“I Was Always More Influenced by Horn Players and Piano Players”: Jazz Star Pasquale Grasso Reveals His Unique Inspirations

One of the most gifted and musical jazz guitarists of today takes inspiration not from his six-string brethren but from the genre’s legendary ivory ticklers

In 2015, I had the honor of being on a panel of judges for the First Annual Wes Montgomery International Guitar Competition, sponsored by George Klabin of Resonance Records and held in Merkin Concert Hall on Manhattan’s Upper West Side.

This evening showcased half a dozen rising-star guitarists from around the world, including Dan Wilson from Ohio, Michael Valeanu from France, Lucian Gray from Toronto and Roland Balogh from Budapest.

But of all the finalists that October day, one preternaturally gifted guitarist stood above the rest. In fact, after Pasquale Grasso from Italy finished his set, I elbowed fellow judge Pat Martino sitting next to me and said, “It’s all over. That’s the guy.”

And Pat agreed.

Grasso won the competition, taking home the $5,000 prize and a Pat Martino Signature Model Benedetto guitar.

It wasn’t long after that Wes competition that he was signed by Sony Music Masterworks, which led to a series of digital EPs commencing in 2019 with Solo Standards, Vol. 1, followed by Solo Ballads, Vol. 1, Solo Monk and Solo Holiday and continuing in 2020 and 2021 with tributes to jazz giants Bud Powell, Charlie Parker and Duke Ellington.

The latter is a trio outing with his longtime simpatico rhythm tandem of bassist Ari Roland and drummer Keith Balla, and featuring guest appearances by vocalists Sheila Jordan (on “Mood Indigo”) and Samara Joy (“Solitude”).

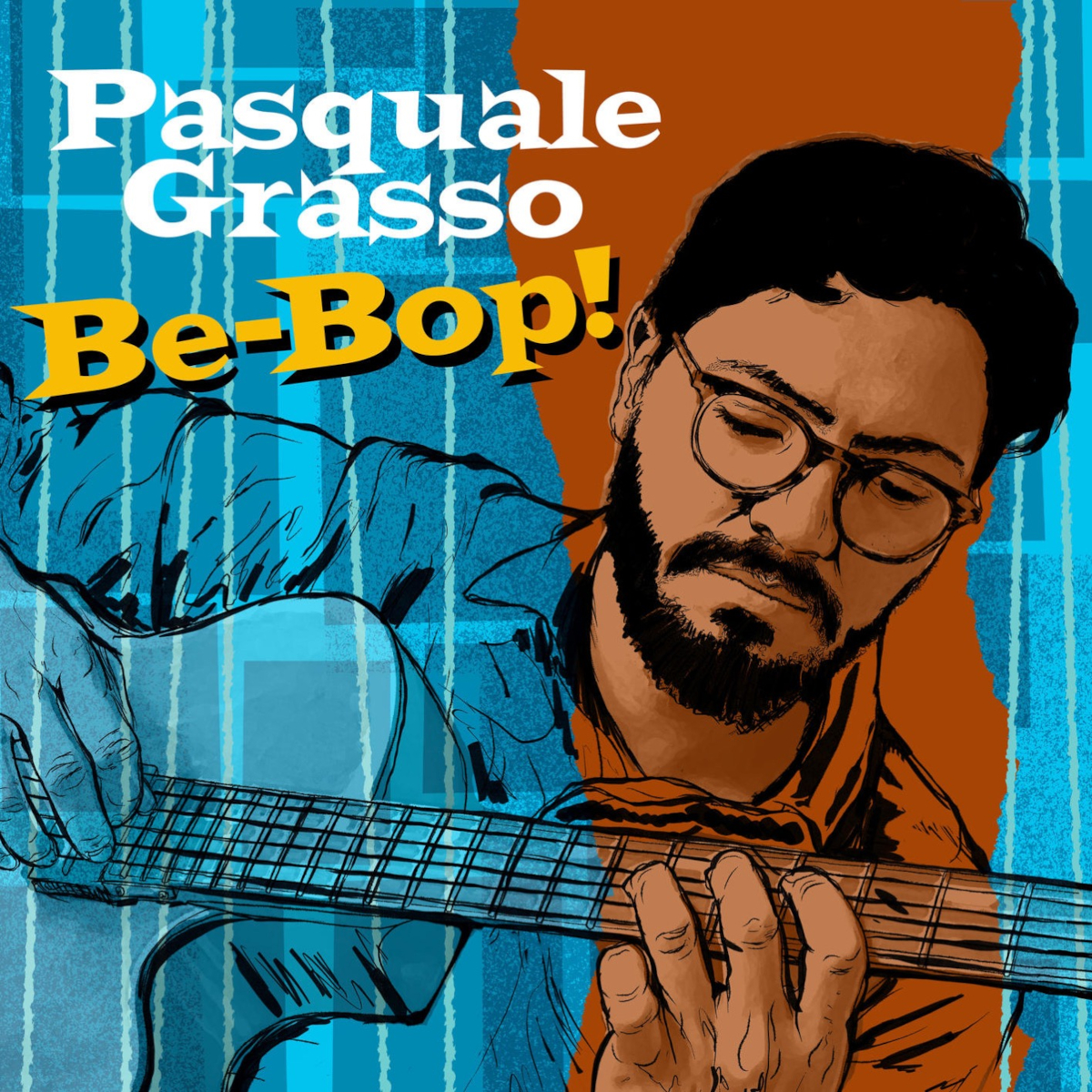

The trio returns with Be-Bop!, Grasso’s tribute to bop pioneers Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker.

This latest outing, which also marks the guitarist’s first physical album release by Sony Masterworks, kicks off in exhilarating fashion with a faithful reading of Dizzy’s “A Night in Tunisia.”

It’s a brilliant showcase for Grasso’s balance of technical wizardry and inherent swing, and his blazing solo break at the 1:03 mark is in the breathtaking tradition of Charlie Parker’s famous alto sax break from his 1946 Dial recording of the tune.

Pasquale’s stream of single notes that follows for the next two minutes in his solo is even more astounding, brimming with rare facility and abandon to match his fertile imagination.

He punctuates his solo with brief but dazzling quotes from one of Paganini’s Caprices (the extremely difficult No. 24 in A minor) in the coda to the tune.

Elsewhere on Be-Bop!, the trio is in sync through super up-tempo, challenging bop staples like “Shaw ‘Nuff,” “Groovin’ High,” “Cheryl,” “Ornithology” and “Be-bop.”

They settle into a more serene vibe on Thelonious Monk’s gorgeous ballad “Ruby, My Dear” and take Parker’s “Quasimodo” at a relaxed mid-tempo, with Grasso’s superb octave playing leading the way.

Be-Bop! stands as the next step in the brilliant career of one of the most technically gifted and supremely musical jazz guitarists on the scene.

As his producer, Matt Pierson, put it, “When I first head Pasquale, it was clear that he was doing something on the instrument that I’d never heard before. First, he was approaching the guitar in a revolutionary way, combining jazz and classical technique to pull off a very pianistic vision.

As is the case with the greatest artists, his mastery of both his instrument and his musical vocabulary was a means to an end

Matt Pierson, producer

“Second, as is the case with the greatest artists, his mastery of both his instrument and his musical vocabulary was a means to an end, a storytelling vehicle that is a direct extension of his own personality.

“As time goes on, each time I hear him play, I’m amazed how this emotional quality continues to deepen. And while he has gotten more advanced technically, the listener can feel more connected to him now.

“His phrases are more lyrical; I can feel him breathe, pausing to reflect as he’s telling his own story, leaving me hanging on that last note, dying to hear what he’ll say next.”

Born and raised in Ariano Irpino, in Southern Italy’s Campania region, Grasso relocated to New York in 2012 and has since been wowing audiences with regular appearances at Mezzrow, Smalls and the Django, where he has showcased his Joe Pass–ian command of the fretboard by freely moving between single notes, chords and independent bass lines while flashing Art Tatum-esque filigrees with uncanny speed and precision.

Grasso’s main jazz guitar is a custom Trenier archtop called the Modello Pasquale Grasso model, made by French luthier Bryant Trenier.

“I like big guitars,” Grasso says. “I like to feel the vibration go to my chest. That’s one of the most beautiful feelings when I play.”

His amp is a 1953 Gibson GA50, and he uses LaBella strings.

Where does your very pianistic approach to the guitar come from?

Since I was a little kid, I always had this sound in my head. Slowly, it’s coming out, but it’s still not what I want.

I was never too influenced by guitar players, for some reason. I grew up listening to Art Tatum, Bud Powell and Thelonious Monk. Those were my guys.

For guitar, I always liked Charlie Christian and Oscar Moore, but I never really listened too much to guitar players. Of course, when I hear Barney Kessel and Chuck Wayne and Jimmy Raney, I love them. They’re all great artists, but they never really got me when I was a kid. I was more into Bird and Bud, Dizzy Gillespie, Roy Eldridge and Louis Armstrong.

I was never too influenced by guitar players, for some reason

Pasquale Grasso

Of course, when I got Joe Pass’s Virtuoso, I was very shocked. I had never heard a guitar player play in this way. It’s the same with Wes Montgomery. I love Wes so much: his tone, his phrasing. I love everything that he plays.

So I was always more influenced by horn players and piano players than guitar players.

When I first heard you perform live, the Joe Pass comparison immediately sprung to mind because of the independence of chords, bass lines and melody. Was Joe at all an influence on you?

Of course, I love Joe Pass. I was very amazed by the touch that he had on the guitar. This is something very special. But I wouldn’t say I was influenced by that.

But I would never play in that kind of guitar style. It’s just not who I am. It’s not what I want to do. And, for some reason, I always preferred to listen to Art Tatum. It’s just a different feeling that it gives me when I hear him, or when I hear Bud Powell playing solo. It’s just their sound.

Of course, nobody can be Art Tatum. He’s a true genius – a creation of god. But I always try to catch some of his runs and some of his chords and harmonies and this swinging feeling that he gets on the piano. There’s just something about the sound of that I always liked, and I tried to transfer that onto the guitar.

In terms of guitar players, I’d rather hear a classical guitar playing a [Matteo] Carcassi song or a [Mauro] Giuliani song, and that makes me very inspired, because of the way that they play counterpoint and stuff like that.

When you cite Bud Powell as a major influence, are you referring to the very speedy single-note lines or the chord voicings and advanced harmonies in his playing?

Bud has been my inspiration ever since I was six years old. Everything that he plays – single lines, chords, his compositions – has influenced me. And the same thing with Monk and Art Tatum and Teddy Wilson. There’s just something about the piano.

I studied with a great piano player, Barry Harris, when I was nine years old. That was always the sound that I liked, and I tried to transfer that onto the guitar.

There was just something about the shape of the guitar that attracted me, and that’s what I chose

Pasquale Grasso

But I’m curious: How does a six-year-old kid even know about Bud Powell, especially growing up in Southern Italy?

That’s funny, I know. My dad and my mom love music. When my dad was young, he went to Canada and he brought all this jazz vinyl back home, because he always liked jazz. So we grew up with all these great jazz records that he would play for us, and he saw that my brother, Luigi, and I really liked that kind of music, so he wanted to support us.

My brother, who is two years older than me, started with saxophone when he was six years old. I was four and a half when I told my dad I wanted to play music. So he brought me to this instrument store and said, “Choose whatever you like.”

He actually wanted me to play trumpet, but when I saw the guitar, I told him, “I want to play this.” There was just something about the shape of the guitar that attracted me, and that’s what I chose.

What was your early music training like?

Luigi and I grew up playing and practicing together. It was a game for us. My mom learned how to read music. There was no music school in the village where we grew up, so she got a book and she taught us how to read music.

She would sit for a couple of hours a day every day and say, “Okay, you’re going to learn the scales… You’re going to learn to read.” And my mom realized early on that both of us had perfect pitch, so it was really easy for us to learn music.

Both my parents grew up in a little town where nobody even knows jazz, but somehow they have a great love for this music. And I keep asking myself, Where does this come from? How is it possible that two people from the middle of nowhere in Italy got into jazz? And then they transmitted their love of jazz to me and my brother. That’s really amazing.

We drove all the way to Switzerland to do this workshop

Pasquale Grasso

What were the circumstances that led to you studying with Barry Harris at the age of nine?

Luigi had a sax competition when he was eight, and in the competition was a great guitar player from New York named Agostino Di Giorgio, who had moved to Italy to take care of his grandparents. My dad asked him if I could take some lessons.

Agostino was a student of Chuck Wayne, the great guitarist from the ’40s. And so me and Luigi ended up taking lessons from Agostino, who lived in Rome, which was about a three-and-a-half-hour drive from where we lived in Arpino.

He would teach me guitar and teach harmony to both of us. One day, Agostina said, “Barry Harris is coming to do a workshop in Switzerland. You guys should go there.” And my dad, being a jazz fan, knew the name of Barry Harris, so he said, “I’m going to bring you guys there.”

So we drove all the way to Switzerland to do this workshop. I remember walking into the room on the first day, and Barry was playing “I Want to Be Happy.” And me and Luigi looked at each other and said, “We’re in the right place!”

What kind of records did your father have in his collection?

He had some Charlie Parker and Louis Armstrong, and he’s a big fan of trumpet, so he had records by Chet Baker, Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie and Fats Navarro. He also had some George Benson records.

Actually, my first love was George Benson, because my dad had this vinyl copy of one of his first recordings, with Jimmy Lovelace on drums and Ronnie Cuber on baritone sax and Lonnie Smith on organ.

My first love was George Benson

Pasquale Grasso

That was The George Benson Cookbook, with that burning opening track, “The Cooker.”

Exactly! That was my first love. And then I heard Jazz at Massey Hall with Bird and Bud, Charles Mingus, Max Roach and Dizzy Gillespie, and it just got me so bad, you know?

After that, all I wanted to do was play like Charlie Parker and Bud Powell.

You are mostly known for your virtuosic solo series of digital EPs that have come out on Sony Music Masterworks. But on last year’s Ellington tribute, Pasquale Plays Duke, you introduced your trio for the first time on record. What can you tell us about them?

I met Ari [Roland] and Keith [Balla] when I first got to NYC in 2012... It’s an inspiration to be around them

Pasquale Grasso

I met Ari and Keith when I first got to NYC in 2012. My good friend Stefano Doglioni, who is a terrific bass clarinet player, introduced me to them, and we had an instant musical connection. I started hiring Ari and Keith for my local NYC gigs.

We have met nearly every day to jam together for the past 10 years. I love them as people, and they bring out the best in me when I play with them. It’s an inspiration to be around them.

I love playing solo, but it’s easier to play with the rhythm section because I have more freedom. When you play solo, you have to play chords and play the melody; you have to do everything by yourself. But when you play with a rhythm section, you can play more like a horn player.

That horn-like quality is apparent on the opening track to the Duke tribute album, “It Don’t Mean a Thing.” You’re playing more single notes and, of course, you don’t have to play so pianistically and cover baselines and chords and melody at the same time.

I play the same way that I play solo with the trio. It’s a little different because I can focus on improvisation and just be more free when I take my solo.

I love playing solo, but it’s easier to play with the rhythm section because I have more freedom

Pasquale Grasso

Thinking back to your development as a guitarist, was there a moment when you had a breakthrough in terms of the independence that you’ve attained on the instrument?

What helped me a lot was studying classical guitar. Agostino is a great jazz player and a great teacher, but what really turned me around was when my dad took me to a concert of the great classical guitarist David Russell.

I was sitting, like, five feet from him, and what I realized is that he had so much command of the instrument. He could play the melody, he could play chords, he could play counterpoint.

I was about to go and study chemistry for college, but then I thought, I’m going to go and study classical guitar instead, and that’s going to help me figure out what I want to do with with jazz.

Order Pasquale Grasso’s Bep-Bop! here.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Bill Milkowski's first piece for Guitar Player was a profile on fellow Milwaukee native Daryl Stuermer, which appeared in the September 1976 issue. Over the decades he contributed numerous pieces to GP while also freelancing for various other music magazines. Bill is the author of biographies on Jaco Pastorius, Pat Martino, Keith Richards and Michael Brecker. He received the Jazz Journalist Association's Lifetime Achievement Award in 2011 and was a 2015 recipient of the Montreal Jazz Festival's Bruce Lundvall Award presented to a non-musician who has made an impact on the world of jazz or contributed to its development through their work in the performing arts, the recording industry or the media.

“I knew he was going to be somebody then. He had that star quality”: Ritchie Blackmore on his first meeting with Jimmy Page and early recording sessions with Jeff Beck

“He used to send me to my room to practice my vibrato.” His father is the late Irish blues guitar great Gary Moore. But Jack Moore is cutting his own path with a Les Paul in his hands