Jason Isbell on the Redemptive Power of Vintage Gear, Sweet Tones and Finding What Works for the Song

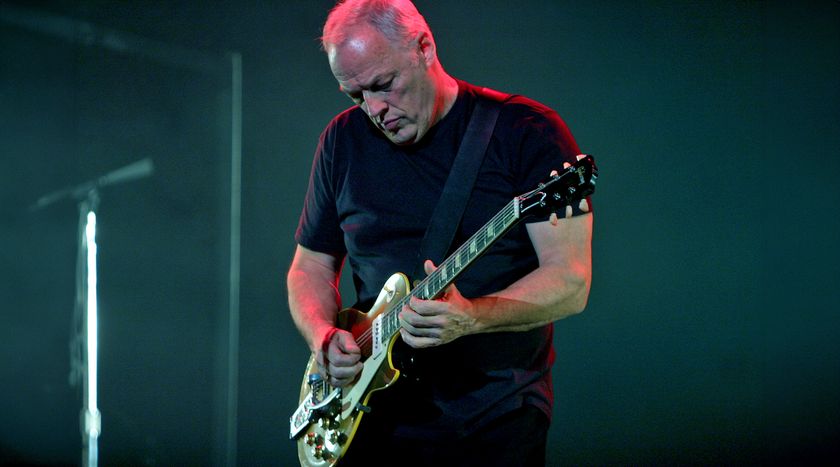

On 'Reunions,' Jason Isbell shows that his fretboard skills deserve as much recognition as his peerless songwriting.

Jason Isbell is seated at a small table inside the Barn, his cavernous rehearsal compound far outside of the Nashville sprawl, where the freeways and touristy honky-tonks yield to pastures of electric green.

Outside, a drizzling rain hangs in the early spring air. “If I’m in a big room like this, I’m thinking, 'Man, I could write about anything in the whole world.' The world is so huge.” He gestures, revealing seven hash marks tattooed onto his forearm, one for each year of sobriety. It’s easy to see how someone could get distracted here, even this far from Nashville’s rowdy Broadway strip.

Duesenbergs, Stratocasters and Telecasters of varying vintage hang from the charcoal-hued walls. Amp heads galore, including Sommatones and Magnatones, are stacked on road cases, and a 1972 Marshall gifted by Dave Cobb, who produced Isbell’s last four albums, rests on a matching ’72 cab that once belonged to Neil Young.

It’s one hell of a guitarist’s playground, and it’s the place where Isbell cranked out the riffs on Reunions (Southeastern/Thirty Tigers), his new album with his muscular backing band, the 400 Unit.

Whenever I don’t have anything else that I have to do, I play the guitar. I just love doing that so much now - even more than when I was a kid, because I’ve got all the cool shit that I wished I had then

Isbell has always been a guitar player first, but his once-in-a-generation songwriting talent has often overshadowed his fretboard work. After beginning his career with the Drive-By Truckers in the early aughts, penning rootsy classics like “Outfit” and anchoring the third guitar in the band’s caterwauling attack, he started over with the 400 Unit in 2007.

It was a slow build to his breakthrough, 2013’s Southeastern, which put his experiences falling in love and getting sober in sharp relief. On Reunions, he’s finally laying down the guitar chops that are usually reserved for his live audiences. This moment is a long time coming.

Over the past year and a half, Isbell has played sideman to Tommy Emmanuel, Sheryl Crow and the Highwomen, the country supergroup featuring his wife, Amanda Shires, who moonlights in the 400 Unit on fiddle when she’s not fronting her own band.

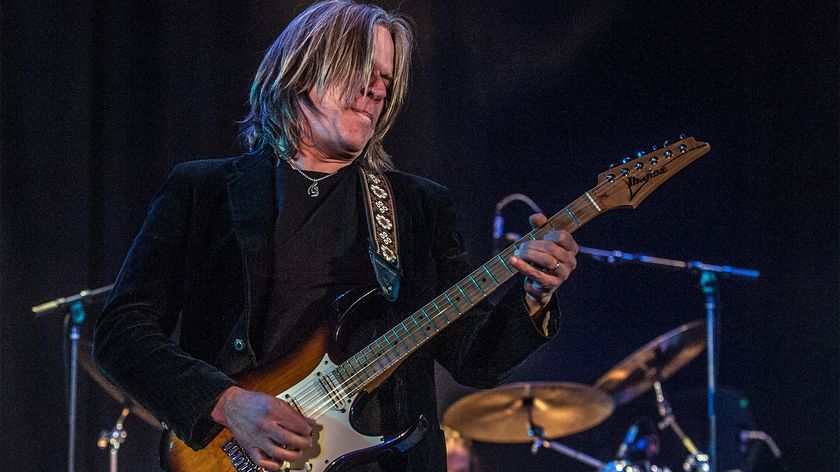

He even quietly played guitar on the theme song for the Monday Night Football opener that aired throughout the 2019–2020 NFL season. In his own shows, Isbell and co-guitarist Sadler Vaden have taken to nightly duels, usually on his blistering Truckers-era jam, “Never Gonna Change,” or a cover of the Peter Green/Fleetwood Mac song “Oh Well.”

For a while following Gregg Allman’s passing, they closed every show with a take on “Whipping Post” worthy of its southern-rock lineage. Reunions is vintage Isbell, a collection of tightly spun, plainspoken story songs from the four-time Grammy winner, but with a few important new twists.

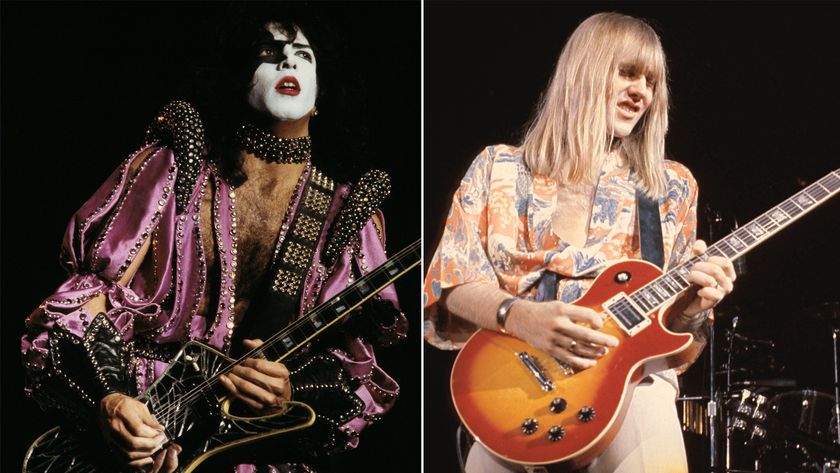

Influences ranging from Strat-wielding heroes Eric Clapton and Mark Knopfler to the Cure’s Porl Thompson weave around his trademark slide licks and riffs. And the 400 Unit, Isbell’s secret weapon, shows up ready to lay waste.

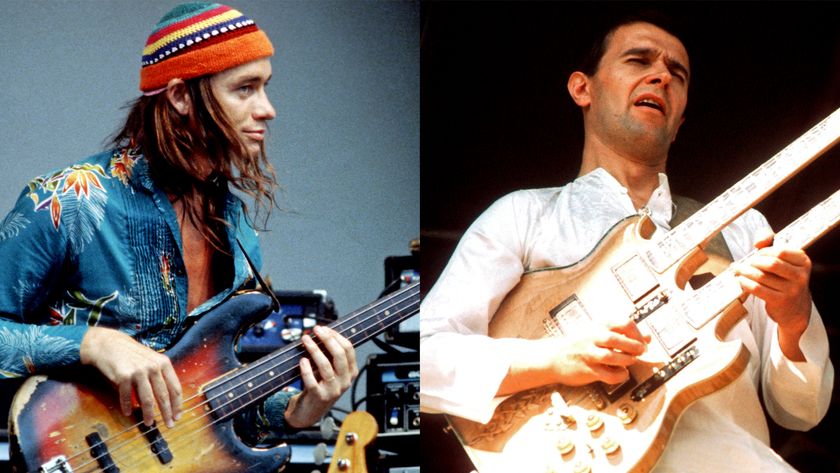

Bassist Jimbo Hart anchors the melodic underpinnings of the polyrhythmic “What’ve I Done to Help,” and plays Mike Mills to Isbell’s Peter Buck on songs like the roaring “Be Afraid.” From his home base outside of Music City, Isbell gives us a tour of the tones and inspirations behind Reunions.

You’ve been a guitar player all your life, but you’re more widely known as a songwriter.

Yeah, they didn’t give me the Grammy for playing guitar. [laughs] I’m glad that I can write songs, because the guitar player in me could not afford the guitars that the songwriter has purchased on his behalf. But originally, it was just like all my interests aligned. I read a lot when I was a kid, and I loved good songs. At some point it just made perfect sense to me to try to write lyrics.

Reunions features a lot of those guitars. “Overseas” might be the most guitar you’ve played on a song since “Decoration Day” with Drive-By Truckers.

There are a lot of guitar solos on this album, but it’s a tightrope, because you don’t want things to be gratuitous unless you’re working within that framework. If you’re making gratuitous guitar music, by all means, go for it. But listen to AC/DC. That’s some of the best guitar ever recorded, and none of it is extraneous.

Those riffs and solos are so memorable.

They’re singable and melodic and they’re just perfect, for the most part. Even though what we do is not a whole lot like AC/DC, I think that approach is the right one for song-driven music.

You want to serve the song, and once you’ve gone past that line, you’re making a different type of music, or you’re doing a poor job making the type of music you set out to do. I consider myself a guitar player first and foremost. That’s the thing I started doing first and the thing I still enjoy the most. But I’m here to tell stories, so the song is what’s most important.

That being said, we were able to find ways to make the guitar an important part of the record, and I think that happened because I started out writing that way. I didn’t use a capo anywhere on this album. That was harder than getting sober, making a whole record without a capo. [laughs]

But I wanted to do that, because if I’m playing something live one night and one of the guitars feels particularly good, I’d like to keep it for a few more songs, and I don’t like to tune onstage. If I’m using different capos or different tunings, then I’ll have a different guitar every time, and I wanted it to be like, If this Strat feels really good, I’ll just keep it for three or four songs.

Did you set out with a particular direction in mind for the album?

As the process goes on, you can’t help but see certain themes and certain sonic collections within the songs themselves. It became a really melodic album that I pictured from the start as having a higher fidelity and sounding like a lot of my favorite pop records.

There was something about the way location affected those records. It’s hard to put a finger on it, but I was in Alabama in the ’90s listening to Rolling Stones records from England in the ’70s, or from the south of France, and I went somewhere completely different.

That was really my ultimate goal on this record. I wanted people to listen to it and think, I’m not in my room right now; I’m not in my car right now; I’m in a different place in a different time in somebody else’s life.

You’re known for playing Les Pauls and semihollows, like your ES-335. But Strat tones are all over the new album. That’s a new thing for you.

That was a blast, man. It’s not just a tone - it’s a direction. That’s the signature guitar tone for the record, if you ask me. I have a 1960 slab-board Strat that I got at Carter’s [Carter Vintage Guitars in Nashville], and it hadn’t been played a whole lot, so we had to do quite a bit to get it set up. Took a few months of moving and letting it adjust.

But there’s something about the out-of-phase position on a ’60 in particular, and I don’t know if it’s because the wind on the pickups was reversed from ’59 to ’60. It had a three-position switch when I got it, but I went ahead and put a five-position switch in so it would be easier, because I was getting tired of slipping out of the Knopfler spot.

I have a ’64 Vibroverb that Amanda got me for Christmas a few years ago that already had the [Cesar] Diaz mod, so the vibrato was disconnected. It’s the best-sounding amp that I have. We split that signal with, of all things, a 120- watt, solid-state Roland Jazz Chorus, and it was so clean and so bright and so present that it almost hurts.

If you’re going through a Jazz Chorus with a Strat, you better play the way you intend to play, because you can’t do any damn string rakes and make it sound cool, use the overtones or feedback - none of that. There’s nothing to hide behind.

Mark Knopfler was the first name that came to mind when I heard that tone.

It’s time for that to come back. I think what really kicked it off was The Highwomen album. I feel like Reggie Young was doing a Mark Knopfler impersonation on that first Highwaymen record [the 1985 debut release from Johnny Cash, Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings and Kris Kristofferson], because it sounds so much like Mark.

When the Highwomen recut the title track from Highwaymen [as “Highwomen”], it just made sense to try to play like Reggie Young trying to play like Mark Knopfler. Sometimes I forget how great Knopfler was at doing the thing I’m trying to do, which is write really beautiful songs and still find a way to use rock and roll guitar tastefully, technically and beautifully.

You acquired the famous “Red Eye” 1959 Gibson Les Paul last year. Did you give it a good workout on Reunions?

It has one standout moment on “What’ve I Done to Help.” The song is pretty long, and it comes in late for the slide solo. On “St. Peter’s Autograph,” I did some George Harrison–style parts that he probably would have played on Lucy [Harrison’s 1957 Les Paul gifted to him by Eric Clapton] back in the day. That’s a double-slide part, and we even did the Automatic Double-Tracking effect, like the Beatles used.

Listening back through your records, slide has been one of your signatures.

That’s the thing I’m best at. As a slide player, I feel like I have something to add to the conversation, at the very least. Like, I went to play on Tommy Emmanuel’s record [2018’s Accomplice One], and I said, “I’ll sing and I’ll play slide, and I’m not doing anything else. Anything else will just be you being nice to me.”

And that’s not to say that I’m even the best slide player on the street, but I feel like I can express myself in a way that’s individual.

Did any solos from cutting live basic tracks survive to the final mix?

“Overseas” was the take that I played live. I had a really fun signal chain on that one, too, because I got a ’58 Bassman from Rudy’s [Music, in New York City] last year that I think had been part of George Alessandro’s collection at one point, so it had all the work he had done himself to the amp, and it’s a killer.

It doesn’t have too much midrange honk. We ran a Strat through the Klon Centaur and into that amp, and, man, there’s some overtones on that solo that I don’t know how we got. Sometimes when I bend a note on the neck pickup on that Strat, you can hear another octave up.

Despite the beefed-up lead guitar presence, acoustic guitar is the backbone of Reunions. What did you gravitate to this time?

I believe it’s a Gibson J-35 but it’s a ’46, so it’s the year after the banner [headstock logo]. It’s basically the same exact guitar, but the banner is just not as expensive. But it’s this script logo, and I guess in ’47 or so they went to the standard Gibson logo that they still use today. But this is all over that record. I think this guitar is on almost every song, maybe with the exception of “Overseas.”

How did you develop the fingerpicking style you use on “Only Children”?

It’s really a hybrid thing. I can’t nail the Chet Atkins–Merle Travis style, because I can’t disconnect my thumb from the rest of my hand like those guys could. “Windy and Warm,” “Cloudy and Cool” and “The Bells of St. Mary’s” - that stuff was around the house a lot when I was a kid.

But I was always just too obsessed with rock and roll guitar to learn how to do it right. And when I got to Jimmy Page, it was like, 'Okay, I’m good.' I can figure out enough to make this work without learning how to do a proper alternating thumb.

On “Be Afraid,” there’s a chiming pattern on the verses that reminds me of Peter Buck with Mike Mills playing behind him.

Oh, yeah. The 12-string is Sadler. I think I played that alternating pattern on an early ’65 Tele, and then Sadler echoed that with a Rickenbacker 12-string. That’s a real Peter Buck style on that. He played some of the coolest guitar parts that are simple to learn once they exist, but not simple to come up with in the first place.

That was his trip. He never claimed to be a technical player, but you try writing something that cool. Even “The One I Love” - that is the simplest guitar part on earth, but nobody thought of it before he did.

With the guitars and amps you have at your disposal, you must have fun even during your downtime.

Whenever I don’t have anything else that I have to do, I play the guitar. Like yesterday: I had an hour between the time I finished doing everything and the baby woke up from a nap, so I sat down and played the guitar for an hour.

I just love doing that so much now - even more than when I was a kid, because I’ve got all the cool shit that I wished I had then. If I want to play Led Zeppelin riffs, I can play a 1959 Les Paul through a 50-watt Marshall turned all the way up. Nobody makes me stop.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Jim Beaugez has written about music for Rolling Stone, Smithsonian, Guitar World, Guitar Player and many other publications. He created My Life in Five Riffs, a multimedia documentary series for Guitar Player that traces contemporary artists back to their sources of inspiration, and previously spent a decade in the musical instruments industry.

"Jaco thought he was gonna die that day in the control room of CBS! Tony was furious." John McLaughlin on Jaco Pastorius, Tony Williams, and the short and tumultuous reign of the Trio of Doom

“It’s all been building up to 8 p.m. when the lights go down and the crowd roars.” Tommy Emmanuel shares his gig-day guitar routine, from sun-up to show time