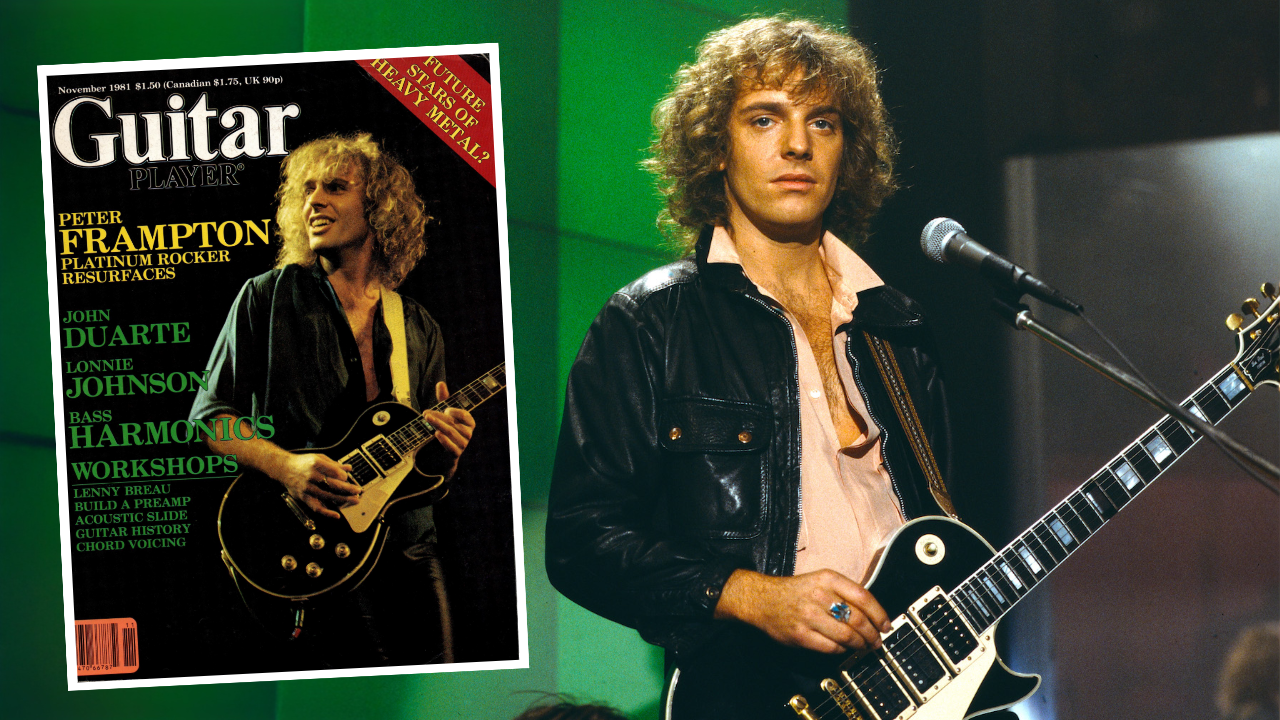

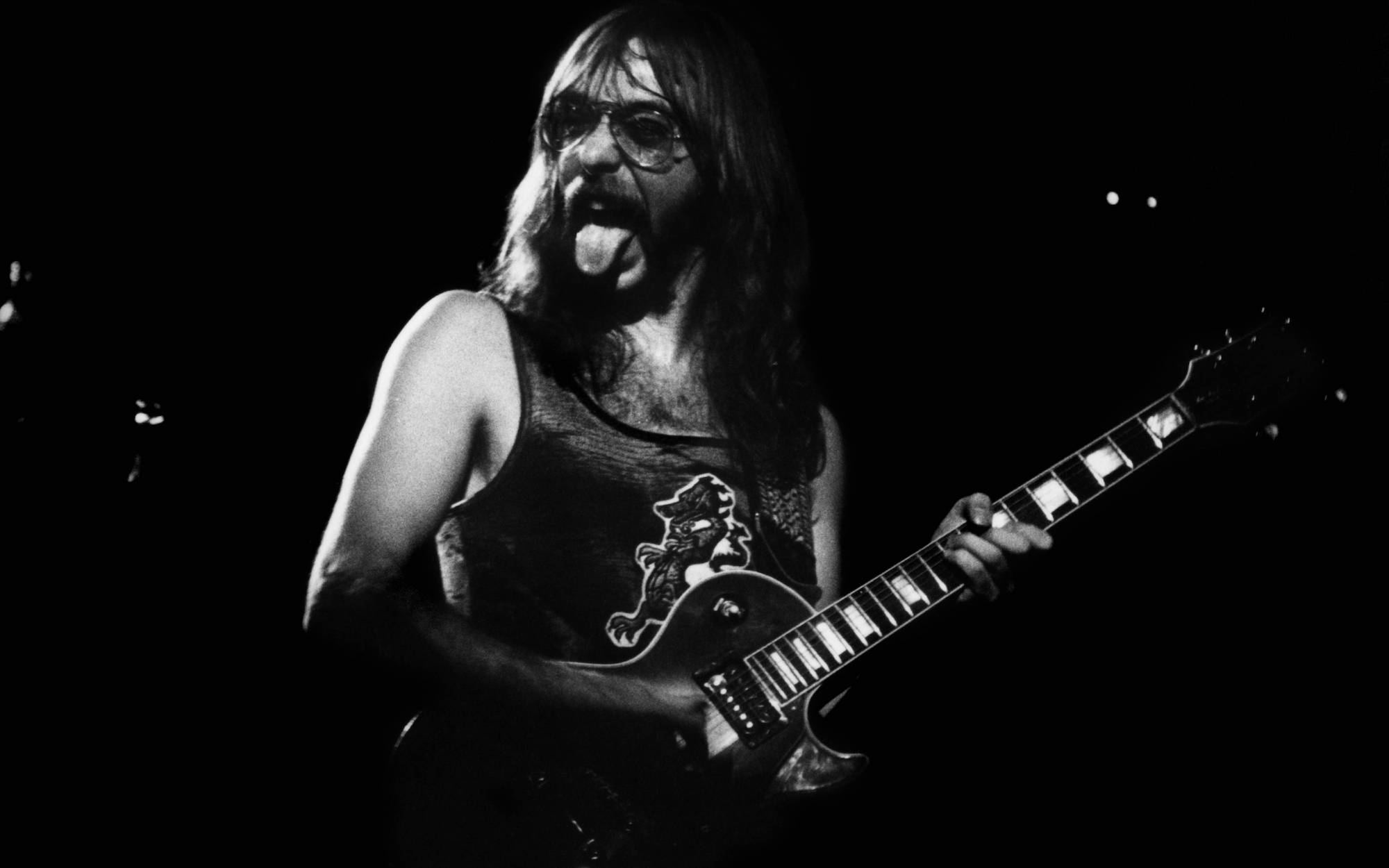

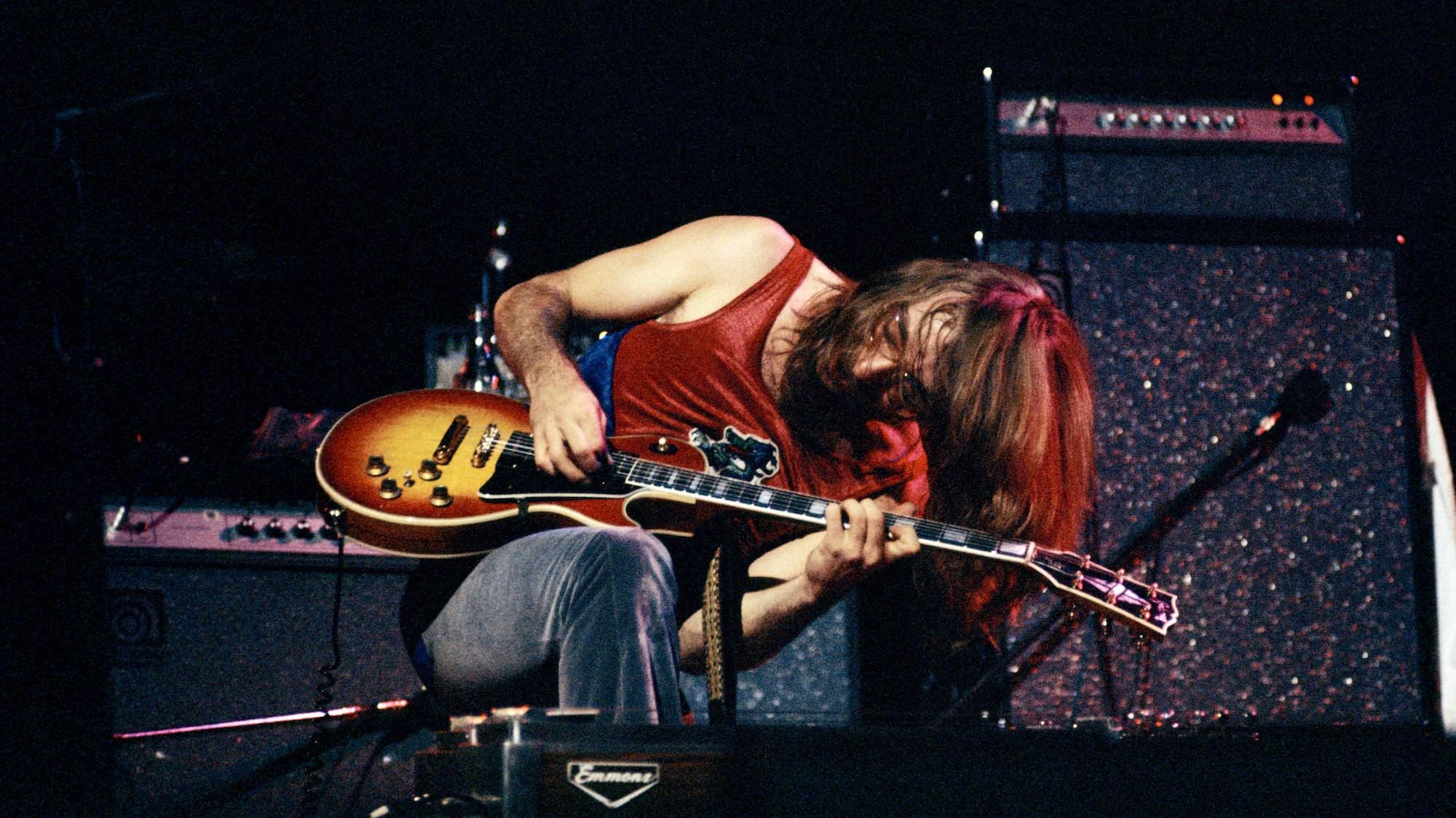

Jeff “Skunk” Baxter: "Whether it’s a Guitar or a Missile-Defense System, There’s Always a Way to Make it Work Better"

Throughout Jeff “Skunk” Baxter’s storied career, various theories – some fairly tame, others pretty outrageous – have been floated as to the etymology of his famous nickname.

In the annals of juicy rock and roll secrets, this one is a biggie. When asked if he would choose the occasion of this Guitar Player interview to make some news, the guitarist lets out a good-natured laugh. “Not a chance,” he says. “A girl’s gotta have some secrets, right?

"There seems to be a lot of interest in this little tidbit,” he adds after some reflection. “And all I can say is, the answer will be revealed one day in my book. Not before.”

Whenever that book arrives, it will no doubt feature an extensive index to list even a portion of the albums and songs Baxter has played on since he began his professional career in 1969.

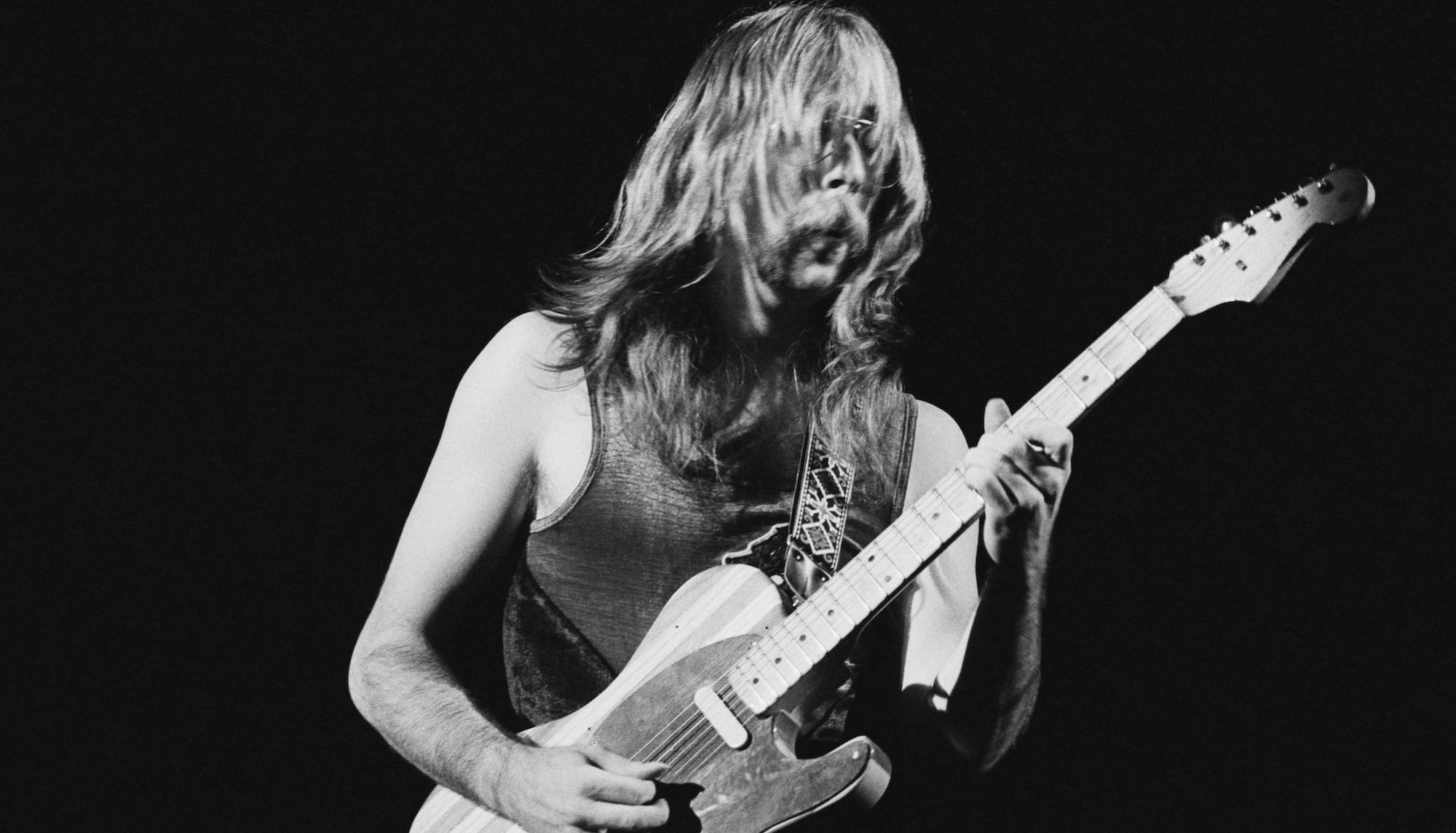

His spunky, melodic, and highly sophisticated approach to soloing – rocky enough for rockers, jazzy enough for jazzers – quickly made him one of the most in-demand, first-call studio guitarists during the glory days of the 1970s West Coast singer-songwriter period.

Over the years, he’s performed on hundreds of records for a glittering array of music’s elite, including Barbra Streisand, Dolly Parton, Donna Summer, Joe Cocker, Rod Stewart, Carly Simon, Hoyt Axton, Bryan Adams, Ringo Starr, Glen Campbell, Joni Mitchell, and Rick Nelson, to name a few. Making Baxter’s accomplishments even more remarkable is his membership in not one but two legendary bands.

As a cofounder of Steely Dan, he appeared on the group’s iconic first three albums – Can’t Buy a Thrill, Countdown to Ecstasy, and Pretzel Logic – and performed sumptuous solos on numerous tracks, most notably “Rikki Don’t Lose That Number,” “Bodhisattva,” and “My Old School.”

He followed up that stint with a five-year run in the Doobie Brothers, which saw the group transform from rowdy rockers into multi-Platinum, blue-eyed soul monsters. Baxter contributed standout moments that include his searing solo in the Motown cover “Take Me in Your Arms (Rock Me a Little While),” a star turn in which he constructs a perfectly formed mini composition that builds to a thrilling climax.

“Quite honestly, I never imagined that I would have had this kind of success,” Baxter says. “All I ever wanted was to play the guitar in a band and have fun. I didn’t know that it would lead to being a studio musician and everything else that has come my way. Whatever expectations I had at a young age were certainly met, and as my playing matured, and I matured, so too did the opportunities.”

He pauses, then adds, “I think it’s important to recognize your accomplishments, but it’s more important to move forward. I’m privileged to be able to have the respect of my peers, but the success I’ve had came about because I applied myself. If I didn’t try my hardest, none of this would have happened.”

Self-taught as both a guitarist and guitar repairman (and later, as a designer and consultant for the Roland Corporation), Baxter established yet another career for himself in the early ’90s as a U.S. national security expert, once again under his own tutelage.

After reading various aviation publications, he wrote a paper suggesting that the U.S. military’s ship-based Aegis anti-aircraft system could be reconfigured as a missile-defense solution.

He gave the paper to former California Republican congressman Dana Rohrabacher, and in short order he became a defense consultant. Over the years, Baxter has worked for the Department of Defense, chaired congressional advisory boards, and done work for private defense innovators, such as Northrop Grumman.

Asked if he can draw any parallels between guitar playing and working as a military consultant, Baxter says, “Sure. Whether it’s a guitar or a missile-defense system, there’s always a way to make it work better. I always say, ‘A radar is just an electric guitar on steroids.’ If you understand the physics, then you can grasp the plethora of concepts that have to do with frequency, transducing, broadcasting, electronics…all that stuff. Being a guitar player, I’m a techno geek anyway, so this kind of thing comes naturally to me.”

Between playing in superstar bands (he was inducted with the Doobie Brothers into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2020), fielding recording session offers and working as a military defense analyst, Baxter squeezed in time to produce albums for Carl Wilson and Nils Lofgren, as well as for acts like Nazareth, the Ventures, the Stray Cats, and Billy and the Beaters.

It seems as if the one thing he never got around to was cutting his own solo album. He certainly thought about it, but it always seemed like something he would do down the road. “My standard line was always, ‘I’ll get to it someday,’” he says.

That day is finally at hand, with the release of Speed of Heat (BMG/Renew Records), a dazzling mix of covers and originals that Baxter co-wrote with his keyboardist and producing partner, CJ Vanston.

“I met CJ years ago at a jingle session in Chicago,” he explains. “It was one of those moments when I had this incredible, nonverbal communication with another musician. We just clicked, and I said to him, ‘If I ever do a solo album, I’m doing it with you.’”

Originally, Baxter envisioned a record of instrumentals, and indeed, there are sublime examples, such as a loving rendition of “Apache” (made famous by the Shadows and guitarist Jørgen Ingmann) that brims with stinging and singing guitar lines, as well as a soaring and sensual version of “The Rose” (known to music fans from Bette Midler’s multi-Platinum-selling original for the film of the same name) that takes flight with Baxter’s lyrical pedal-steel playing.

Other instrumental highlights include the turbo-charged rocking title track, an exquisite ballad titled “Juliet” that features an aching nylon-string acoustic interlude, and a spacey, almost cosmic R&B remake of Steely Dan’s “Do It Again,” on which he layers offbeat, jazz-tinged leads.

Over time, the album grew to include vocal tunes, and one of the most startling cuts on Speed of Heat is yet another trip through Baxter’s Steely Dan past: a raucous rock reinvention of “My Old School” that sees the guitarist turn in a rare and robust singing performance.

His onetime Doobie Brothers bandmate Michael McDonald is in top form on the gripping ballad “My Place in the Sun,” and country superstar Clint Black shows off his pop sensibilities on the hook-filled winner “Bad Move,” which features a blazing guitar-and organ throwdown between Baxter and Vanston. And on the blues-soaked “I Can Do Without,” Baxter and guitar star Jonny Lang (here singing in a sinuous falsetto) engage in epic call-and-response leads.

“The record was such a joy to make,” Baxter says. “CJ and I have such an affinity for composing and playing together, and we were blessed to have such amazing and talented artists join in.

"The great thing was, they would come to me and say, ‘Hey, I heard you’re doing a solo album. Can I be on it?’ Which was great, but the thing we put to everybody was, ‘If you’re going to be on the record, you’re going to write with CJ and myself, and we want you to do something you’ve never done before. We wanted to go on a new journey with everybody. And I think we got there.”

You started playing the guitar at age nine. I understand that Howard Roberts was one of your first influences.

"Absolutely. Even at a young age, I was struck by his sense of melody. Each solo he played was its own composition. The same is true for Wes Montgomery. Whether he was doing it on the fly or not, it had a structure to it. And, of course, I loved the Ventures because they played the melody of a great song. That hit me as a young kid, and it stuck with me."

What kind of guitar were you playing as a kid?

"I started out with a $16 Mexican guitar that my dad bought for me, and then I borrowed a number of guitars from different friends. Because of my father’s job in advertising, I grew up in Mexico City, where electric guitars were extremely expensive. But I was lucky enough to have friends who had guitars, so there was stuff around to play.

"The first guitar that I ever bought was a Fender Jazzmaster, based on the advice I got from [the Ventures’] Bob Bogle after I’d written him a fan letter."

As a young teenager, you played in bands in Mexico City. How developed were your abilities on the instrument at the time?

"Well, I’m still not fully formed, and I sure wasn’t then. But I had a lot of energy. I knew four or five chords, and I was a fairly aggressive player, which was adequate for what we were doing. Everybody was just starting out, really. Even the best rock and roll bands, the most famous ones, were basically three- and four-chord bands."

Were your parents cool with you playing in bands as a young kid?

"My mom wasn’t thrilled. My dad wasn’t too sure about it, but he was always very supportive."

Just a few years later, you wound up working at music stores in Manhattan. How did that happen?

"My father sent me to prep school in Connecticut to further my education. Because Connecticut is a long way from Mexico City, there were occasions where, instead of flying back home for Christmas or Easter vacations, I would just stay with friends in New York. That’s when I started to work at some of the music stores on 48th Street, which was the mecca for buying musical instruments.

"I was about 13 or 14 at the time. I started repairing guitars, which I’d already been doing in Mexico because there was no one else to do it. I was working at Jimmy’s Music Shop, but there wasn’t a ton of repair work coming out of there.

"One day, Dan Armstrong approached me and said, 'I’ll pay you $5 an hour to come and work with me' – which was a lot more than I’d been making. I went to work for Danny, and that’s when I really got to hone my skills, especially in terms of electronics, and I got to meet every great guitar player, because they all came to Dan Armstrong’s shop."

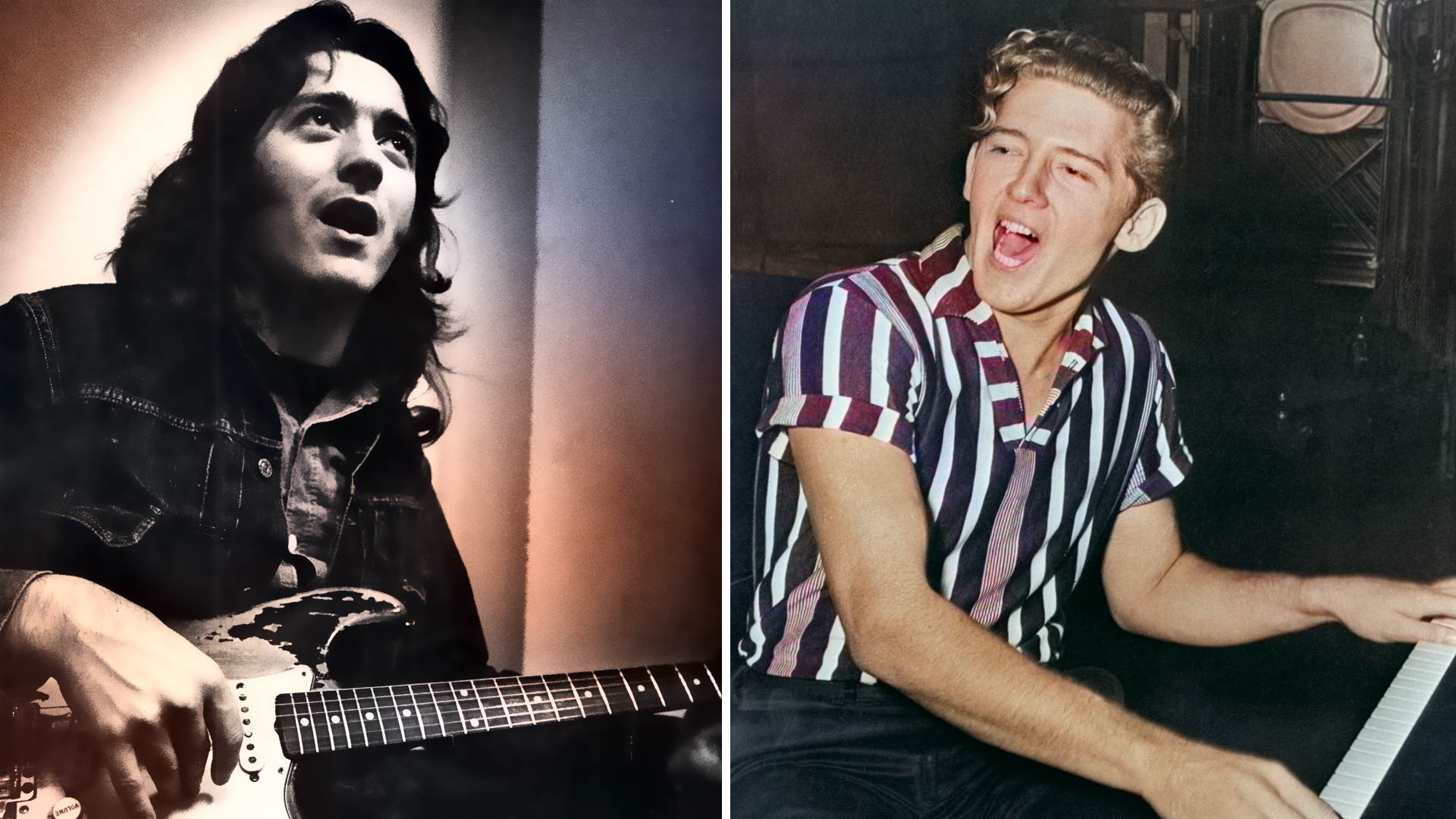

Tell me how you came to meet Jimmy James, whom we all know as Jimi Hendrix. You actually played a gig with him, right?

"This was at Jimmy’s Music Shop. A gentleman came in with a beat-up Fender Duo-Sonic. He wanted to upgrade the instrument or get a nicer guitar. I had already customized a Fender Stratocaster for a left-handed player who wanted to play righty; I made some changes to the vibrato arm and a few other small things. But the guy never showed up, so I just traded Jimmy James the Strat for the Duo-Sonic.

"I got in trouble with Frank, one of my bosses. He said, 'What the hell was that?' I said, 'Well, he seemed like a nice guy.' And for that, I was docked two weeks’ pay. One day after that, Jimmy James came back to the store and invited me to come down to a club to see him play.

"One night his bass player was late, so I got a chance to play a couple of tunes with him. We became friends – not deep, deep friends, but friends enough. We had some interesting conversations from then on. He was very kind and complimented my playing. Of course I loved his playing. I was just such a fan of Curtis Mayfield and Little Beaver [Willie Hale], and I could see how they influenced him. We had that in common."

It’s such a rear-view mirror question, but did you have any sense that Jimi was destined for greatness just a few years later?

"No. But when Chas Chandler came into the club to listen to him play, I did see the kind of audience Jimi had and response he got. You knew there was something there. Randy California was in the band, and he was a friend as well. We both agreed that this guy was going somewhere, but we couldn’t tell where. All you had to do was look at people’s faces as they listened to the music. There was certainly the suggestion that this wasn’t a mere club band."

A few years later, you moved to California. Was it your idea to pursue the session scene?

"I came out to audition as a pedal-steel player for the Flying Burrito Brothers. At the same time I found a job at Valley Sound, which was a place that repaired guitars and amplifiers. They hired me right away because they were looking for a guitar repair guy. I started repairing guitars for a number of the players in Los Angeles, and that’s how I got introduced to the studio scene.

"Being in L.A. at the time was like a rocket boost. I met all the great players. I didn’t end up playing with the Flying Burrito Brothers, but I did play steel for Linda Ronstadt and did occasional gigs in the house band at the Palomino Club. Pretty soon we put Steely Dan together."

When Steely Dan formed, was your guitar role clearly defined from the start?

"Not so much, but I do think they wanted me to bring my experience and skills and particular approach to the game. I had met Walter Becker and Donald Fagen on the East Coast through [ABC/Dunhill Records staff producer] Gary Katz, who was producing this band called Bead Game. I was doing sessions in New York and Boston at the time. Gary said, 'Would you be willing to work on a project that I’m doing with two songwriters, Walter Becker and Donald Fagen, and a singer named Linda Hoover?' I said, 'Yeah, sure. It’s a session – I’ll do it.'

"After the first session, Becker and Fagen said, 'Wow, we’ve never heard anybody play guitar like that on our music.' And I said, 'Well, I’ve never heard music like this. I really like it.' We all agreed that we wanted to find an opportunity to put a band together.

"Becker and Fagen moved out to Los Angeles to become staff songwriters at ABC/Dunhill Records. Me and a few other guys – David Palmer, who was a singer I knew from New York, and Jimmy Hodder, who was the drummer for Bead Game, and their friend Denny Dias on guitar – put together a band based on the songwriting opportunities that Becker and Fagen had at ABC/Dunhill.

"We were rehearsing in Jay Lasker’s office – he was the president of the record company – and one day Jay came in and went, 'What the hell is this?' Gary Katz said, 'Well, we have this band...' Jay said, 'Okay, let me hear it.' We played for him, and he signed us."

Did the band start out fairly democratic?

"In the beginning, it was somewhat democratic, because I think Becker and Fagen relied a fair amount on the expertise and capabilities of the other musicians in the band. As we began to progress, and obviously as the band became more successful, Becker and Fagen wanted to take more and more creative control.

"I had the attitude of a studio guy, so I never really felt insulted or anything. After a while, though, they didn’t want to tour, and I really enjoyed playing live. By that time I was already playing with the Doobie Brothers, as well."

You played some brilliant solos on Steely Dan tunes, particularly “Rikki Don’t Lose That Number” and “My Old School.” Becker and Fagen had a reputation for putting musicians through their paces. Did they direct you, or could you play what you wanted?

"Most of the time, I could play what I wanted. As far as those two solos were concerned, it was pretty much that way because there was no real idea in their heads of what they wanted.

"The 'My Old School' thing was basically, 'Take your best shot.' Much of that was a first take. We had a thing in the band called 'gotta have it,' which meant that, even though Walter and Donald were certainly in the driver’s seat, if you did something that you really wanted, then you would say, 'Gotta have it.' The solo in 'My Old School' was a 'gotta have it.'"

What kinds of guitars were you playing during this period?

"I had a Telecaster I had rescued from a dumpster out at Fender – the body anyway. The solution I used to strip the paint from the guitar was so industrial strength that it actually delaminated it, so I had to use some gaffer’s tape to put the guitar together.

"I installed a pair of Skunk-o-Sonic pickups that I had designed. That was one instrument that I used. The other was a Stratocaster I had built myself out of curly maple. Actually, the guitar I used on 'My Old School,' a Stratocaster, I routed it out in the parking lot at Valley Sound the day before the session. I just assembled it, wired it up, plugged it in, and there it was."

What is the secret to Skunk-o-Sonic pickups?

"Well, let’s see… I wind them on my mom’s sewing machine, which is the only thing that ever had a variable speed and a spindle that I could wind on. And I use a special gauge of wire that works for me. The magnets are pretty standard, but it’s important to use the heavy-gauge guitar strings.

"You have to understand, a pickup is basically a current generator. The more you can stimulate the magnetic field, the more tonality and harmonic resonance you can get out of it. That’s really the secret of good tone. It’s not just the fundamental; it’s everything that’s clinging to it harmonically."

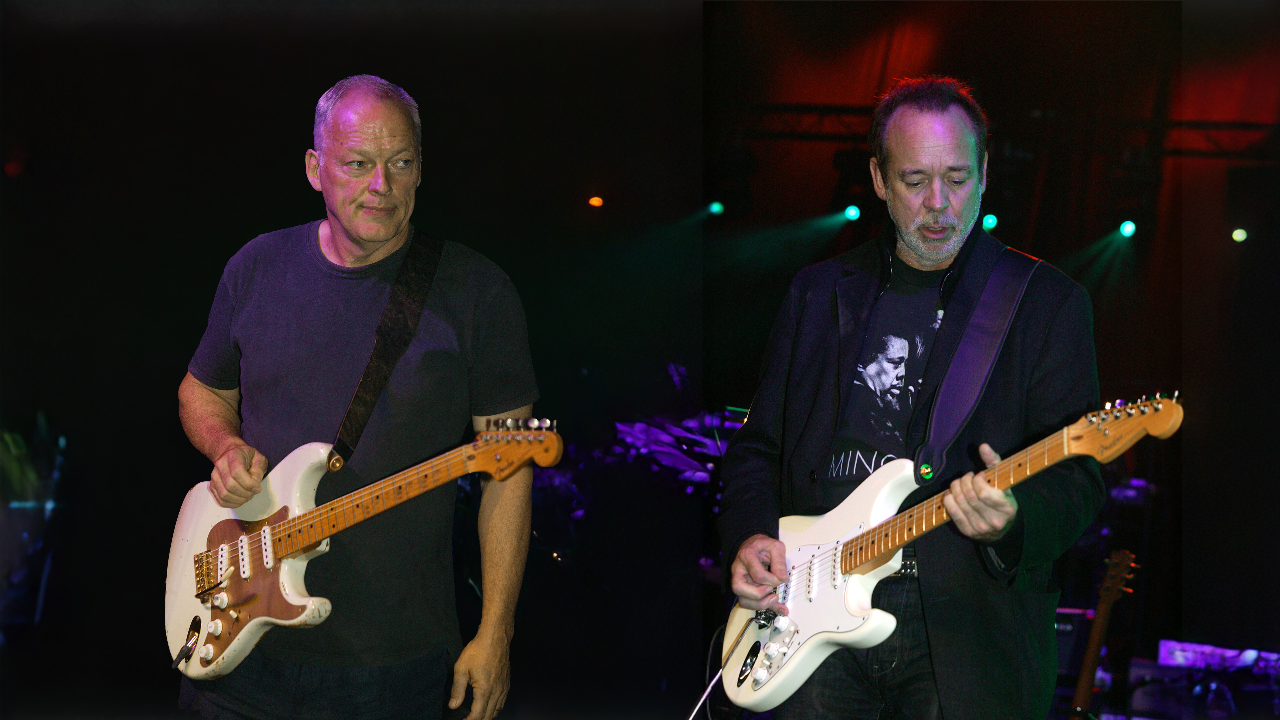

When you joined the Doobie Brothers, you were paired with their guitarist, Patrick Simmons. Did you develop a good relationship as players?

"Oh, yeah, it was excellent. I think we had very complementary styles, and my style of guitar playing – having had a lot of experience in the studio and being sort of eclectic – complemented both his playing and his sense of composition. Patrick and I worked well together. We became friends and loved playing together."

The musical direction of the band changed radically once Michael McDonald joined in 1975. You guys went from being kind of a rough-and-ready biker-rock outfit to doing more R&B/pop. You were the one who actually brought Michael in, right?

"That’s true. I had been in the band for about a year, maybe more. Tom Johnston, who was one of the lead singers, was having some severe health problems at the point. We did a gig at Louisiana State University, I think, and he couldn’t come out onstage. I went out and said to the audience, 'We can either give you your money back, or if you come back in 10 days, we’ll put on a great show for you.' Nobody turned in their tickets.

"Then I called Michael McDonald – I knew him from playing with us in Steely Dan – and I said, 'I’m sending you a one-way ticket. You want to join the Doobie Brothers?' And Michael, to his credit, said, 'Sure,' and flew out. We rehearsed eight hours a day for about eight days. Then we went out to play and got five encores. I thought, I made the right decision.

"Now, where do we go from here? Michael contributed keyboard playing, but he began to compose as well – and did a hell of a job. There was no real telling where the band was going. One thing I did want to create was the opportunity for the band to develop as players.

"Tiran Porter is probably one of the most underrated bass players on the planet. That guy is ferocious. I mean, talk about melodic. And Pat Simmons is a great guitar player – nobody does it better. Keith Knudsen is a great drummer and a tremendous human being. For my part, I wanted people to get in a particular head space, to move into an area where the approach to music was a little tighter, a little bit more in the Steely Dan genre.

"I remember when we were doing the [1977] Livin' on the Fault Line album – which I think is the best album the Doobies ever did – and Keith came up to me and said, 'I dropped a snare drum beat in bar 51.' And I thought, Bingo! We’re here. Everybody’s got the mindset. Not the Steely Dan mindset, but the mindset of looking at your playing from a little more of a disciplined perspective. I started booking the Doobie Brothers as a rhythm section for Hoyt Axton and Leo Sayer. I said, 'Let’s start doing sessions.'"

You left the band right after [1978’s] Minute by Minute became a ginormous smash. A lot of guitar players would have said, “Are you crazy?” Did you have any reservations about leaving when you guys had reached this incredible pinnacle?

"You’ve got to know when it’s time to go. With success comes different perspectives from different members of the band. I kind of could see where this was going, and I felt that it was the right time. I talked to a couple of friends whose advice I trusted. I talked to my dad, and he said, 'Now’s the time. Go when you’re at the top.' It was the right decision, because with that kind of wind at my back, it opened up tremendous opportunities.

"I really wanted to start producing records, and those doors opened very quickly. I was already a session player. Steve Lukather and I both joked that we were the only first-call session guitar players who were in famous bands."

So your decision to leave wasn’t because you were unhappy with the musical direction. Your attitude was more like, “My work here is done.”

"Well, yes. I consider myself a change agent. That’s certainly what my day job considers me – someone who approaches things from a non-traditional point of view. If you’re a change agent, part of your personality is understanding that there is a time after the change that you go on to do something else."

Between sessions and production work, you carved out a career for yourself as a national security consultant. I assume in the pantheon of guitar players, you’re unique in this regard.

"Actually, no – there’s Paul Reed Smith. Paul came to me some years ago and said, 'I have an idea for an underwater acoustic detection system. Let me show it to you.' I took a look at it and said, 'This is a cool idea.' I called Rear Admiral Nevin Carr over at the Office of Naval Research and asked him to check it out. He met with Paul, and now Paul has a company called Digital Harmonic that does a tremendous amount of work with the U.S. government.

"When I wrote my first paper on adapting a particular naval-fleet defense system that was designed to protect, to defend against air-breathing threats – aircraft and cruise missiles – I was very familiar with the radar in that system. Having read a couple of articles from some publications, I wrote a paper on how to convert that system to do missile defense. And that’s kind of how it all got started."

A lot of people in government are musicians. I saw a video of you recently playing in a band with Secretary of State Antony Blinken.

"Sure. He’s a pretty good guitar player and an energetic and ballsy singer. We have a band called the Coalition of the Willing. One of the guitar players is a former ambassador from Hungary. The other guitar player is the former Deputy Undersecretary for Department of Energy. The drummer was a former ambassador for Japan. The bass player was the former Undersecretary of State for Military Affairs. It’s that kind of deal."

When you guys get together, do you mainly talk military matters or music?

"Both. I do still do a lot of work for the Department of Energy. I did some work for the State Department, and certainly there was all kinds of tangential stuff. Mostly what we do is charity work, raising money for vets and certain charities. After you sweat out a version of 'Hoochie Coochie Man,' you sit down with different folks and you always have those discussions, especially during rehearsal."

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.