“I’m Not Really so Impressed by the Guitar Playing; I’m More Interested in Hearing People Talking to Each Other on Their Instruments”: Rising Star Jakob Bro Talks Finding His Voice and the Mystery of Music

With his guitar, looper and effects, the Danish sonic explorer captures moods in dreamy improvisations

Through the course of five evocative ECM albums, Danish guitarist Jakob Bro has forged a distinctive musical identity with a deft fingerstyle approach to his instrument, along with a penchant for delicate lyricism and intuitive flights that often take him into the unknown.

Making subtle use of looping technology, backward effects and the occasional onslaught of distortion has allowed him to go from soothing introspection to translucent soundscapes to angular skronking, sometimes within the same piece.

The 44-year-old sonic explorer made his ECM debut on drummer Paul Motian’s 2006 album Garden of Eden, which featured the three guitars of Ben Monder, Steve Cardenas and Bro blending brilliantly in the mix.

It was really a big step when I went from doing my own records on my own label [Loveland Records] to recording for Manfred Eicher on ECM

Jakob Bro

He appeared three years later on Polish trumpeter Tomasz Stanko’s darkly introspective 2009 outing on ECM, Dark Eyes, then debuted as a leader on ECM in 2015 with Gefion, featuring bassist Thomas Morgan, a frequent collaborator of Bill Frisell’s, and veteran Norwegian drummer Jon Christensen, a member of Keith Jarrett’s celebrated European Quartet of the 1970s.

“It was really a big step when I went from doing my own records on my own label [Loveland Records] to recording for Manfred Eicher on ECM,” Bro says. “I wasn’t even sure I wanted to present a guitar trio on my first album with him, but he really helped me by stepping up and saying, ‘You have a voice on the instrument.’”

Bro followed with three intimate offerings on ECM – 2016’s Streams, 2018’s Returnings and 2018’s live trio recording, Bay of Rainbows – all showcasing the guitarist’s warm, inviting tone, tastefully fluid improvisations and engaging melodicism, mixed with a decidedly mysterioso quality.

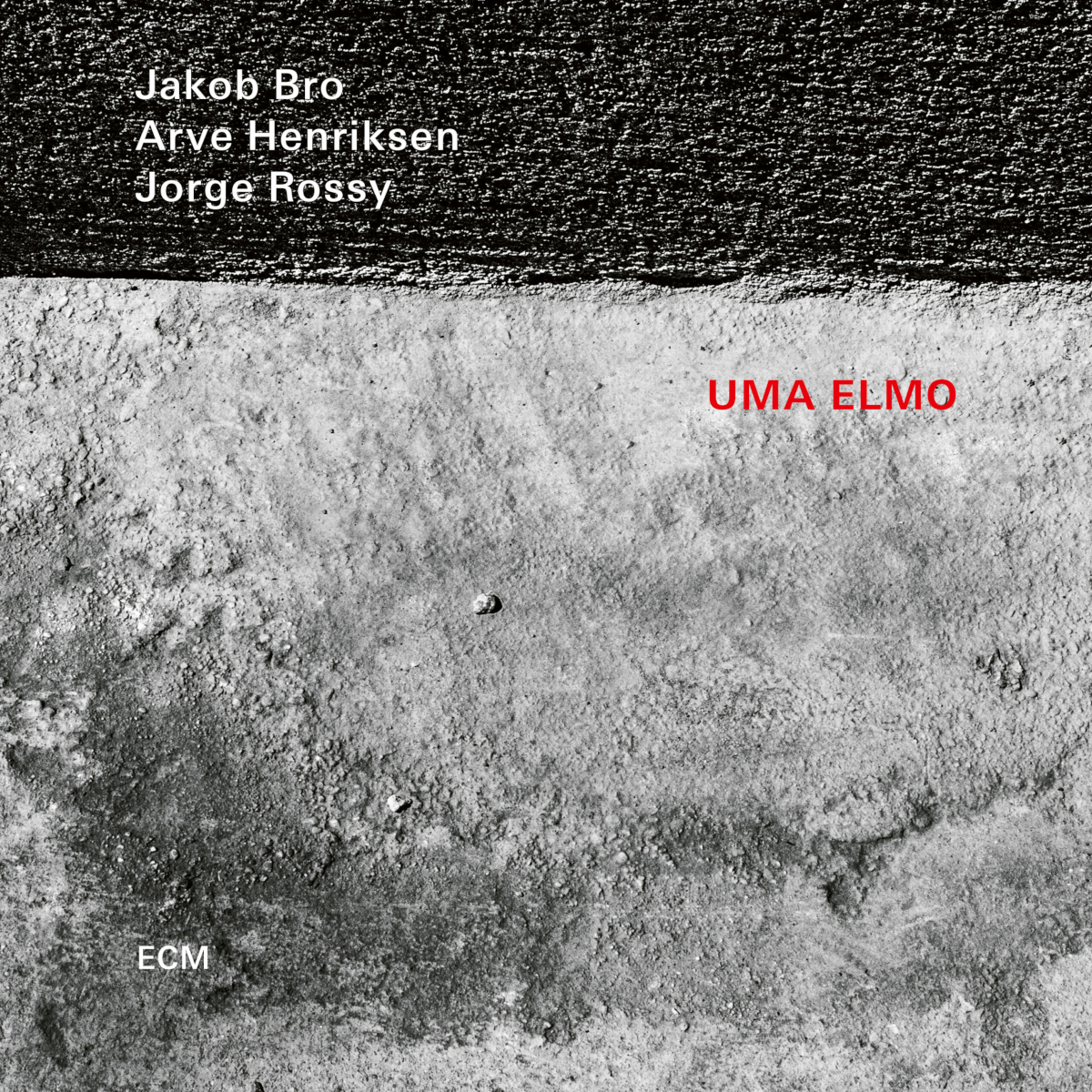

2021’s Uma Elmo was recorded during the pandemic in two days at a Lugano, Switzerland studio, with an international crew of Norwegian trumpeter Arve Henriksen, Spanish drummer Jorge Rossy, producer Eicher and Italian engineer Stefano Amerio.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Named for his two small children, three-year-old Dagny Uma and seven-month old Osvald Elmo, Uma Elmo is a remarkably expressive and highly personal statement by the accomplished guitarist and features tributes to two of his late mentors: the legendary alto saxophonist Lee Konitz (“Music for Black Pigeons”) and Stanko (the minor-key lament “To Stanko”).

Bro’s dreamy, translucent and eminently open music is the result of him trying to capture moods through his guitar and textural looping techniques, done in real time rather than overdubbed. As he explained, “My compositions are about catching a glimpse of a feeling, sketching it down and then unfolding these sketches and letting them take you places you haven’t been before.”

My compositions are about catching a glimpse of a feeling, sketching it down and then unfolding these sketches

Jakob Bro

The rising star has a pair of new albums on ECM. Once Around the Room: A Tribute to Paul Motian is an all-star homage to the late drummer-composer and Bro’s former beloved employer. It’s a septet outing co-led by tenor sax great Joe Lovano and featuring double bassists Larry Grenadier and Thomas Morgan, guitarist-bassist Anders Christensen, and drummers Rossy and Joey Baron.

Bro is also releasing Live at the Village Vanguard with his own quartet, which includes drummer Andrew Cyrille, tenor saxophonist Mark Turner and bassist Morgan.

In addition, Bro and his music were the subject of Music for Black Pigeons, a 90-minute documentary by filmmakers Jørgen Leth and Andreas Koefoed that premiered at the Venice Film Festival in September 2022.

It features interviews and performance footage with several of his colleagues, including Lovano, Motian, Stanko, Morgan, Grenadier, Frisell, Konitz, Eicher, Jon Christensen, Midori Takada, Palle Mikkelborg and Cyrille Turner.

The guitarist conducted this Skype interview from his home in Copenhagen...

How did you cope during the pandemic? Did you do any remote teaching or live streaming concerts?

No, nothing. I was playing with my band at the Village Vanguard in New York in February [2020], and then things shut down. I had maybe 80, 90 concerts canceled after that. The only thing that didn’t get canceled was this album on ECM [Uma Elmo].

And for a while it just seemed like it was not going to happen because we were in the midst of a global pandemic and everyone was in lockdown in a different country. But there was a gap of two weeks where things actually were possible, and so we made that record.

I wrote all the music during the pandemic. Instead of going on the road, I had time at home to write and be with my wife and children. And then the cancellations just kept coming. So, basically, I had all the time in the world to work on the music for this record.

When Paul [Motian] invited me into his group, I was really young. To me, it was the same as if Johann Sebastian Bach would have reached out to me

Jakob Bro

I composed most of the material for the recording in between Osvald’s naps when he was a newborn.

I remember seeing you at the Vanguard in 2004 or so with Paul Motian’s Electric Bebop Band, just before you recorded Garden of Eden. I didn’t know who you were at the time, and my first thought was, Three guitars? Is Paul crazy?

Yeah, he was crazy, and that was my good luck. I did a three-week European tour with him in 2003, and at some point after that he decided that he didn’t want to travel anymore; he wanted to just play in New York. And he invited me over for that week at the Vanguard.

When Paul invited me into his group, I was really young. To me, it was the same as if Johann Sebastian Bach would have reached out to me. He’s that big for me. And I learned a lot from just hanging out with him.

I think one of the main things that I got from Paul is an appreciation for the sort of mystery about music. Why is some music really affecting me? Why is some music moving me? Why is something stronger to me than other things? That’s a mystery somehow to me still.

And playing with Paul, playing with Tomasz Stanko or Lee Konitz, all of the older generation musicians put an emphasis on the fact that music is still a mystery. Lee will pick up the horn and play one note and I get goosebumps. The same with Paul when he hits a cymbal or Tomasz when he plays a single note on the trumpet.

All those people have reached a point with their music where it went further than just being the instrument. It’s almost like it’s their life coming out of the sound they create, which is fascinating to me, and also inspiring. And it triggers me in a way, because I don’t know how to do that. It’s something completely abstract to me.

But just being surrounded by that thing, it’s really strong. That’s probably the most valuable thing for me, in terms of having played with musicians from the older generation. Having Paul Motian wash you with his cymbal every night at the Village Vanguard for four weeks total is an experience that is so valuable to me that it will always be a part of me somehow.

And I like to think that it’s also something that will come out in my music, in some way.

I really started getting into being fascinated by standard material by listening to Kurt Rosenwinkel, Brad Mehldau’s trio and, of course, Paul Motian’s band

Jakob Bro

You went to the Berklee College of Music in Boston, where I imagine you encountered a lot of bebop and standard jazz repertoire while transcribing tons of solos. And it seems like you’ve evolved away from all that in your own music.

Yeah, before Berklee I went to the Royal Danish Academy of Music in Copenhagen when I was 17 years old. I was there for one year, and during that year we had a seminar with [saxophonist] Michael Brecker, [pianist] Danilo Pérez, John Abercrombie and [bassist] Eddie Gómez.

That seminar was kind of a turning point for me. Michael Brecker and Danilo and Abercrombie came up to me after the student concert; they sort of cornered me, and I was completely freaked out. And they were like, “You have to come to the U.S. to study.” So that was my reason for quitting the Royal Academy of Music in Denmark.

That same summer I met Kurt Rosenwinkel here in Denmark. I was playing a concert with a trio, and we were playing a John Coltrane song called “26-2,” and all of a sudden this guy comes up and asks if he can play a solo in the middle of the song. And I was like, What the fuck!

But I give him my guitar and he plays a great solo, then gives me the guitar back and we finish the set. And I go up to him afterward and he says, “Thank you for the music. My name is Kurt Rosenwinkel. If you ever come to the U.S., look me up. I want to hang out with you.”

So those two incidents that summer sort of made me want to quit my studies in Denmark and go to the states to study at Berklee. I was there for six months, not doing much, just practicing all the time. It wasn’t until I came to New York a year later that I really started getting into being fascinated by standard material by listening to Kurt Rosenwinkel, Brad Mehldau’s trio and, of course, Paul Motian’s band.

How were you able to find your own voice on the instrument?

I think the real turning point was being in Paul Motian’s Electric Bebop Band. Being surrounded by all these great musicians – Tony Malaby, Steve Cardenas, Jerome Harris, Chris Cheek, of course Paul himself – was so inspiring.

I think the real turning point was being in Paul Motian’s Electric Bebop Band

Jakob Bro

And then playing Paul’s original material night after night had such a strong and deep impact on me that I just started composing at that time. That’s when I feel like I started making sense as a composer. And I can see now that the first things I was writing after joining Paul’s band were very similar to Paul’s way of using breaks for the drums and using his arrangements.

Then, somehow, I feel like I found a way that was sort of more in line with where I come from. I’m not from the U.S.; I’m not from New York. I’m from a tiny place near the beach in Denmark [Risskov]. And I feel like, slowly, my compositions started reflecting some of that as well. So it’s been a journey for me, having my sound as an instrumentalist develop, having my compositions develop, finding how much improvisation do you want, how much composed material do you need to make this music come alive somehow.

And Paul Motian was a really big inspiration for all of that coming together.

Isn’t the very atmospheric opening track on Uma Elmo, “Reconstructing a Dream,” one that you played in Paul Motian’s band?

We played it on gigs and we recorded it, though it never came out. And “Slaraffenland,” which is on the album too, is another we played with the Electric Bebop Band. Paul would use it as an encore here and there when we were playing in Europe.

And for me, it was like a dream come true to hear him play my music. He was so kind to me and really supportive in that way.

When you speak of Motian and the influence that he had on you, that necessarily brings to mind Bill Frisell, who played with him so frequently in Motian’s trio with saxophonist Joe Lovano. Was Bill’s approach to the guitar a direct influence on you?

I love Bill. I’ve always loved him, mostly with Paul Motian. For me, that’s some of the greatest music of all time. I can stay with Paul Motian’s On Broadway volumes I and II for my whole life, basically. That’s enough info right there.

I love Bill [Frisell]. I’ve always loved him, mostly with Paul Motian. For me, that’s some of the greatest music of all time

Jakob Bro

When I started out playing guitar – I actually started out on trumpet before I switched to guitar – I was listening to Bill, Pat Metheny, John Scofield, John Abercrombie, Mike Stern, Ralph Towner, Jim Hall, Pat Martino. Those were my main influences in terms of jazz guitar.

But after a year or so I started regretting that I stopped playing the trumpet, because the music I was really loving at that time when I was learning jazz was Miles, Coltrane, Monk, Billie Holiday, Bill Evans. I was fascinated with the older generation and the more acoustic-sounding music. I was so fascinated by Sonny Rollins for a long time, and I was also transcribing all of Lester Young’s solos.

The trumpet players for me have always been Miles, Stanko, Tom Harrell. And my all-time favorite is Louis Armstrong. My dad’s hero was Louis Armstrong, so that was playing every day at home when I was growing up.

And I’ve gone through phases where I wished I played the trumpet or saxophone, because the guitar was hard for me somehow. It has been a struggle to find a way where the guitar would not be in the way of what I was hearing. That took me a long time, actually. Now I see the guitar as an essence. And while I have many heroes on guitar, I’ve never transcribed a Bill Frisell solo or a Pat Metheny solo.

That said, it’s incredible to hear Bill with Paul, especially the way he accompanies, like on On Broadway volumes I and II. It reminds me of the way Thelonious Monk accompanies, where they can create a whole world. You don’t even think of what chord Bill’s making; it’s just like a sound, basically.

Jim Hall could do the same thing. For me, those two are probably the most fantastic guitar players in terms of accompanying other musicians. I was listening today to the Paul Motian Trio’s It Should’ve Happened a Long Time Ago, and the way Bill is comping and the whole universe of sound he gets… I still have no idea how he’s doing it, but it’s completely fascinating to me.

Also, when you hear him in the different stages of his career, you can hear the whole history of guitar effects in Bill’s playing. And the way he’s using them is always so musical.

Frisell pioneered the creative use of looping devices, which is something you utilize in subtle ways throughout Uma Elmo.

I’m always inspired by Bill [Frisell], but I’m also inspired by electronic music. I’ve been listening to Aphex Twin a lot lately

Jakob Bro

Yeah, and it’s funny, because he’s still using that old green Line 6 looping pedal [the DL4 Delay Modeler], which is, like, ancient now in terms of what has been produced since then. But it’s perfect for him, and he can do magical stuff with it. And it’s so different from what I’m doing, not because I don’t want to do it, but simply because I have no idea how he’s doing it.

But definitely, the whole thing about adding layers and textures to the music, and having things underneath, that’s been a thing that I’ve been inspired by and that I’ve wanted to do for a long time.

And, of course, Frisell is the grand master of all that. So I’m always inspired by Bill, but I’m also inspired by electronic music. I’ve been listening to Aphex Twin a lot lately. So the inspiration is coming from various sources.

What kind of looping pedals do you have?

It’s by an American company called Chase Bliss. I have their Tonal Recall and Blooper pedals and also an analog Red Panda Particle Granular Delay V2, which is a pedal that has a life of its own. My other effects pedals are a Zvex Ringtone sequenced ring modulator, a Gamechanger Audio Plus sustain pedal, and an Eventide H9 harmonizer, which is like a Swiss Army knife of effects. It has thousands of things you can do, but I have narrowed it down to 10 or 12 sounds that I like to use. I also have a Klon Centaur Overdrive and a Neunaber Immerse Reverberator.

My fascination with effects started when I was playing with Tomasz Stanko’s quintet. That setup was so traditional – drums, bass, piano and trumpet – and I thought the guitar was like an alien in that setting. But Stanko was encouraging me always to find my own spot in that music, so I started experimenting with effects pedals.

A clean sound was cool in some settings – when playing a ballad or something – but sometimes the energy of the band was really high and I needed something where I could just step right in there and do something with my instrument, where everybody wouldn’t have to lower their energy. And for that reason, I just started experimenting with effects.

[Tomasz] Stanko was encouraging me always to find my own spot in that music, so I started experimenting with effects pedals

Jakob Bro

I had a Tube Screamer, an old Boss looper, a Zvex Ringtone modulator, a reverb pedal, a delay pedal. And Stanko really just encouraged me to go off. So during my time in his band, I really went in different places. Sometimes I was afraid that it was too much, but he was always super cool about that, actually.

You are part of a lineage of guitarists trying to sound like saxophone players in their long legato lines.

Yes, there was a time when I wished I could play like Coltrane or Miles, Sonny Rollins, Lester Young. But one thing I’ve realized in my journey is that it’s not going to happen with this instrument. The way Coltrane is playing on the saxophone, the way George Garzone or Joe Lovano is playing on the saxophone – I’ve tried to convert that to my guitar, transcribing hundreds of solos, but I’ve never found a way to play like that on the instrument and make it fit into my overall vision of the music.

And I realized at some point that this instrument is doing other things. So I have to take the sort of expression from the people I love – the vibe, the atmosphere, the whole emotional part of it – and see if I can learn how to make that come out of my guitar. And that’s something that has changed my attitude.

There was a time when I started hating the guitar because I was frustrated with not being able to play those long saxophone lines. Now I sort of love it for this reason. Because I’m thinking that if I played the saxophone, it would have been much harder for me to have found a path of my own.

There would have been so many heroes of mine that I wanted to sort of follow, and that’s not really the case with the guitar. It’s more of a musical thing for me.

I understand you have a new guitar?

Yes, I have a pink Nash Telecaster. It’s made by a luthier named Bill Nash, who Bill Frisell introduced me to about six years ago. It’s not a fancy instrument, but it’s really well-made. I got rid of all my old guitars for touring. I don’t want to deal with stress at the airports and stuff like that. This is my guitar now. I only have one.

I used to play with a pick, and I was practicing like hell with a pick. And then two, three years ago, I just threw it out

Jakob Bro

Are you playing with fingers throughout Uma Elmo? Or are there some songs or passages where you are using a pick?

I used to play with a pick, and I was practicing like hell with a pick. And then two, three years ago, I just threw it out. I kept seeing myself putting the pick in weird places, and then it was sort of in the way. I just felt like using a pick was one step removed from my fingers touching the instrument. And now playing with fingers gives me a different sort of freedom, though I’m definitely limited now.

I mean, in terms of playing lines, I can’t play what I could with the pick. Like, if I transcribed Coltrane’s solo on “Countdown,” for instance, I wouldn’t be able to play that with my fingers right now. I could do it with a pick, but not with my fingers.

But in terms of my own music, I’ve always felt like I could do the things I heard with just my fingers.

Definitely. I remember recording that first record I did for ECM with Jon Christensen and Thomas Morgan. Listening back in the control room with Manfred Eicher, I remember thinking that I sounded too much like Frisell here or Pat Metheny there or John Abercrombie at times.

Would you say you have evolved in your playing since Gefion, your debut album in 2015?

I’ve never really listened to something and said, ‘Wow, that’s just virtuoso. I wish I could do that.’ I’ve always listened to the soul and the music around it

Jakob Bro

And at some point during the recording I just felt like I couldn’t play anything, because all those guys were in the room. I think I went almost a year where I couldn’t listen to the album because I was so ashamed of it. I was like, “I can’t put it out. I’m bending a note at one place where you can clearly hear that’s a Metheny thing or that’s a Frisell thing.”

And I was giving myself such a hard time about it, really. Now, I love those players. Frisell is an incredible human being, and he’s an incredible musician. The same with Pat Metheny. The way he’s playing the acoustic guitar on “Lonely Woman” from his Rejoicing album is just incredible.

But it’s just music to me. I’ve never really listened to something and said, “Wow, that’s just virtuoso. I wish I could do that.” I’ve always listened to the soul and the music around it. So I’m not really so impressed by the guitar playing; I’m more interested in hearing people talking to each other on their instruments. That’s when the music, for me, is happening.

Bill Milkowski's first piece for Guitar Player was a profile on fellow Milwaukee native Daryl Stuermer, which appeared in the September 1976 issue. Over the decades he contributed numerous pieces to GP while also freelancing for various other music magazines. Bill is the author of biographies on Jaco Pastorius, Pat Martino, Keith Richards and Michael Brecker. He received the Jazz Journalist Association's Lifetime Achievement Award in 2011 and was a 2015 recipient of the Montreal Jazz Festival's Bruce Lundvall Award presented to a non-musician who has made an impact on the world of jazz or contributed to its development through their work in the performing arts, the recording industry or the media.