“I’m feeling Like FrankenStern – Kind of Rewired and Half Bionic”: Mike Stern Reveals How He Perseveres One Gig At a Time

Five years after a misstep on a New York City street left him badly injured, the maestro promises, “I’m never going to give it up.”

While Mike Stern was very capable of delivering the kind of post-Hendrixian six-string assaults that Miles Davis was looking for in his eagerly awaited “comeback” band (with bassist Marcus Miller, saxophonist Bill Evans, percussionist Mino Cinelu and drummer Al Foster), the guitarist was also someone who loved the warmth, harmonic sophistication and sheer swing of Jim Hall, one of his preeminent role models.

Stern has successfully combined both aesthetics throughout his own career, which included appearances in Billy Cobham’s group, Jaco Pastorius’ group, Steve Smith’s Vital Information and Harvie Swartz’s Urban Earth before he finally released his 1986 Atlantic Records debut, Upside Downside.

He subsequently played with Steps Ahead, Vital Information, Michael Brecker, David Sanborn, Joe Henderson, the Brecker Brothers and the all-star Four Generations of Miles band.

To date, Stern has released 18 albums as a leader or co-leader, including collaborations with fellow guitar hero Eric Johnson (2014’s Electric) and keyboardist fusion pioneer Jeff Lorber (2019’s Eleven).

But Stern’s career was put in serious jeopardy on July 3, 2016, when he was hailing a cab in front of his Manhattan apartment and tripped over some concealed construction debris, fracturing both humerus bones in his arms. He required multiple surgeries to repair significant nerve damage in his right hand that prevented him from holding a guitar pick.

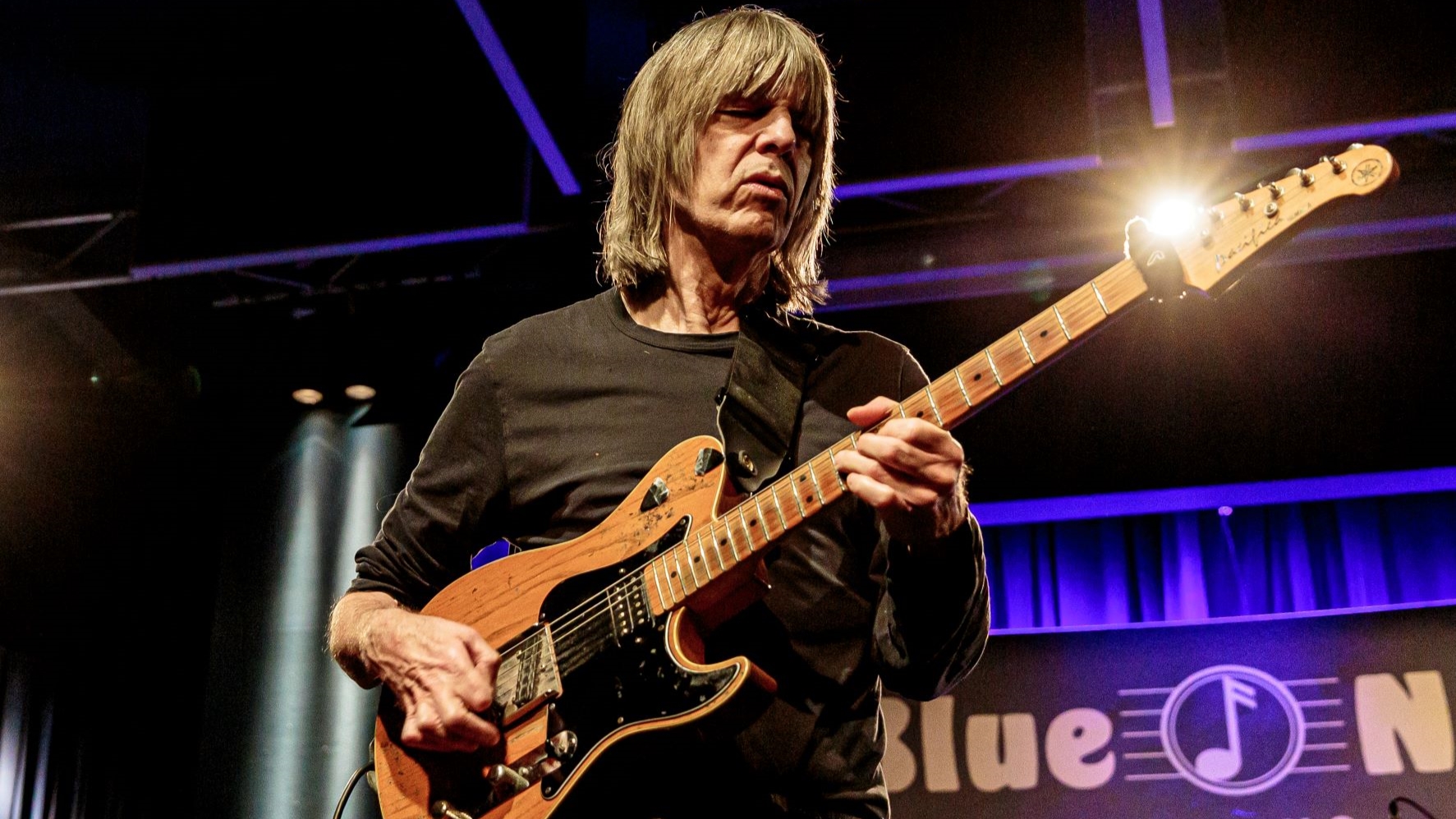

Stern emerged in late October that year to perform at the Blue Note nightclub in Manhattan with Chick Corea, playing seated and wearing a black glove outfitted with Velcro attached to a Velcro-fitted pick.

Following a second surgery, he gained more control of his nerve-damaged right hand by gluing and taping his fingers to a pick.

In January of 2017, six months after his accident, Stern began recording his next album, the ironically titled Trip. Some of the song titles on that comeback album including “Screws” and “Scotch Tape and Glue” were tongue-in-cheek references to his new procedure of having to “strap in and glue up” in order to hold a pick.

Despite the debilitating injuries, Stern’s signature speed and “chops of doom” are still very much in evidence on that 2017 album.

After persevering through Covid-19 and the complete lockdown of nightclubs in New York City from March 2020 to July 1, 2021, Stern is back playing every Monday and Wednesday night at his beloved 55 Bar (affectionately known as The Dump) in the West Village.

And after lengthy tenures with Atlantic Records, Heads Up and Concord, he is now preparing new material for an upcoming recording for Shanachie.

Meanwhile, the guitarist has a prominent role on Going For It, an archival recording by the Harvie S Trio featuring legendary drummer Alan Dawson.

Recorded at the 1369 club in 1985, it’s a classic example of Stern at the peak of his game, playing jazz guitar standards in an intimate club setting, just as he continues to do every Monday and Wednesday night at the 55 Bar in New York City.

You mentioned that you recently had another surgery that has improved matters for your right hand, in terms of holding the pick.

Yeah, it’s very rare to get permanent nerve damage from something like that accident I had, where I broke both bones in my shoulders. I’m lucky I got a great orthopedist, Dr. Alton Barron, a shoulder-elbow-hand specialist in New York City. He’s worked with a lot of musicians, including Elvis Costello and Bruce Springsteen. They had issues and he helped them out, and a whole bunch of classical musicians as well.

He got me playing right away, which was really difficult because he went very slowly, step by step. He wasn’t able to give me back too much right away, but gradually it got better and better. And now the fourth surgery on my hand helped a lot with my thumb. It’s just in a better position now.

The procedure is a weird tendon transfer, where they just kind of rewire you

Mike Stern

The procedure is a weird tendon transfer, where they just kind of rewire you. Apparently, you have extra tendons in your hand that are either redundant – where there’s two doing the job of one – or they sit around unemployed until such time as something like this happens.

So Dr. Barron was able to put me back together in a very satisfactory way, even though now I’m feeling like FrankenStern – kind of rewired and half bionic.

Did you have nerve damage in both hands?

No, thank god. The left hand is totally cool, so I can still do all that stuff on the fretboard. My right hand with the pick has been the problem, so I have to use glue to be able to hold the pick now. That hasn’t changed. Probably never will. I just can’t grip it in the same way.

There’s just not enough strength there, but it’s better. I still have to use the glue, but I don’t lean on it 100 percent. I’ve got some strength to really grip now.

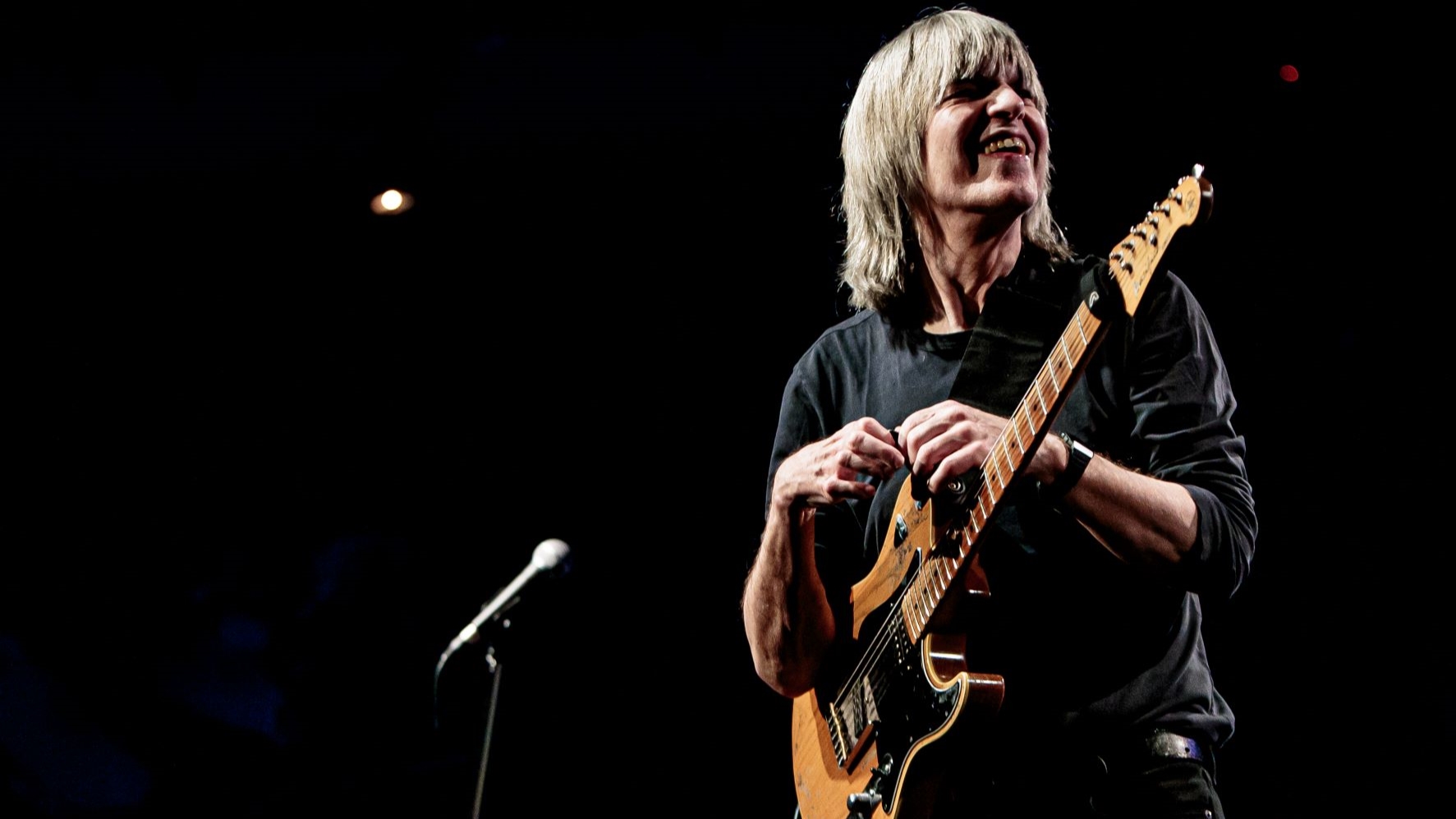

From listening to your last two records – Trip and Eleven – it’s hard to hear that you suffered any setbacks at all. You’re still killing it.

Yeah. This accident happened five years ago and over the past four years or so, no one’s even mentioned it. People hear me play and they say, “Wow, what injury?” Or if people know about it, they say, “I can’t tell the difference.”

I notice, of course. It’s a use of different muscles that feels different in certain things I play. And it’s hard. There’s stuff that I used to be able to do that I can’t do in the same exact way anymore. But the idea is you learn and you compensate. You figure out a way around it.

The one thing I used to do a little bit more is play with my fingers. I was more a pick guy, but sometimes I would put the pick in the palm of my hand and use my fingers for chording. And I can’t do that anymore. But there’s a way my doctor can fix that too, sometime down the road.

How soon after your first surgery did you begin playing again in public?

I went on a long tour about two months after the accident, and I continued playing on the road up until the pandemic. Sometimes if I had some time off, I would do another little surgery, and it helped matters.

Every time the doctor did something, it would help. He didn’t want to jump in and do everything all at once. I’m just glad I’m able to keep playing. I certainly wasn’t going to give this stuff up, and I’m never going to give it up, until I drop.

I’m never going to give it up, until I drop

Mike Stern

That’s interesting what you said about playing with fingers, because on that new Harvie S Trio live album, documenting that gig from 1985 at the 1369 Club in Boston, you’re playing beautiful chord melodies on Horace Silver’s “Peace” and on John Coltrane’s “Moment's Notice.” There’s a lot of fingerstyle playing on that record.

Yeah, there’s more of that going on. And some of that is with the pick also; it’s just lightly played. But it’s kind of a combination.

That record was just a really special night. I’ve done a ton of that kind of stuff over the years. Since the early ’80s I’ve been playing at the 55 Bar in New York, just stretching out over standards with different really great musicians that just want to play.

You know, no one’s getting rich at those little clubs, but it’s really fun to play there. You can do what you want, with no pressure. It just feels like those are the places where you can really find some new stuff.

Even if you play the same tunes, you kind of change them up a little bit and you end up finding new stuff on everything, whether it’s a blues or a ballad or just swinging on a standard.

This gig with Harvie S and Alan Dawson was a similar thing. And I had never played with Alan Dawson before. I certainly had known about him, and I might have met him once when I was going to school at Berklee.

He was the main percussion teacher there, the head of the drum department; an amazing player and an amazing teacher who also wrote some instructional books that are kind of like a Bible for drummers.

And so we hit it without a rehearsal. We had three nights there and someone had taped it on a reel-to-reel recorder. We weren’t in a studio situation or even a remote trailer for live recording, but it just came out really good.

And it documented a kind of thing that I’ve been doing for years – that little club gig that I never really recorded before. Just kind of caught in the act, so to speak. My chops were really 100 percent, and it was a good night just generally.

The rhythm section, man! Those guys just hooked up so well together.

And you really linked up with Alan Dawson, even though you say it was the first time you ever played together. There was a moment in “Like Someone in Love” where you both kick it into double time simultaneously. There’s some kind of telepathy going on there.

Alan is something else, man. There’s a video on YouTube of him and Sonny Rollins that is so swinging it’s ridiculous. It was really a pleasure to play with him. You know, he was sitting there in his suit and tie, and I turn on the distortion pedal occasionally, and he’d say, “Whichever way you wanna go.”

And when the rhythm section is that supportive, it really feels so inspiring that it’s effortless. So this record is just a really good example of an incredibly sensitive, supportive, strong rhythm section. It was really a nice hookup for the whole three nights. I just remember feeling so comfortable.

This record is just a really good example of an incredibly sensitive, supportive, strong rhythm section

Mike Stern

And Harvie, I had played with him a bunch at that point. He’s just such a solid, supportive bass player and also a very creative soloist. He’s done so much with so many different cats – Dexter Gordon, Sonny Stitt, Thad Jones, Jim Hall, Sheila Jordan. He’s been around forever, and he’s wonderful to play with.

And Harvie and Alan Dawson really hooked up well together. It’s very inspiring when that happens – all three of us at once. I love that trio setting, and I don’t go far away from it. When I play my own tunes with my band, I usually add a saxophone, so it’s really still a trio when it’s time for me to solo.

With a trio there’s a flexibility that doesn’t exist with anything else

Mike Stern

With a trio there’s a flexibility that doesn’t exist with anything else. And just playing standards is something I’ve done so much before.

On that Harvie S Trio album, we did one original of mine, “Bruze,” which I wrote a long time ago for Tiger Okoshi, the Japanese trumpeter [it was later recorded on the 1988 Bob Berg album, Cycles]. Everything else was standards. And those guys just amazingly do what they do, which is follow the music.

When you listen to this document from 35 years ago, is your guitar sound different from what it is now?

Things have changed some. I’m using a different guitar, for one thing. But in a basic way, I’ve always stuck with what works. I’ve always liked a very vocal kind of sound, but clear, where you can hear every note.

But I don’t want every note necessarily to be articulated in the same way. I like it to feel like the way we talk or the way we sing. When you talk, you don’t accent every syllable. So I like that in terms of how I try to play. You don’t hit every note the same way; you’ve got dynamics within each note of each phrase.

When you talk, you don’t accent every syllable. So I like that in terms of how I try to play

Mike Stern

I go for more of that flow. I’ve always had that, and I try to keep it. I always tell students, “If you use pedals, if you use a certain kind of a sound with the amp in terms of adding more treble or taking the treble off... Whatever works for you, try to get your heart out there. Because that’s what it’s about. Don’t get in the way of what you want to communicate.”

Do you remember what your setup might have been on those three nights in Boston back in 1985?

It’s similar to what I’m using now. I’m always using Boss pedals. I think I used a Boss DS-1 Distortion and a Boss DD-3 Digital Delay on that gig, and I used two amps for that stereo sound.

And I had this [Yamaha] SPX90 [multi-effects processor] that I really liked. It has a harmonizer patch, not a chorus, for a slightly different effect. And it’s balanced to be more or less 50-50 with the straight sound and the chorus effect, which adds a bit more body. It has that kind of flow where you don’t hear it in your face. And you can play in a small place and it still sounds kind of big because of that.

So I’ve always used that kind of setup, and it’s also worked in the much bigger festivals.

I’m always using Boss pedals

Mike Stern

You’ve always favored that slight touch of chorus.

Yeah, the very first chorus thing I had was called the Rotosound, which produced a Leslie kind of effect. It was a pedal I got from Nils Lofgren, who was a friend of mine in Washington, D.C., where I grew up. I was already very much into jazz, but I was also doing some rock gigs, some blues gigs.

Nils was well known in the Washington, D.C. area, and then later on he started playing with Bruce Springsteen. But he used to play this Rotosound pedal and I really liked that.

And I also liked when Hendrix played with a Leslie. When I hear Jimi Hendrix, he has that vocal kind of sound that I emulated, obviously to a more extreme level. But I grew up checking that stuff out, so I kind of kept that kind of vibe through the years.

When I hear Jimi Hendrix, he has that vocal kind of sound that I emulated, obviously to a more extreme level

Mike Stern

And, of course, I liked Pat Metheny's stereo sound when he first came out, and he had all that stuff to make his guitar more vocal [including a Lexicon PCM 60 reverb]. I used to hear Pat play in little places in Boston with Jaco and Bob Moses before they did Pat's first ECM record together, and I loved his sound.

And I always loved Jim Hall and Wes Montgomery for their legato sound. Wes did it with his thumb. He got a very vocal, round kind of sound.

For me, a lot of getting that legato sound has to do with the way that I pick. It’s not real loud, not really hard. It’s really light, because that’s the way I like to hear it – more like a horn player, in some ways – unless I need it to be stronger.

If I really want a stinging note, then I have the option of doing that. But fundamentally, I’m playing as smooth as possible, but not without dynamics. It’s more difficult to get that kind of roundness and warmth with a solidbody electric guitar.

I used to play a Gibson ES-175 through just one amp, but then I couldn’t crank it if I wanted to play the blues and rock a little bit. And rather than schlep a bunch of different guitars around to use different things on different tunes on the road – that’s really next to impossible, especially nowadays – I just had one guitar that kind of worked for every situation.

Originally, it was Roy Buchanan’s Telecaster, which I bought from Danny Gatton. That got stolen from me at gunpoint in Boston, and then somebody made a copy of that, which I used for years. I still have that guitar.

But then Yamaha wanted to make a Mike Stern signature model, so they took that copy of the Roy Buchanan guitar and made something similar and did a great job. I’ve been using that ever since. But it’s always been a Tele-style guitar for me. And I’m still going for that kind of a warmer sound that’s more vocal or horn-like.

In recent years, Pat has taken some of the treble off his guitar, so it’s very warm now. I don’t want to take that much treble off. I still like a little bit more of that just to give it some clarity. But I still want that roundness at the same time.

Are you still using Boss pedals?

Yeah, that’s basically what I’ve always used. I have two Boss DD-3 Digital Delay pedals [one on a short delay for reverb effects, the other on a longer delay]. And instead of a Boss DS-1, which is the distortion pedal I used to use, I’m using a Boss SD-1 Super Overdrive pedal now. The Boss pedals really work. And I have a chorus effect in the Yamaha SPX as well.

I’m using a Boss SD-1 Super Overdrive pedal now. The Boss pedals really work

Mike Stern

I had just been playing again with Miles for the second time. I had played with Jaco, then I went into rehab. I had to clean up because I was a mess. So I had just gotten clean and everything was really coming more into focus for me.

I was getting high from the music more so than before, when there was other stuff I was getting high from. There was still plenty of good stuff that kind of got through during those days, but it was less consistent.

And this gig with Harvie was a really special night, where everything was clicking with the whole band. I was in the process of recording that first record I did for Atlantic Records, Upside Downside, and I was beginning to play with Bob Berg in that band that we had for a long time, with Dennis Chambers on drums and Jeff Andrews and then later Lincoln Goines on bass. But we kept it together for a number of years, and that was really fun.

So at the time of this 1369 gig, had you already started playing at the 55 Bar?

Yeah, I’d been playing there even before I went into rehab. I was still playing with Miles when Jeff Andrews found the 55 Bar on Christopher Street. And I was still living above 55 Grand Street at the time.

There’s no correlation between those two places; one’s in the West Village, the other’s in SoHo. It just happened that the addresses of both places were 55.

My wife, Leni, and I moved above the 55 Grand Street when I first started playing with Miles in 1980. I played with him for about three years off and on and then joined Jaco’s group after that. And we were still living in that place above the club at 55 Grand Street. During the time I was playing with Miles, Jeff Andrews said, “There’s a guy who wants to start music at this bar that’s been around forever.”

It’s a really cool scene, and we’re really working hard to keep it happening. It looks like it survived the pandemic, so I guess we'll see what happens next there

Mike Stern

So we started playing there around 1984. We started off playing duo and then later on we got a really good drummer named Yves Gerard, who played with brushes and chopsticks because we were scared we were going to get kicked out for playing too loud.

So we started to play there with the drums, and when no one complained, we realized that we could play at different dynamic levels. And then a lot of people started playing down there after that, and it kept happening.

Ownership of the club changed a couple of times over the years, and 37 years later I’m still playing there. It’s a really cool scene, and we’re really working hard to keep it happening. It looks like it survived the pandemic, so I guess we'll see what happens next there.

You no doubt canceled a lot of touring in 2020 because of the pandemic. Do you have any plans to resume touring?

I’ve got some gigs in March with Randy Brecker and Dennis Chambers. Other than that, I’m playing at the 55 Bar every Monday and Wednesday night.

Purchase Going for It by the Harvie S Trio here.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Bill Milkowski's first piece for Guitar Player was a profile on fellow Milwaukee native Daryl Stuermer, which appeared in the September 1976 issue. Over the decades he contributed numerous pieces to GP while also freelancing for various other music magazines. Bill is the author of biographies on Jaco Pastorius, Pat Martino, Keith Richards and Michael Brecker. He received the Jazz Journalist Association's Lifetime Achievement Award in 2011 and was a 2015 recipient of the Montreal Jazz Festival's Bruce Lundvall Award presented to a non-musician who has made an impact on the world of jazz or contributed to its development through their work in the performing arts, the recording industry or the media.

"Why can't we have more Django Reinhardts going, 'F*** everybody. I'll turn up when I feel like turning up'?" Happy birthday to Ritchie Blackmore. The guitar legend looks back on his career in an interview from our December 1996 issue

"Get off the stage!" The time Carlos Santana picked a fight with Kiss bassist Gene Simmons and caused one of the guitar world's strangest feuds