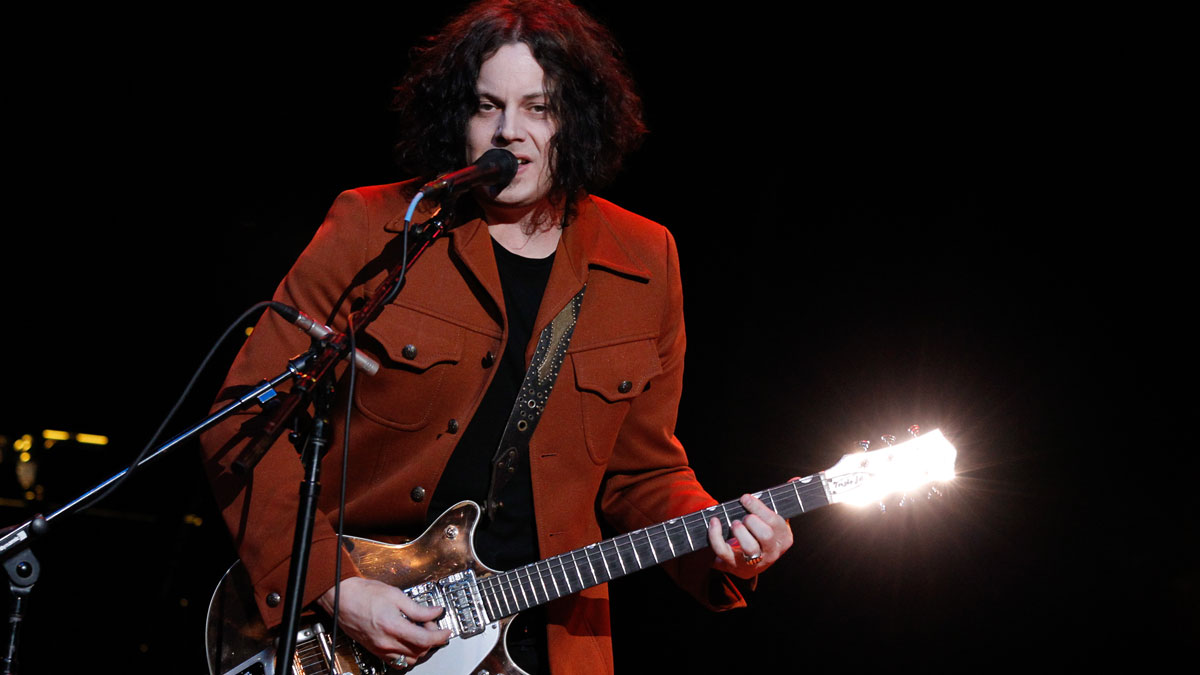

Jack White On The Sounds That Drive The White Stripes Raconteurs and Dead Weather

The modern blues guitarist par excellence on his pawn shop guitars and tonal approach.

Jack White is no shredmeister, and he's not the most melodic guitarist on the planet, either. Yet despite being a less-than-obvious extension of the guitar-god tradition, this scrapper from Detroit has become the heavyweight champion of rock guitar over the past decade.

The gifted multi-instrumentalist has garnered an astonishing track record of commercial and critical successes by landing a succession of insanely catchy hooks, never compromising his strategy, and matching a wild-eyed knack for sonic ingenuity with sheer intensity.

“I always look at playing guitar as an attack,” says White. “It has to be a fight. Every song, every guitar solo, every note that’s played or written has to be a struggle. It can’t be this wimpy thing where you’re pushed around by the idea, the characters, or the song itself. It’s every player’s job to fight against all of that.”

White has been a soldier for the cause since at least 1997, when he formed the White Stripes with drummer Meg White. Actually, White’s original instrument was the skins, as well. But when he traded his sticks for a Ward’s Airline guitar, and pumped it simultaneously through a vintage Silvertone and a Fender Twin, the duo struck a raw nerve. The White Stripes’ minimalist garage blues was both original and traditional, and the band’s unique sound spawned myriad groups populated by players who were sick of slick audio production and homogenous guitar tones. White embraced his twisted blues roots in a big way on Elephant, which he dubbed his “guitar” album in his June 2003 GP cover story. Elephant’s first cut was a doozy. The bombastic “Seven Nation Army” was an instant rock classic, whose main riff ultimately became a sportsstadium anthem.

When the red, white, and black box that White created for the Stripes got too limiting, he proved he was more than a one-trick pony by appearing in and contributing tracks to the Civil War film, Cold Mountain, and producing— as well as performing on—country legend Loretta Lynn’s lauded comeback album, Van Lear Rose. White enlisted Greenhornes bassist Jack Lawrence and drummer Patrick Keeler for the Lynn sessions, along with fellow Motor City tunesmith Brendan Benson to help engineer. When White and Benson found themselves in need of a rhythm section for a little song they had written together called “Steady As She Goes,” Lawrence and Keeler answered the call once again. In 2006, that song became the debut single from a band that would co-exist with the White Stripes, the Raconteurs.

When the Stripes dropped Get Behind Me Satan in 2005, the deep guitar riff and falsetto vocal of “Blue Orchid” sounded downright demonic, but much of the record featured White on piano and marimba, and not playing big guitar. But 2007’s Icky Thump was aptly named. The title track’s Zeppelin-inspired riffs and plodding bass drum absolutely invited the masses to raise their horned hands in head-banging approval. White then found himself face-to-face with riffmaster Jimmy Page when the two participated in 2009’s It Might Get Loud—an insightful, must-see film directed by Davis Guggenheim (who also directed An Inconvenient Truth) that documents the careers of White, Page, and The Edge.

The White Stripes’ 2007 Canadian tour is featured on Under Great White Northern Lights—a DVD and CD release (also available as a limited-edition box set that contains the DVD and CD and other goodies for die-hard fans) that celebrates the band’s decade of live performing with rip-your-face-off footage of the duo kicking out their most signature jams, as well as impromptu performances shot at unlikely venues such as a bowling alley and a boat.

Meanwhile, White launched a dark and heavy outfit called the Dead Weather. An allstar affair featuring Alison Mosshart (the Kills) out front, Dean Fertita (Queens of the Stone Age) on guitar, and Jack Lawrence on bass, the Dead Weather puts White back where he began—on drums. GP caught up with White before the Dead Weather took the stage for a pair of sold-out shows at the venerable Fillmore auditorium in San Francisco.

It’s unusual to interview you for a Guitar Player cover story when you’re technically the drummer for the Dead Weather tonight.

I’m more of a drummer now than ever before. I play drums throughout the new record, whereas I only played guitar on two or three songs. Dean is the primary guitar player in the Dead Weather, but we all switch instruments regularly. Everybody in the band plays guitar on one track or another.

Still, your sonic imprint is all over the album.

Well, I produced and recorded it in my studio, so the Dead Weather is really part of the Third Man Records sound that has evolved over the last year-and-a-half, since we opened the new headquarters in Nashville. I’ve been attacking things not just as a guitar player, but also as a drummer, and by doing a lot of the production, as well.

You probably have the most identifiable sound of any player over the last decade. Could you talk about your sound, and how you capture it?

I feel as though I’m breaking through something when I play the guitar onstage or in the studio. Like punching through a wall, or trying to climb on top of something, and then destroying it. That’s the goal from plugging in—even if I’m playing a gentle song. Your tone alone can speak volumes for you. You can also make a statement without over-thinking it. It’s hard to relate that to modern guitar players, though, because they put too much gear between their fingers and the amp. Too many players feel their effects are supposed to craft their tone for them. It really comes from the fingers, of course. For example, the idea behind using the Ward’s Airline in the White Stripes was to prove that you don’t need a brand new guitar to have character, to have tone, and to be able to play what you want to play. You can do it with a piece of plastic, or a piece of wood. You see, you can buy a bunch of fancy equipment, but if you don’t have “it” inside you from the get-go, you’re not going to impress anybody.

What’s constant about your approach, even if you’re playing a gentle song?

I always think playing gently is a tactical move. You’re sneaking up, and then you’re going to attack. People are waiting for that. Jeff Beck is a great example. I’m constantly waiting for him to attack his instrument. Blind Willie Johnson is another. I could care less if he’s playing the right notes, or if his guitar’s in tune. Attack and attitude speak volumes.

Can you break down your attack?

For years, I didn’t want to do any downstroking at all. I always wanted to do upstrokes because I got a more striking note every time. I still revert to that technique most of the time when I’m playing. In the White Stripes, though, I started to develop a subconscious style of playing lead and rhythm at the same time—back and forth, back and forth. I started hiding my pick under my finger to switch quickly to fingerpicking, and then back to playing with the pick. I didn’t even realize I was doing it that way for years, because form follows function. If something needs to happen, your body and brain will make it happen. If your pick ends up in your ear, or underneath your eyelid or something, it’s because it needed to happen.

What about your left-hand technique?

The first thing to know about my left hand is that I had to relearn how to play with these three fingers [holds up fingers two, three, and four]. In 2004, I was in a car accident, and the airbag shattered all the bones in my index finger. It won’t close anymore—that’s as far as I can go [makes a “c” shape].

So you can’t literally make a proper barre chord anymore?

I used to play A minor with my first three fingers, but now I use fingers two through four. My index finger hangs out doing nothing most of the time. I can do barre chords with it now, but I can’t play a C, or a D minor with that finger. It’s become dead to me in a lot of ways. The first couple of shows were really rough. I was actually trying to play right after the car crash. I was three blocks from my house, and I went right back inside and grabbed my guitar to see if I could play well enough to tour. But I couldn’t. I had to cancel all the shows to recover. It took many months, and I had to have surgery.

How do you make that sliding sound without using a slide?

I don’t really know what it could be. Maybe I go up to attack the note. Also, I like to manipulate my DigiTech Whammy pedal starting with the low octave. I love low octaves. I’ve always loved playing octaves on the piano, even as a little kid. So when they came out with that pedal, and I heard Tom Morello use it in Rage Against the Machine, I knew I’d finally found an interesting pedal. All I used in the White Stripes for seven years was an Electro-Harmonix Big Muff and the Whammy. So you might be hearing me building up to the note with the pedal.

Okay, how about some actual slide-playing tips?

It’s better to play slide with the pinky finger. That way your first three fingers can mute the strings behind it, and then you don’t get all that metallic rattling. You can focus solely on the note you want, which is more like a pedal-steel technique. A lot of people put it on their middle finger, and they’re missing that idea. You may get better control from one of the thicker fingers, but the pinky’s the way to go if you want to kill all the extraneous noise.

What are you playing tonight with the Dead Weather?

I had all of the Dead Weather’s equipment custom made. I co-designed the drum set with Ludwig. Gretsch painted all the guitars white. I was going to do shows with Alicia Keys and the band for the James Bond theme I was working on [“Another Way to Die” for Quantum of Solace], but I slipped a disc in my neck, so I couldn’t. As a result, all the equipment I had designed was just sitting in my studio. When the Dead Weather started, it was just supposed to be a 7-inch single, but it turned into an album, and then into a band. So I said, “This equipment is already here. We should use it.” The gear ended up influencing the band’s overall color scheme. I play a special-edition Gretsch White Penguin Jupiter Thunderbird. They only made 12 of them, and I found one in Texas. I also got a Gretsch Bo Diddley factory model, and painted it white so that Alicia Keys and I could be like Bo Diddley and the Duchess— his female stage partner. We would both use those guitars on tour to support the James Bond theme. But when I got hurt and I couldn’t do the dates, Alison [Mosshart] ended up taking on that idea. She plays the rectangular Bo Diddley model, and I play the Jupiter Thunderbird—which is also called the “Billy Bo” because Billy Gibbons brought that idea back to Gretsch.

What’s your Dead Weather rig, and how does it compare to the White Stripes rig?

The amp is a Fender Twin Reverb—no Silvertone, like in the White Stripes. Effects-wise, I have a Big Muff and a Whammy just like in the White Stripes. Sometimes, I use a POG pedal. I think I was the first person to record with one on the White Stripes song “Blue Orchid.” Electro-Harmonix sent me one as a present when we were recording Get Behind Me Satan. “Blue Orchid” came out two weeks after the session, so it had to be the first song to feature the POG. I use it to add the first and second octaves below, and one octave above the root note. It’s four of the same note simultaneously. It’s just so heavy. The riff is actually pretty simple, but it’s all about the one. It’s a funk-based idea.

What picks do you prefer?

Any heavy pick, so I can strike the string harder. Anything other than a heavy gauge just feels wrong. I end up throwing it away, and plucking with my fingers.

What brand?

I don’t know. Whatever company can make black ones [laughs].

What kind of strings do you use?

I really don’t know. When I was a teenager, I used GHS strings because I was from Michigan, and they were made in Michigan. I liked the nickel ones because they sounded a little bit different. But I stopped caring when I was 19 or 20 years old. Everyone always asks, “Do you like .009s or .010s?” I have no preference, because I can’t decide if I want to make it easier or harder on myself. I usually choose to make things harder on myself, but I don’t know when it comes to strings. Lighter strings might actually be harder for me to play, because I hit them so hard. I bend them too easily, and break them all the time. I leave it to chance. I always just tell whoever is putting the strings on to do whatever they want. I won’t even notice.

Do you have any endorsements?

No. I have never endorsed a product.

Is that a general life stance?

I feel better about paying for my gear, because I don’t owe anybody any favors. People come up and say, “Here, you can have this guitar for free.” I’ll say, “Okay, thanks.” And they’ll say, “Can we take a picture with you holding it for the Web site?” I’ll just hand it back to them [laughs]. It’s like, “Well, that’s not free then, is it?” Also, most of my favorite brands—such as Silvertone, Airline, Supro, and Bigsby—are gone. I prefer old Gretsch guitars to new ones, but Gretsch still has the best sounding new acoustics and electrics. They have a lot more character and quirkiness than other modern guitars.

What acoustics do you prefer?

Gretsch Ranchers. They are great for live use, because they produce more bass than anything else, and I like a lot of bass in an acoustic guitar.

How do you amplify them?

Playing an acoustic live is very difficult— especially when everyone else in the band is playing electric. It’s very frustrating. I don’t have any advice, other than it’s tough, and the best thing to do is stand really still and put a microphone in front of the soundhole.

Who are the women portrayed on the backs of the Ranchers?

Claudette Colbert is on the orange one I used in the Raconteurs and White Stripes. Rita Hayworth is on the white one you see me carrying around in the Great Northern Lights DVD. The white and gold one I use in the Dead Weather has Veronica Lake on the back. So I’ve got a brunette, a redhead, and a blonde—one for each band. An incredible tattoo artist in Cincinnati, Ohio, named Kore Flatmo did the work for me. I saw the portraits he had done tattooing, and I bought him a really nice wood-burning tool to burn those images into the backs of my guitars.

Can you list the White Stripes guitars over the years?

I had the same three guitars in the White Stripes for about ten years: the Airline, a hollowbody Kay tuned to open A for slide playing, and a red Japanese guitar I used for open-E tuning on a couple of early songs such as “Let’s Build a Home” and “I Fought Piranhas.” Around about 2007, I got a ’57 Gretsch White Penguin, which is really rare.

So it debuts on Icky Thump?

Yeah. I always thought it was a really interesting instrument. One came up for sale in Nashville where I live, and I went and looked at it three times. I just didn’t know if I could justify buying it for a while. Finally, I was with some friends, and I said, “I want to go check that thing out again.” They said, “Alright, this time you’re buying it.”

How does it compare to playing the Airline?

It feels like it’s in the same department. It’s a very strange instrument. It’s more like a machine. The knobs are so clunky. Pickups don’t really sound like that nowadays—guitars don’t really sound like that.

When I saw you at Jazz Fest in New Orleans a couple of years ago, you had a copper-top guitar.

I had a couple of guitars made for the Raconteurs. I designed a Gretsch “Triple Jet” by adding a third pickup to a Double Jet, and putting an MXR Micro Amp inside the guitar. You can instantly get an overdriven sound by clicking on that pickup. You can just plug into an amplifier. If it’s time to play a solo and break out a little more, just click that switch on the guitar. I had everything for that band made out of copper. All the pedals were made of copper. I had a copper microphone, and I had the guitar made of copper. We even went as far as putting copper frets on that guitar—just to see how it sounded. It sounded incredible! But copper is so malleable that the frets wore out after one show.

Why copper?

I’ve always loved elements, and breaking things down to a single element—no other components. Sometimes, I need something to keep myself centered. Having everything in the White Stripes be red, white, and black centers me, and keeps me on that one path. Copper centered me on the Raconteurs.

Is Randy Parsons—the luthier who appeared in It Might Get Loud—still doing your custom work?

Yes. I do a little bit at home in Nashville with some other people, but I send all my custom ideas to him, and he brings them to life.

What’s up with your guitar that has a builtin microphone?

That was created for the Raconteurs, as well. I call it the “Triple Green Machine.” It was based on the “Triple Jet” idea with an MXR Micro Amp wired to the middle pickup, and then I added more and more things. I started with a Gretsch Anniversary Jr., which was the only small hollowbody guitar I could find. I made it a double cutaway instead of a single. I had a Bigsby installed, and I put in an old mute, too. When you pull a lever, the mute comes up and dampens the strings. I also had a light-activated Theremin installed that I could control with my wrist while I was playing. When I lifted my wrist, the Theremin would be added to the sound. I wanted to be able to pull a Green Bullet microphone out of the body, sing into it, and have it retract when I dropped it. Randy found a vacuum cleaner retractor cord for that. He built a fake Green Bullet—a wooden one, because the metal one was too heavy to retract. It took a lot of experimenting. The guitar weighs more than a Les Paul because of all the components!

I’m sorry you didn’t get to do the “Bond band” with Alicia Keys. “Another Way to Die” is the coolest James Bond song since “Live and Let Die.” How did that go down?

I wrote and produced it. She came to Nashville and sang it. We snuck it in at the last second. If they had more time to think, I don’t know that they would have approved the song for the film.

Did you write the song specifically for Quantum of Solace?

Yes. I was given the task to write and produce the song—which has only happened a couple of times since I began writing. I wrote it on piano first. I like to write on other instruments, and then transfer them to guitar.

Did you watch James Bond movies all day to get into the mind frame for “Another Way to Die?”

When I had the track going, and I began adding other elements, I actually did put Goldfinger and Thunderball on a TV screen in the control room with the sound muted—just to watch the figures move. I worked a lot on making it powerful and slow.

From watching the Northern Lights DVD, it looks like you are still using a Silvertone 610 combo and a Fender Twin Reverb.

That’s so I get the crunch and the reverb at the same time. The Silvertone’s reverb is horrible, so I just use it for the thick, Jensen-speaker crunch that only a Silvertone can produce. No other amp can sound like that. I use the Fender for the reverb. It’s the best. A Silvertone and a Fender make a great combination.

How did you get the tone for the ascending riff on “Icky Thump”?

That’s the POG.

How did that part of the track go down in the studio?

That was unusual. I said, “Roll the tape, I just thought of something.” I recorded Meg and myself playing that little five-second section, and then we sliced the tape and edited it in during mixing.

After the last verse and riff on the DVD version, you achieve a sound like a motorcycle revving up. There is also some sick-sounding octave stuff on the solo. How do you play and manipulate your effects to manifest such insane tones?

It all depends on what signal you give to the Whammy as you’re manipulating it. That might have just been a lot of open strings—something like that can really rattle as you’re diving all the way up. But you need a lot of gain and distortion to make that kind of tone. It sounds really wimpy if you don’t have some power behind the note. And you have to put the Whammy after the Big Muff in the signal chain. The power has to be before the octave.

You know, I actually started using the Whammy because it was a great way to cut through when I was playing in garage-rock bands in Detroit. We were relying on sound guys who didn’t know when to turn you up, so no one’s solos ever stood out. I thought, “If I hit the octave higher, there’s no way they’re going to miss me now [laughs].”

You play “Seven Nation Army” on your old Kay hollowbody slide workhorse, tuned to open A. But the song is in the key of E. Correct?

Yes.

How do you achieve the bassy octave riff that kicks off the tune live?

That’s the low-octave setting on the Whammy.

I love hearing the crowd hum along with that song on Under Great White Northern Lights. It may be the most identifiable riff of the past decade. Do you remember writing it?

I was sound-checking at the Corner Hotel in Australia when that came out. I thought about it as a possible James Bond theme, actually. And then I thought, “That will never happen [laughs].”

How does it feel when you’re watching something like a Michigan/Ohio State game, and the marching band and the crowd join together on that riff?

That’s wild. It’s becoming a big soccer chant in Europe. The President of Italy chanted the riff to a crowd when they won the World Cup. That’s really folk music to me—when people don’t know where it came from. That’s the highest compliment.

There’s a moment during It Might Get Loud when Jimmy Page starts playing “Whole Lotta Love,” and you have the look of a giddy ten-year-old kid. What was that like?

It was incredible. My favorite part was when Jimmy, Edge, and I all played “In My Time of Dying” together. You saw three different attacks on the blues, and three different styles of playing slide guitar. It was insightful to see three generations of guitar players attacking the same song—which is actually an old folk song that Led Zeppelin covered. I learned so much from those moments.

So what does it feel like to play with Page?

The overwhelming feeling is that he’s connected to the blues. That’s what put a smile on my face. It made me feel good because I knew that, despite our differences in age and where we came from, we’re both traveling down the same path—the one that heads straight for the blues.

Are you going to make a solo record?

I don’t know. I guess eventually. I always let the music tell me what to do.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Guitar Player is the world’s most comprehensive, trusted and insightful guitar publication for passionate guitarists and active musicians of all ages. Guitar Player magazine is published 13 times a year in print and digital formats. The magazine was established in 1967 and is the world's oldest guitar magazine. When "Guitar Player Staff" is credited as the author, it's usually because more than one author on the team has created the story.

“I knew he was going to be somebody then. He had that star quality”: Ritchie Blackmore on his first meeting with Jimmy Page and early recording sessions with Jeff Beck

“He used to send me to my room to practice my vibrato.” His father is the late Irish blues guitar great Gary Moore. But Jack Moore is cutting his own path with a Les Paul in his hands