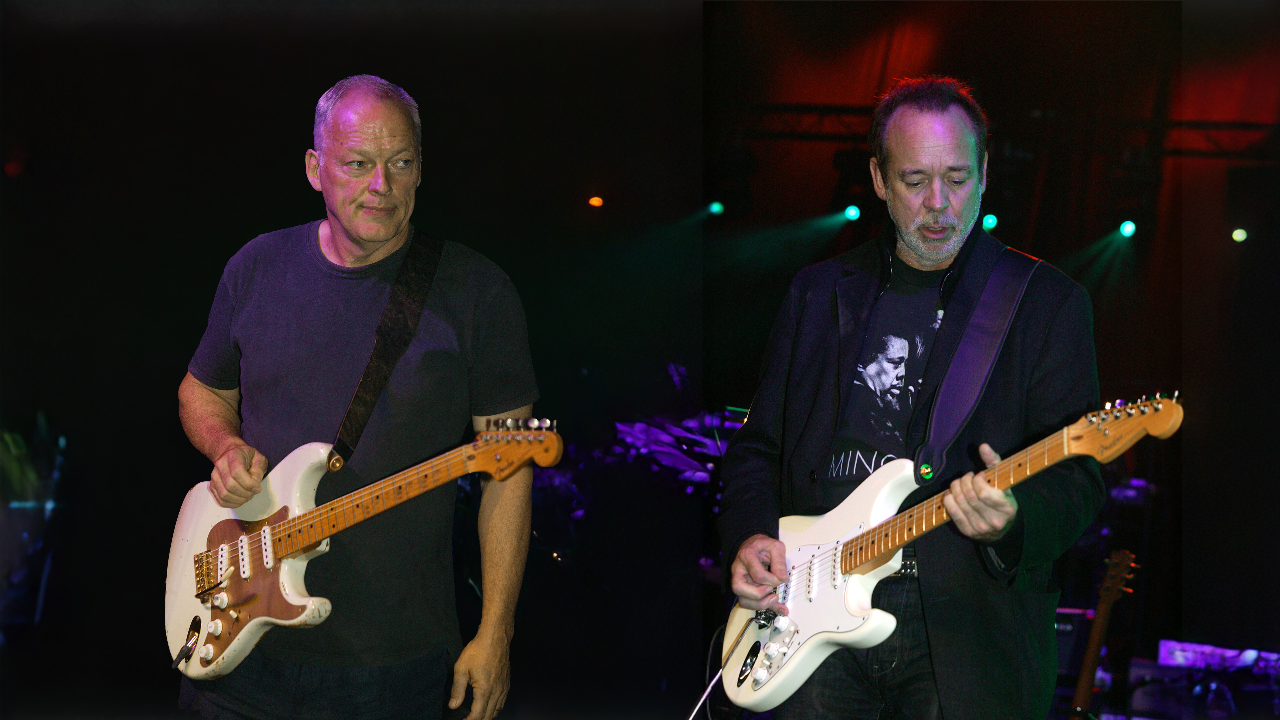

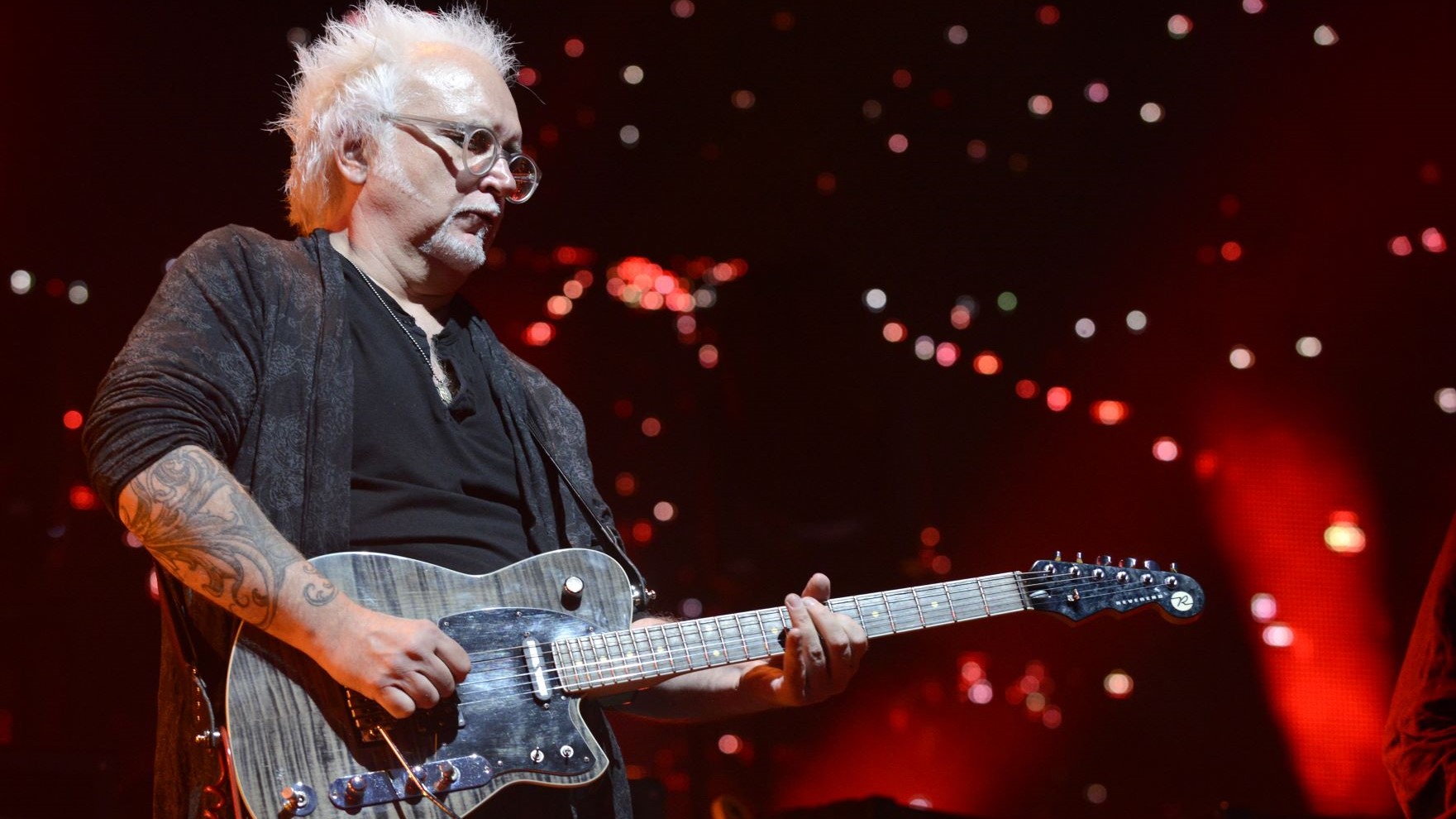

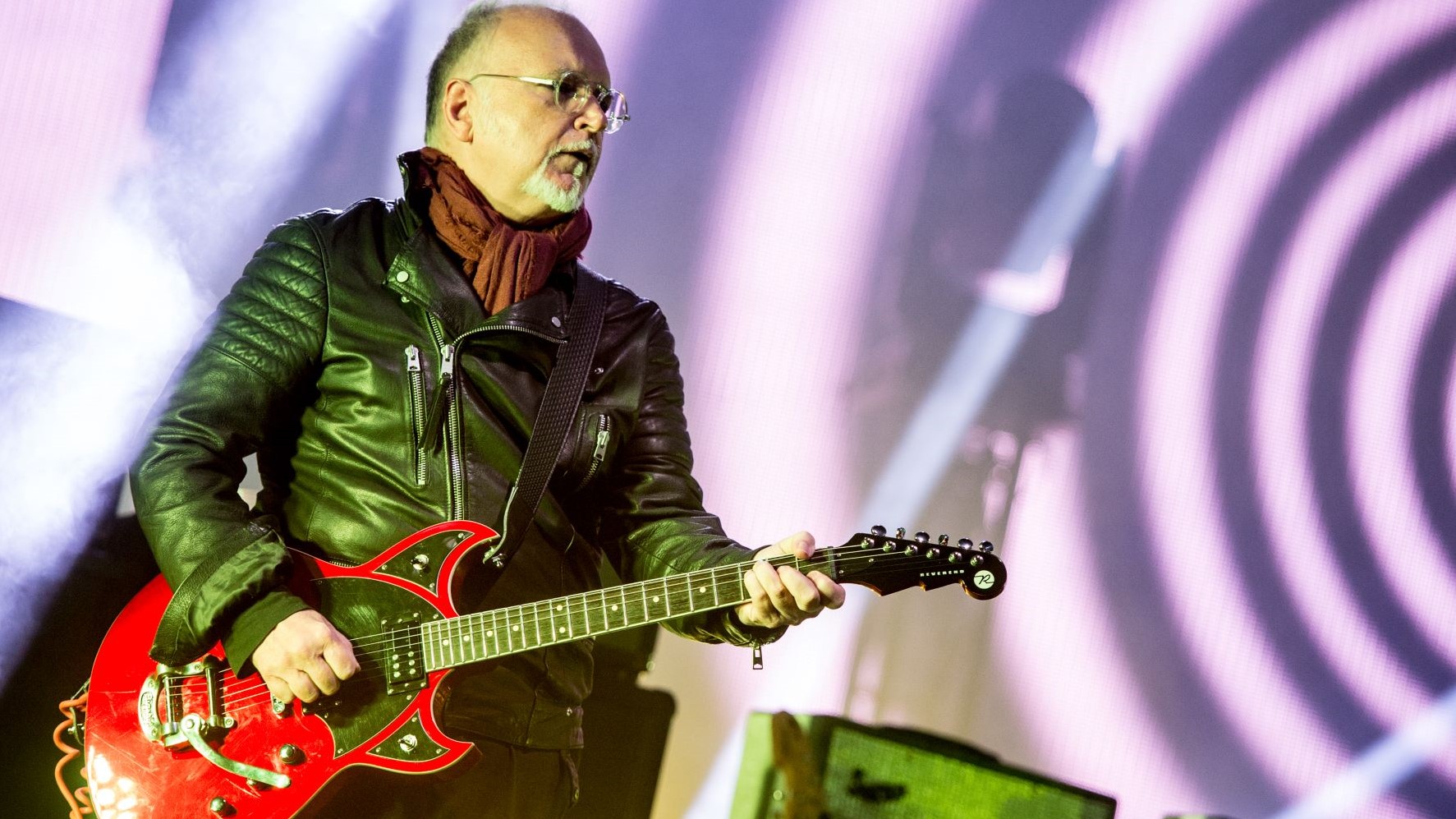

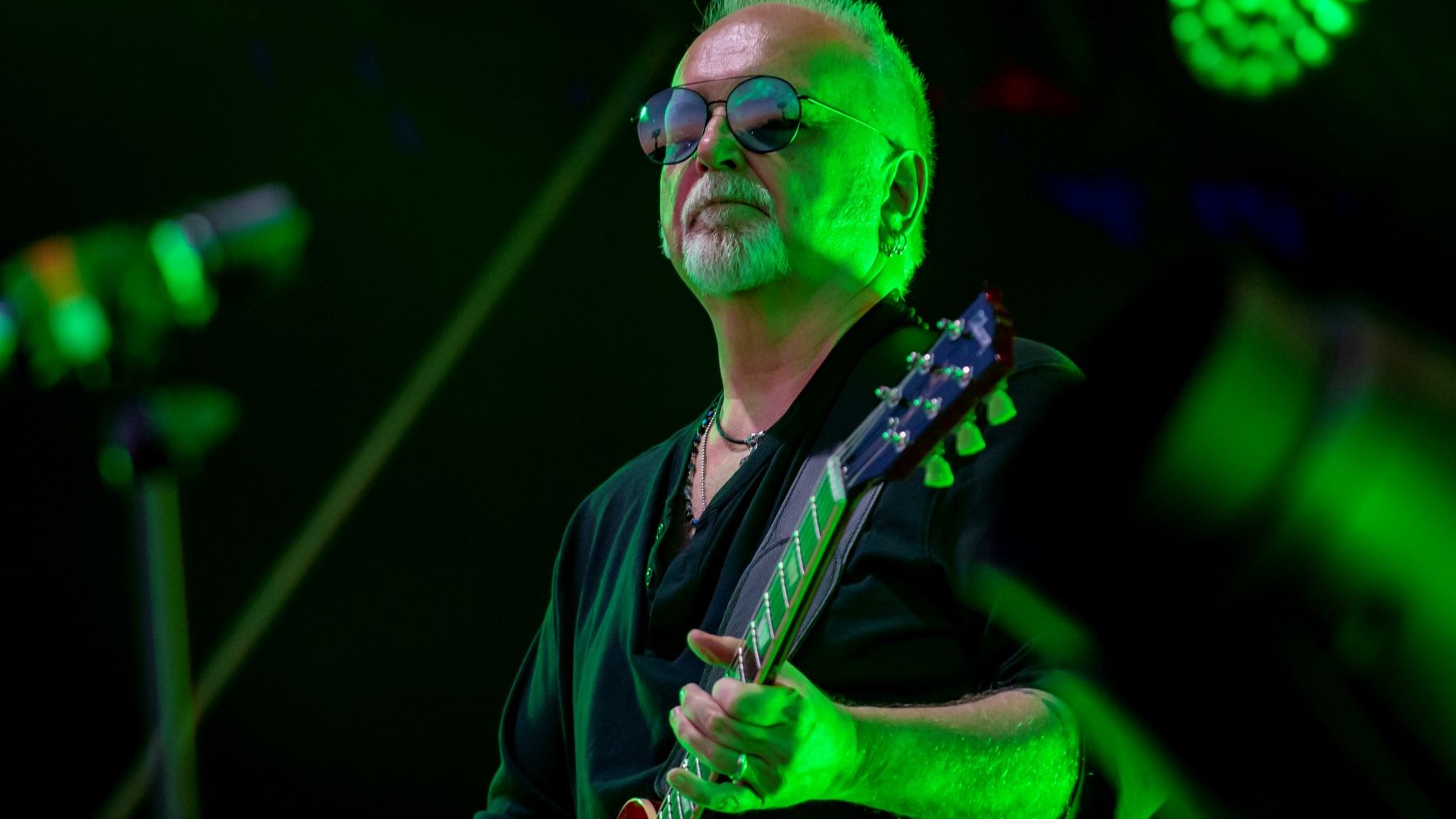

We were always very forward-thinking about the music we made together,” Reeves Gabrels says of his 10-year creative partnership with David Bowie. Beginning in 1989 with metallic hard-rock band Tin Machine, their alliance continued into the ’90s, when Gabrels co-produced a number of Bowie’s solo albums.

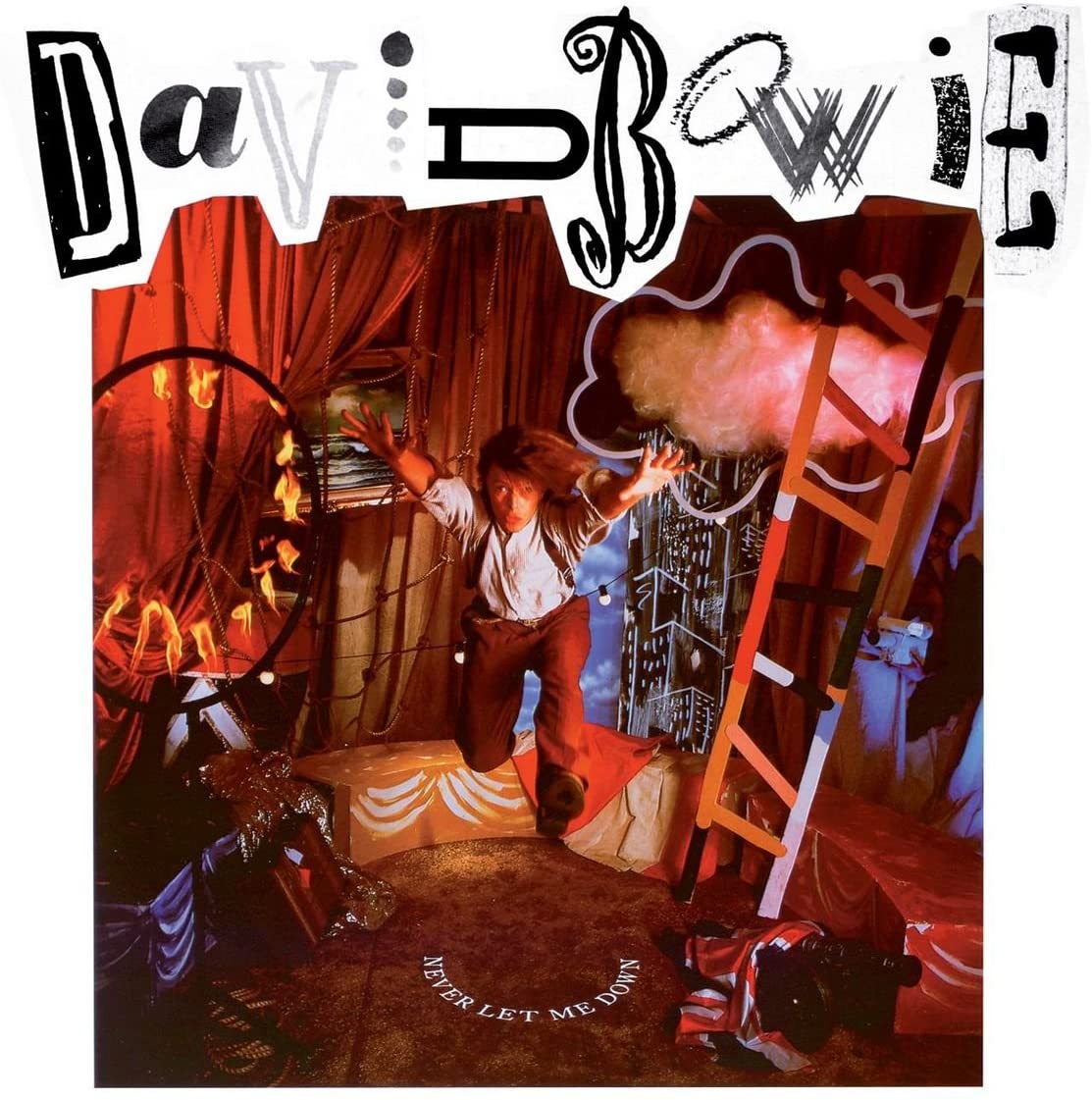

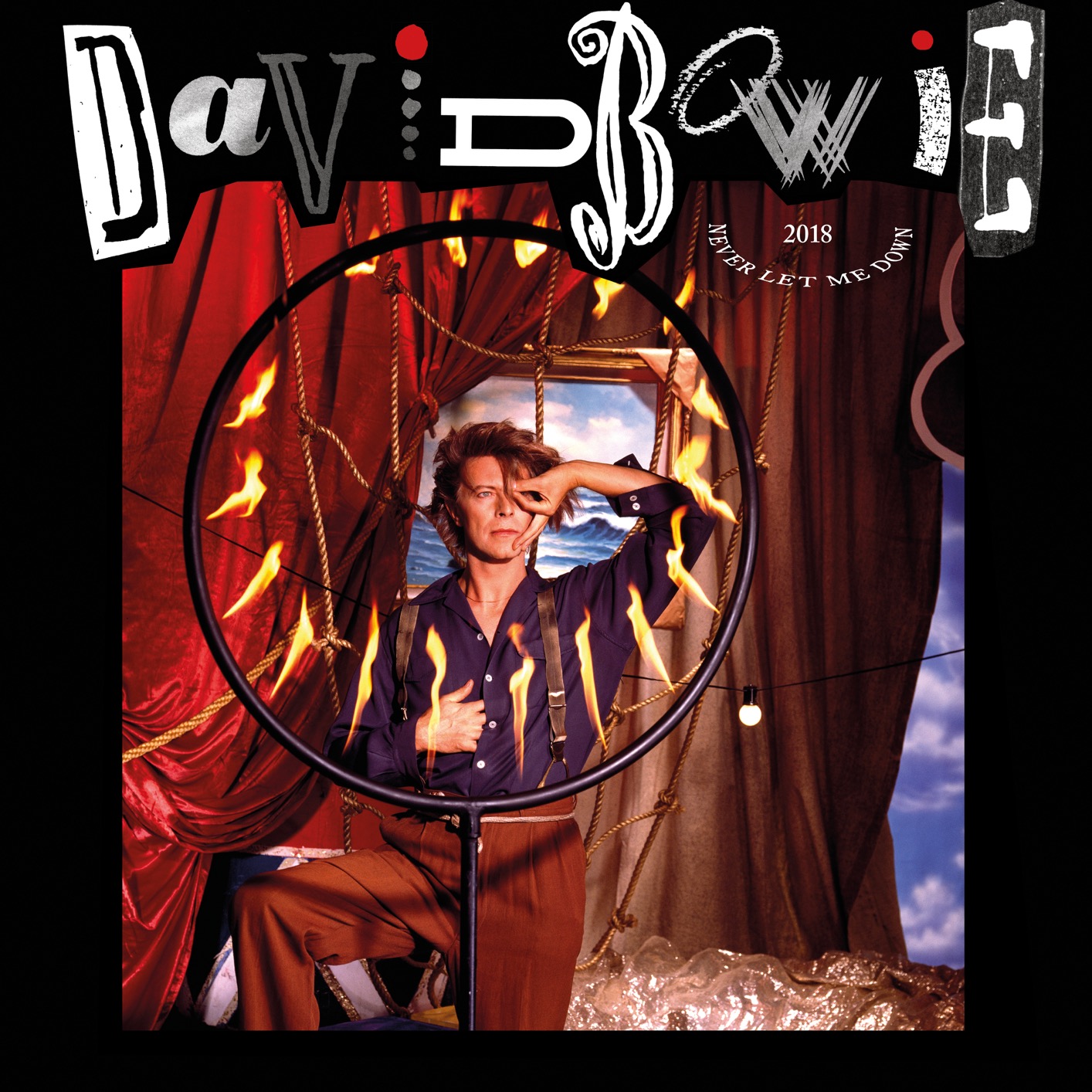

“Our whole thing was very much rooted in being in the moment. There wasn’t a lot of looking back going on between us.” Even so, Bowie told Gabrels he’d like to return to the studio and redo some songs from his 1987 album, Never Let Me Down. “The record seemed to gnaw at David a bit,” Gabrels recalls. “He’d had such a big hit with ‘Let’s Dance,’ and I think he felt obliged to follow up that success on Tonight and Never Let Me Down, but I think he did so half-heartedly. He told me that he’d kind of checked out mentally during the recording of Never Let Me Down, and he wanted a chance to take a mulligan. He would always say, ‘I just know there’s some good songs on it. I wouldn’t mind redoing some of them.’”

Gabrels knew what he meant. When he first heard the album, before working with Bowie, he and his “smart-ass musician friends” compared notes on the record. “We were like, ‘Gee, it’s 1987, but this seems a little 1985,’” he says. “It was very synthy, a little too Duran Duran-ish, if you will. But when I saw David perform tracks from the album on the [1987] Glass Spider tour, the music came off more muscular live than on record. It had grit to it. So I could see where he was coming from about revisiting those songs. It just wasn’t something I thought I should be a part of, and I always shot it down.”

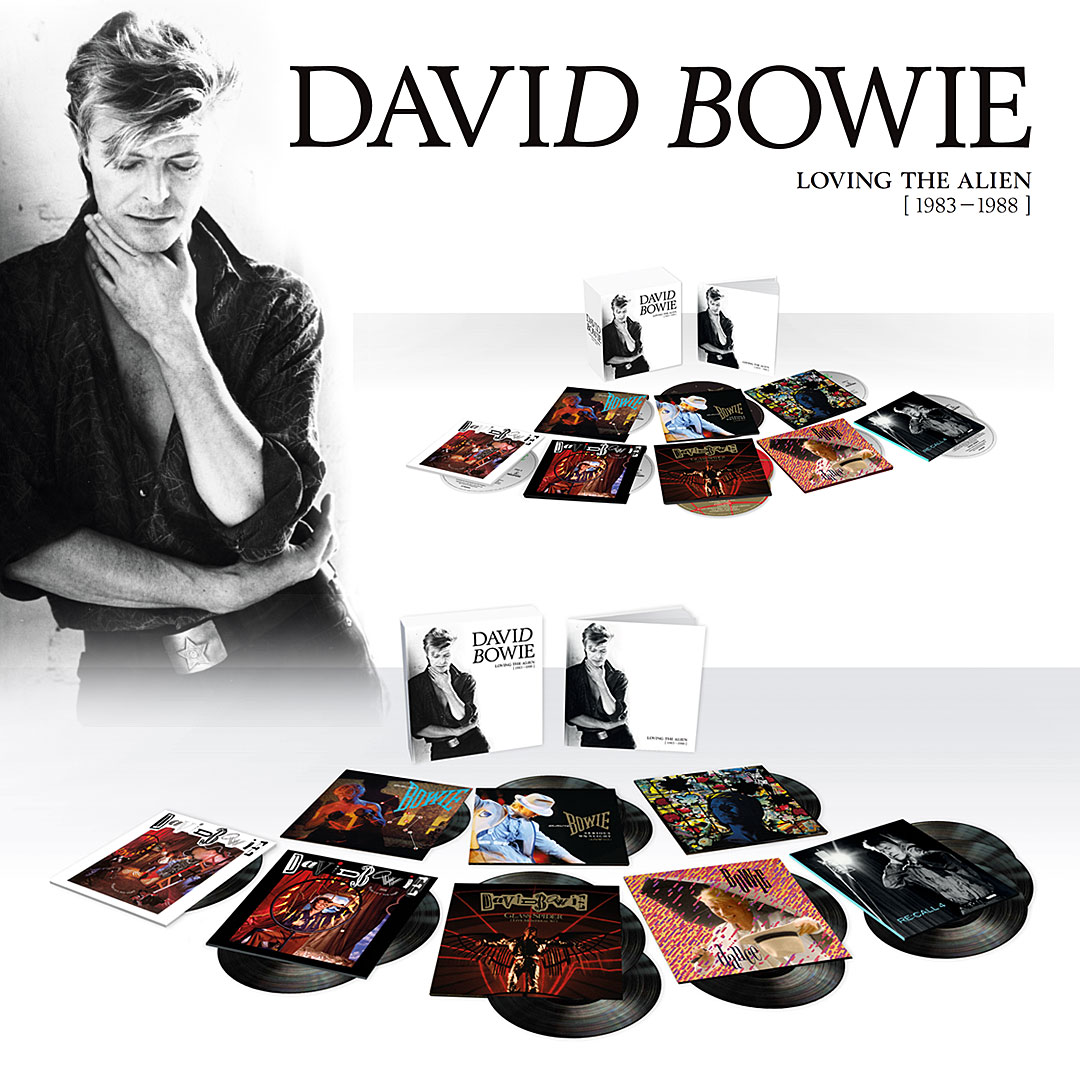

Much to his surprise, and delight, Gabrels later took part in reworking not just a few songs from Never Let Me Down but the entire album. Titled Never Let Me Down 2018, the disc is part of the elaborately packaged box set David Bowie: Loving the Alien (1983–1988), the fourth in a series of retrospectives spanning the singer’s career from 1969 forward.

Guided by producer/engineer Mario McNulty, who had collaborated with Bowie in 2008 on a remix of the album track “Time Will Crawl,” Gabrels joined guitarist David Torn, drummer Sterling Campbell and bassist Tim Lefebvre – all selected by Bowie, in notes written before his passing in January 2016 – to breathe new life into the tracks that had plagued the singer over the years.

Recorded at Electric Lady Studios in New York City, the resulting album is a punchier, far more guitar-heavy affair than its synth-laden original. Gabrels feels that Bowie would approve. “We absolutely tried to respect David’s wishes with this new version of the album,” he says. “What’s kind of funny is, we sort of went into this process with a veil of secrecy about what we were up to. I think the label people believed we were doing more of a remix than a whole re-imaging of the album, and we totally blew their minds when they heard it. David would be pleased by that, I think.”

So how did this project come about, and what led to you finally saying yes?

According to everyone involved in the Bowie estate trust, when David knew that he was dying, he left a five-year plan behind of what he wanted done with his music. From what I understand from Mario, he wrote out instructions to remake this record, and there was a list of musicians that he wanted. All of the people are post-1987 musicians. They’re the next gen.

Mario explained this to me. We met at Dean & DeLuca and talked for five hours about it. At first, I still felt like it wasn’t my place to get involved with stuff I hadn’t been a part of. Now, there is some precedent for this: The first thing I did with David was a remake of “Look Back in Anger,” but that wasn’t supposed to appear on a record, though it has subsequently appeared on [the 1991 reissue of] Lodger. My rearrangement of it was for a dance company presentation that David did.

So when this idea was presented to me, my reaction was, ‘Ah, this is rich! This is David’s final practical joke on me for all the times I said no. He knows I’m not going to say no to a dead man.’” [laughs] But then Mario played me the remix of “Time Will Crawl,” and I saw what the approach was – stripping it back, recording brand-new guitars, bass and real drums, and then getting rid of everything except what David played. So I came around and said, “I’m in.”

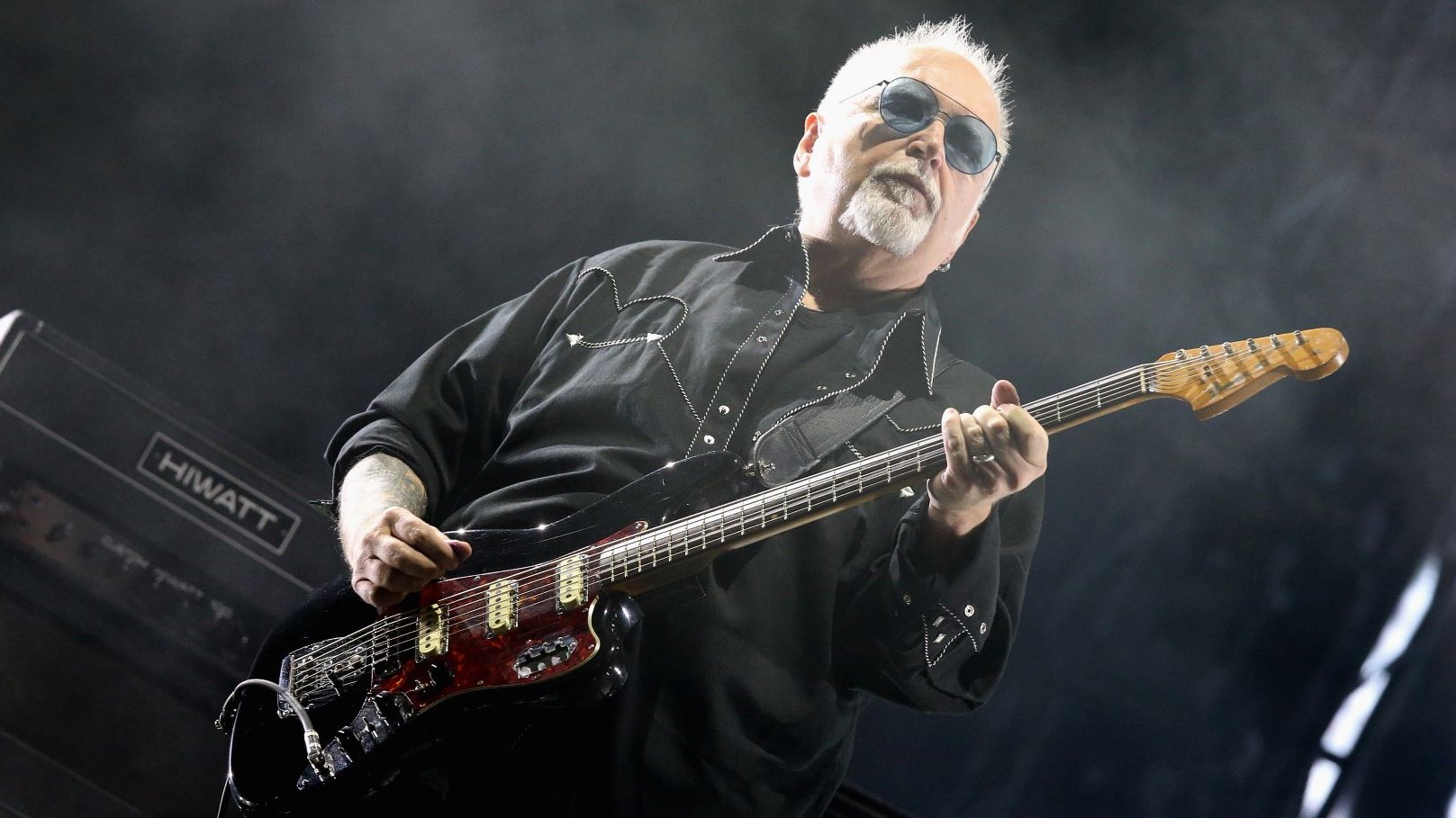

How did you and David Torn divvy up your guitar duties? You two had never worked together before, right?

No. We tried to recognize each other’s strengths and not get into any overlap. Torn was more the “clouds of frozen remorse” guy, whereas I was the “bull in the China shop, foot on the monitor” kind of guy. We did a lot of stuff independently, but there was one day we both recorded together at Electric Lady. We improvised textures simultaneously, trying to wrap ourselves around each other. I think I did more of a metallic kind of groove, and Torn did a sort of reverbed, tape-manipulated texture.

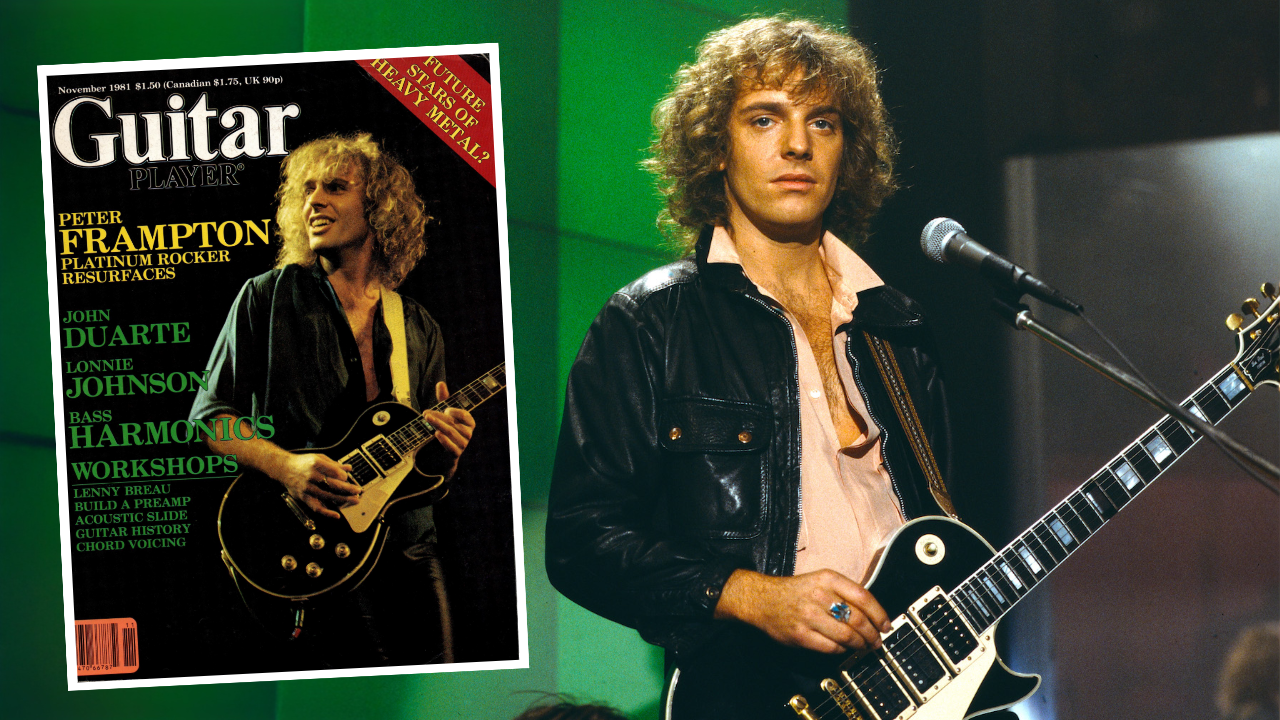

Did you keep any of the original guitar tracks by Carlos Alomar and Peter Frampton?

On "Zeroes" we kept Peter’s sitar, because to me that part was so ingrained in the song. If I had played it, I would have done something pretty much the same. And Carlos played a gated rhythm part on “Never Let Me Down” that just moved the song in the same way that Johnny Marr’s part on [the Smiths’] “How Soon Is Now?” does for that song, so it made sense to keep it. We weren’t trying to be cruel or destroy the original document, but this was David’s wish, so that absolved us from any guilt we might have had.

I didn’t listen to the original album before I went in the studio; I wanted to treat the whole thing like a demo.

Reeves Gabrels

The synths are de-emphasized on “Day-In Day-Out,” but there are some parts that sound like keyboards – although they could be electric guitars.

Yeah, I know what you mean. We didn’t really keep any of the original synth stuff from the album. A lot of those textures are guitar-played or stuff that Mario did after the fact. The part you’re talking about – it sounds like a baritone sax or a synth – that’s actually an Alexander Syntax Error pedal. That just came to me, and it sounded right. You see, I didn’t listen to the original album before I went in the studio; I wanted to treat the whole thing like a demo. I didn’t want to be too married to what had been done before, because then I’d just try to re-create new versions of what had been done.

How did you approach “New York’s in Love”?

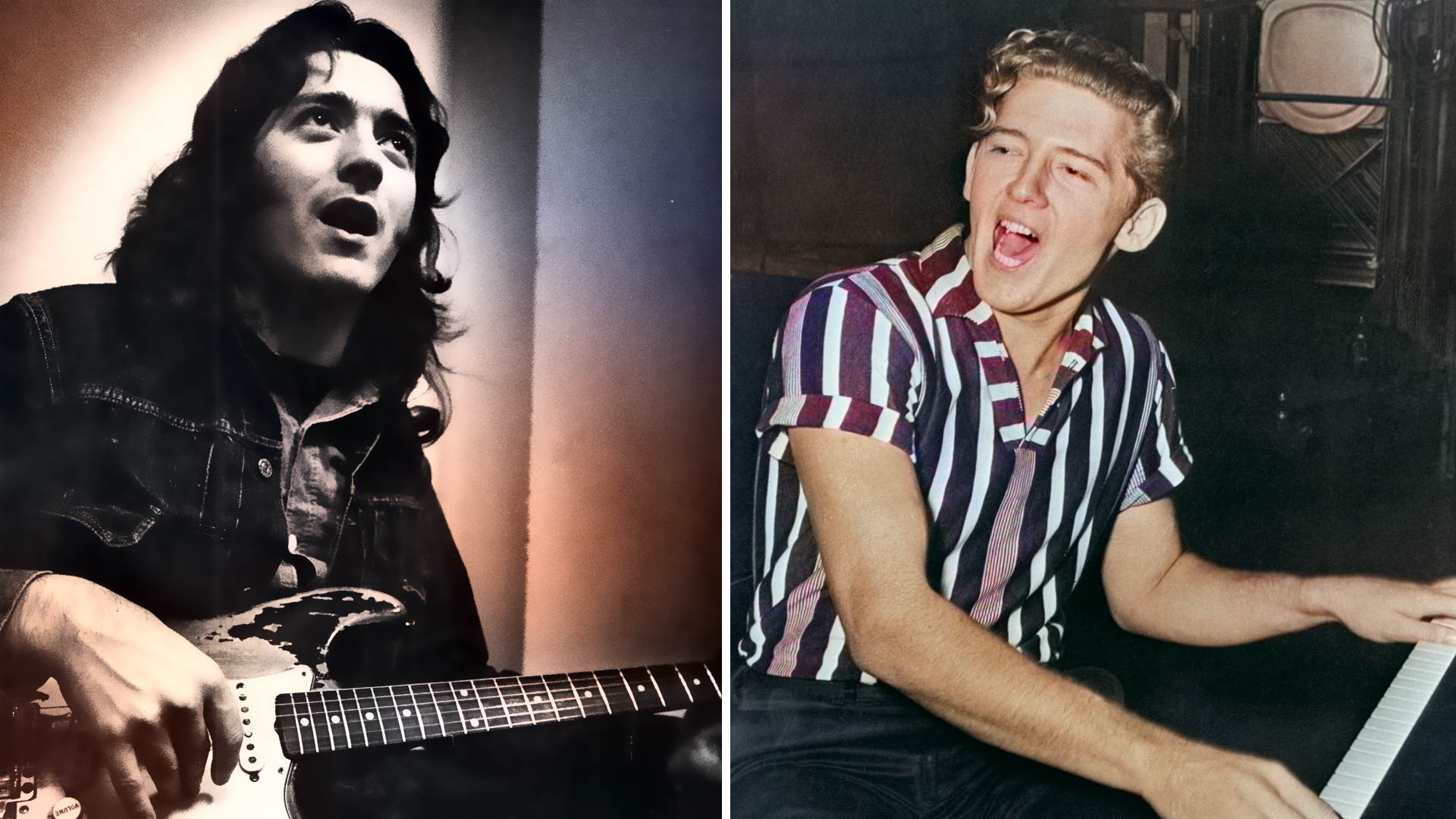

That one was interesting. Peter Frampton’s playing on the track had a certain pentatonic blues foundation. Now, I love Frampton. His live album with Humble Pie is one of my all-time favorites. But when I listened to what he did with the song, it got me thinking about how New York isn’t really about the blues anymore. It’s more multicultural, and there’s a definite Asian and Middle Eastern thing going on. You walk down the street on a Saturday night, and you see this new wave of immigrants, and you hear sirens going by.

I wanted to reflect that change with what I did. I wanted police sirens to come out of the guitar. I told Mario, “Put up that song and let me see what happens.” I figured out where the harmony was, and I just stretched it. I soloed through the whole song and tried different things, and I reacted to what was going on. When the song ended, Mario looked at me and said, “Well, that one’s done then.” [laughs]

Bowie’s big acoustic guitar sound that was featured on the remix of “Time Will Crawl” is still way up in this new version.

That was David’s thing at the time – an Ovation Adamas through a [Scholz] Rockman into a Fender Twin. You notice how gloriously ratty the acoustic is, which is exactly the same tone you hear on the first Tin Machine record. That was his sound for that album, which also points to the fact that, in lots of ways, it was a transitional record.

David felt things on the one and three, and I kind of sat more in the two and four, so we had a little push-pull thing going on.

Reeves Gabrels

You added quite a lot of guitar to “Zeroes.” Toward the end, it’s a veritable guitar symphony.

Yeah, I built that up in the end. That song kind of took me by surprise. It was the first track that I worked on at Electric Lady. Mario and I listened to it, and we figured out what sounded really good and what could be different. The first thing we did was strengthen the acoustic guitar. We miked up my Breedlove acoustic, and I got the headphones on, and I realized that I had the same separation in my head that I used to have with David. His guitar would be in one ear, and my guitar would be in the other.

We used to cut acoustic guitars together like that. Often he’d play 12-string, and we would sit facing each other – two mics, headphones on. David felt things on the one and three, and I kind of sat more in the two and four, so we had a little push-pull thing going on. He would move his shoulders a certain way. He would look at me, but it was like he wasn’t there – he was somewhere else. He would cross his legs and one of his feet would bounce. I would take cues from his body language.

Anyway, at Electric Lady, I played the track with my eyes closed, and I would see him. But then when the track was done, I opened my eyes and he wasn’t there. [sighs] I was glad that I was in the live room all by myself. I had about 30 seconds to wipe the tears away before anybody came in. [pauses] It wasn’t always like that. Most of the time, it was like when we were working together, meaning he wasn’t always in the studio. He would say things like, “I’ll see you Friday. You know what to do.”

What was your guitar and gear setup for the sessions?

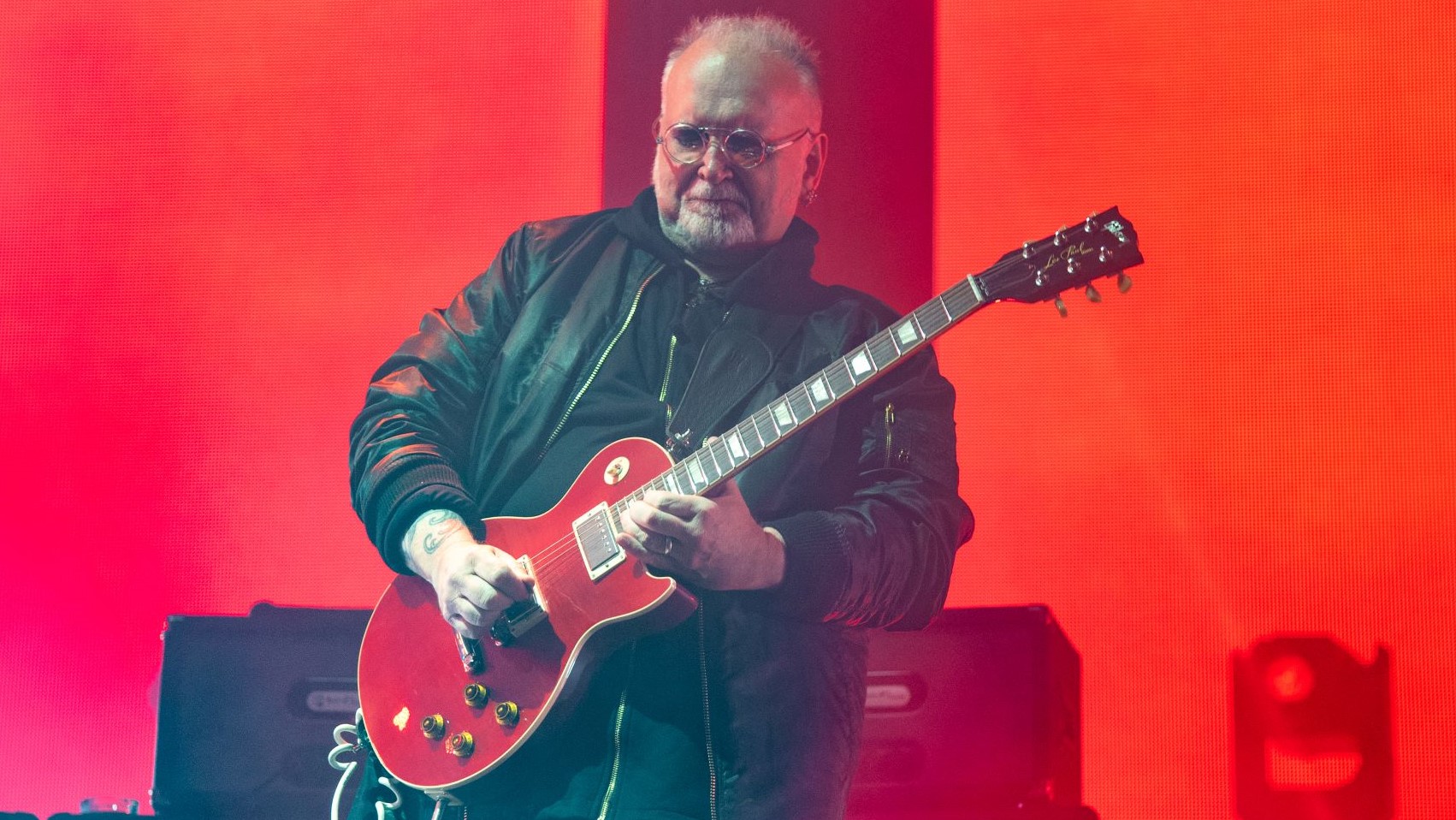

I have three signature models with Reverend, so I brought what I consider to be my “desert island” guitar, the Spacehawk. It works so well in most any situation but particularly when I’m playing at high volumes. I also had my original RG model, which has a Sustainiac in it, and a Trussart Steelcaster. During the sessions, I bought an R7 Les Paul, which ended up on “Beat of Your Drum.” So it was those four electrics and the Breedlove acoustic.

I’m always hesitant to discuss non-tube amps, but I really like the Yamaha THR100H [modeling amp], and I’ve found that I can use it in a number of ways. And it weighs about 10 pounds, which is always handy. I ran one side of it like it was a Fender Deluxe, and the other side like it was a Hiwatt.

My effects chain was basically what I use live with my band, the Imaginary Friends: an Ibanez Weeping Demon Wah, a Source Audio Multiwave Distortion, a modified Boss GE-7 EQ, an MXR Phase 90, an SIB Varidrive, a Line 6 M9, and then a Barefoot Pale Green Compressor and a Meris Ottobit Jr. pedal. Oh, and there was also the Alexander Syntax Error and a Korg Kaoss Pad. That’s it for pedals on the floor, but I also used the Line 6 Helix for recording direct.

David never identified himself as a guitarist, but he was quite good. For him, the guitar was a tool.

Reeves Gabrels

You mentioned cutting acoustic guitars with David before. Nobody really talks about him as a guitarist. What kind of player was he?

David never identified himself as a guitarist, but he was quite good. For him, the guitar was a tool. I always liked for him to track an acoustic rhythm part, because he had a certain feel and a lope to his playing. When you see old pictures of him as David Jones the folk singer, or when he did “Space Oddity,” he was a 12-string guy. He’s one of the few people I ever knew who could tune a 12-string. [laughs]

Barre chords weren’t his thing. When you think about the chord voicings on “Space Oddity,” where he’s playing a sliding E form but he’s letting the open E and B strings ring out, that’s a byproduct of discomfort with playing barre chords. But it became a stylistic thing that worked for him.

David always picked such distinctive guitarists to work with. Did he ever tell you what he liked about your playing and why he chose you?

This is interesting. I met David during his Glass Spider tour. My ex-wife, Sara, was doing press for the tour, so I hung around backstage a lot and talked to him. He didn’t even know I played guitar, and I never told him. He just thought that I knew a lot about music and art. But Sara gave him a tape of my band, and he listened to it. So one day I’m at home and he called me. I thought it was a practical joke, and I said, “All right, who the fuck is this?” And he goes, “It’s David. Sara gave me the tape, and you sound like the guy I’ve been looking for. Why didn’t you tell me you play guitar?”

So I flew to Switzerland and went right to the studio with him. The first thing we did was work on the remake of “Look Back in Anger.” He said, “I need you to do stuff on the beginning and end, and then play guitar through the song.” And I said, “Well, what are you thinking?” And he goes, “This should be like German gothic cathedrals.” And I said, “All right…”

So I guess that was my audition with him. I went to stay at his house in Switzerland. I ended up being there for a month, but I remember at the end of the first week, I said, “Why am I here?” Because it wasn’t really clear what we were doing. And he laughed and said, “Basically, I need somebody that can do a combination of Beck, Hendrix, Belew and Fripp, with a little Stevie Ray Vaughan and Albert King thrown in. Then, when I’m not singing, you take the ball and do something with it, and when you hand the ball back to me, it might not even be the same ball.”

And you were like, “I can do that.”

More or less. [laughs] That was the start of it.

Buy David Bowie: Loving the Alien (1983–1988) here.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.