“His Storytelling Was as Brilliant as His Guitar Playing”: How the Spirit of Skip James is Felt Stronger than Ever Today in Bentonia Blues

Washed up at age 30, the legendary bluesman was rediscovered in 1964, just five years before his death.

A year before Bob Dylan went electric with a sunburst Fender Stratocaster at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, a bluesman who hadn’t recorded and had rarely performed since the 1930s stunned the festival’s crowd of 15,000 spectators with an electrifying performance of his own.

Just weeks earlier, Nehemiah Curtis “Skip” James had been recovering from cancer treatments in a Tunica, Mississippi hospital when John Fahey and two friends tracked down the 61-year-old legend and persuaded him to play again.

His re-emergence came during the 1960s blues revival at a time that also saw the “rediscovery” of Bukka White, Son House, Mississippi Fred McDowell, Mississippi John Hurt and others, who played to new audiences and scored record deals.

Armed only with an acoustic guitar and a microphone, Skip James captivated the Newport audience with his high falsetto and spidery fingerpicking that often commanded all 10 of his fingers.

“Skip at Newport ’64 was just transcendent. It was incredible,” recalls Dick Waterman, who witnessed the performance and later managed James’ career until his death in 1969.

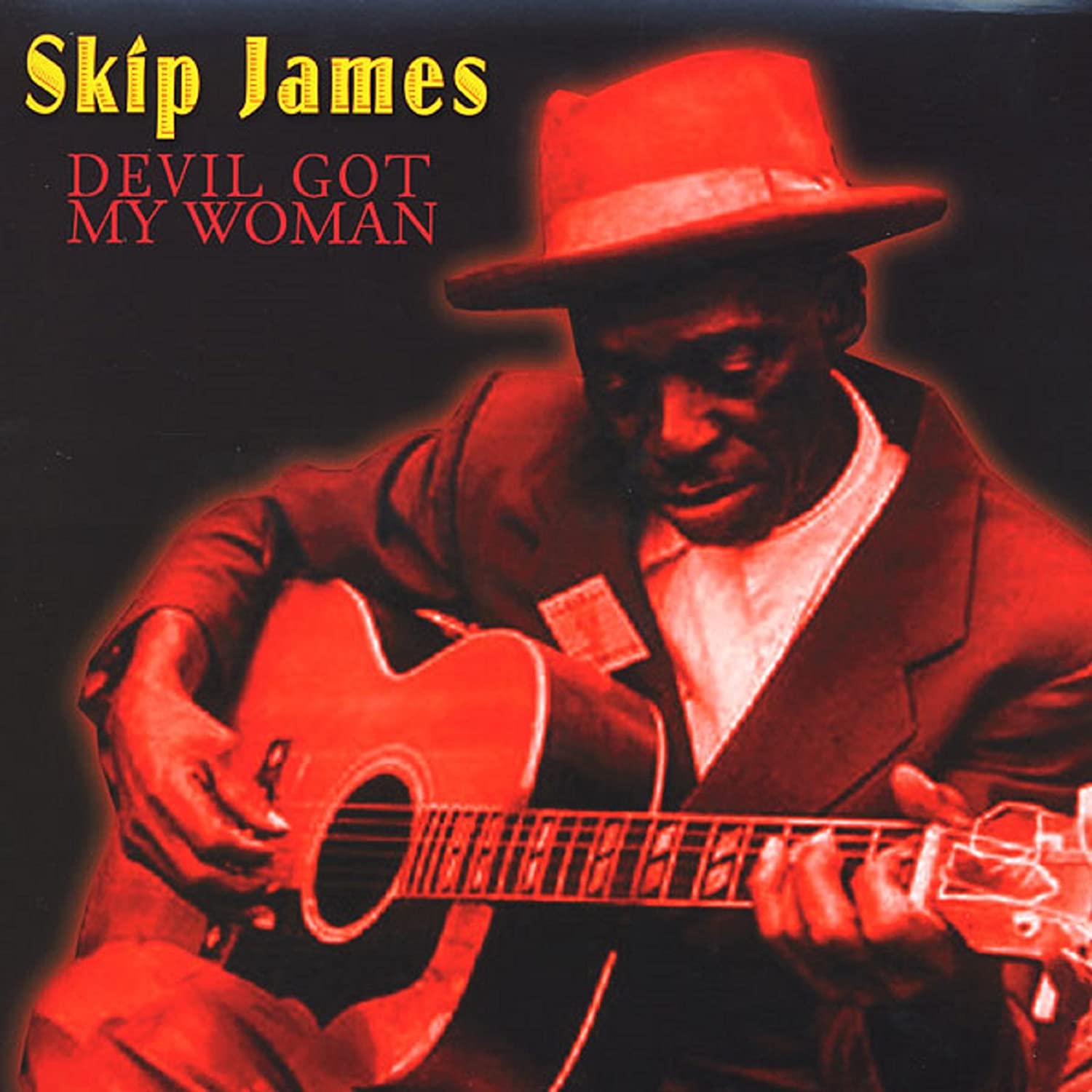

“He sat down and he set his fingers down on the fretboard, and he took a breath and hit the first note of ‘Devil Got My Woman,’ and it was just incredible. Just shivers even at the memory of it.”

Skip at Newport ’64 was just transcendent. It was incredible

Dick Waterman

It’s safe to say no one else at Newport was playing blues guitar the way James did at the time – not House and not White, who were also on the bill in 1964.

Instead of the more commonly used open-G and open-E major-key tunings, James played in a D-minor tuning, which lent songs like “Hard Time Killing Floor” and “Cypress Grove” an ominous tone. The tuning was so particular that it became associated with Bentonia, Mississippi, James’ hometown, through a succession of players.

“In other regional styles of Delta blues, you may have an open-tuned guitar where the minor gets introduced against the major chord,” says Ryan Lee Crosby, a Massachusetts-based blues artist who learned Bentonia blues from Jimmy “Duck” Holmes, the last living musical link to James.

“But in the Bentonia style, it’s a minor chord, where major notes get added on top, so the tension between the major and minor is inverted.”

This differentiator sets up the darker, minor-key sound of Bentonia standards, but there are also other structural differences – or, rather, a lack of structure, as there are no choruses and few turnarounds in Bentonia blues, and no set number of times to repeat a pattern.

The droning, hypnotic tones come from ringing the open strings with the thumb or forefinger while fingerpicking, and frailing across the strings with the others.

While James doesn’t have the household-name recognition of B.B. King, Muddy Waters or Robert Johnson, his influence has never been stronger among blues and folk musicians. The Carolina Chocolate Drops, a folk collective that launched the careers of Rhiannon Giddens, Dom Flemons and Leyla McCalla, carries his penchant for freeform, minor-key romps.

Emerging blues guitarists and singers like Buffalo Nichols and Adia Victoria wear his influence even more prominently.

“I came into Skip James’ music at the perfect time in my life,” says Victoria, who discovered him around the time she got her first guitar, at age 21.

“I felt spoken to in a way that I’d never felt spoken to. I felt reached and seen. And I felt like, through Skip James, I became more in touch and aware of my culture as a Black southerner, in a way that I hadn’t been before.”

I felt like, through Skip James, I became more in touch and aware of my culture as a Black southerner

Adia Victoria

James’ 1960s revival didn’t last long. Before his cancer roared out of remission in 1967, his handlers squandered the considerable buzz he had created at Newport. By the time Waterman helped him get a record contract in late 1965, more palatable blues artists like Hurt were getting more attention, gigs and money.

It didn’t help that James, by all accounts, was a proud man who felt his playing was of higher artistic merit than his contemporaries on the folk blues scene.

“He was a very different, difficult, contrary kind of person,” Waterman says. “In other words, Skip had a huge ego and he loved to be flattered, and the best way to get along with Skip was to be flattering and tell him how great he was.

"He felt he himself was performing at a much, much higher level, which may or may not be true, depending on how you look at it. He definitely was not ‘one of the guys.’”

[Skip James] felt he himself was performing at a much, much higher level, which may or may not be true, depending on how you look at it

Dick Waterman

Bentonia, Mississippi, sits atop the hills that rise above the vast alluvial Delta, where blues music evolved at sharecropper plantations and juke joints, makeshift venues where laborers could find music and moonshine.

Like many former farming outposts across the South, Bentonia is bisected by a railroad whose trains don’t bother stopping anymore. The only thing riding these rails are freighters headed north and south on the same tracks that dropped Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf in Chicago.

The Blue Front Café, considered the oldest juke operating in Mississippi, still stands next to the tracks in the center of town. Behind the cinderblock façade and barred front doors, locals mosey in to buy cigarettes and sundries, lingering sometimes to talk to the proprietor, Jimmy “Duck” Holmes.

At 74, Holmes is not only an elder statesman – he’s also the last of the Bentonia bluesmen.

The walls of the Blue Front are covered with faded posters and snapshots of the Bentonia Blues Festival, which Holmes has run for five decades. Music equipment is everywhere – microphone stands at half mast, guitars mounted onto the cinderblock and shiplap walls, a pair of dusty Peavey guitar amps on the floor under a pile of cables.

On a folding card table, copies of his eighth album, the Grammy-nominated Cypress Grove (Easy Eye Sound, 2019), are stacked for sale. Holmes recorded the collection of potent and haunted performances from the Bentonia canon – the title track, “Hard Times” and “Devil Got My Woman” were part of the original 26 sides James recorded for Paramount Records for $40 in 1931 – with the Black Keys at Dan Auerbach’s studio in Nashville.

“There’s an urgency with getting any of these types of people in the studio, older musicians that are sort of one of a kind,” Auerbach says. “The whole thing just felt like a blessing, really, just to be able to get to do it. And to share the love of the music and live in Jimmy’s world for a little bit.”

The whole thing just felt like a blessing, really, just to be able to get to do it

Dan Auerbach

Holmes didn’t learn the Bentonia blues from James, who played the Blue Front occasionally. James and another Bentonia artist, Jack Owens, both learned from a man named Henry Stuckey, who lived in the area and, for a time, on the Holmes farm.

Stuckey allegedly learned the open D-minor tuning from a group of Bahamian soldiers he met in France during World War I and brought it home. Owens began to teach Holmes off and on beginning in the late ’70s, and by the ’90s the pair were playing daily at the Blue Front.

“I picked up some licks from him, which I was doing all along, but he was a hard act to follow,” Holmes says.

“He wanted me to learn it, and I think now, from a divine perspective, he wanted me to learn it but he didn’t know how to teach it. He would come every day and say, ‘Boy, let’s play. You’ve got to learn to do this.’”

[Skip James] wanted me to learn it, and I think now, from a divine perspective, he wanted me to learn it but he didn’t know how to teach it

Jimmy “Duck” Holmes

Over the past few years, Holmes has taken on the role of instructor to younger players who visit him at the Blue Front. Robert Connelly Farr, a Mississippi native who lives in Vancouver, B.C., reinterprets his lessons into thunderous back-alley blues, while Mike Munson’s adaptations are fully absorbed into his singer-songwriter compositions. Ghalia Volt, who honed her one-woman-band craft while busking in Brussels, Belgium, frequently shows up to perform at the juke.

Neither Victoria nor Nichols have made a similar pilgrimage to Bentonia, but James’ influence is a strong undercurrent in both artists’ music. On A Southern Gothic (Warner Bros.), Victoria’s third album, the Bentonia sound manifests in the eerie tension, tuning and fingerpicking on songs like “Magnolia Blues” and “Carolina Bound.”

“That D-minor tuning lends itself to some of the more melancholic aspects of human emotion, and combining that tuning with his voice, that falsetto, was very plaintive, mournful, but it could also sound manic, as well,” Victoria says.

“His style of singing is what my internal voice sounded like. You can hear that weariness. You can hear that wisdom and that defiance, as well. It’s like a combination of dark and light that really spoke to me – that startled me, really.”

His style of singing is what my internal voice sounded like

Adia Victoria

Nichols discovered James on a blues compilation when he was 12 or 13, he says, but didn’t seek out a full James collection for another five years. As a metalhead at the time, Nichols was already familiar with drop-D tuning, so transitioning to open D-minor tuning wasn’t too much of a stretch.

He eventually left behind his shredding for the organic tones of an acoustic guitar and a country-folk blues sound. For Nichols, the most enduring influence of James on his own playing isn’t what he played as much as his individualism.

“Whenever he would play songs that weren’t his, he would always make sure to play in his own style,” Nichols says. “That’s always stuck with me, because I’ve never really been the type to learn other people’s music. The two or three Skip James songs that I play are the two or three that I know. This music to me is supposed to be individual and be about the expression of the player.”

True to his word, on his cover on the James composition “Sick Bed Blues” from his 2021 self-titled debut album (Fat Possum), Nichols speeds up the tempo and improvises on the original licks with his own slide-accented descending figure.

Such improvisation is a central feature of the Bentonia sound. Holmes maintains that the songs are impossible to transcribe because they’re never played the same way twice. That’s due in part to playing from the heart, he says, but also because guys like Owens were uneducated.

I had to unlearn a lot of the sort of technical precision and rely more on the feeling of it

Buffalo Nichols

“If you told Jack Owens, ‘I want you to do four counts of ‘Hard Times,’ he wouldn’t know what you’re talking about,” Holmes says. “‘Uh, can you run me an E chord?’ Have no idea what you’re talking about. Even though he could do it, but he was unaware he was doin’ it.”

Adds Nichols, “You hear the way he plays, and the biggest challenge is you can’t really sit down and transcribe it because it’s not very predictable.

"The way he’s going to play, it all relates to the way he sings, and if you hear him do three recordings of the same song, it’s always going to be a little different. I had to unlearn a lot of the sort of technical precision and rely more on the feeling of it.”

Victoria agrees that playing the music riff-for-riff is missing the point. James understood how to use the guitar to serve his purpose of telling honest stories. Emulating him or anyone else takes the heart out of the music.

“Skip James’ music is an invitation to use your imagination to press forward in what he did,” she says. “He’s already done that. He’s mastered that, so there’s no point in trying to replicate it.

If the story is good, the guitar should serve you

Adia Victoria

"But I think that he still serves a valuable lesson of how can you give sound to your mood and your world, and how can you swathe your storytelling in this oral blanket.

“And to stay out of your way,” she adds. “If the story is good, the guitar should serve you. The guitar should never be a crutch behind a lack of insight in your story. I think that was the brilliance of Skip James. His storytelling was as brilliant as his guitar playing, and vice versa.”

Browse the Skip James catalog here.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Jim Beaugez has written about music for Rolling Stone, Smithsonian, Guitar World, Guitar Player and many other publications. He created My Life in Five Riffs, a multimedia documentary series for Guitar Player that traces contemporary artists back to their sources of inspiration, and previously spent a decade in the musical instruments industry.

“He used to send me to my room to practice my vibrato.” His father is the late Irish blues guitar great Gary Moore. But Jack Moore is cutting his own path with a Les Paul in his hands

"Why can't we have more Django Reinhardts going, 'F*** everybody. I'll turn up when I feel like turning up'?" Happy birthday to Ritchie Blackmore. The guitar legend looks back on his career in an interview from our December 1996 issue