“He Always Said, ‘I Make Records so Other People Can Hear My Songwriting’”: Christine Lakeland Cale Looks Back on the Musical Genius of JJ Cale

In this insightful interview, the late, great tunesmith’s wife reveals the guitars and gear behind JJ Cale’s craft and sheds light on his unique relationship with Eric Clapton

***The following article appeared in the June 2019 issue of Guitar Player***

Although he is known to many for his tunes that other artists made famous, JJ Cale was a consummate guitarist and songwriter who wrote a huge number of songs during a career that spanned from the 1950s until his unexpected death on July 26, 2013.

John Weldon Cale started his career in the early 1960s as a sound engineer, but the key to his ultimate success was an unwavering devotion to songwriting. He realized early on that it gave him the best chance of making a living at music.

And it paid off big time.

“I had already given up on the business part of the record business and had moved back to Tulsa and gotten me a job playing with some friends of mine,” Cale said.

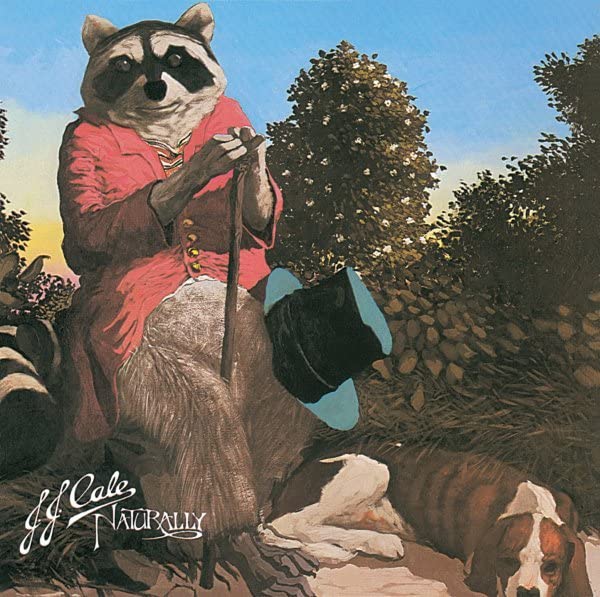

“When Eric [Clapton] cut ‘After Midnight,’ it opened up a bunch of doors, and I drove over to Nashville, and that’s when Naturally [Cale’s 1971 debut] was done.”

He went on to make another 15 albums, his last two being 2006’s The Road to Escondido and 2009’s Roll On.

Cale’s career was fast-tracked by Clapton’s recordings of “Cocaine,” “Travelin’ Light” and “I’ll Make Love to You Anytime,” and his fame was further bolstered by Lynyrd Skynyrd releasing “Call Me the Breeze” in 1975.

It’s gotta be Hendrix and JJ Cale who are the best electric guitar players

Neil Young

His songs always seemed ideal for interpretation, which helps explain the diverse cadre of artists that recorded or performed his tunes, including Johnny Cash, the Band, Chet Atkins, Freddie King, Santana, the Allman Brothers Band, Maria Muldaur, Captain Beefheart and, later, Widespread Panic and moe.

Although he also played bass, piano, pedal steel, banjo and flute, guitar was a centerpiece for Cale, and he had a style all his own. Call it the Tulsa Sound or whatever, but he had the knack for playing exactly what the song called for and making everything sound so easy and so right.

Said Neil Young, “Most of the songs and the riffs – the way he plays the fucking guitar is so great. And he doesn’t play very loud, either, and I really like that about him. He’s so sensitive. Of all the players I’ve ever heard, it’s gotta be Hendrix and JJ Cale who are the best electric guitar players.”

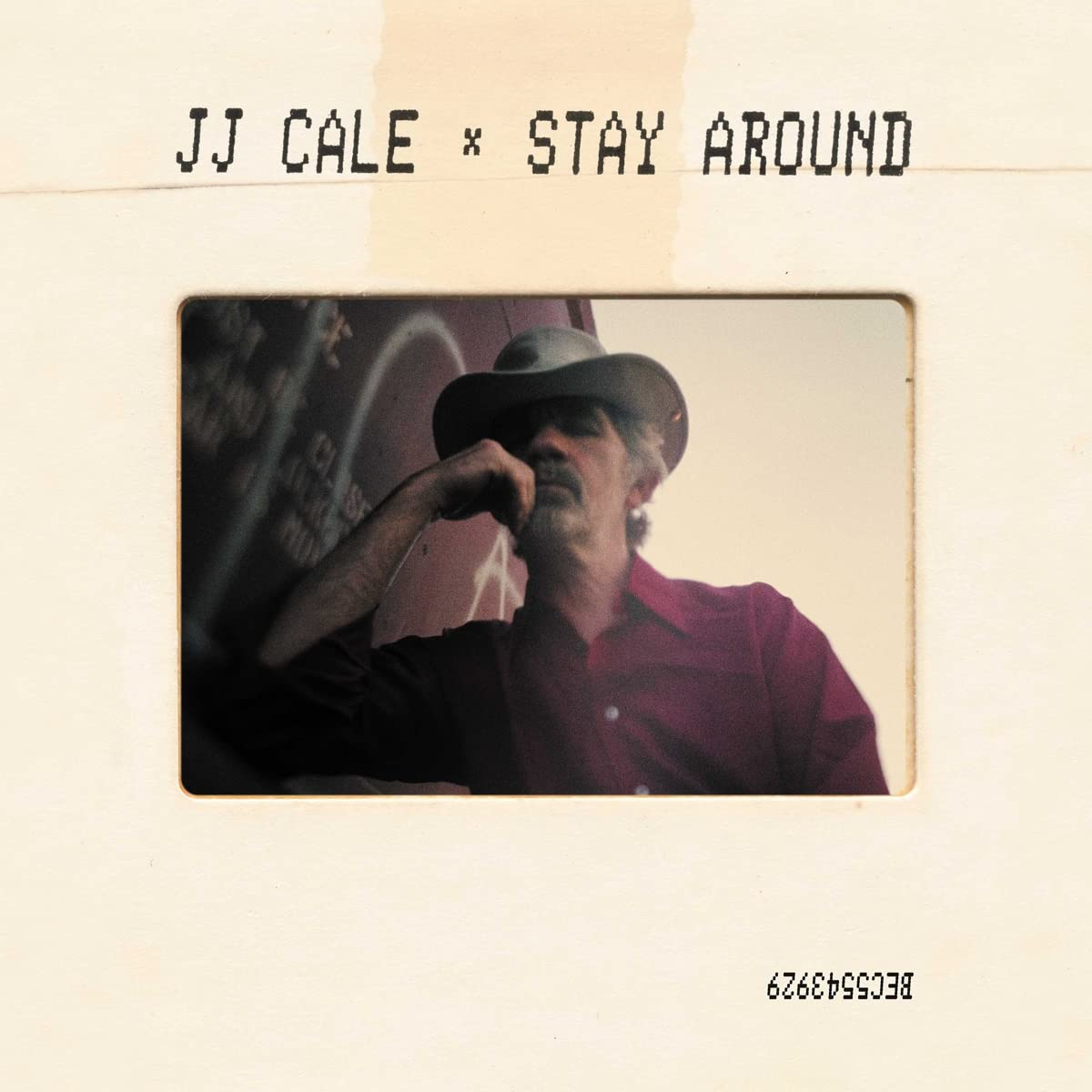

His posthumous album released in 2019 titled Stay Around (Because Music) presents 15 previously unreleased songs that were recorded, mixed and produced by Cale in his home studio, and which were chosen by his wife, Christine Lakeland Cale, and his friend and longtime manager, Mike Kappus.

On Stay Around, you can hear it in the tantalizing guitar arrangement on the title track, “Stay Around,” with its clean, plucky guitar and sweet slide parts; in the dobro and gritty guitar solo on “Chasing You;” in the bluesy resonator and slide tones on “Girl of Mine;” and on the banjo-driven “Wish You Were Here.”

In fact, Cale’s guitar tones and recording skills are in full bloom throughout these tracks, one of which, “My Baby Blues,” was penned by Christine Lakeland Cale, who spoke with GP about the record around the time of its release.

“That was actually the first song that John and I cut in the studio when we met in 1977,” Christine says. “I found it going through John’s musical bits and pieces, and it was an outtake. He cut his version of it in 1980, so it was one of those many outtakes over the years, where songs are cut and then not used on the next project.

["My Baby Blues"] was actually the first song that John and I cut in the studio when we met in 1977

Christine Lakeland Cale

“When I found that he had gone back and overdubbed and done some things to it, I thought, Oh, my goodness, he liked that song enough to fool around with it again. It kind of tied everything up in a bow and finished it, if you know what I mean.

“I was afraid it might be frowned upon, but I was encouraged by Mike Kappas, who had worked with John for decades. When I told him, it wasn’t written by John, he said, ‘That’s fine, you should put it on there.’

“So if people are going to think I’m being self-indulgent, I’ll own this one.”

How was it for you playing in the JJ Cale band?

I was scared when I started, because there was no rehearsal and it was just “wing it.” That was my early lesson. I wasn’t as experienced as the other players in his band were, but I was often replacing someone that had left. It was like, “I need to replace so and so… So you come on the gig.”

John was always very sure that everything would be fine. Over the years, I think he enjoyed the magic that happens when you’re just playing in the moment and everything is unpredictable.

I think he enjoyed the magic that happens when you’re just playing in the moment and everything is unpredictable

Christine Lakeland Cale

What guitars did John like most to play?

He was a lover of the guitar, and there are a lot of instruments that I intend to find new homes for, because there’s way more than I need. He had everything from a Ramírez classical to a Casio [PG-380] synth guitar.

He had a few Gibson acoustics and several Martins, including one that they made to his specs called the JJ Cale [a 000-45 created for Cale in 1991]. It’s on the cover of the album Guitar Man. He had Fenders and Gibsons, and he just liked to play everything. He would try several guitars on a song on a home demo.

He might record six different solos, and he would pick the one that fit the song the best, whether it was a fat-sounding guitar or something with an edgy rock tone. On one tour we did, a friend named Steve Ripley had made a deal with Kramer, and so for a while on that tour John played a Ripley Kramer [RSG-1].

And we did that with a stack of Marshalls. So that was a few weeks of a totally different sound, because it was the complete opposite of his folk/blues quiet side. It was more the power-rock side, and it was great fun. John was always curious and willing to try all kinds of things.

What did he play around the house?

He always played acoustic, but he loved to plug into amps, too. I think that was one of the things he loved about not having neighbors close by – because you can make noise and no one is going to complain.

Having lived in places where that does happen, he really appreciated being able to play freely at home.

When asked why he didn’t ever go into ProTools, his answer was he trusted his ears more than his eyes

Christine Lakeland Cale

What was his home studio like?

He had his own home setup, and he was very comfortable with it. When asked why he didn’t ever go into ProTools, his answer was he trusted his ears more than his eyes, and for him to start editing on a screen was too much of a stretch. He’d done it his way too long, and he was comfortable with his gear. He’d say, “I won’t be making music, I’ll be trying to learn all this new stuff.”

I think if he had been younger he would have embraced ProTools in a heartbeat. He just wanted to use what he was familiar with, so he was recording digitally on the obsolete Alesis HD24, which had a hot swappable hard drive. I had to go through all those hard drives to find out where he might have recorded bits and pieces of things.

What sort of outboard gear did he use?

He had some different preamps: a Langevin [Discrete Dual Microphone Preamplifier] and also a Sony preamp [possibly an MPX-3000] that we had for decades.

He liked certain things that allowed him to get there quickly so he didn’t lose the mood or the idea. He didn’t want to spend time fixing something. His gear was always set up so he could go right to it and record for an hour or two, or spend all day at it.

John was always an observer of life, even if he didn’t live it

Christine Lakeland Cale

What motivated him to write and record as much as he did?

He always said, “I make records so other people can hear my songwriting.” For him, it was okay that he didn’t think he was a great singer.

There were so many people that covered John’s material, and if they heard a demo of a song and then did it in their own way, that was exactly what John hoped would happen.

Do you recall how “Cocaine,” one of his biggest songs, came about?

John was always an observer of life, even if he didn’t live it. John didn’t do coke. He used to say something like, “I didn’t spend money on cocaine, but I made money on it because of the song.”

He observed what a hold it had on a lot of people, but other than recording a song about it, he wasn’t interested in it. He preferred smoking marijuana.

How did John like working with Eric Clapton?

They got along famously, and there was a lot of good energy when they were around one another. It didn’t happen super often, but the times when they were together, it was such an upper.

They had a mutual admiration society. John thought the world of Eric, and vice-versa

Christine Lakeland Cale

The music was always challenging because they were trying to deliver the knockout punch. But they had a mutual admiration society. John thought the world of Eric, and vice-versa.

I think John was comfortable in his own skin. He knew who he was, and he didn’t put on airs or pretend around people. I think that was appreciated by people who can’t always tell if somebody is being straight with them.

When they’re coming on to you with one thing or another, you become a little more guarded. I think that people in famous roles just appreciate it when somebody is coming from a clear straight place, with no bullshit.

John guarded his privacy so much because, as he used to say, “If they know I’m somebody, it changes everything.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Art Thompson is Senior Editor of Guitar Player magazine. He has authored stories with numerous guitar greats including B.B. King, Prince and Scotty Moore and interviewed gear innovators such as Paul Reed Smith, Randall Smith and Gary Kramer. He also wrote the first book on vintage effects pedals, Stompbox. Art's busy performance schedule with three stylistically diverse groups provides ample opportunity to test-drive new guitars, amps and effects, many of which are featured in the pages of GP.

“We’re Liverpool boys, and they say Liverpool is the capital of Ireland.” Paul McCartney explains how the Beatles introduced harmonized guitar leads to rock and roll with one remarkable song

"When they left town, I went to the airport and got to meet Ritchie, and he thanked me for covering for him." Christopher Cross recalls filling in for a sick Ritchie Blackmore on Deep Purple's first-ever show in the U.S.