How Nels Cline Mixed Notes and Noise – to Great Effect – on 'Share the Wealth'

Cline explains how an expanded Nels Cline Singers lineup inspired him in the search for fresh sounds.

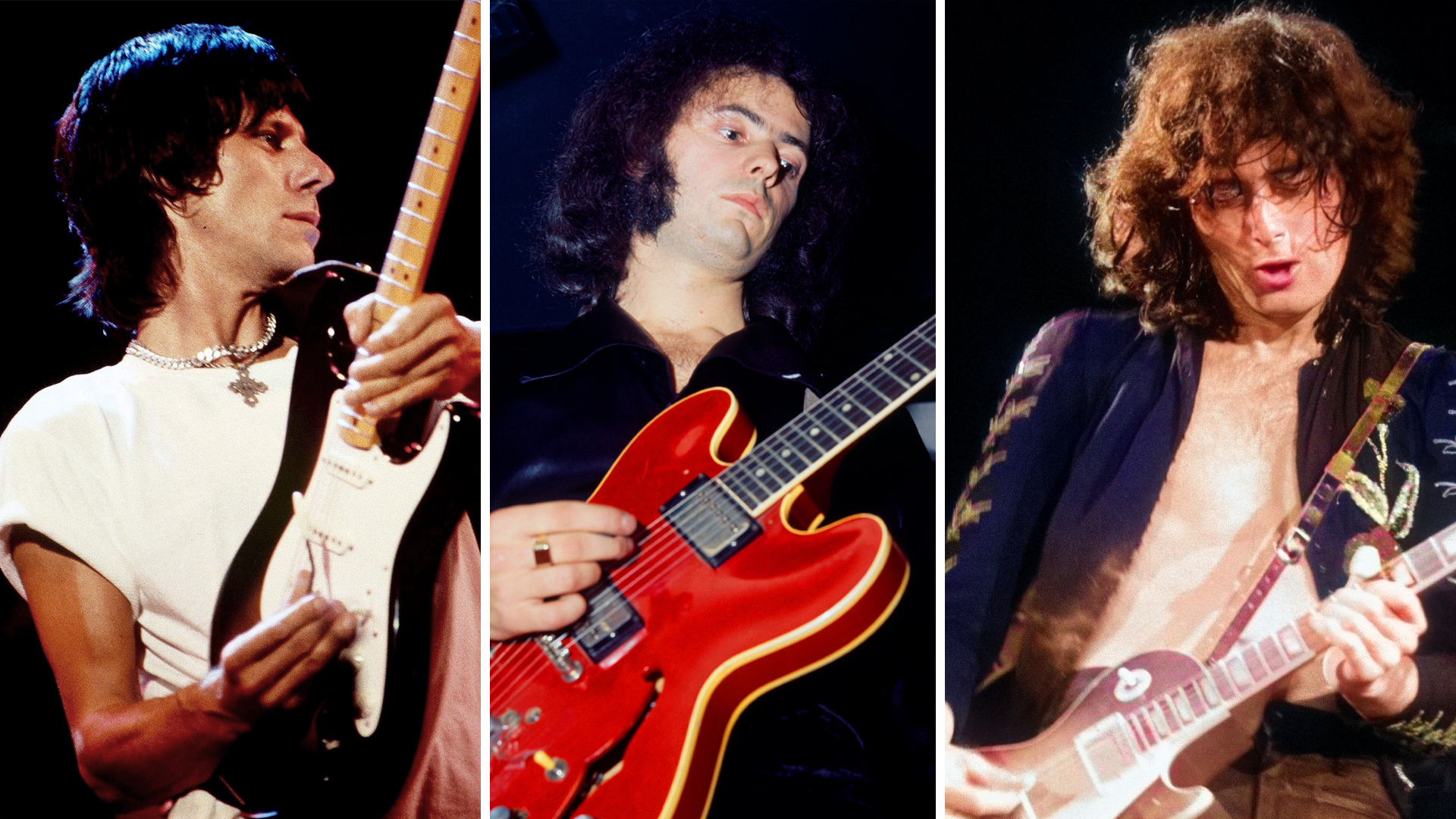

Nels Cline is one of those rare musicians who traverses the worlds of jazz, pop, and the avant garde while retaining a unique personal voice throughout the journey. In the guitar world, only Bill Frisell and Marc Ribot come quickly to mind as fellow travelers.

Cline is equally at home and equally himself whether playing rock-god guitar solos on his Fender Jazzmaster at pop festivals with Wilco, wielding his Gibson Barney Kessel on theater stages in duo with Julian Lage, or assaying lap steel with Mike Baggetta in the tiny back room of a Brooklyn bar.

Share the Wealth (Blue Note), the latest record with his instrumental band, the ironically named Nels Cline Singers, manages to incorporate elements from each of the guitarist’s many musical worlds.

The one cover tune, “Segunda,” by Caetano Veloso, features him trading searing solos with saxophone and keys. Elsewhere, he creates the kind of soundscapes at which he is equally adept, while his acoustic side is represented on some sensitive tunes, stemming from personal loss.

In this version of the Singers, Cline is joined by drummer Scott Amendola, Skerik on tenor saxophone, bassist Trevor Dunn, Brian Marsella on keys, and Cyro Baptista on percussion and vocals.

All, save Baptista, are adding electronic textures to the tunes, until it is impossible at some points to discern who is doing what. Yet somehow the mélange of sound never descends into mere noise and remains remarkably musical throughout. We discussed the evolution of this particular aggregation.

“The expanded Singers were going to be called the Nels Cline Singers Unlimited, but I couldn’t because there’s already the group Singers Unlimited,” Cline explains. “They did a record with Oscar Peterson in the ’70s. It also would have been yet another confusing name for my discography.”

In addition, we talked about the challenges of a guitarist working with a keyboard player and, of course, the challenges faced by all under the cloud of Covid-19.

I’ve known Skerik for something like 18 years, but didn’t play with him until last year. It turned out to be this remarkable experience, not only because of his use of effects pedals but also because of the directness he brought

What distinguishes a Nels Cline Singers project from a Nels Cline solo project, or a Nels Cline 4?

I never thought about marketing when I came up with these monikers. The Singers was initially my second trio, and we have been going for almost 20 years now.

The original Singers were drummer Scott Amendola and, for about 10 years, bassist Devin Hoff. Then Trevor Dunn came onboard. It is generally an electric project, although there’s acoustic material on every record. It has been my main project for all this time.

Cyro brings so much of the colorful energy Brazilian music infused into American culture in the ’60s and ’70s

The group has moved beyond a trio on this record.

The Singers first expanded when I asked Cyro Baptista to play percussion with us. I was becoming increasingly dissatisfied with being the main treble clef voice all of the time. I’d been desiring more flavor, and Cyro brings so much of the colorful energy Brazilian music infused into American culture in the ’60s and ’70s.

When Michel Levasseur asked me to do an expanded version of the Singers for the Victoriaville Festival, I added Brian Marsella on keyboards, who is on the new record; Zeena Parkins, on electric harp; and Marc Ribot on guitar. We only did one gig, but it planted the idea of expanding the band.

How did Skerik come onboard?

I’ve known Skerik for something like 18 years, but didn’t play with him until last year. It turned out to be this remarkable experience, not only because of his use of effects pedals but also because of the directness he brought to bear on his playing. I started thinking about him with the Singers, and then Scott said, “Skerik’s been listening to your music for years.” I asked him to play, and he was enthusiastic about coming out.

How did the album come together?

We recorded for a couple of days in Brooklyn at this place called the Bunker. To this day, the band has never played a gig in this configuration. It was a studio experiment. Nothing was particularly thought out, except for the ballads, “Nightstand” and “Passed Down,” which helped me come to terms with an old friend’s suicide.

But they don’t feature the whole band. The music I brought in was pretty sketchy, but we developed a lot of material in two days. The next thing I knew, I had this sprawling, yet satisfying recording. I gave it to Blue Note president Don Was and he said, “Let’s do this.”

Any guitarist playing with a keyboard player is dealing with chord-voicing issues, but you both produce electronic sounds so it would appear to double the challenges. How did playing with keyboards affect what you play?

It’s interesting you ask that question, because the first time I heard Brian, he was playing solo and he was all over the place in this amazing way. He has technique but also a respect for and expertise in using Farfisa organ or melodica – instruments that aren’t the usual Fender Rhodes, Wurlitzer, B-3, and acoustic piano. I love what he does with the Farfisa, because I’m a big fan of that sound.

In his playing, I hear his respect for popular music from all over the world. We managed to successfully merge Brian’s sensibilities and my own in a way that eschews standard soloing.

On the single, “Beam/Spiral,” there’s no guitar solo. What one hears is largely me and Brian looping on the fly and doing various electronic things. Scott Amendola was also generating sounds, using his pedalboard to process his drums, which, like Skerik’s effects, could be used in the mix or not.

You do solo on the opener, “Segunda.”

It’s like an introduction to the orchestra. I had to push myself to play more guitar because I’m more comfortable these days playing chords, or doing some looping and non-guitar-sounding treatments.

The electronic sounds you four make blend really well. It could easily have turned into noise, but you each found your space. Did you record live?

It’s primarily live. One of my plans was to generate a whole lot of rhythmic material that was completely improvised, and then collage tidbits of it into some psychedelic madness, inspired by ’70s Brazilian Tropicália music, as well as my roots in psychedelic rock and fusion.

To that end, I would set up clicks in our headphones with Eli Cruz, who engineered and co-produced the record, and we would just start playing. On one tune, Scott forgot to turn his click on, so he was playing something completely different. We all just turned the click down in our mixers and soldiered on for almost half an hour. That became “Stump the Panel.”

I had no intention of having an almost 18-minute track on this record, but I was amazed by how the improvisations were going

I had no intention of having an almost 18-minute track on this record, but I was amazed by how the improvisations were going. I liked them better than my tunes. Three improvisations are edited. I did some strategic muting here and there to make it a good, repeated listening experience.

Were there any overdubs?

On “Beam/Spiral,” when it gets to the pounding eighth-note section – you can find pounding eighth-note sections somewhere on every Singers’ record – I overdubbed as it builds to flesh out the strumming and make it fuller. I added this guitar I also use on “Passed Down.”

I like layered guitars, and I particularly like doubling just to get the little bit of natural chorusing and a little extra shimmer, or an extra overtone, resonant, slightly out-of-tune sound

It’s a late-’50s Danelectro Convertible – the hollow one with the hole. I did some strumming on that. On both tunes, I miked the guitar acoustically and blended it with the pickup. On “Beam/Spiral,” I also overdubbed a doubled melody with distortion just to give it a little sweeter sound.

I’m glad you brought up the rhythmic strumming, because I was going to ask how you know when it’s reached the maximum tension point. Is it a mental thing or is it physical?

Wow! There’s a question I’ve never been asked. It’s certainly intuitive, so it might be more emotional. I live for sustained, hypnotic tension and honoring an overtone signature – just getting inside the sound. I associate it with Sonic Youth and My Bloody Valentine. But it’s more dynamic, soft to loud, as opposed to My Bloody Valentine, which is loud and louder.

With the addition of keyboard, it’s sometimes harder to tell which pads are coming from you and what are keyboard sounds. On “Nightstand,” are you using a freeze-type effect?

That’s the Gamechanger Audio Plus Pedal. Those lovely Latvian gentlemen gave me one, and it’s remarkable. I used it also on a section of “Ashcan Treasure” that I inserted later. I wrote some thematic material just because I wanted to hear my Dobro with Brian on toy piano. I thought it needed an unexpected twist, so I played a solo with the Plus Pedal. You can use it without the dry guitar sound – just the sustain.

You basically painted the tune from the palette of sounds you put together.

Yeah. I wasn’t trying to honor the idea of a jazz session, like, “This is what we played in the studio and that’s that.” I like layered guitars, and I particularly like doubling just to get the little bit of natural chorusing and a little extra shimmer, or an extra overtone, resonant, slightly out-of-tune sound.

The way you were describing “Stump the Panel,” it sounds like it was improvised, but there is a unison part you and Skerik play together.

Yeah. I just jumped on it. Also, on the end of “Stump the Panel,” Brian starts this spooky, two-chord electric piano thing, and Skerik does this fuzz-octave heavy-metal riff. I answered with blasts of detuned whammy pedal and Fuzz Factory noise, while Trevor jumped in with some fuzz, commenting on that.

On “A Place on the Moon,” I came in with this Bm6 chord, and you hear Skerik immediately hit this matching arpeggio. It was completely unplanned and not an edit. This cool chemistry was happening.

It comes through on the record. Do you remember what distortion you used for that unison line you play with him?

It was very likely the Goo, my signature distortion pedal. ToneConcept made 250, and all 250 sold. It’s very creamy and potentially loud, based on a vintage Marshall Guv’nor distortion pedal, but with more gain and fewer knobs.

Were you using a vibrato at the end of that tune?

I’m sure I was somewhere, because I’m always using my old Boss Vibrato. I use it with Wilco all the time. It’s maybe a bit of a crutch at this point, but I love it.

What kind of acoustic guitar is at the beginning of “Ashcan Treasure?”

It’s an old Dobro. That’s a magical guitar. It’s from either the late ’20s or early ’30s. It was restored to playable glory by Tom Crandall at TR Crandall Guitars. Tom completely recreated the fingerboard, because there was almost no wood left.

It belonged to someone named Curtis Rogers, who wrote his name Curtis R on the fingerboard. It’s bedazzled and has a faded painting on the body, under the strings, which apparently is of his wife.

The patina is extremely distressed. It’s a most vibey guitar. It still has the jute string on it that Rogers used as his strap. Tom and I were just talking about the guitar the other day. We don’t know how the biscuit on that guitar never went flabby, because it’s old and was obviously played to death. I’m obsessed with resonator guitars. I’m ashamed to admit how many I have. But this one is absolutely unique sounding and mellow.

The ’59 Jazzmaster is on anything that needed that single-coil edge

What other guitars did you use?

I used the Danelectro convertible, the Dobro, and my ’59 sunburst Jazzmaster with the anodized aluminum pickguard. The ’59 Jazzmaster is on anything that needed that single-coil edge.

I also have a John Woodland, a.k.a. Woody, Jazzmaster that I use quite a bit. It was put together years ago from a vintage body, a kit neck, a vintage tremolo, and a Mastery bridge. It has two Seymour Duncan PAFs disguised as Jazzmaster pickups, because people don’t like 60-cycle hum in New York City.

It’s on “Beam/Spiral” and might also be on “A Place on the Moon.” I tend to use it when I know I’m going to use a lot of compressor and clean guitar sounds, so that the compressor doesn’t bring up all the 60-cycle hum.

What amp were you using?

A Studious Moseley. Studious is a small company in Chicago. It’s the same amp I use with Wilco. The Wilco one is a 2x12 piggyback, and this one’s a 1x12 combo. I like amps without too much personality and not too much treble.

The Studious has the low mids I crave, and it’s simple: volume, treble, and bass. It’s my main gig amp here in New York, unless I need something loud and small. Then I use the ZT Club, which is solid-state, Chinese, ugly, and quite versatile. For the added part on “Ashcan Treasure” I used a Studious Selye.

All his amps are named after scientists. It has an aromatic cedar cabinet, so I can stow my sweaters in there during summer months.

You seem to like a fair amount of clean headroom.

You are absolutely right. I don’t need too much volume anymore. For years, with Wilco, I was playing that 40-watt Tim Schroeder head with four 12s. That sounded like God, but it was too much.

Do you have plans for any musical projects that you’re going to be able to do in the current circumstances?

Yuka Honda and I will be doing a live stream at the end of this month for some paying listeners. I play solo, and then we’ll do our duo, CUP. We’re going to keep the CUP thing going, because, after all, we are living in the same house and have musical equipment there. [Honda and Cline are a married couple.]

There are very few people in our Covid bubble at this point. But one is our good friend Sean Lennon, so I was able to do a Yoko Ono song as a benefit for Hudson Valley Votes and Common Cause – I also played drums – with Sean, Charlotte Kemp Muhl, keyboardist Joao Nogueira, and Yuka.

We did a T. Rex cover for James Corden. We are all in the same neighborhood, away from the city, so I can jam with them. The main thrust of my work has been composing for my Brooklyn-based Consentrik Quartet, with Tom Rainey on drums, Chris Lightcap on acoustic bass, and Ingrid Laubrock on saxophone. I’ve written a suite of about nine pieces and two pieces dangling on their own.

I don’t know when I’m going to be able to get together with them and work out the material, but I got a grant through Ars Nova in Philadelphia. I’m conspiring with Eli Crews to go to his house outside of Kingston [New York], where he has a studio. We’ll all get tested, put Ingrid in one of those Flaming Lips bubbles, record this material and see what happens.

- The Nels Cline Singers' new album, Share the Wealth, is out now via Blue Note.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“He used to send me to my room to practice my vibrato.” His father is the late Irish blues guitar great Gary Moore. But Jack Moore is cutting his own path with a Les Paul in his hands

"Why can't we have more Django Reinhardts going, 'F*** everybody. I'll turn up when I feel like turning up'?" Happy birthday to Ritchie Blackmore. The guitar legend looks back on his career in an interview from our December 1996 issue