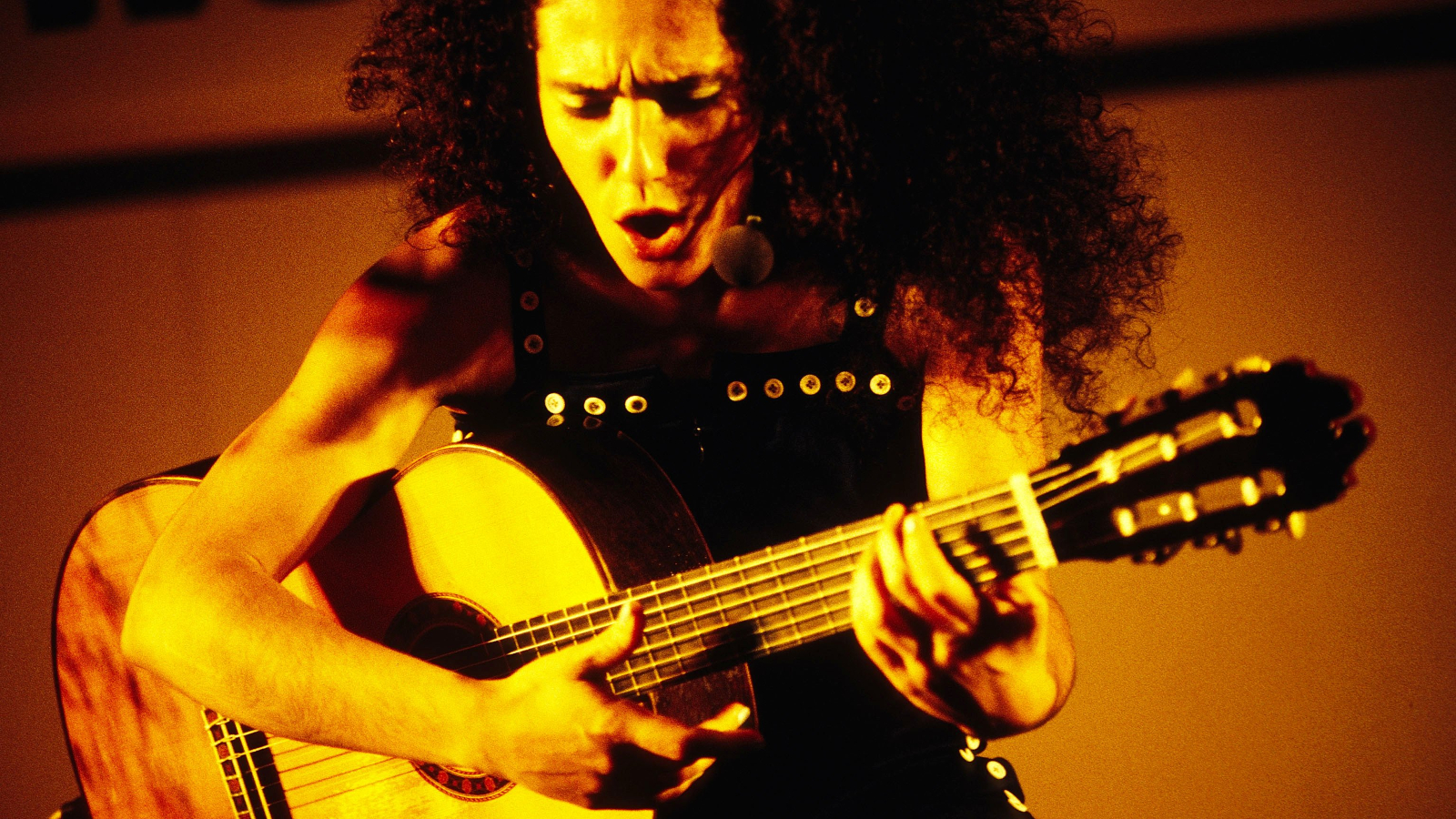

Badi Assad is the younger sister of renowned Brazilian guitarists Sérgio and Odair Assad. She came out of the highly competitive world of classical guitar but soon went in her own musical direction, searching for something more.

When she was just 17 years old, Assad was named Best Brazilian Guitarist at the International Villa Lobos Festival. Soon after, she began to experiment by adding mouth percussion and rhythmic body percussion to her performances.

In 1995, her solo album Rhythms won Guitar Player’s readers’ poll for Best Classical Album of the Year, and she was voted Best Acoustic Fingerstyle Guitarist by the magazine’s editors.

Even though Assad has roots in the classical world, her music defies categorization. It’s purely Badi.

You’ve been playing guitar since the age of 14. Did you start because of your father and brothers?

It was a vehicle to be closer to my father, to feel more a part of the family. It was also a sentimental issue why I started playing the guitar, and luckily, I also had the ability for it, like my brothers.

Do your brothers compose?

My brother Sérgio is the one who composes, and Odair is the one who plays all those notes that Sérgio writes. They make a very good balance. I’m not an improviser on the guitar. It’s not my school. I came from a classical background, where practicing is mostly done alone.

Nowadays, my approach to it is completely different. I don’t have to prove anymore to myself that I am a good player

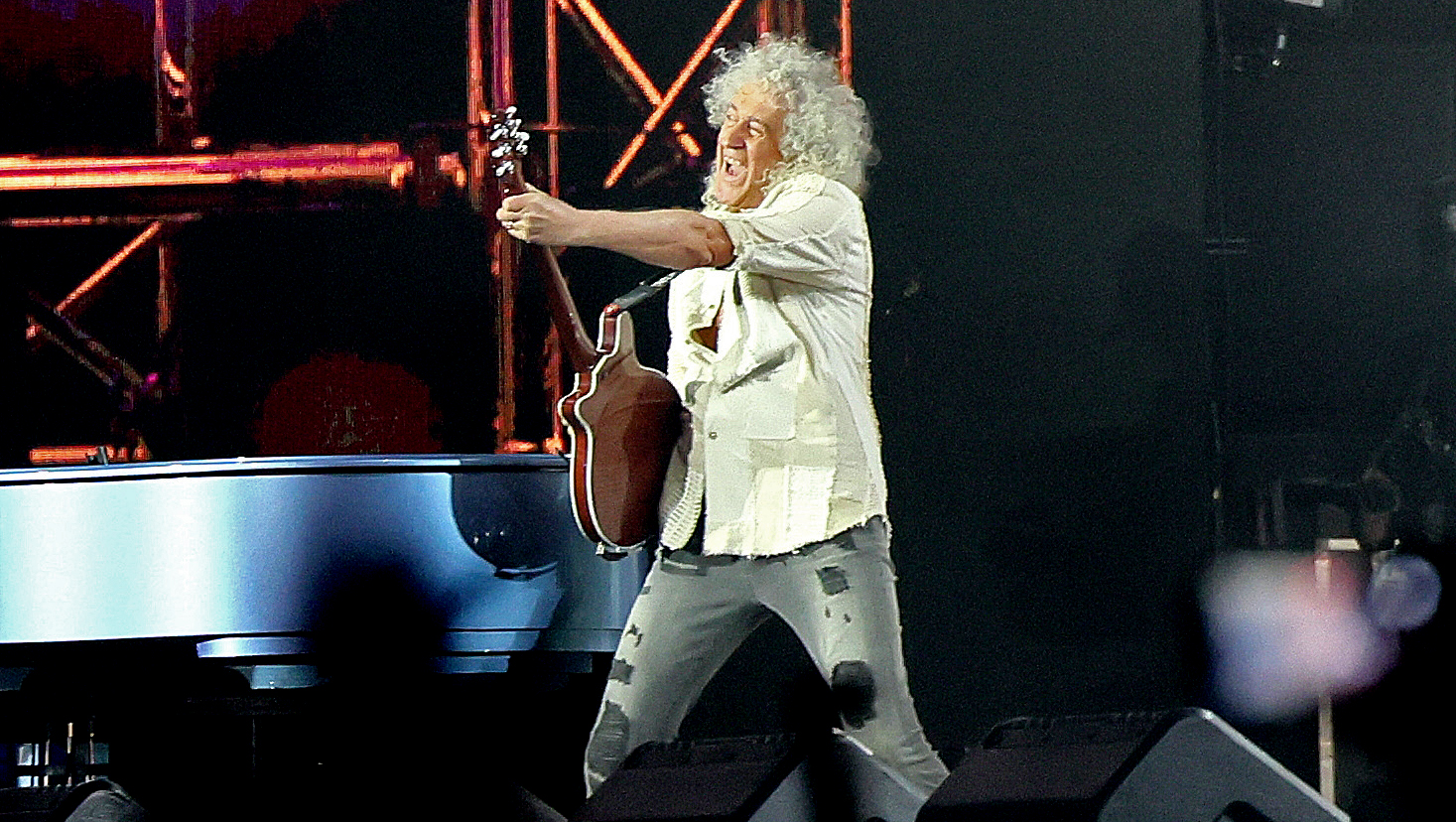

Badi Assad

I never had a lot of interaction on the guitar or playing with friends. I would practice for hours and hours a day, studying and going for competitions and all that, until one day I realized this wasn’t for me.

When I started singing and doing the mouth percussion, my idea was always to do as much as I could alone. So on my first album, which is solo, they started calling me a “one-woman band,” because when you hear it you have the impression that more than one person is performing.

You wrote in your bio that guitar wasn’t just an instrument to you. You said, “It represented my ties to Brazil, my ties to my father, my ties to non-independence, and my ties to the past.” How did you reconcile that with your self-identity?

My way of dealing with it was totally spiritual. Badi is not just a guitar player; Badi is everything. Guitar is just a part of who I am.

Nowadays, my approach to it is completely different. I don’t have to prove anymore to myself that I am a good player. And it’s not like my parents were going to love me less if I didn’t play. When I do music now, guitar is just a part of it.

I don’t feel the need to do all this complicated stuff. I just play. If it’s complicated, it’s okay. If it’s not, it’s okay. Before, everything had to be complicated. So I freed myself to play simple stuff and find the beauty in that.

Were you trying to transcend what your brothers were doing?

When I started playing the guitar, I totally wanted to be like them. They were my mirror. I was more like a little boy than a little girl. I liked to climb trees, and my father would relate to me like a boy, because he didn’t know how to have a girl.

My father’s just really macho. But when I started singing, my feminine side came out. Even my posture with the guitar became more feminine. I never played on my left leg like most classical guitarists; I always played on the right leg.

It’s not like you go and search and you copy somebody. It’s just waking up that makes you alive in other areas. I am always awake for the little things that can happen or appear. You never know where.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

"Get off the stage!" The time Carlos Santana picked a fight with Kiss bassist Gene Simmons and caused one of the guitar world's strangest feuds

“It’s a special kind of moment when you hit that first note of a solo and you literally get nothing.” He’s played with David Bowie and the Cure, but Reeves Gabrels says things don’t always go right, even for the pros