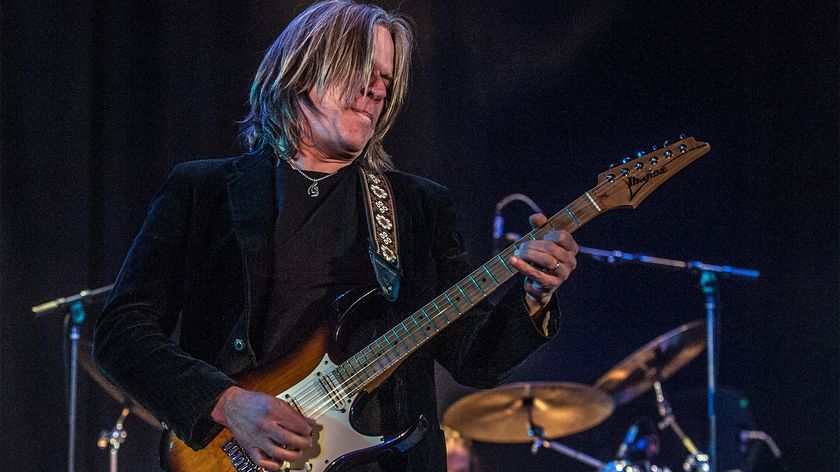

“Led Zeppelin? Not Something We Grew up Listening to”: Jake Kiszka Talks Hot Gear, Vintage Tone, and What Everyone Gets Wrong About His 1970s Hard-Rock Renaissance

Since Jake Kiszka burst on the scene six years ago with his hard-rock band Greta Van Fleet, the 27-year-old guitarist has captured the imagination of six-string fans and fellow players like few of his contemporaries. His adventurous and sophisticated approach to the guitar, much of it based on the traditions of blues and classic rock honed decades before he was born, has made him the preeminent axe hero for his generation. He’s topped readers polls – Best New Guitarist, Best Rock Guitarist, Best Guitar Solo... You name it. It’s enough to make any young player’s head swell, but Kiszka seems to be taking the acclaim in stride. When asked to explain why so many guitarists are drawn to his style, he addresses the topic thoughtfully.

“I do seem to encounter a lot of people who admire my playing,” he says. “They tell me that my type of playing is a lost art form. It’s like I’m a relic – my approach to playing is something from the past.” He chuckles at his own words. “I think people appreciate the way I embraced that tradition and evolved it to the contemporary world. I think there’s a lot of soul in what I do. I mean, people have said that they can feel my soul when I play. They appreciate that I’m trying to communicate.”

From all appearances, Greta Van Fleet – which includes Kiszka’s brothers, lead singer Josh and bassist-keyboardist Sam, along with drummer Danny Wagner – has caught all the breaks any modern-day rock band could possibly desire. They went gold with their first album, 2018’s Anthem of the Peaceful Army, and their 2021 follow-up, The Battle at Garden’s Gate, hit the upper regions of music charts across the globe. Their live shows grew from small clubs to bigger clubs, and it wasn’t long before they were packing theaters and sheds. This year they’ve graduated to the league of bona fide arena headliners, so it would seem when it comes to rock and roll bucket lists, the group’s members just might check off every item before they reach the age of 30. It’s enough to make Kiszka’s head spin.

“I can’t explain the success we’ve had, to be honest,” he says. “I think people are responding to our authenticity, which stems from our influences and what we grew up with. The purity of it and the truth of it resonates with people.”

New York City’s Madison Square Garden is one of the venues on the group’s 2023 itinerary. Kiszka’s eyes light up and his face fills with a sense of wonder at the very mention of the hallowed concert arena. “I was thinking about it at breakfast the other day,” he says. “I remembered how, when I was a kid and I wanted to be a guitar player, it seemed like every big band played the Garden. Cream and Zeppelin, the Who – the endless list of rock royalty. Then I realized that I’ll be playing Madison Square Garden. I’ll be walking in the footsteps of all those who’ve influenced me.” He smiles. “Madison Square Garden… It’s like the Garden of Eden.”

Greta Van Fleet appear to have nailed yet another rock tradition: The bigger they get with the public, the more critics have it out for them. When they arrived out of Frankenmuth, Michigan, with their first recordings – a pair of swaggering singles, “Safari Song” and Highway Tune,” followed by an EP, From the Fires – they elicited comparisons to Led Zeppelin, and rightly so: Every element of that group’s sound– from Robert Plant’s siren-like wails to Jimmy Page’s blues-drenched solos and John Bonham’s thunderous drum attack – seemed to have been re-created with uncanny, reverent precision. But as Greta Van Fleet strove to expand their sound on subsequent releases with splashes of country-folk, psychedelia, progressive rock and even hints of world music, the critics came at them with sharpened knives. In its review of The Battle at Garden’s Gate, entertainment-trade mag Variety likened them to Spinal Tap.

For his part, Kiszka dismisses the barbs like he’s swatting away a pesky fly. “I don’t think criticism has ever affected us,” he says. “It’s ponderous and intriguing to presume that somebody has spent time and energy to say how they’re indifferent to us or don’t like us, while we’ve put zero energy into caring what they think.”

He gives hosannas as much attention. “The praise rolls off our shoulders,” he says. “We’re musicians and artists, and if we’re to achieve any kind of perfection, then we have to let go of any sense of ego. It destroys talent. We’re always striving to be better musicians, and I’m striving to be a better guitarist. If I allowed all of that praise to go to my head, I’d be stagnant.”

Greta Van Fleet’s new album, Starcatcher (Lava/Republic), doesn’t depart from the band’s classic rock-based style – if anything, the group turbo-charges each tried-and-true component and drives it home. The set’s first single, “Meeting the Master,” begins as a contemplative, acoustic-laced ballad that explodes into a frenzied rock monster.

Similarly, the band eases its way into high-minded, trippy mood pieces like “Waited All Your Life” and “Farewell for Now,” drizzling bits of pastoral folk and spacey prog flourishes, before Kiszka flips a switch and takes off with brawny, go-for-the-gusto solos. While nothing on the record comes close to the nine-minute “The Weight of Dreams” (from The Battle at Garden’s Gate), each song feels like an epic, and Kiszka makes crafty use of every passage, layering elegant, arpeggiated lines and swooning leads between the various big spotlight moments. Sometimes the band needs no time at all to land a punch: On the aptly named “Runaway Blues,” they temporarily ditch their mystical shtick and blaze through a delirious rave-up that’s over in but a minute and a half.

The band relocated to Nashville several years ago, and for Starcatcher they tapped that town’s resident hitmaker, Dave Cobb (Brandi Carlile, Jason Isbell, Rival Sons and Grace Potter, among others), to produce. “Dave’s name was always on our radar,” Kiszka says. “He’s come into the scene as a prominent producer of rock and roll groups. We were like, ‘Is that a good thing or a bad thing?’ Maybe it would be stereotypical, but it was something we wanted to explore, regardless.”

A meeting between Cobb and the band went well, but Kiszka reveals that the members decided to “date” a few other producers before giving Cobb the nod. “In the end, we decided to marry Dave,” he says with a laugh. “It became obvious that he was going to be the one to help us create this record. It’s very challenging for producers to work with such a tight-knit group as ours. We speak the same language, and producers have to pick up on that vernacular. With Dave, it was easy because he shares our influences. He fell in seamlessly.”

In terms of technique, there are many styles of contemporary guitar playing that have been seamed into my matrix

Jake Kiszka

You’ve never tried to hide your affinity for rock music from the ’70s. And, of course, some of the criticism you’ve endured is that you simply rehash that music. How do you think you take that influence and try to update it?

I believe our evolution, as well as my own progression, has always been a product of a contemporary world. A lot of the music and guitar playing which I’ve studied comes from a bygone era – the golden age of rock and roll. I’ve taken that heavy, guitar-based music and attempted a new approach, by giving it a modern perspective.

Can you elaborate on what that “new approach” means?

In terms of technique, there are many styles of contemporary guitar playing that have been seamed into my matrix. It’s an evolution of time and music; as the genres have progressed, so has the guitar playing. The sonic approach is complex and dynamic, because over the passage of time and technology, especially in terms of the studio, it has also advanced. This includes utilizing different microphones and different pedals, as the world of pedals has evolved as well. Given that expansion, I think a lot of the usage of those technologies has brought an absolute new and modern sonic approach to my guitar playing and our music.

The way I tend to write is coming from a very modern perspective. There have been many songs written since the advent of rock and roll until 2023 that observe the form of writing and its development – it’s come a long way. Let’s say if you’re using a 12-string in DADGAD, as opposed to a parlor guitar in standard, you’re going to hear and see an extraordinarily different outcome.

Obviously, you and your brothers share the same influences. Can you speak to the innate connections family musicians have when they play together and how they inform the music?

Yeah. I think we have this sense of reinforcement of what we’re doing. It’s a pretty complex undertaking to communicate in general, as human beings, but on an instrumental level it’s an even larger feat. I think the fact that we all grew up together has certainly solidified our communication as musicians. When we’re onstage and we’re playing our instruments next to one another, it’s a form of communication. We understand each other’s nuances. We don’t like to play songs the same way each night. We like to jam and improvise.

Let’s pick up on that. When you jam – that is, when you’re not writing songs – what do you like to play? What’s a typical night like in the Greta rehearsal room?

It’s great. It’s everybody getting together and pulling out a bottle of tequila. I’ll show up last. [laughs] We’ll just kick it out. Even at soundchecks, we’re always playing. It goes back to that form of communication. Somebody will start playing something, and then somebody else will walk in the room and start playing.

I think the fact that we all grew up together has certainly solidified our communication as musicians

Jake Kiszka

But what are you jamming to? Original tunes? Covers?

A little bit of both. Usually, it’s original jamming, but other times I’ll have learned something. “Rock ’n’ Roll Ain’t Noise Pollution” by AC/DC is something I just learned. I always liked the song and pulled it out. We all started playing it. You don’t have to rehearse for something like that. But it’s usually original stuff – that’s how it works in the studio.

Was the Starcatcher track “Runaway Blues” a jam? It sure sounds like it.

It was a jam in the studio. We were having a slow, sort of methodical day, and I just wanted to rip out something new. Nobody was around, so I started playing that riff. Danny and Sam came in, and we finished a take of another song. Then I kicked off with the riff. Dave Cobb started freaking out: “That song needs to be on the record!”

I have praise, and a complaint. I absolutely love the song, but I was bummed when you faded it so quickly.

Yeah. The reason why it’s so short is because Josh didn’t like it, and he wanted it to be brief. I think there’s an aspect to the song – you end up wanting more.

Van Halen used to do that. They would feature these awesome bits of rocking on their records that lasted only seconds.

Yeah. That song is part of the whole web of the record. It adds a lot of energy. It’s something that we may extend live. We like to do that sort of thing.

Not to belabor Led Zeppelin, but as you know, the critics do bring it up a lot. I wonder, is there something they’re not seeing? What influences are there that they don’t pick up on?

It’s pretty broad. The complexity of musical influence and the depth of that is extreme within the group. But it’s really everything – there’s not a lot of music that we dislike. We grew up with roots music. As for Led Zeppelin – we weren’t listening to rock music growing up; that happened in high school. So we’re talking about the originations of the genres that we now consider to be folk music, like Woody Guthrie and Bob Dylan. We had Alan Lomax records laying around. It was roots of the Great American South and the Blue Hills – bluegrass music and banjo playing.

And it goes into blues music and Native American music. People don’t know that we grew up with some Native American music, which was informed by blues. So you’ve got Robert Johnson and Charley Patton, Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters, Albert King, John Lee Hooker and Son House – all of these collective blues influences. We saw our way into all kinds of stuff, even classical music like Frederic Chopin and Mussorgsky, Bach and Beethoven. We listened to Peruvian music growing up.

The complexity of musical influence and the depth of that is extreme within the group

Jake Kiszka

So the influences go beyond Zeppelin.

Yeah. Again, it’s pretty broad. And pretty extensive. Obviously, this could be a very complex answer, but these are just examples.

During the period when you were absorbing music and forming your style, was there a cut-off period for you? When you first heard what we call “shred,” did you say, “Not for me”?

I was never a big fan of shredding. It didn’t really interest me because I didn’t hear the soul and dynamics of an earlier style of guitar playing. When Jimi Hendrix played guitar, you could feel the soul coming out of his body. That moment right there probably defined my direction and approach. For me, shred music didn’t achieve that sort of thing.

We wouldn’t necessarily put Eddie Van Halen in that category.

Eddie Van Halen is an outlier. I like his approach – he inspired and created a type of music, but there was enough nuance in what he was doing that you could still hear a human element. Nowadays, the amps are so cranked and there’s so much gain and distortion. It’s less like painting and more like digital art. It’s like A.I. versus human art.

Moving forward, would I be right to assume that something like the djent movement didn’t hit you at all?

It does a little bit because, as a guitar player, I appreciate that it’s a duality of many different styles and genres and instruments. Even in, for instance, the eight-string guitar or something.

Would you even know what to do with an eight-string guitar?

I would have to figure it out. As a guitar player, it’s interesting to see the depth of complexity that people have brought in over time. Leo Kottke would be playing a 12-string steel guitar with a slide, so that’s three elements that are very interesting that you wouldn’t necessarily combine. But he did it, so we have that.

On this new record I toyed with new techniques and tunings. I used a B-Bender on “Fate of the Faithful.” “Falling Skies” is in DADGAD, “The Archer” is in open C, and “Meeting the Master” is in some strange tuning I made up – it’s a full step down, and then you drop the bottom D one more step. It’s crazy. And I was using a Taylor baritone that had two B strings. I tried toying with different sounds.

Did you try soloing outside of the minor pentatonic scale at all?

Sure. There are blues boxes, which are extremely helpful to me. It’s just a variation of the pentatonic scale from the base of the neck all the way up to the top. There are other phrases and movements inside of that, and you can configure them all the way up and get into Dorian-like scales. If you’re soloing in an open tuning, that’s completely instinctual. You just find what feels good and play those notes. It’s good to try open tunings.

I still don’t practice. My practice is on the stage or when I’m writing songs on a guitar

Jake Kiszka

A few years ago, you told me that you don’t really practice. Is that still true?

I still don’t practice. My practice is on the stage or when I’m writing songs on a guitar. In that sense, it keeps things frustrating. If I practiced all the time, it would be, for me, probably a moot point being that it’s not really my form of expression.

Back to your record. During the planning stages, did the band sit down and map out an objective, or did the album just evolve as a natural outgrowth of the songs?

There was a certain set of objectives that we had. We came out of our last record thinking we created this cinematic, almost orchestral record. On this one, I wanted to do something fairly aggressive.

In what way?

In terms of the emotional approach. Many of these songs are intense both emotionally and sonically. We also wanted to have a lot of dimension within the dynamics of our performances. Between “Meeting the Master” to “The Falling Sky” to “Farewell for Now,” the range is pretty diverse. Once we had those concepts in mind, it was really just going out and isolating ourselves in the country and writing these songs in two weeks. Then we went to RCA’s Studio A and recorded them.

Where exactly did you go to isolate yourselves?

We went to a cabin just south of Franklin [a city south of Nashville]. We brought all of our gear and set up – that’s how we like to operate. We like to get out of any city and be in the middle of nowhere, and live and breathe what we’re doing every day.

Was there anything significant in Dave Cobb’s method of recording that had a real impact on you?

It was a maximum impact. Most people set a mic right next to an amplifier and go, “There’s your sound.” But you and I know that the technique is to pull that mic away and get the ambience and the live sound. Dave would set the mic 10 feet away, but then he’d listen back and go, “Nah, it just doesn’t sound right.” It would sound bigger at 12 feet. We did a lot of stuff with delays and things like that.

Dave got things sounding so good that I didn’t have to worry about it. That was a big part of his impact. We didn’t have to worry about the sound; we only had to think about the music we were writing and how we were going to perform it. Our attention was right where it needed to be.

This record is like your others in that you didn’t use generic, dialed-in distortion. Your sound is big and powerful, but there’s a natural element to it.

Yeah, again, that’s a huge thing. Most players tell me that I play very clean. I do, I think, but I like the nuance of that style. You can hear the detail of my playing; you can hear the complexities of it. I can whisper something or I can profess it loudly from the top of a mountain. I have the ability to work with dynamics in terms of tonality and approach, and I like that.

What was Dave like as a guitar coach? I don’t assume everything you come up with is awesome right off the bat. When you played a part and it wasn’t quite right, how would he guide you?

It’s interesting: If I had a pre-chorus or something, he’d go, “That’s cool.” Luckily, he likes everything I do. But sometimes he’d say, “That pre-chorus is great and I like it, but it sounds really complicated. What if you simplified it?” And I’d say, “Okay, I can do that.” That’s the thing – he’d be into what I was doing, but he’d want to go more in this direction or that. I would just revise it.

It’s difficult for us as human beings to identify our growth within ourselves. It’s the same thing with my guitar playing

Jake Kiszka

Do you ever get bruised feelings in the studio? What happens if you play a part that you think is awesome, but you get criticism?

It has a lot to do with the producer. I’ve been hurt by constructive criticism in the past, but Dave works in a way that isn’t offensive. It’s not like, “Go rewrite that part. It’s shit.” Because I’ve had that way back, which was fine – I needed it then. Dave never changed anything that I wrote, but he made me utilize those notes and make a variation of it.

Beyond some of the new tunings and techniques that you’ve mentioned, do you feel like your overall guitar approach has changed in recent years?

I don’t think so. I’ll put it this way: I believe that every season changes who I am as a person, and that influences the way that I approach the guitar. I’ve played a lot of shows, and I’ve taken different approaches to the guitar both consciously and unconsciously. It’s like a personality or a spirit – it evolves with time. It’s difficult for us as human beings to identify our growth within ourselves. It’s the same thing with my guitar playing. I’m not sure how it’s evolved, but I feel like it grows as I grow.

One of my favorite solos is on “Frozen Light,” where you go absolutely bonkers. Was that done in one take? It doesn’t sound like something you played to death.

Yeah, that was another thing Dave brought to the table. I was like, “I want to take that solo again.” And he said, “No, you can’t take that solo again. That’s the solo.” The “Frozen Light” solo is probably a second take, I think. I don’t think I played any solos or improvisations more than five times.

You favor your ’61 Gibson SG, but what were some of the other guitars you used on the album?

I used that ’61 SG number one for the majority of some basic structures, but I used more guitars on this record than on anything else in the past. The RCA studio room is really big, so we took all these guitars off the wall. A friend of mine who owns the Chicago Music Exchange brought a bunch of guitars down. We laid them out on the floor, opened them up, and with every song I’d walk over and get another one to see how it sounded.

What were some of the guitars that made the cut?

There was the third ES-335 ever made – it had some country stars names on it. That one outshot all the other ones for a lot of things. It was amazing. There was a ’60s Telecaster. It’s challenging to remember all of them. Dave has his ’58 gold-top – I used that. There was a Stratocaster that I used for dive bomb– type sounds and stereo things. The acoustic world was crazy, too. We’d use old Martins and a lot of things like that.

Did Dave break out his nylon-string acoustic? I was talking to Grace Potter, who told me that she played that guitar and didn’t want to give it back.

Yeah, I wanted to steal it, too. Actually, I used one of his Princeton amps and fell in love with it. I was looking for one at some guitar function in Nashville, and I bumped into Dave. I told him what I was looking for, and he said, “Oh, man, you can have it.” Just like that, he gave it to me.

Have you decided on which guitars to use live?

I’m going to need a few more. I’m looking for some to replicate the parts on the record because of all the alternate tunings. I found this old Frankenstein Telecaster and I brought it to [guitar luthier] Joe Glaser. He put a B-Bender in it. So I’ve got that little creation to help me play “Fate of the Faithful.” I’ve still got to find some more guitars.

I was put in touch with Peter Frampton, and I talked to him about his wet/dry rig

Jake Kiszka

You mention the B-Bender. Did it take you a while to get used to playing with one? How did you approach it?

To be honest, it came rather immediately. I understood what was going on, and I didn’t really have to think about it. It came pretty naturally to me. Using it inside the solo of that song, as a technique within the soloing, was something I’d never heard before. I had to do it because it was totally weird and different. It’s a dance, the way you have to use it.

What about your live rig? Any changes to that?

I certainly might use the Princeton amp. I’m working out a wet/dry system right now. We’re playing these really big rooms, so I don’t need the reverb stuff that I’ve always had. I need to be clearer to cut through these arenas. I was put in touch with Peter Frampton, and I talked to him about his wet/dry rig. He’s really well versed in that system and how it works. He gave me some tips, and I think he’ll probably come by production rehearsals and help me get this wet/dry thing going.

Peter is a lovely guy.

He really is. He’s the kindest soul.

We started out this conversation by talking about how your fellow guitarists have responded to your playing. You’re now being called a guitar hero. How does that sit with you? How do you feel about it, and in your view, who is a guitar hero?

That’s kind of a broad concept. It seems to be a tradition, doesn’t it? There are generations of players who become icons of their times. You can go back to the British Invasion and people like Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, Jimmy Page... And then there’s Jimi Hendrix, Pete Townshend, Rory Gallagher – these people became figureheads. Move it further and you’ve got Stevie Ray Vaughan and Slash. They all inspired me. To be considered a guitar hero for my generation is a lifetime achievement.

Order Greta Van Fleet's Starcatcher here.

Visit the Greta Van Fleet website for tour information, merch and more.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.