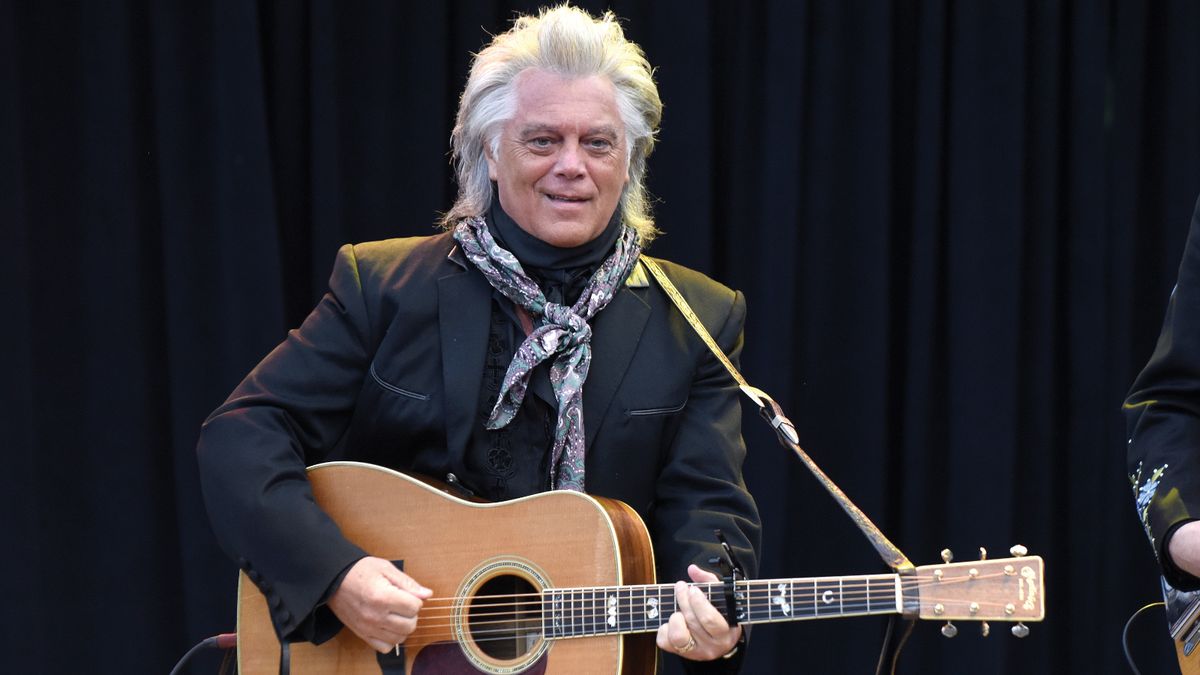

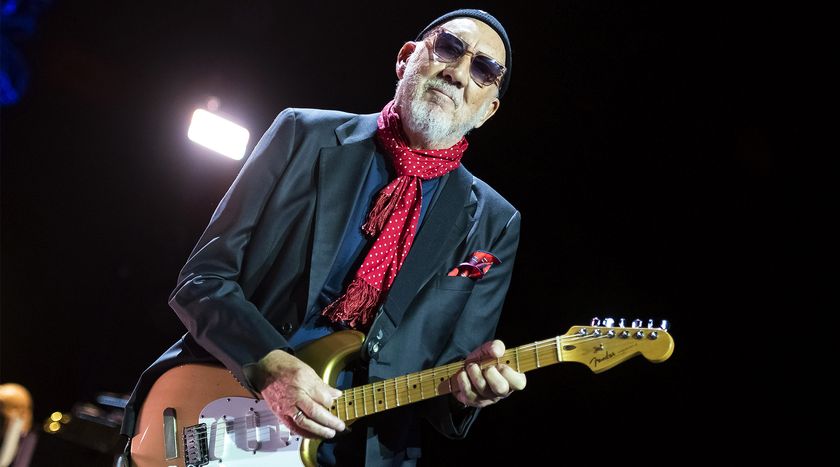

“I Put the Electric Guitar off to the Side for a While and Fell in Love With Bluegrass”: Marty Stuart Reflects on His Deep Connection to Country Music’s History

The Martin acoustic guitar stalwart is connected to practically everyone that matters in country music, going all the way back to his original hero, bluegrass pioneer Bill Monroe

***The following appeared in the Holiday 2019 issue of Guitar Player***

Marty Stuart may be the Forrest Gump of country music. The mandolin and guitar plucker’s presence at key moments over the decades is uncanny, from his prodigious teenage years working with Lester Flatt to his subsequent tenure in Johnny Cash’s band and his eventual emergence as a bona fide solo star.

Stuart is a respected historian, instrument aficionado and flame keeper, so it’s easy to see why Ken Burns turned to him often throughout his Country Music documentary.

Stuart appears in the film many times with his mandolin or an acoustic guitar in hand to exemplify musical matters and offer anecdotes based on his own singular history.

“We call him ‘Zelig’ because he’s everywhere,” Burns told me when I interviewed him and Vince Gill. (The reference, of course, is to Woody Allen’s fictional human chameleon, who shows up at key historic moments in the 20th century.)

Chalk it up as further evidence that Marty Stuart is connected to practically everyone that matters in country music, going all the way back to his original hero, bluegrass pioneer Bill Monroe.

Back in 2019, Guitar Player caught up with Stuart while he was burning up the road with his aptly named Fabulous Superlatives band in support of their Mike Campbell-produced 2017 studio release, Way Out West.

Can you explain what Monroe did on mandolin that was so revolutionary?

Until that point, the mandolin was associated with either an Italian Renaissance style played on a belly-back mandolin, or as part of a mandolin orchestra, which was kind of the rage in some regions of the nation during the early 20th century. Monroe put more of a fiddle tune aspect to it, and he revved it up.

A lot of people have come through the gates of Nashville with hit songs and sounds, but hardly anyone had such a distinct brand that it developed into a new genre, a tributary off the mainstream of country music that has gone on to become kind of a national language. I may or may not have mentioned it in the film, but I believe Bill Monroe achieved that.

Gene Autry once told me, 'I wasn’t the best cowboy actor or cowboy singer, but I was pretty much the first, and the rest of it don’t matter'

Marty Stuart

Players with perhaps more technical prowess have come and gone. As Gene Autry once told me, “I wasn’t the best cowboy actor or cowboy singer, but I was pretty much the first, and the rest of it don’t matter.” Monroe has a similar claim.

Your career starts with Lester Flatt, who was the seminal guitar player in Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys before he broke away with banjo star Earl Scruggs. Can you share some insights on the importance of Flatt’s guitar?

The Monroe brothers with Charlie [Monroe] on guitar had set the sound before Bill went out on his own. Clyde Moody preceded Lester on guitar in the Blue Grass Boys, and both were students of the Charlie Monroe school of guitar. He was a fingerpicker who used a thumb pick, so that set the stage for the whole Monroe sound.

Lester was an awesome rhythm player. He played what I call “invisible rhythm” because it was overshadowed by all the lead playing going on between Earl, Uncle Josh and [fiddler] Paul Warren. But I promise you this: If Lester quit playing, a hole about the size of Oregon appeared in the band.

For a while he played the company guitar, which was Monroe’s herringbone. Then he had a D-18, but Lester’s main guitar down through the years was a D-28 that I actually owned and donated to the Country Music Hall of Fame for the Precious Jewels exhibit. Lester was a Martin man all the way.

What’s that little Martin you’re holding in Country Music at the start of episode seven?

It’s a 1953 Martin 5/18 that belongs to my wife, Connie Smith. Connie bought it on tour in the early ’60s because Marty Robbins played one, and she liked carrying it along with her in the backseat of the car. She’s pictured playing it on the cover of her album, If It Ain't Love and Other Great Dallas Frazier Songs.

My grandpa Stuart was a scratchy old-time Mississippi fiddle player, and my dad loved the sound of the mandolin, so it kind of became a thing

Marty Stuart

I have it in my hand as we speak, and it’s in standard tuning. Chris Scruggs [Earl’s grandson] is here with me, and he brings to mind that it was meant to be tuned up to G [a minor third].

It’s crazy that you were named after Marty Robbins, that you predicted your marriage to Connie Smith as a boy and were seemingly destined to be a country star from day one. [Stuart was 12 when he saw Smith, then 29, play a fair in his hometown, and told his mother he would marry her one day.] What was your first experience as a player?

I started out playing electric guitar in the neighborhood band when I was nine. We performed songs by Merle Haggard, Johnny Cash, Buck Owens and the Carter Family. Somehow I wound up buying a scratched-up 78 of Bill Monroe and the Blue Grass Quartet doing “The Wicked Path of Sin,” at a salvage store in Philadelphia, Mississippi. I fell in love with bluegrass music.

My grandpa Stuart was a scratchy old-time Mississippi fiddle player, and my dad loved the sound of the mandolin, so it kind of became a thing. When I got my mandolin and finally figured out a few chords on it, I put the electric guitar off to the side for a while and fell in love with bluegrass music all over again.

It was so obscure in that region of Mississippi that when a real bluegrass act would come through, it was an event. When I was 12 years old, my dad took me to see Bill Monroe and the Blue Grass Boys. After the set, I went over to where they were selling their records and bought one. Bill looked at me and said, “You really want to play the music, don’t you?” “Yes sir, I do,” I said. “I want to play the mandolin, just like you.”

Bill Monroe looked at me and said, 'You really want to play the music, don’t you?' 'Yes sir, I do,' I said. 'I want to play the mandolin, just like you'

Marty Stuart

He had one of those tri-corner guitar picks. It was white and kind of worn. He said, “Will you take this home and learn how to use it?” And I did. It was like having magic in my pocket. It was my secret. It empowered me.

Only a year or so later you landed the gig playing with Lester Flatt, and you mention being tutored by Monroe. How did that go down?

Lester Flatt and Bill Monroe did several package tours together right after I joined Lester’s band. The buses would travel in tandem. I would often ride along in the bus with Bill, and we’d play mandolin songs.

In Country Music, you mention playing a call-and-response game to learn licks, and that Bill kept one mandolin tuned standard and another in the “ancient tones.” Can you elaborate?

He came up with several wonderfully obscure tunings in what I’ve called the ancient tones because they really did sound ancient. He had developed mandolin and/or fiddle songs around those tunings, and one that I fell in love with was called “My Last Days on Earth.” I don’t have a clue what the tuning is at the moment, but I can do it on my mandolin if I sit there and wind on it long enough.

At one point in my career I had a Lloyd Loar, but I sold it and went back to my $650 copy

Marty Stuart

Can you share some details about your mandolin?

My main mandolin is a $650 [Gibson] F-5 copy that I bought in 1972 from Roland White. A luthier named Chris Warner made it in Pennsylvania. At one point in my career I had a Lloyd Loar, but I sold it and went back to my $650 copy. That’s one of the only material possessions that has made the entire journey with me.

John [Johnny Cash] was the first person to scratch his name on my mandolin. He put JRC, for John R. Cash, and then it became a guest book. There are a lot of notable people on that mandolin, and a few that people don’t know.

Are you still using the prototype of your signature Martin as your main stage guitar?

Yes, it’s a D-28. I worked on the design with Dick Boak at Martin, and I borrowed a bit from the Gretsch idea. I was looking for a guitar with a neck that would allow me to play Telecaster-style leads on it. I drew a rough concept and took it to a pearl artist named Diane Patrick, who helped me develop the fingerboard. Martin produced 250 of those guitars.

Pre/order Marty Stuart's forthcoming album, Altitude, here.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Jimmy Leslie has been Frets editor since 2016. See many Guitar Player- and Frets-related videos on his YouTube channel, and learn about his acoustic/electric rock group at spirithustler.com.

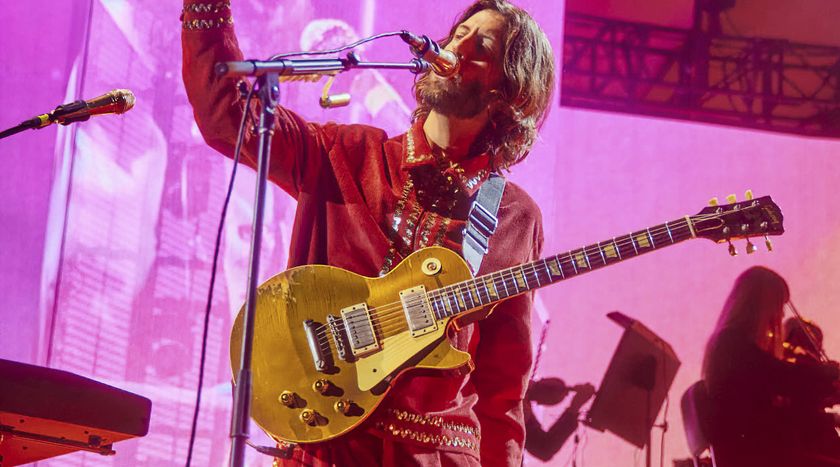

"Shane called me and said, 'The guitar is here. It plays amazing. It's providence calling!’” How an extremely rare goldtop 1958 Les Paul Standard found its way into the hands of Imagine Dragons guitarist Wayne Sermon

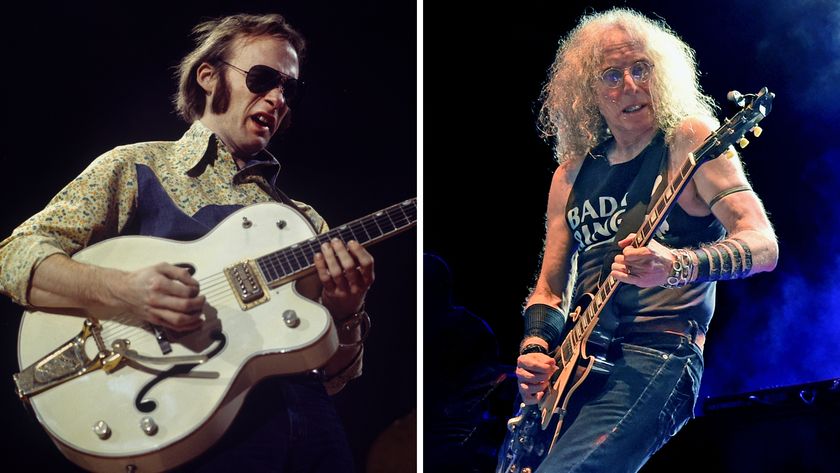

“A lot of Who fans would be really pleased.” Pete Townshend ponders using AI to re-create his ‘70s heyday for fans who prefer the Who's classic songs