“I’m Sick of All of the Existential, Post-Apocalyptic Doom”: Rick Holmstrom Reacts to the Current Crazy with ‘Get It!’

With a joyful noise this rapid release is all about having a good time.

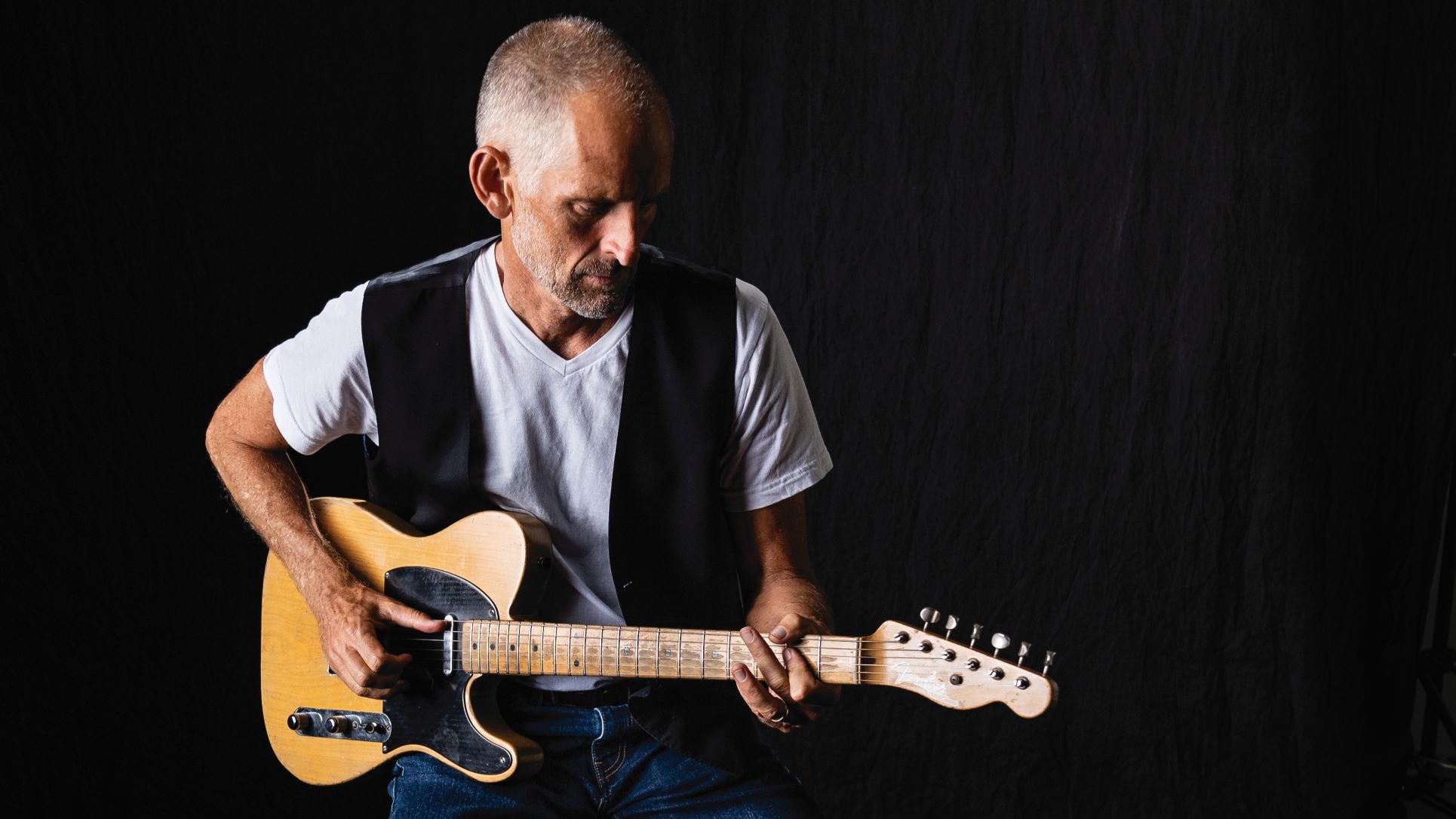

On his 2021 release, See That Light, L.A. blues legend and Mavis Staples guitarist Rick Holmstrom began to address the insanity of the current climate.

“Everybody’s staring at a screen, but we can’t see what’s in front of us,” he writes in one lyric. But on January 6 of that year, while waiting for See That Light to come out, the world became exponentially crazier.

“The news was driving me batty, so I started getting together with the guys, just playing and recording,” Holmstrom says.

“We were looking ahead to when we could get back together, have barbecues and listen to music. We were not thinking about anything other than entertaining ourselves and then being thrilled when we heard the playback. With the other record not yet released, it was nuts to be doing this, but it felt so good.”

Holmstrom, along with Staples’ bandmates Steve Mugalian on drums and Gregory Boaz on bass, found themselves quickly churning out Get It! (LuEllie Records), a record of short guitar instrumentals that hark back to the heyday of the Meters and Freddie King.

For this rapid release, the guitarist favored a small tube amp. “I used my Valco-made Bronson with one 10-inch field-coil speaker, two 6V6 power tubes and octal preamp tubes,” the guitarist says.

It was recorded with a Shure SM57 up close and a condenser mic a few feet away from the amp

Rick Holmstrom

“It is the Valco equivalent of a tweed Fender Harvard. I used it with a reverb tank and an SIB Electronics Echodrive delay pedal set for just a hint of slapback. It was recorded with a Shure SM57 up close and a condenser mic a few feet away from the amp. When you hear tremolo, it is a tweed Fender Tremolux.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“I like amps that have the bias tremolo. You can set the depth to a sweet spot, where you can hear it but it’s not such a choppy, on/off sound. It’s a little greasier and more organic.”

Most of the tracks were recorded in Mugalian’s garage on a Zoom multitrack recorder.

“I mixed the record at Pacifica, a low-budget studio where I did many of my earlier blues albums,” he recalls.

We did a lot of re-amping. We would put the whole drum kit through a guitar amp, and do the same thing to the guitar

Rick Holmstrom

“We did a lot of re-amping. We would put the whole drum kit through a guitar amp, and do the same thing to the guitar. We took the recorded Shure SM57 mic track from the Valco and ran it back through a Fender Tremolux or Vibrolux, just barely on, with two stereo condenser mics placed six or seven feet away from the amp.

"We would just put a taste of that track into the mix to add a bit more air, because the garage sounded kind of claustrophobic.”

Air is a crucial part of Holmstrom’s sound.

Though initially not a fan of the trio format, he eventually became fond of the intimate thing that happens when three people perform together.

“You throw a fourth person in and it changes everything,” he says.

You throw a fourth person in and it changes everything

Rick Holmstrom

Many guitarists, recording or playing in a trio scenario, would attempt to fill the space with distortion, flurries of notes or overdubs.

But while he’s adept at a style that lets him often play rhythm and lead simultaneously, Holmstrom is also unafraid of space.

“My friend and mentor Junior Watson came to see one of my first trio gigs in Long Beach,” he relates. “He said, ‘Man, the way you used space was great. You just hit a chord and let it ring out.’ I think it sounded good to do that because the room was so lively. I started doing it more often.”

The guitar on most of the record is Holmstrom’s 1953 Fender Telecaster that he has dubbed the Mariachi, but some of the dirtier tunes, like “Pour One Out” and “King Freddie,” feature his 1955 Gibson Les Paul Special.

It sports a push/pull pot on the bridge pickup tone knob that throws the two pickups out of phase for that vintage blues guitar honk.

It’s got all kinds of stuff wrong with it, which scared away the collectors. That’s the only reason I could afford to buy it

Rick Holmstrom

“It’s a TV model that has been refinished,” he explains. “It’s got all kinds of stuff wrong with it, which scared away the collectors. That’s the only reason I could afford to buy it.”

The track “G for Junior” references Watson, a master of the West Coast swing shuffle. Holmstrom demonstrates that the pupil has learned well, while making the style his own. Here, he exhibits a grittier Telecaster tone, turning the amp up and driving it with the tube preamp of the SIB.

Though it may appear that he is playing exclusively with his fingers, the guitarist actually has a pick clutched between his first and second digits at all times.

“It started when I was playing with William Clark,” he explains. “Guys like Smokey Wilson, Philip Walker and others would come down after work, wearing their mechanics uniforms. Sometimes they would get up and play with us. I saw that none of them had picks.

most of what I was hearing from these old guys was the flesh of their fingers. I started trying to do that more, but I wouldn’t put the pick down

Rick Holmstrom

“Maybe someone like Jimmy Rogers would have a thumb pick and some other pick on his finger, but most of what I was hearing from these old guys was the flesh of their fingers. I started trying to do that more, but I wouldn’t put the pick down.

“It somehow just migrated into my fingers; I didn’t even think about it. I sometimes use it when I’m playing rhythm or when I need to be cleaner, louder or faster.”

Another Holmstrom trademark is how his body motion seems so integrated into his playing. According to him, it’s connected to his listening process, and his first concern: rhythm. “That’s something I’ve been doing ever since I started playing,” he says.

“It’s like I’m off somewhere else listening to the groove of the whole group, and I’m definitely very rhythm conscious.

I’ve been working with a metronome for many years

Rick Holmstrom

“I’ve been working with a metronome for many years, because a drummer I was playing with when I was younger told me, ‘You need to get a metronome, set it on two and four and make the music swing like crazy, or you’re wasting your time.’ I’m trying to do that.”

For Holmstrom, one advantage of lockdown was the opportunity to dive deep into the details and nuances of his guitar playing. A record he has been studying is Little Milton’s Chess album Sings Big Blues, which features chestnuts like “Sweet Sixteen” and the Milton classic “Feel so Bad.”

“Junior Watson told me in the late ’80s to get that record and practice along with it,” Holmstrom says. “I put it on a year or two ago, when all this started. I’d forgotten how much stuff I’d picked up from Milton. But there are some things I had learned wrong. Like, sometimes it’s not the flat seven but the sixth, bent up.”

He also began to examine the pick-up notes leading to the downbeat.

I went back to Freddie King and all these other people I was into in my early 20s and realized it’s the feel of the pick-up notes that makes it

Rick Holmstrom

“I started to hear that on the Little Milton record,” he explains. “Then I went back to Freddie King and all these other people I was into in my early 20s and realized it’s the feel of the pick-up notes that makes it.”

For years, Holmstrom has been known as a blues master, and rightly so, but he is much more. Even at his “bluesiest,” he separates himself from many of the genre’s current generation by eschewing any hint of a Stevie Ray Vaughan influence, or cranking up the distortion to blues-rock levels.

Instead he exhibits excellence in lesser-exposed styles, like West Coast swing, Slim Harpo funk and Lightnin’ Hopkins’ down-and-dirty one-man band approach.

On the other end of the spectrum, he has pushed the tradition’s envelope by adding hip-hop production techniques to his 2007 release, Hydraulic Groove.

All of the above has been absorbed into a personal approach and sound that is instantly recognizable.

In more recent times, Holmstrom has added a deep knowledge and feel for gospel to his arsenal, with more songs reflecting the gentle, almost country lope of some of the early church styles.

“For many years, Mavis and her sister Yvonne would sit behind us while our band did a little instrumental section,” Holmstrom says. “I used to play the gospel tune ‘Oh, Mary Don’t, You Weep.’ I was knocked out by the Swan Silvertones’ version.

“Sometimes, I might not know what I felt like doing and would look over at Mavis for inspiration. She’d go, ‘You know what I want.’ ‘Oh Mary’ is a gospel feel with brushes or light sticks and a lot of air.”

The final song on Get It! – “Walking With Diane” – reflects this aspect of the guitarist’s playing.

“That song is about my mom, and I was trying to write something that would convey the feeling of thinking about her,” he says.

“I don’t know what you call the style. I just try to think of melodies and ways to play simple groove stuff without words. Most of this record is about fun. I’m sick of all of the existential, post-apocalyptic doom. I just want to have a funky good time. That’s all this record is.”

Order Get It! by Rick Holmstrom here.