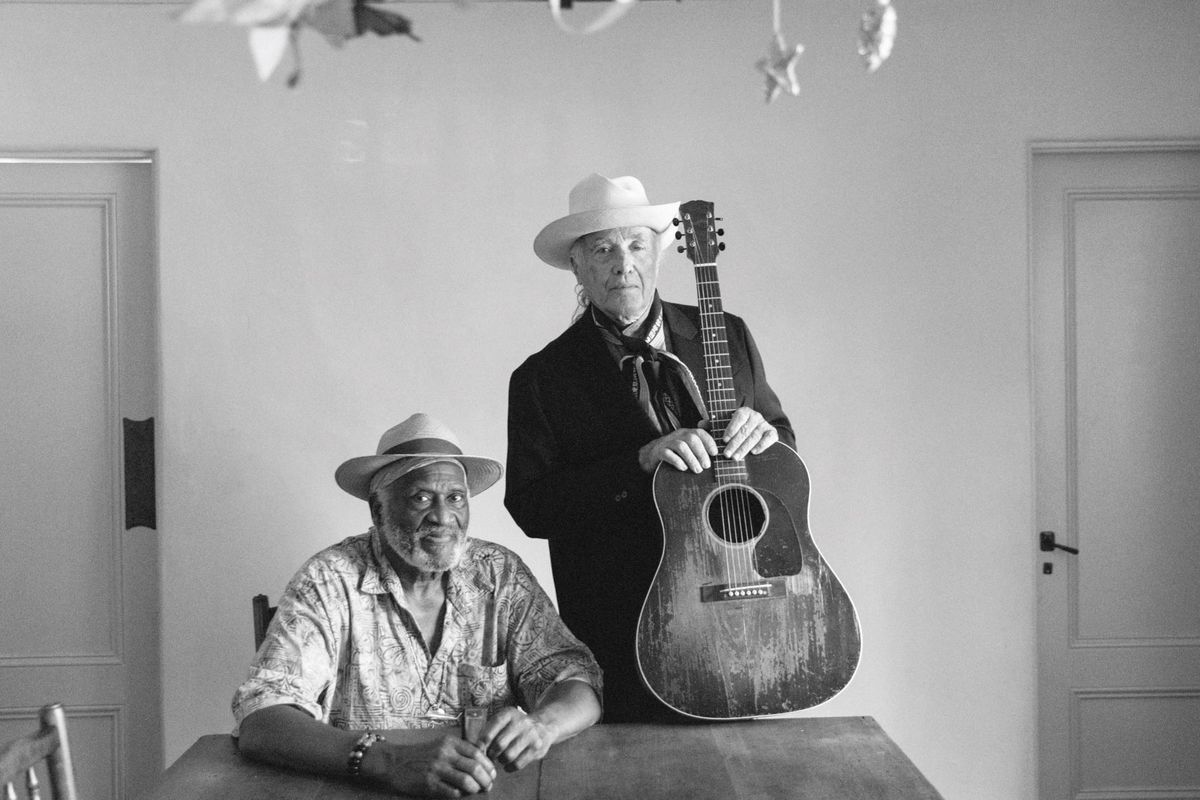

“It’s Okay to Sound Different from the Record”: Ry Cooder Reveals His Stage and Studio Secrets

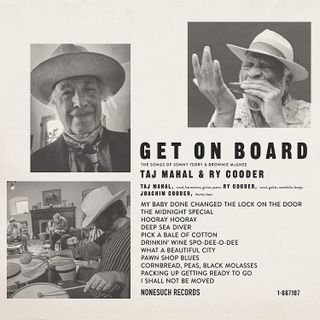

Discover the source of the authentic guitar tones heard on his new album with Taj Mahal, ‘Get On Board: The Songs of Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee.’

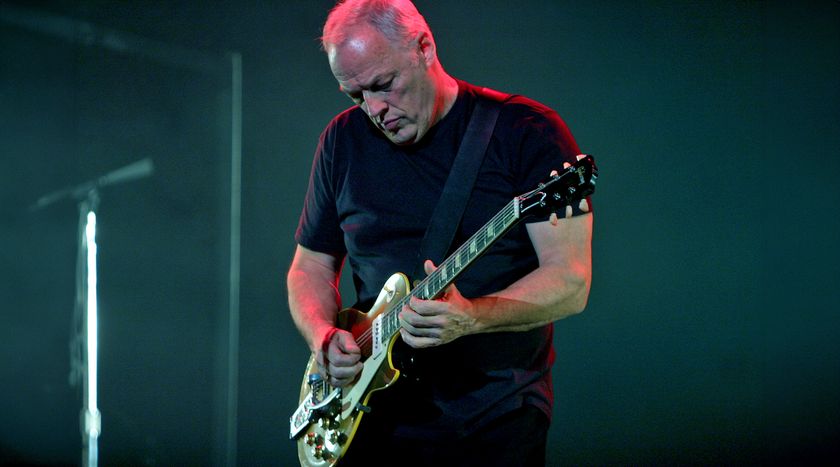

Last time, Ry Cooder began to take us along on the journey of how he and Taj Mahal got back in the saddle together after decades apart and recast themselves in the roles of folk-blues duo Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee.

Vocalist/harmonica player Terry and acoustic guitarist McGhee maintained a prolific partnership from the early ’40s to the mid ’70s, and Cooder and Mahal’s new album, Get On Board: The Songs of Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee (Nonesuch), is a nod to the songsmiths, who inspired them to join forces as the Rising Sons in 1965.

Today, Cooder and Mahal are Americana icons in their own right, intent on keeping the flame and passing the torch to those who may find new inspiration in the time-honored tunes and perhaps offer new interpretations for future generations.

Traditionals such as “Midnight Special” and “Pick a Bale of Cotton,” as well as the stylist elements that inform originals such as “Pawn Shop,” have been handed down through a century-long line of known and unknown troubadours using the six-string as a soapbox.

McGhee was a Piedmont blues stylist, and for these sessions Cooder adopted everything from his technique using vintage metal finger picks to his choice of acoustics, including his primary guitar, a 1946 Martin D-18.

As our conversation continues this month, the slide icon offers plenty of insights into both his acoustic guitar and electric guitar work and choice of amplification.

How did Brownie McGhee’s backstory inform your arsenal of instruments?

The sweet sound on the album cut “Pawn Shop” is a Gibson “banner” guitar, a 1943 J-45 [featuring the slogan “Only a Gibson is Good Enough” in a golden banner on the headstock].

I got that and the Martin D-18 thinking, Someday I’m going to want to be Brownie McGhee. So I had them ready to go. I knew Brownie had recorded with his banner J-45 because I’d seen pictures of him.

The sweet sound on the album cut 'Pawn Shop' is a Gibson 'banner' guitar, a 1943 J-45

Ry Cooder

He had tried to be an R&B guy for a while, you know. He had a pickup in an electric, and it sounded terrible, but he did try to do that juke thing. It didn’t work out for him. He had to figure out that the audience had changed.

Then he and Sonny Terry aimed the act at a White audience, and gave up on the Black audience. They weren’t interested anyway, you see. Things had changed so radically at that point.

How did you cop the electric juke sound for the lead on the first track, “My Baby Done Changed the Lock on the Door”?

I had to put something in there. We basically cut the album live, including the vocals, but I overdubbed bits and pieces of other stuff, just to give it some juice, you know, fill it up a little bit.

That’s my much-modified Stratocaster that I use for bottleneck most of the time. People know what that is.

The Coodercaster?

Sure, that’s what people call it, and it’s a nice instrument. It’s always been useful, especially onstage, because you can really execute. It’s got a great neck and you can really get around on that thing.

Who knows why instruments sound good. Some do and some don’t

Ry Cooder

It’s no good in standard tuning – sounds terrible – but it really rings out in open tunings. Weird.

Who knows why instruments sound good. Some do and some don’t. They may look the same, but none of them are the same. That guitar just worked out. I’ve tried to do clones of it and never got there, but somehow that’s a good one.

How did you get that gritty howling tone?

Sometimes you get lucky. That’s a White amplifier. [Forrest White] worked for Leo Fender, and for some reason he had his own subsidiary amp brand within the Fender family for a few years back in the ’50s.

This amp is a little bigger than a Champ and a little smaller than a Deluxe, with a little bitty eight-inch speaker. But it makes a big sound on a microphone. Terrific.

When you crank it up, it’ll howl, like you say, but at a low volume, which is really hard to get. Most guitar amps don’t sound good in a recording situation where you don’t want to be so goddamn loud.

I used a couple of echo devices. I forget which ones. I’ll use anything that meshes with the track. Your overdubs have to coincide. They have to be contoured to fit and make sense sonically. I was in a hurry.

These days I don’t want to spend too much time messing around with sounds. I want to get it done before I get tired. I did all of the overdubs in a single day.

These days I don’t want to spend too much time messing around with sounds. I want to get it done before I get tired

Ry Cooder

Taj, Joachim [Cooder’s son, who plays drums and bass on the album] and I recorded the whole record in three days. We did each song in one or two takes: “Map it out, but don’t blow the groove. Don’t get tired of it. Stop what you’re doing, start up again, and record the goddamn thing.”

I’ll bet that’s how Brownie and Sonny did it. They wouldn’t have needed a bunch of takes. And in those days you’d save tape. [Folkways Records founder] Moe [Moses] Asch would come in with a couple of reels and say, “Don’t go beyond this, because we don’t have any more tape.”

How about tunings?

It’s mostly in standard, because Brownie was in standard. He played in [the key of] G sometimes, and in E most of the time. In our case, I would ask Taj if he had a key he that he liked for his voice or harmonica.

“Beautiful City” is in G – well, it’s on a big guitar so it’s tuned lower than G, but it’s in G position [standard tuning lowered down a step and a half yields the sound of an E chord when fingering an open G chord].

The guitar on “Beautiful City” is a weird, monstrous 1905 Adams Brothers acoustic that’s as big as a guitarrón with a short little neck. So you can only play it in the first position, but it has this huge, ridiculous sound that’s like having its own echo chamber.

I’ve never seen another one or heard of the Adams Brothers, so I assume it was a special order. It’s an amazing guitar but you have to tune it down like Lead Belly, so you can’t play it in a lot of keys. It’s only good in E and G, but it’s fantastic in those two. It really rings like a 12-string.

It was fun to try something different to give variety to the album. “Pawn Shop” is played in standard tuning. I never play bottleneck in standard tuning because it’s un-harmonic, but I broke my rule in this case because I didn’t want to retune the guitar and lose some chord positions.

I didn’t want to overthink it. “Drinkin’ Wine Spo-Dee-O-Dee” is in open D and played on a Harmony Sovereign from the ’30s.

There’s some fine slide on “Wine.” Do you use the same one on acoustic that you use on the Coodercaster?

Well, sure, I’ve only got one. It’s the same bottleneck slide I’ve been using for over 40 years, since the ’70s. You get to where you like something because it does what it does. Another slide with another surface like metal would be entirely different.

Something about the weight is very important. If it’s too light, it sounds terrible. If it’s too heavy, you can’t get around. Then you start banging into the guitar with the doggone thing. So the weight of mine is thick enough that you get a good drag on it, but not so much that it slows you down.

It’s the same bottleneck slide I’ve been using for over 40 years, since the ’70s

Ry Cooder

The mandolin in the “Hooray Hooray” studio video looks nice and old. Is that a Loar?

Oh, good lord, no, a Loar? I’ve never made that kind of money. Are you kidding, six figures? Mine is a 1919 [Gibson] F4. It’s pre-Loar. It’s not pricey; I think I paid $600 for it in the ’60s. You couldn’t get near it for that today, it’s a nice instrument, but it’s not a Loar.

That F4 is very loud, which makes it good for playing rhythm and blues. When Taj and I were sitting there, I said, “Hey, didn’t I play mandolin on your first record?” He said, “Yeah,” and I said, “Well, this is the same one.”

In a recent feature, Lloyd Baggs [of LR Baggs] mentioned that he got his start in acoustic amplification working with you. He said that you had a rig the size of a refrigerator, and that the whole quest was to achieve a more realistic sound while reducing the rig to, say, at least the size of a microwave. Where are you at in that evolutionary process?

It’s very simple: I gave up trying to do that. It’s a losing battle. The problem has never been solved, as far as I know.

Now, one thing I’ve got here [at home] in this ’20s Stella is a little Seymour Duncan pickup. It’s not so big as to cover up bass frequencies, and it’s got two little controls: one for volume and one for EQ. That’s good because you can roll off the low end.

That sounds like the Active Mag. Does that seem right?

I think so. It’s great on this Stella 12-string, because it’s got enough high end. But of course the real deal is to have a good microphone, like a Neumann. Then you can jack that up and just flavor the sound in the mix at the place you’re playing with the pickup.

The trick is to get enough midrange so that you don’t play too hard

Ry Cooder

The trick is to get enough midrange so that you don’t play too hard, because that’s the problem. If the pickup is magnetic like an electric guitar pickup, then you’ve got too much midrange and not enough top. It sounds tubby.

The exception was Paul Bigsby, who had secret shit. He built some magnetic guitar pickups that are completely unique. Paul was such an exceptional guy, and he had a good design. He had good wire that he made out of an aluminum alloy used on aircraft carriers that he got from Lockheed Martin, because he worked there during World War II.

There’s not as much top end as you might like in that 16k range, but they sound amazing whether they’re on a solid-body electric or an acoustic. I’ve got a couple of those. They’re nearly impossible to get now, unless you spend the Earth.

I gave up going onstage with acoustics. Now, when we were on tour with Ricky Skaggs and the Whites a few years ago, I wanted to play my D-18, but I had to have some amplification. So I put the Bigsby pickup on there and ran it through a Magnatone amp that didn’t color the sound too much, like a Fender.

That provided some size so that it sounded good onstage, and then the engineer could mic it up without having to do a lot of re-equalization, which is the death of the thing.

You don’t use piezo pickups at all?

Oh, good Lord, no, I hate those things. That’s awful. And I’ve tried everything, believe me. That refrigerator setup I had was no good. It was heavy and impossible to control. It was a bad idea, just the wrong road entirely.

You can’t say, ‘I’m going to reproduce the living-room sound we got on the album on the stage,’ because it can’t be done

Ry Cooder

But now me and Taj are going to do some shows together, so I had to ask myself, What the hell am I going to play? You can’t say, “I’m going to reproduce the living-room sound we got on the album on the stage,” because it can’t be done.

What you need onstage is totally different. You have to reconfigure, so I started playing archtops with good old DeArmond microphonic pickups in them. That’s a great sound if you have the right one and the right amps, which I think I do.

I’m 75 today. You’d think I’d know something. You have to scale everything to the music, so figure out what makes the music sound right.

It’s okay to sound different from the record. This will be more of a juke joint effect, like at a barbeque, which is good because the audience needs to toe-tap and get happy.

We need to make sure we put that out there.

Order Get On Board here.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Jimmy Leslie has been Frets editor since 2016. See many Guitar Player- and Frets-related videos on his YouTube channel, and learn about his acoustic/electric rock group at spirithustler.com.

"Shredding is like talking a foreign language at 10 times the speed of sound. You can't remember anything." Don Felder reveals the unlikely influence behind his iconic guitar solo for the Eagles' “One of These Nights”

"Old-school guitar players can play beautiful solos. But sometimes they’re not so innovative with the actual sound.” Steven Wilson redefines the modern guitar solo on 'The Overview' by putting tone first