wear fancy clothes.

"Absolutely. You’re right. You can see a connection, can’t you, decking oneself out for the performance?" [laughs]

As a child, you experienced hi-fi sound for the first time courtesy of your neighbor’s stereo. It seems that from the very beginning you weren’t just entranced by music but by the process of capturing sound, because, in many ways, therein lies the magic.

"Yes. Thinking back to write the book, I thought about pivotal points. And when I lived in Feltham [Page’s home prior to Epsom], my parents and I were invited to someone’s house just down the road, and he had this stereo setup. What he played at the time were some sound-effects records, the classic one of course being of the train going across the speakers – that sort of thing.

"And for a young boy, this was pretty amazing stuff. I was probably about eight, and he played some classical music. So you really felt the depth of it, and there’s absolutely no doubt that had a serious effect on me.

"What is interesting in the equation is that there wasn’t anybody in my family who played guitar. I had an uncle who played pub piano. He could play various songs, but he never taught me anything.

"He wasn’t actually willing to teach, but when we moved from Feltham to Miles Road, in Epsom, there was a guitar left behind in our new house by the previous owners. And that was like a really weird intervention, where the guitar sort of found me."

That is such a great Excalibur story.

"It honestly is. It's like, whether I wanted to be a musician or not, I was going to be one. But yes, I was fascinated by the whole process of being enveloped by sound and being part of it. And also, being in a choir, there’s the whole ambience of it. It’s funny how I was picking it up as a kid. And once it came to the point of hearing rock and roll coming from America, it was just a youth explosion of music.

"I’m so fortunate to have been born at that time, to witness that moment. It was like a line: On one side of it, everything is very quaint and old-fashioned, and suddenly there’s this whole explosion of adrenaline, music, and attitude.

"And of course we got skiffle as well, so you’re listening to all this stuff, and it’s like it came from another planet. With skiffle, Lonnie Donegan made it look like it was possible to access the music. And I had a guitar sitting in the house untuned; nobody had ever played it.

"And then there was a connection I made with this friend Rod at school, who showed me a few chords. And that was it. Once I heard rock and roll, I was infected by it, really, and there wasn’t going to be a cure. I didn’t want to be cured."

I got headhunted by Red E. Lewis to go and play in London, which was pretty amazing for somebody who was still at school

When your Excalibar guitar outlived its usefulness, it was your parents that bought you your first proper guitar, your Hofner. They appear to have supported your musical endeavors from day one.

"They certainly did. I always had to do my schoolwork as well, but they could see that all of the rest of the time I was obsessed with the guitar. And when I started playing songs that they’d heard on the radio, they were like, 'Wait a minute – he's really getting into this seriously!'

"I don't know where it ever went, but that original guitar wasn't the easiest to play. The strings were miles away from the fingerboard – not too far away that they would inhibit one from wanting to play it, but my parents said, 'We’d like to get you a better guitar,' and the Hofner was the particular one they agreed to get.

I was really keen to play the blues. And when I say 'the blues,' definitely the Chess catalog

"My dad could understand that, suddenly, his son’s playing the guitar that was left behind in the house, and Christmas is coming, and my birthday wasn’t far away, so the Hofner came as a multiple present. [Page was born January 9, 1944.] And boy, oh boy, I was really thrilled to bits to have that.

"But then it got to the point where all the music I was listening to was being played on solid-bodied guitars, and so I said, 'I need to trade in my guitar.' And their attitude was, 'You can do that, but you’re going to have to pay for it.'

"In those days, up to the age of 21, your parents had to sign for you to pay on an installment plan, and so my dad said, 'I’ll be the guarantor, but you’ll have to pay for it.' And that was fine. Those were the rules, and I stuck to them."

So from your early teens, you were devoted to the guitar. Other than those first few chords, you were largely self-taught, with a certain amount of help from Bert Weedon’s Play in a Day guitar guide.

"Yes, you’ll find all the guitarists of that day had that book, because it did literally what it said. You could play in a day, or two, once you got the guitar in tune, and it was just a really useful thing."

Equipped with your solid-bodied Futurama, you graduated through the Paramounts to Red E. Lewis and the Redcaps at the age of just 15. Both groups seem very much based in rock and roll and rockabilly, somewhere between Johnny Burnette’s Trio and Gene Vincent.

"Yes, it’s definitely that sort of thing. I was listening to Presley, obviously, all the stuff that Scotty Moore was doing, and I was listening to Ricky Nelson for James Burton, and, quite right, Johnny Burnette and the Rock and Roll Trio. When I heard that, that seemed to be totally in another zone from any other rockabilly I’d ever heard.

"The guitar playing was so abstract compared to any guitar playing I’d heard. At that point, I hadn’t really come across the blues; all those early sets with the Paramounts were definitely rock and roll and not skiffle.

"I was playing with a band as an opening act on a Friday or Saturday night and I got headhunted by Red E. Lewis to go and play in London, which was pretty amazing for somebody who was still at school. And then I was asked to join Neil Christian and the Crusaders, and there’s quite a lot that goes on at that point, because by then I’d found the [Gibson Les Paul Custom] Black Beauty."

Simultaneous with your musical journey, you were graduating through epic mythology and poetry, from The Odyssey and Beowulf to On the Road and the Beats – literary influences arguably as essential as the blues to the band that Led Zeppelin became.

"Well, yes, I guess so. I see your point, but how it works is by the time Red E. Lewis becomes Neil Christian, I’ve got a pal who was collecting rock and roll records, and then he stopped buying all his White records and only bought Black. So it was gospel, R&B, and blues, and he was getting records from the States. So I fell into it really luckily.

"He was living literally just down the road from me, so I could go and listen to this amazing stuff. I soon realized that there’s a poetry within the blues as well. The path to that was that Presley had covered a number of blues artists on his early Sun records, and that was really great.

"But during the process of that, people were going, 'Who is Sleepy John Estes? Who is Arthur ‘Big Boy’ Crudup?' So my friend was getting all of these sort of things in, and that’s where I heard everything in advance of what was coming later.

"I couldn’t necessarily play it, but I started to get my head around it. So I had rockabilly and rock and roll, Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis, and then it started moving into the blues: Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Albert King..."

You went to the American Folk Blues Festival in Manchester in 1962, which seems to have been a pivotal moment. [The event featured Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, Memphis Slim, Willie Dixon, T-Bone Walker, and many others.] Blues seemed to usurp rock and roll in your affections and indirectly led you to art school in 1963.

"Well, in the Neil Christian and the Crusaders set lists, we were doing 'Train Kept A-Rolling,' 'Honey Hush' and that sort of thing, but we were also doing Chuck Berry’s 'No Money Down' and Elmore James’ 'Dust My Broom.' But when you were playing dance halls, which we were, they just wanted Top-20 material, and you can tell that from the Beatles’ first album [1963’s Please Please Me]. They were covering the Tamla stuff, 'A Taste of Honey,' and the like.

"But I was really keen to play the blues. And when I say 'the blues,' definitely the Chess catalog, and it was in advance of everything that was going to come. And down south, obviously, it was the Stones who really brought that into the spotlight, but we were in advance of that.

"At the Manchester festival, I met Mick and Keith. They didn’t have the Stones then; they were just blues enthusiasts on a pilgrimage, like all of us, and we were in a house where the guy had just got the Howlin’ Wolf album with the rocking chair on the cover [Wolf’s eponymous second album of 1962, a collection of 12 previously released Chess singles].

"Nobody had heard it up until then, but we all heard it that day. So yes, that was one life-changing thing, but everything is changing your perspective on things, broadening your outlook and opening it out."

Around this time you also had your first taste of production with Chris Farlowe and the Thunderbirds. How did that come about? You were able to finance the session, so clearly Neil Christian and the Crusaders were starting to bring home the bacon by then.

"Chris Farlowe and the Thunderbirds were one of the bands that used to come down from London and play at the Ebbisham Hall in Epsom every now and again, certainly once a month if not once a fortnight, and they were phenomenal.

"Their musical taste was fantastic, and I always thought they were an incredible band. They had an upright bass, drums, and this guy Bobby Taylor on guitar, and he was something special. I always had a thing for that band.

"I had a little bit of money, not much. We went into a demo studio, and they had about an hour. Instead of doing a couple of songs, we got the whole album done. Even though I was paying for it, technically it’s my first production.

"I know that Chris Farlowe got a record deal on the strength of that, because his first record was called Air Travel [a play off the name Thunderbirds], and I’m pretty sure that was a result of somebody going, 'My god, we’ve got to have this singer!' But they did the classic thing of sticking him in with studio musicians, pretty much the same way as they did with Neil Christian. We weren’t even there."

Soon enough, you became one of the most in-demand session players. Aside from your obvious technical chops, what setup constituted the signature Jimmy Page sound palette that kept producers coming back?

"The electric guitar that I’ve got at that point is the Gibson Black Beauty [Les Paul Custom], so the combination is the Black Beauty and the DeArmond foot pedal [the 610 Tone & Volume Pedal]. I’d worked out a whole style around that, so that was my signature.

"The bottom line is that, in the studio world, all the musicians were considerably older than I was. The youngest one would have been seven years older than I was when I first ventured in there, and their points of reference would only have been more or less back in the Bill Haley days – maybe a bit of Eddie Cochran with Jim Sullivan, but they weren’t cutting their teeth on all the blues stuff and the R&B and everything else.

"So, suddenly, I come in as this new kid on the block, and I’ve got all of these strings to my bow. I was playing fingerstyle guitar and slide, and I was playing harmonica. I look back at this period and I think, How the hell did I do that?

"How did I manage to go in there, faced with nothing but a chord chart? It wasn’t music to begin with, and if you made mistakes or you mucked about, you would never be seen again. So clearly I was able to deliver. And if they asked me, 'Can you come up with something on this?' I’d say, 'Sure!'"

With music changing so rapidly in the early to mid ’60s, I imagine you were unique in the session world for your ability to speak this new musical language. You had the blues in your vocabulary, while your contemporary veteran players were essentially products of Tin Pan Alley.

"Yes, I think you’ve hit the nail on the head. I could fit in right across the board in the session world, and I was really, really in there. There’s no doubt about it – I was officially in."

And your taste stretched into areas that were almost uniquely exotic for the early ’60s. You had a sitar very early on. You listened to Alan Lomax’s field recordings, flamenco, and Indian and Arabic music, elements of which you’d later incorporate into your recordings with the Yardbirds and Zeppelin.

"I’d listened to Indian music. I’d accessed that on the radio, and this was way in advance of the Beatles. My father worked in a factory near Heathrow where they made wire and cables. Not guitar cables – big industrial stuff.

"He was the personnel manager, and there were a lot of Asians working there, and I said, 'Dad, would you ask around and see if anyone there knows anything about sitars? See if anyone can access one from over there.' And there was a guy who said he’s going to get one sent over, and it arrived in this makeshift plywood box.

I come in as this new kid on the block, and I’ve got all of these strings to my bow. I was playing fingerstyle guitar and slide, and I was playing harmonica. I look back at this period and I think, How the hell did I do that?

"In those days you could freight things and people would take care. Now it would probably be smashed to pieces. It had loads of straw in the box, and I took out the sitar, and there was this beautiful thing. I had absolutely no idea how to play it. There are all these sympathetic strings on a sitar, so as I plucked one string, the whole thing started to resonate and I thought, Oh my God!

"Sonically, all my learning was from listening to things and making my own interpretations of what I heard, but this was something else! Of course, later I got to meet Ravi Shankar at a concert in London. My friend and I were the only two young people there, and he gave me the tuning for the sitar.

"Now, this is how the weird synchronicity happens: The maker of this particular sitar was Rikhi Ram, and it wasn’t an expensive, top-of-the-range sitar. But when I went to the musical instrument exhibit at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art [Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock & Roll, which was on exhibit from April to October 2019], they had a beautifully crafted sitar of Ravi’s, and there was the same name of maker: Rikhi Ram!

"Can you imagine what an experience it was to actually see that? Because I had no idea who makes sitars. So, oh my God, what a moment that was. I’ve had a bit of a charmed life, no doubt about that."

Of course, as far as the 1960s went, your work with the Yardbirds and Led Zeppelin is just the tip of the iceberg. Presumably you could have subsisted very comfortably on session and production work alone whether you’d joined a band or not?

"Yeah, but when I’m in the Yardbirds, I’m still having to do sessions at that time. For example, I did the Joe Cocker With A Little Help From My Friends album [recorded early 1968, and released in 1969].

"But once it gets to the point of Led Zeppelin and I know what I want to do as far as production goes, I don’t do any more sessions, and I don’t want to do any more productions for anybody else. What I want to do is have everything that I can possibly bring to the party totally in-house."

I’d always been interested in listening to the ambience of the room and how people would record. I would listen to Les Paul and get a real master class in how things are done

Obviously, you played on a succession of historic sessions with everyone from Tom Jones through the Who, the Rolling Stones, and Cliff Richard to David Bowie. What was the most valuable lesson you learned during this period?

"Whenever I listened to recordings, whether they be classical or electronic, Little Richard or Howlin’ Wolf or Johnny Burnette, I’d always been interested in listening to the ambience of the room and how people would record. So I would listen to Les Paul and get a real master class in how things are done there.

"I’d done home recordings, but after a while, once I got into the studio, I could talk to the engineers in between sessions and ask, 'How’s this done? How’s that done?' After a year or two, it eventually got to the point where I could play them records and ask, 'How is that literally done?' I’d have my own idea of how it was done, but I would learn how it was done technically.

"So, bit by bit, I was learning that aspect of it during what I would call my self-taught apprenticeship of being a studio musician. I learned the whole studio discipline of how quickly and efficiently you could do things and still be able to keep making things up on the spot, instantly. But then I also learned how to record and produce sessions, and how not to record and produce things. So it really was a great apprenticeship."

With all that studio experience you picked up along the way, might the Yardbirds have lasted longer with you in the production chair rather than Mickie Most [the British pop producer behind many successful English acts, including the Animals, Herman’s Hermits and Donovan]?

"Well, look, Mickie Most was really, really good in his field. He knew how to do singles. We could list so many artists that he was really marvelous for, but when there was this break within the Yardbirds, he was given a package of Jeff Beck and the Yardbirds [Beck and the Yardbirds split in 1966, leaving Page as the group’s sole guitarist]. So he had two artists that he needed material for.

"He clearly saw Jeff on an instrumental path, which was right, but for the Yardbirds, the singles started to grate. Up to this point, the Yardbirds had had such a wonderful catalog.

"When Jeff and I were in the band, we did 'Happenings Ten Years Time Ago,' which was pretty cool. But when we did an album, it was really telling, because Mickie wasn’t interested in albums; he was only interested in doing singles.

"So, bit by bit, we started to record tracks which we should never have done. The Yardbirds had done all of this magical stuff, and then to do things like 'Ten Little Indians,' it was just absolutely wrong.

"I’m just really annoyed that they’re even out there. It was said that they wouldn’t be released, and they were. I don’t think that helped the spirit of the band. I did help put things together on the Little Games album, because Mickie wasn’t there a lot of the time, but I wasn’t officially in a production role."

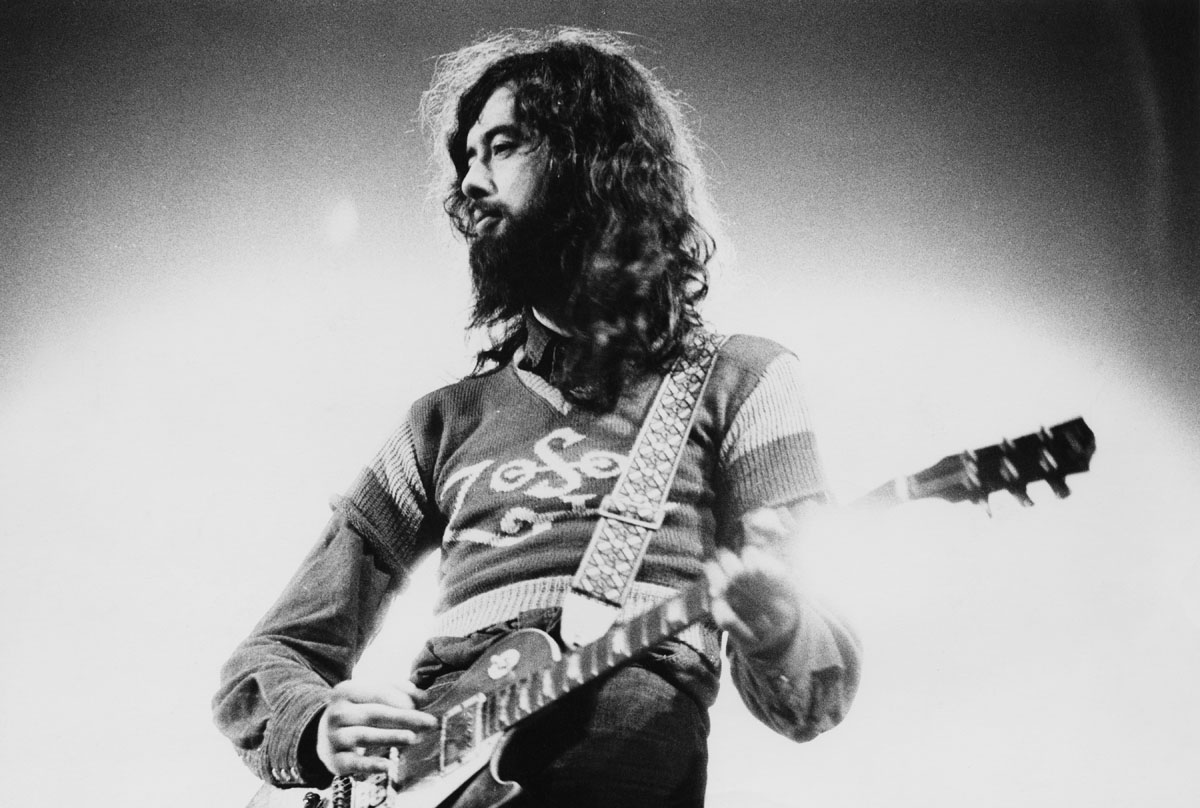

The more I listen to Led Zeppelin, the more I reach the conclusion that the heaviness of those recordings isn’t about volume but the richness of the guitar tones and the method of recording the drums, especially on the recordings made at Headley Grange. [Parts of Led Zeppelin III, Led Zeppelin IV, Houses of the Holy, and Physical Graffiti were composed and/or recorded at Headley, a former English workhouse.]

As the band’s producer, what influenced you when you were mapping out the Zeppelin sound? Or was it a simple flash of inspiration when faced with the potential of those four musicians?

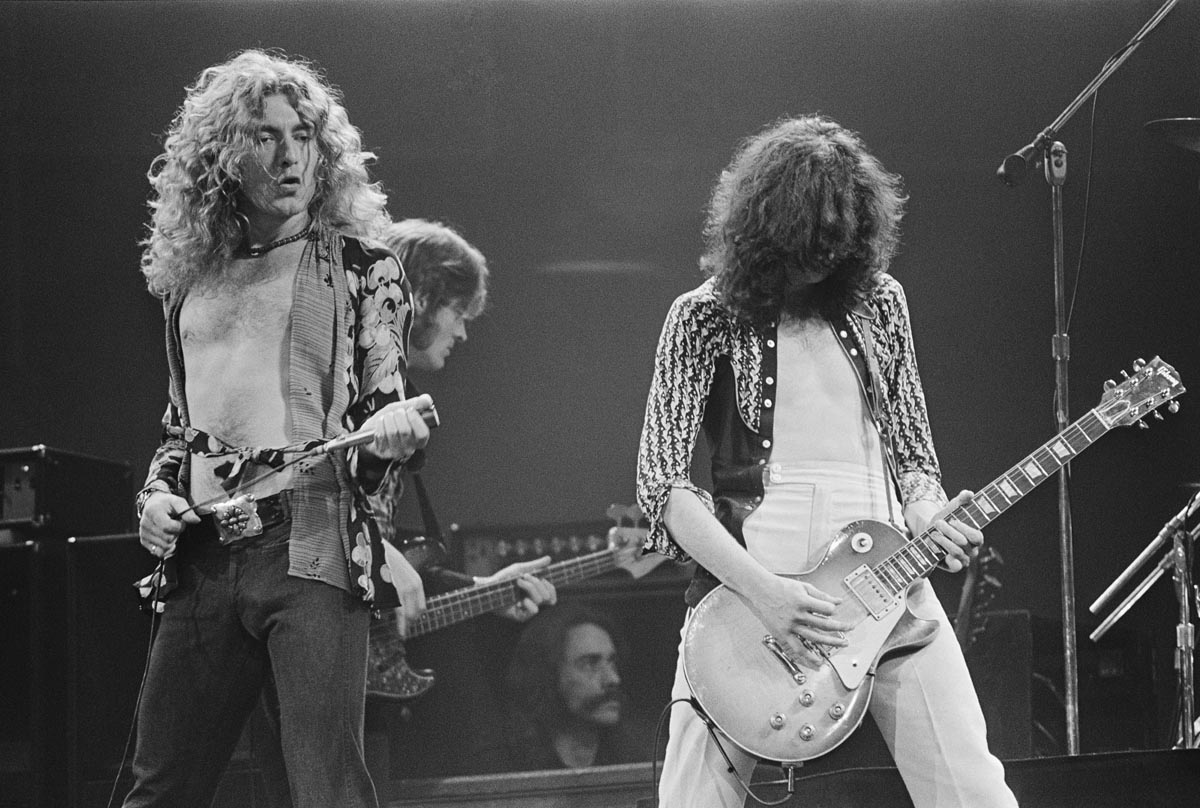

"I would say the first album has got so many ideas in it, and you can hear that those ideas develop through the second album, the third album and all the rest of it. So it becomes a point where I’ve tried with 'Babe, I’m Gonna Leave You,' with the power of John Bonham, to build the drama of the song.

"I was using the same aspect with things like 'Ramble On,' with 'What Is and What Should Never Be,' and that sort of thing, where you have these choruses which are not really super loud, but it’s really the intensity that gives it the drive.

"So you can start playing with the dynamics of everything. I got this right from the early days of the first album. It seemed to be ahead of the game of what others were doing, and that’s always good, because you’re turning people on, musicians as well as the listening public."

When people talk about the birth of heavy metal, they always focus on people turning the amps up. That heaviness is purely a product of volume, but listening to early Zeppelin, you can hear that the hugeness of the drums is enhanced by the ambience of the room.

"Well, John increased the size of his drum kit, so by the time you get to, say, Headley Grange and another drum kit arrives, the drums were larger sizes. But even with the smaller kit for the first album, he had volume to his drums. It didn’t sound like a little jazz kit.

"He knew how to play with his own dynamics. To get more level out of the drums, he would do that with his tuning. As we were playing, he’d hit a heavy bass drum – just one beat – and you’d feel it go through your body.

"He was such a technician. He was absolutely unbelievable. He was somebody who could do a roll on bass drum with one foot. I mean, it’s just unheard of! People say they can do it, but you see how long they can do it for."

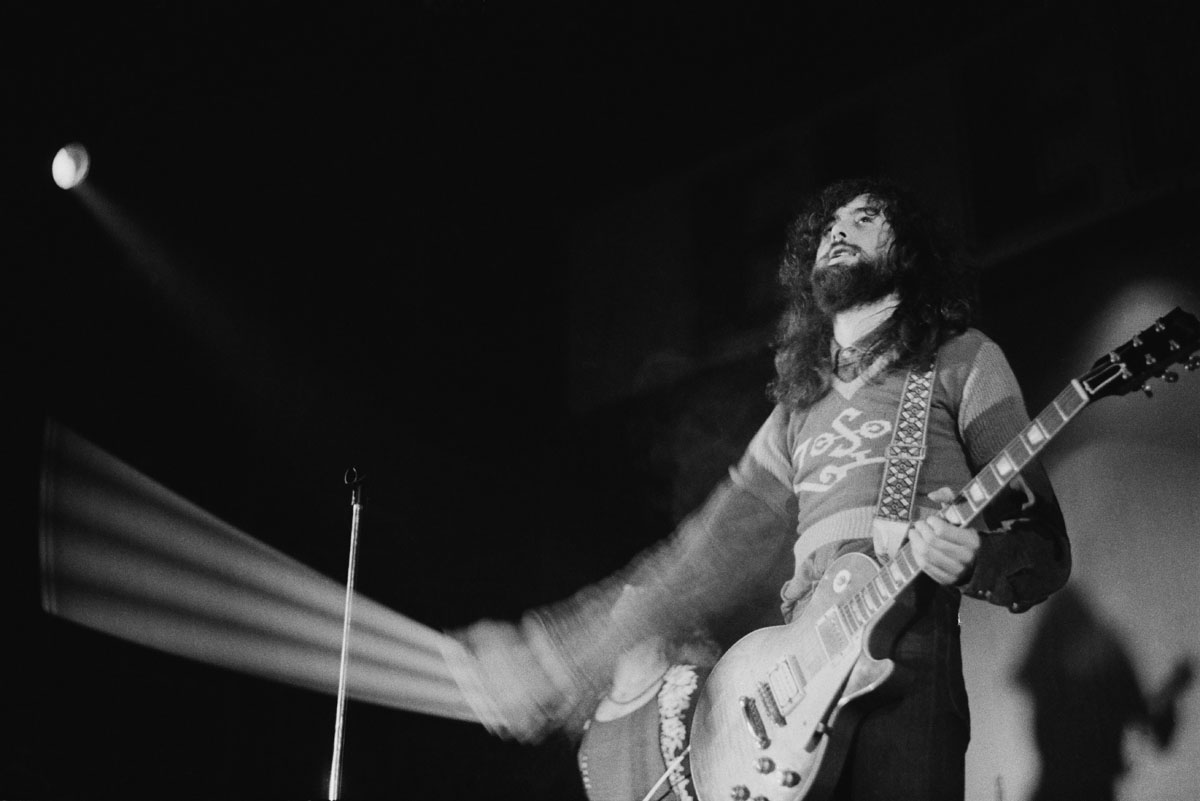

You’ve never made life easy for yourself, using the violin bow in tandem with the Echoplex and Sonic Wave Theremin. There are a lot of variables in there, but like the intrinsically improvisational nature of Zeppelin, you’re constantly challenging yourself. Was the magic of playing with Zeppelin in the fluid nature of what would happen from performance to performance?

"I was always trying to improvise, even in the days of Red E. Lewis and the Red Caps. I’d try to play faithful reproductions of the solos on those records that we’d cover, and then I’d put in my own little interpretations. Being a session musician? It was improvising all the way through, and then it comes to the Yardbirds – same deal.

"But then it comes to the point in Zeppelin where you’ve got a tour de force like 'Dazed and Confused,' and it’s 25 or 27 minutes long in concert, but it’s only two verses. There’s literally only two verses to it!

"So yes, it was challenging, but it was fun. Plus, you had the musicians who were really up for it as well. John Bonham was super up for all this stuff, and it was great for Robert because he could call out for a number at any point that he wanted to. And John Paul Jones was great.

"We had a great rhythm section there, and it was a great power trio for Robert. And yeah, we could go through all these great phases of different styles and attitudes to music. But yes, the improvisation – that 'Dazed and Confused' thing – we’d go out onstage every night not knowing what was going to happen between going on and coming off at the end. Every night was different, and it was brilliant."

How did you come to use the Parsons-White B-Bender, which makes a big appearance on In Through the Out Door?

"I heard the Byrds’ [1970] Untitled album – it’s a live album – and I thought, What the hell is he doing? And it turned out it was Clarence White playing on the Gene Parsons and Clarence White invention, which was his idea to make the string pitch up.

"You can hear Clarence use it on the Byrds’ Sweetheart of the Rodeo, but the live album is where I first heard it and thought, I can’t fathom this out – I don’t know how it’s done. Albert Lee was the first person I saw using the string bender, when he was playing with Eric Clapton.

"I was chatting with him, and he said, 'I’ve got one of these.' He let me have a go on it. I managed to get one, and then I started playing it in the days of Led Zeppelin. There’s a lot of it on the ’77 tour. It’s featured all over the Stockholm material, the stuff that occurs on Coda and the In Through the Out Door album."

You get different effects and you make up things around those, but I do prefer the raw edge of actually playing straight through an amplifier

When John Bonham died, Zeppelin were about to embark upon rehearsals for an American tour, your first in three years. Obviously, the tour never took place, but what were your feelings leading up to those fateful rehearsals at Bray Studios? Would Led Zeppelin have continued to make further albums, or were you already itching for fresh challenges?

"John Bonham and I discussed what sort of shape the next album should be, because each album was different to the last. It just so happened that Presence was basically a guitar album, so as John Paul Jones had his Dream Machine [the Yamaha GX-1 synthesizer, used extensively on In Through the Out Door], it was only right to do a keyboard album. So we had been discussing what we’d do for the next one, and there were definite ideas of what we could do."

You worked more than most with guitar synthesizers, especially on the soundtrack to Death Wish II [Page composed the soundtrack to this 1982 Charles Bronson action film]. You’ve always embraced innovation, but am I right in thinking that you’d rather simply investigate the possibilities of a guitar, a valve amp and some old-school effects pedals?

"Yeah, that’s true. I do like the sound of a guitar coming through an amp. I don’t like all that sort of rack equipment – the digital stuff. I’d much prefer to plug a guitar into an amp. Say you’ve got three amplifiers you’ve never played through before. You plug into one: 'Oh, that’s good.” You plug into another and say, 'Oh, dear, no! Gosh, what’s the third one?'

"And suddenly the third one just sings. It’s pushing the sound back at you, and there’s an interaction between the pickups of the guitar, and there’s this sort of loop that just inspires you to be playing. You know what I mean?

"So, yes, I do prefer that. There are so many ways to do it, of course. You get different effects and you make up things around those, but I do prefer the raw edge of actually playing straight through an amplifier. Yeah, I do."

In 1981, you, Chris Squire and Alan White teamed up as XYZ. The recording sessions seemed to bear significant fruit, yet the music remains unreleased. In Anthology, you teasingly hint that it might come out one day. Have you any plans to return to the recordings any time soon?

"It was the very first thing that I did after a break of not playing the guitar after losing John. I got the guitar from storage and started playing it again, and it was an instant connection. I had a studio, and because I’d been very friendly with Chris Squire, he said, 'We’ve got some stuff. Let’s come together and see what we can do.'

"And he had this novel name: Because there were two former members of Yes, he thought it should be XYZ, as in ex-Yes and Zeppelin. Which was a bit of fun. And they were such great musicians that it really did me a world of good. I had to be on exactly the same level as they were, so the level of concentration and commitment to it was really great.

"But what I don’t know is what bits and pieces they brought to the party that may have ended up on Yes records. One that we did there as an instrumental eventually came out as 'Fortune Hunter' with the Firm.

"But those guys were just in a league of their own. So it’s really good music. I haven’t actually returned to it yet. I will, because I know how darn good it is, and then I suppose one would just have to speak to those that were involved, and families and stuff, and see whether it could come out one day. I hope it does.

"There is a cassette version of it that is terrible quality, and it’s out there on the internet. Nevertheless, it’s fascinating to listen to."

Led Zeppelin reunited in 2007 for the Ahmet Ertegun Tribute at the O2. In Anthology you reveal that you would like to have done two nights, but might you have actually preferred to do 10?

"Initially there were going to be two nights, with us on one night, along with other Atlantic artists. The idea was that we would do a half-hour set, but I said, 'I’m not rehearsing to do a half-hour set! We’ve got Live Aid to correct, and the Atlantic 40th.'

[Led Zeppelin’s reunion performance at Live Aid on July 13 1985, was marred by a lack of rehearsals, Page’s out-of-tune guitar and Plant’s hoarse vocals. Their Atlantic 40th Anniversary performance on May 14, 1988, suffered from a disagreement between Page and Plant as they walked to the stage about performing “Stairway to Heaven,” and Jones’ keyboards were missing from the live television feed.]

"I thought, We’re gonna go out there and stand proud, you know? So that means we’ve got to do a proper set, and that’s what we did. So, yeah, a second night would have been really, really good. In fact, the following day, I started to get really jittery at 7 o’clock, and I thought, I know what it is. It’s because I’d paced myself toward doing the O2, and now there isn’t an O2 to do!"

With Led Zeppelin being such an instinctively improvisational beast, I’d imagine that when it’s roused into full wakefulness, it’s not easy to put it back to sleep without running its full course.

"I think that’s true. We’d had a lot of fun up to that point in the rehearsals, because mainly it was the three of us. There’d be Jason [Bonham], John Paul Jones and myself, playing together so that Jason felt really part of the band, as opposed to like he’s there because he’s John’s son. He was there because he was a damn good drummer, and it was right that he should be sitting in that seat. But he needed to know that.

"And yeah, a lot of rehearsals went into it. We were ready for it. It had been said that there was going to be a tour. There weren’t any dates put in, but obviously we had honed ourselves to the point where we were ready. But then there has not been any discussion about any tour ever since, nor will there be. So there you go. It’s just one of those weird, odd things in the world of Led Zeppelin – really, another part of the Led Zeppelin phenomenon."

I’ve always got ideas, and the day that I wake up and haven’t got any ideas of what to do and how to do it, that for me will be a very sad day

What’s next? Are you working on any projects at present?

"One of the things I was complaining about before we all had to lock down was that I wasn’t having enough time to play guitar. I was able to actually say, 'Well, this is it. You can do it every day now.' So it’s given me an opportunity to reconnect properly with the guitar."

Anything solid you can tell us about, the sort of ideas you’re playing with?

"No, not really, but obviously I’m never not doing something, and I’m never not doing something that’s going to surprise people. It’s like when I did a spoken word project with my girlfriend [2019’s Catalyst, with poet Scarlett Sabet]. Nobody was expecting me to do that, because nobody had done that before.

"It was really wonderful to do. But I’ve always got ideas, and the day that I wake up and haven’t got any ideas of what to do and how to do it, that for me will be a very sad day. And that day looks like it’s some way off yet."

Deep down, are you still that enthusiastic young lad who’s curious to unlock every new possibility that lies within your guitar?

"No. But I’m his great-grandfather."

- Jimmy Page: The Anthology is out now via Genesis Publications.