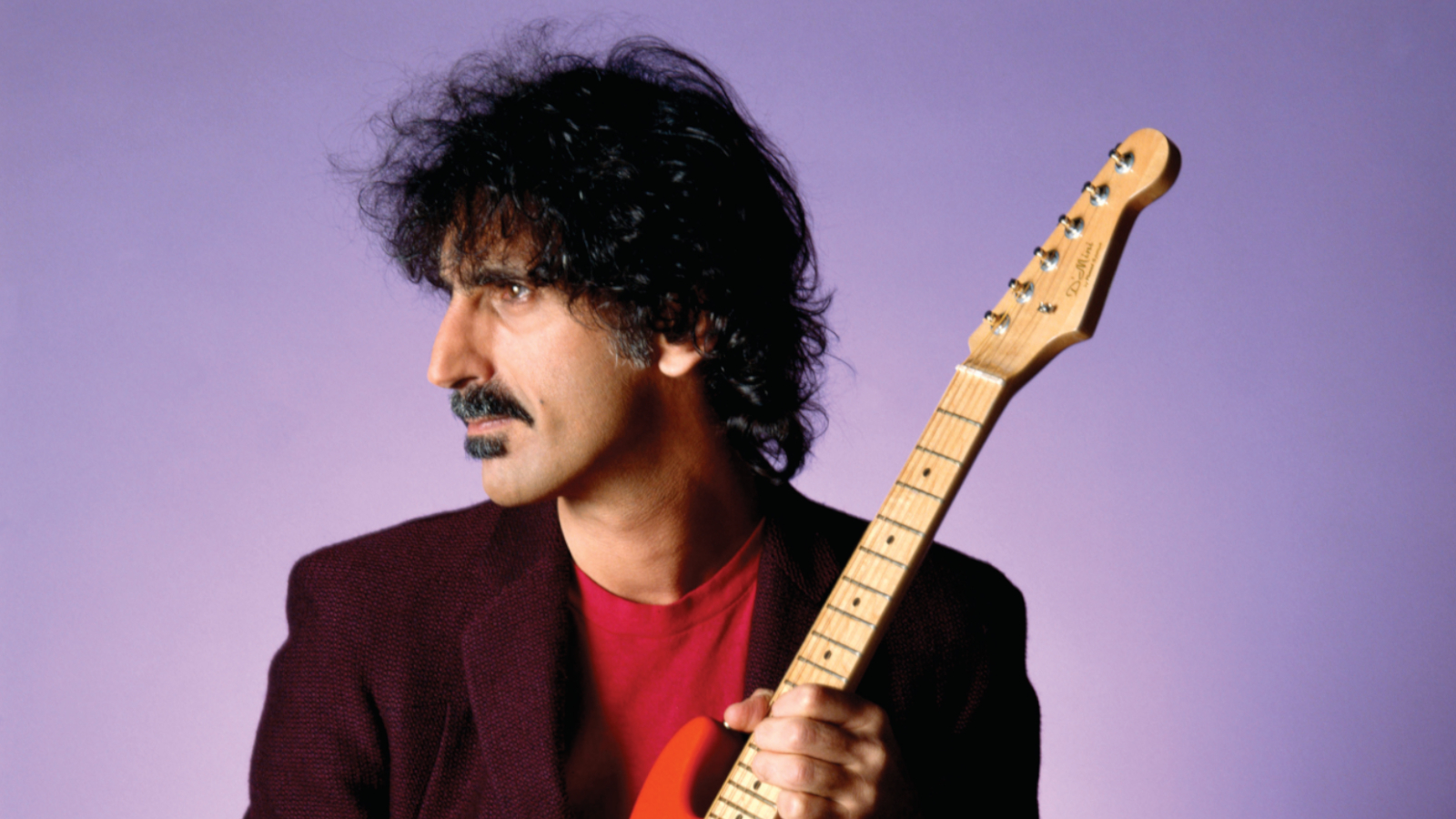

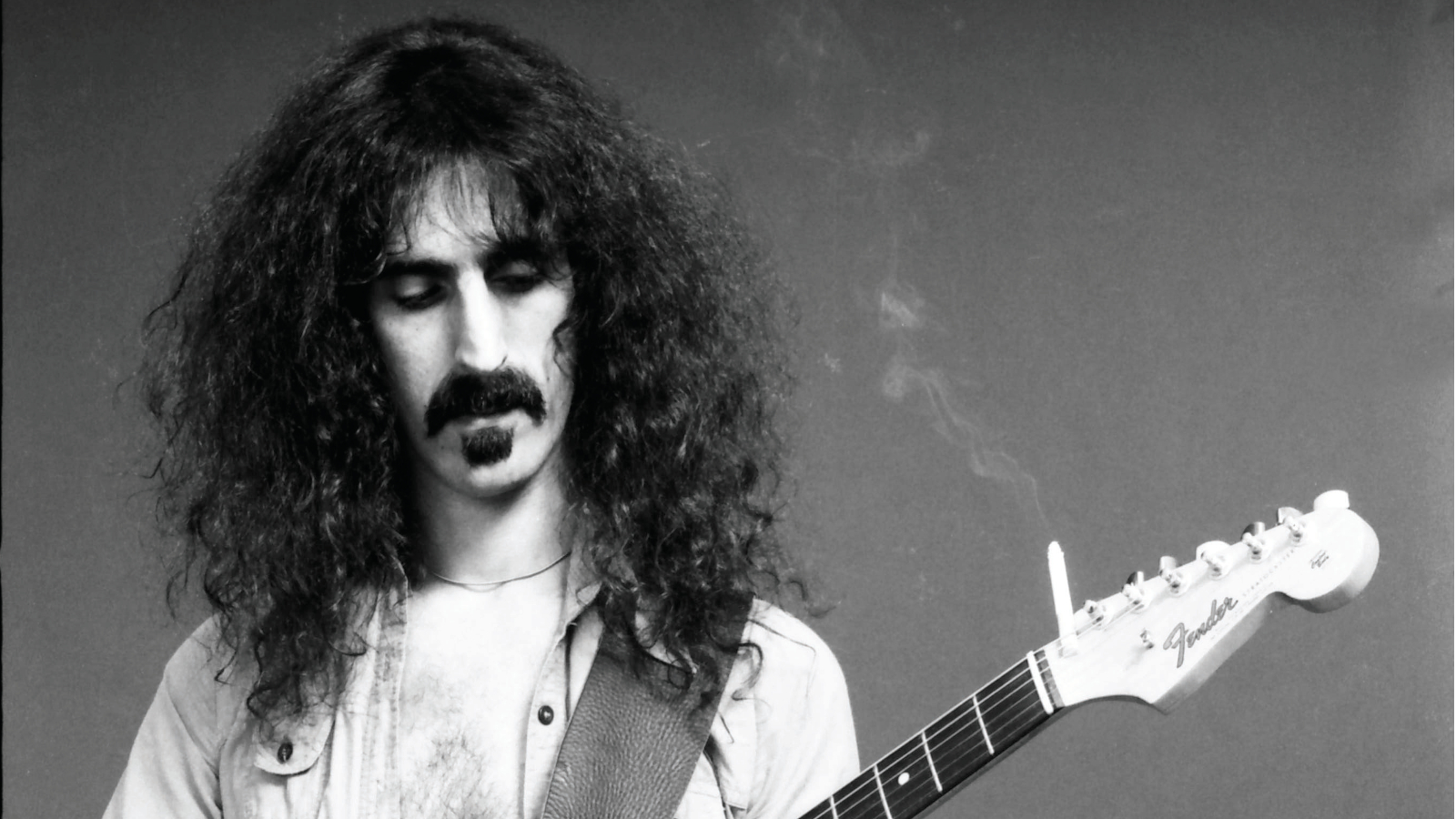

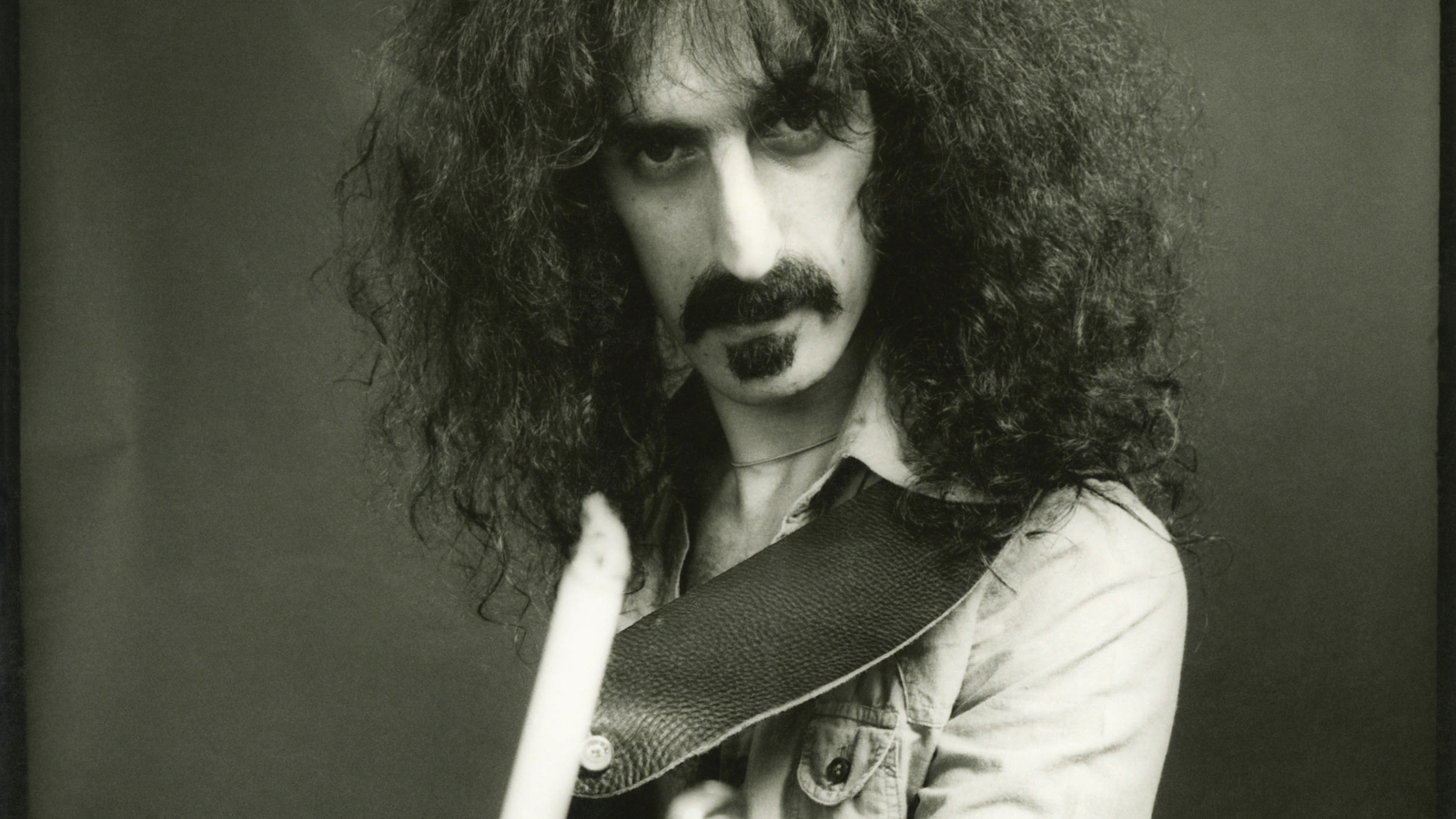

“He Will Eventually Be Remembered as One of the Great Composers of Our Time”: Adrian Belew, Don Preston, Mike Keneally and Jon Anderson Remember Frank Zappa

The musical method behind the perceived madness of a “genius” guitarist

On the Mothers of Invention’s 1969 Uncle Meat, you can hear Frank Zappa exhort keyboardist Don Preston to climb up to the Royal Albert Hall’s majestic pipe organ and belt out the riff to “Louie Louie.” Now 90, Preston was part of the all-star tribute band the Grandmothers of Invention, a touring group of alumni from various eras of the Mothers’ life.

“Musicians, guitarists mostly, often come up to me and ask, ‘How do I play like Zappa?’” Preston explains. “I say, ‘It’s simple – just listen to all the music Zappa listened to!’”

Like most teenagers growing up in California in the ’50s, Zappa loved doo-wop, R&B, blues and early rock and roll. But his adolescent musical imagination was truly set alight by Ionisations, a piece of percussive avant-garde music by French-born composer Edgard Varèse.

This gave him a taste for 20th-century modernist composers, from Charles Ives to Igor Stravinsky.

“He’d listen to that stuff like other kids were listening to the latest rhythm and blues song,” Preston remembers. “That music, the complexity of it, matched the complexity of his own mind. In the opening phrase of [Stravinsky’s] Petrushka, the flute is in 5/8 and the orchestra is in 2/4. On ‘Little House I Used To Live In’ on our Burnt Weeny Sandwich album [1970], the bass and drums are playing in 11/8 and the melody is in 12/8.

“One of the things that made him a genius was that he could play experimental music and get it over to the audience by throwing in doo-wop or pop music. He’d use real popular music to play real unpopular music.”

If there’s one thing that unifies the extraordinarily pluralist catalog Zappa created over his lifetime, it is this combination of “popular” and “unpopular” music. From the Mothers of Invention’s 1966 debut, Freak Out!, to landmark titles like Hot Rats, Apostrophe (’) and Zappa’s best seller, Sheik Yerbouti, he would create a progressive musical universe where every style – from rock to reggae, from surf-rock to Schoenbergian serialism, from free jazz to musique concrète – was up for grabs.

“When you’re adopting or adapting a style in order to tell a story,” the late composer once said, “everything’s fair game. You have to have the right setting to the lyric. The important thing at that point is to tell the story.”

When you’re adopting or adapting a style in order to tell a story, everything’s fair game

Frank Zappa

His lyrics also reflected his complexity. Drawing on sex, deviance, politics and social concerns, Zappa would satirize, parody and mock pretty much everyone. His absurdist universe was populated by fake hippies, charlatan gurus, corrupt politicians, dental-floss farmers, dumb groupies and dumber rock stars.

If his overarching quest was a search for truth, he did it by exposing and taking the piss out of its opposite. Jon Anderson contends that progressive music began with Zappa. “It was a combination of things,” the founding vocalist for the prog-rock group Yes contends.

“If you listen to Zappa, the Beatles, Vanilla Fudge, Buffalo Springfield, and Charles Mingus and Roland Kirk, there was such a plethora of interesting music around the mid ’60s, and that all inspired me when Yes started to do long-form music. His music was really meticulously put together, and he was a comedian at the same time.”

Freak Out!’s blend of chart-friendly tunes (“You Didn’t Try to Call Me”), outré psych-rock (“Who Are the Brain Police?”), experimental jazz (“The Return of the Son of Monster Magnet”) and social commentary (“Trouble Every Day”) pointed the way.

He was reading the zeitgeist nicely and expressing attitudes that a lot of people felt

Mike Keneally

Keyboardist/guitarist Mike Keneally played in Zappa’s band for his last-ever tour, in 1988, but was still a child when he first heard Freak Out! “Half of it is easy to get hold of, the other is absurdism,” Keneally says. “Frank was combining things in different ways.

“He was reading the zeitgeist nicely and expressing attitudes that a lot of people felt. It was surprising to see an artist who was of the scene but also apart from it, and commenting on it so acidly.”

The Mothers borrowed from the Beatles’ Sgt Pepper’s cover for 1968’s We’re Only In It for the Money, ridiculing the prevailing hippie scene on the hilarious “Who Needs the Peace Corps?”

“That album is Frank’s greatest and most sustained piece of social commentary, and a startling musical and technical achievement,” Keneally says “But he was using naughty words too, and there were sped-up voices!”

With its advanced multitracking and production techniques, 1969’s Hot Rats became a jazz-fusion landmark and contained one of the composer’s best-known works, the opening track, “Peaches En Regalia.”

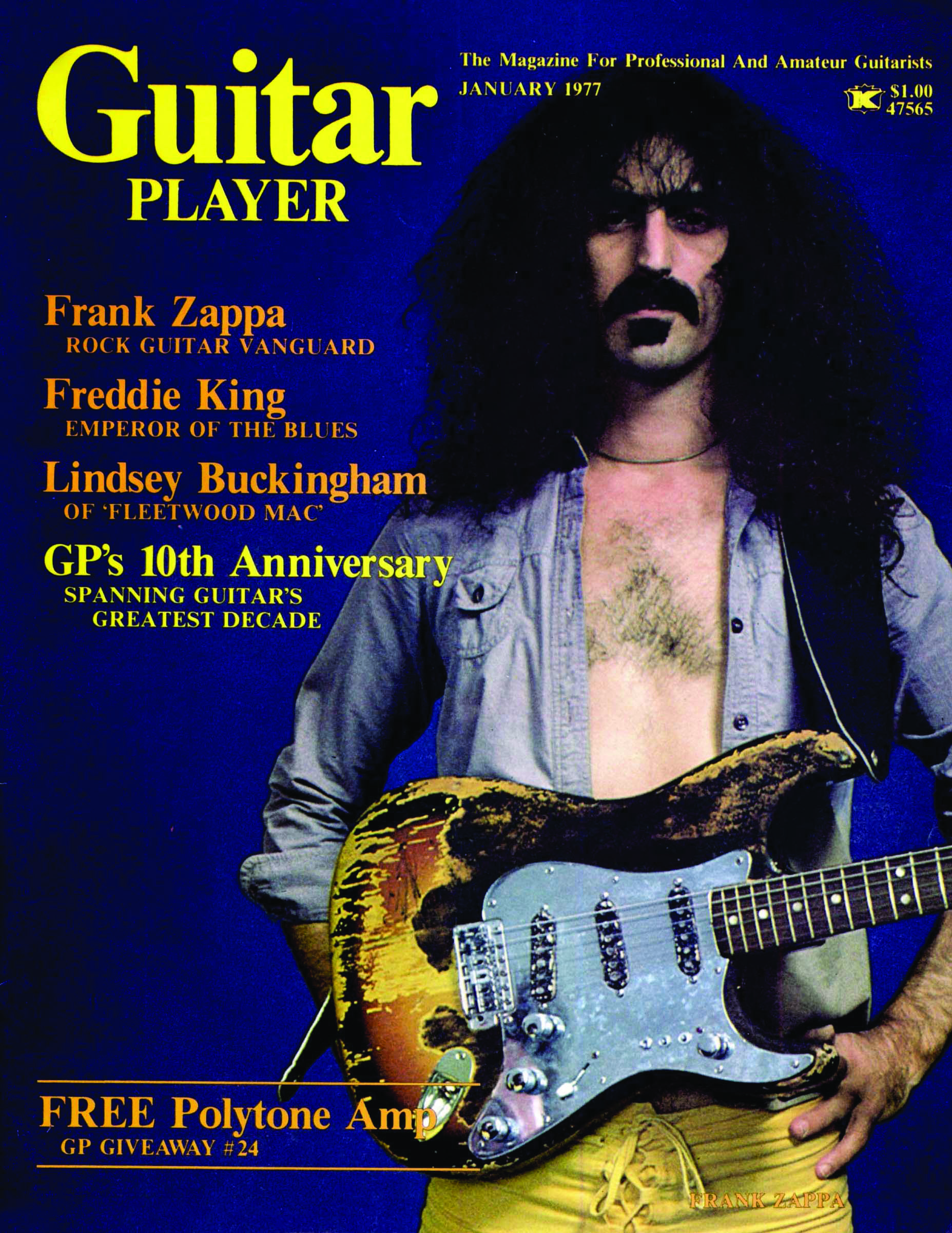

Zappa disbanded the first Mothers lineup that year, and over the next decade his sound benefited from his evolving production smarts and growing reputation as a grandstanding, idiosyncratic guitar hero.

Over-Nite Sensation, Zappa and the Mothers’ 1973 release, features some of his best-known songs – “Camarillo Brillo,” “I’m the Slime” and the absurdist masterpiece “Montana.” Zappa’s own Apostrophe (’) from the following year proffered “Don’t Eat the Yellow Snow” and “Cosmik Debris.”

Both albums featured progressive orchestrations and virtuoso playing from drummer Aynsley Dunbar, keyboardist George Duke and violinist Jean-Luc Ponty, but they also showed Zappa’s increasing, censor-baiting fondness for bawdy, scatological lyrics.

She said, ‘Is it really true he’s got a song called ‘I Promise Not to Come In Your Mouth?’' I said, ‘Yes, Mom, that’s true.’ She didn’t go to the show

Adrian Belew

“Oh, he’d go for the jugular,” Anderson says. “A lot of time as a writer it’s difficult to say exactly what you’re thinking. I would use metaphors all the time, but Zappa didn’t give a damn. He just said what he thought.”

Zappa recruited newcomer guitarist Adrian Belew for the concerts that produced 1979’s Sheik Yerbouti. Belew recalls that the band had a show in Cincinnati, where his mother, a Sunday school teacher, was living. “She was so pleased for me, but I told her I didn’t want her to come to the show because of the things I’d be singing.

“She said something that shook me to the ground. She said, ‘Is it really true he’s got a song called ‘I Promise Not to Come In Your Mouth?’ I said, ‘Yes, Mom, that’s true.’ She didn’t go to the show.”

While accessible, Sheik Yerbouti tracks like “Broken Hearts Are for Assholes,” “Bobby Brown” and the disco-pastiche “Dancin’ Fool” feature knotty musical ideas. Yet the seemingly cold misanthropy of the lyrics might deter the fainthearted.

“I asked him about it once,” Belew says. “He said he just reflects the craziness around him. He’d see other people go nuts and then write about that. There’s a part of the audience for whom that is the appeal – that he’s really putting it out there with radical tunes like that.”

Zappa encouraged Belew to play in unusual time signatures. “Without that I don’t know how I’d have made it into King Crimson,” he says. “A lot of our stuff is based on polyrhythms and odd time signatures, me singing in one and playing in another. He taught me how to be a professional musician and drew out of me that I could play more complicated material. He challenged me.”

As for Zappa’s proggiest moments, Mike Keneally goes back to 1973’s One Size Fits All. “‘Inca Roads’ is the quintessential Zappa tune,” he offers. “The subject matter [aliens landing in Inca times] is cosmic, but it’s not social commentary, it’s not cynical or sexual, and the music’s a multipart suite that goes through endless time and key changes.

[Music] has more to do with the composer than with the style of the times or the school that might have generated the composer

Frank Zappa

“The sound of George Duke’s keyboards is very prog, and the playing on there is virtuosic and exciting. For people into Henry Cow or Canterbury, Uncle Meat is ground zero. I think it was a huge influence on Fred Frith and Chris Cutler. Burnt Weeny Sandwich too. For Frank, that’s almost pastoral. I can see Genesis fans getting into that.”

In a 1992 interview, The Simpsons creator and lifelong Zappa fan Matt Groening asked the composer if he thought music should make progress, if a composer should do things that hadn’t been done before.

Zappa argued that, rather than be progressive, it was more important that music should be personalized. Music, he said, “should be relevant to the person who writes the music. It has more to do with the composer than with the style of the times or the school that might have generated the composer.”

By that time, Zappa, in failing health, had come full circle, throwing himself into contemporary orchestral music with Civilization Phaze III, which would be released posthumously in October 1994. An ambitious work composed on the then-cutting-edge digital sampling system, the Synclavier, it was complex, socially charged and, yes, fearlessly personalized.

He will eventually be remembered as one of the great composers of our time

Adrian Belew

It would be the last artifact from a seemingly inexhaustible imagination that offered up more than 60 albums over nearly three decades.

“He will eventually be remembered as one of the great composers of our time,” Belew contends. “Civilization and The Yellow Shark [Ensemble Modern’s 1993 release of Zappa’s orchestral works] are beyond anything anyone else has done. His use of Synclavier to create a new universe of sounds was incredible. He had so many sides to him, and the orchestral stuff is my favorite part of Frank’s work.”

“He’s very well respected,” Anderson agrees. “I did some shows with [youth orchestra project] School of Rock, and they’d just come back from doing a Zappa festival in Germany. These 30 kids could play Zappa music at the drop of a hat.

“Young people dig what he did.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“We’d heard Jimi Hendrix, we'd heard the Who, but now we finally got to see these guys. And watching Jimi Hendrix burn his guitar….” Grace Slick on Hendrix at Monterey, Jefferson Airplane and the Spanish origins of “White Rabbit”

“I’m still playing but I’m covered in blood. Billy’s looking at me like, ‘Yeah! That’s punk rock!'” Steve Stevens on his all-time worst gig with Billy Idol — and the visit to Jimi Hendrix's grave that never happened