“Nobody Can Be the Best Guitar Player. There’s No Such Thing”: Mind-Blowing Guitarist Harvey Mandel Riffs With ‘GP’ on His Music, Guitar Technique and a Certain Player by the Name of Eddie Van Halen

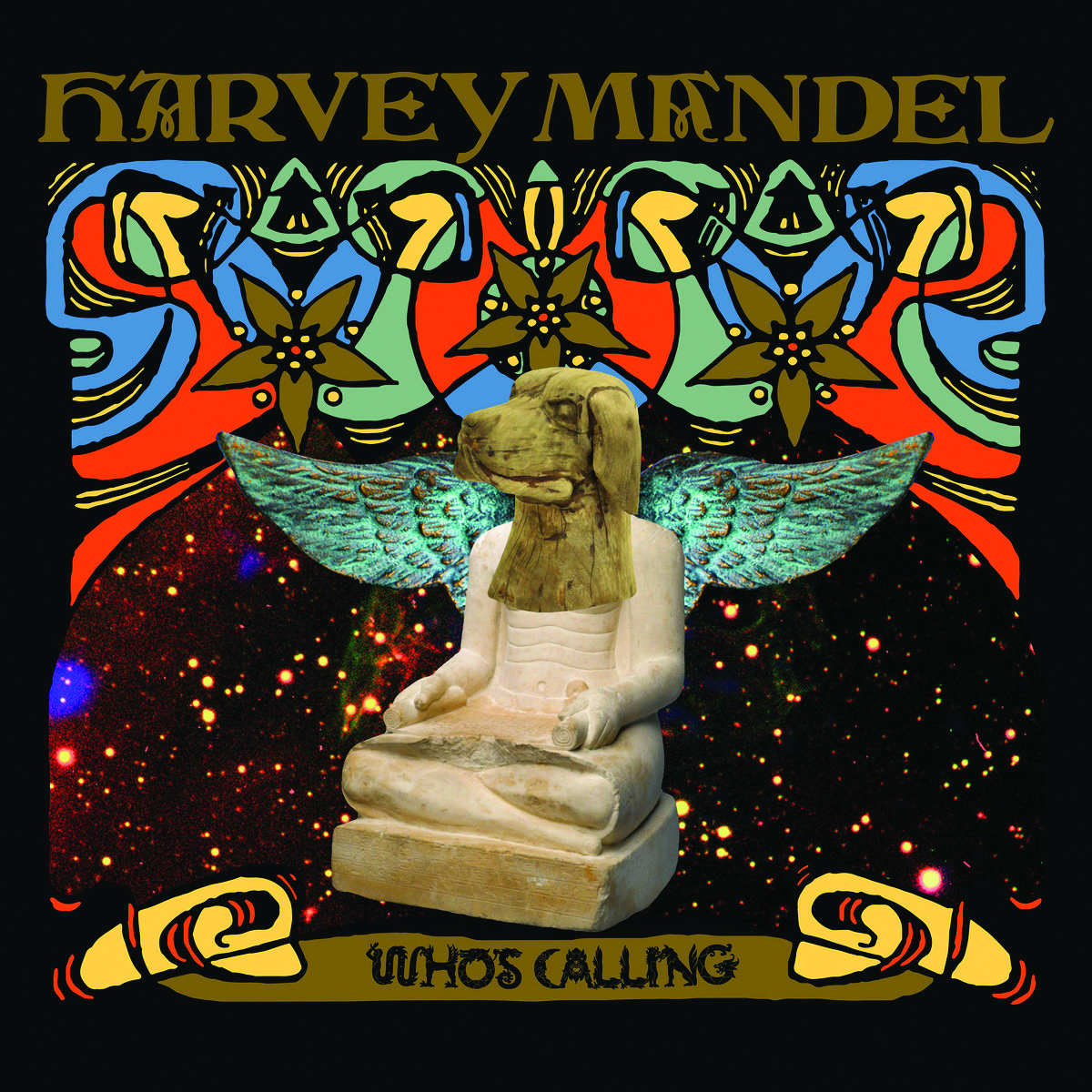

Fifty-five years since his solo bow, “The Sustain King” shows no sign of slowing down on his latest, ‘Who’s Calling’

Two landmark guitar releases, both solo debuts, came along within a few months of each other in 1968 to open my youthful ears and blow my 14-year-old mind. And yet, one so completely overshadowed the other as to render it to relative obscurity. I’m referring to the near-simultaneous releases of Jeff Beck’s Truth, which came out on July 29 of that year, and Harvey Mandel’s Cristo Redentor, issued that November.

Beck, of course, was already famous, having succeeded Eric Clapton in the wildly popular Yardbirds in 1965 and appeared with the band the following year in Michelangelo Antonioni’s film Blow-Up. He also had major-label backing for his solo debut, courtesy of Epic Records. Mandel had already put in his time on Chicago’s active blues scene, making his recording debut in 1966 on Barry Goldberg’s Blowing My Mind and appearing on 1967’s Stand Back! Here Comes Charley Musselwhite’s Southside Band, a seminal recording that, along with the Paul Butterfield Blues Band’s East-West released that same year, bridged the gap between blues and rock and roll.

Harvey’s solo debut on the smaller Dutch-American Philips Records – the same label that had released albums by Edith Piaf, Jacques Brel and the Singing Nun – simply did not have the visibility or promotional muscle to compete against a major-label juggernaut like Epic.

While both albums were life-altering experiences for listeners back then, and they continue to stagger to this day, Mandel’s instrumental solo debut was an overlooked masterpiece. Produced by Abe “Voco” Kesh (née Keshishian), a San Francisco radio DJ and producer who helmed Blue Cheer’s Vincebus Eruptum (which included their hit cover of Eddie Cochran’s “Summertime Blues”), Mandel’s Cristo Redentor was a landmark melding of rock, jazz, blues, country, quasi-classical and soul, with some experimental guitar work thrown in for good measure.

That includes his use of backward guitar effects, a manual tape-flipping process introduced by the Beatles on “I’m Only Sleeping,” from 1966’s Revolver, and perfected by Jimi Hendrix on the title track to 1967’s Are You Experienced. Harvey’s infinite sustain on his Les Paul goldtop – his entire solo on the title track consists of a single note sustained over the percolating groove for an astounding 56 bars – is why he was later dubbed the Sustain King.

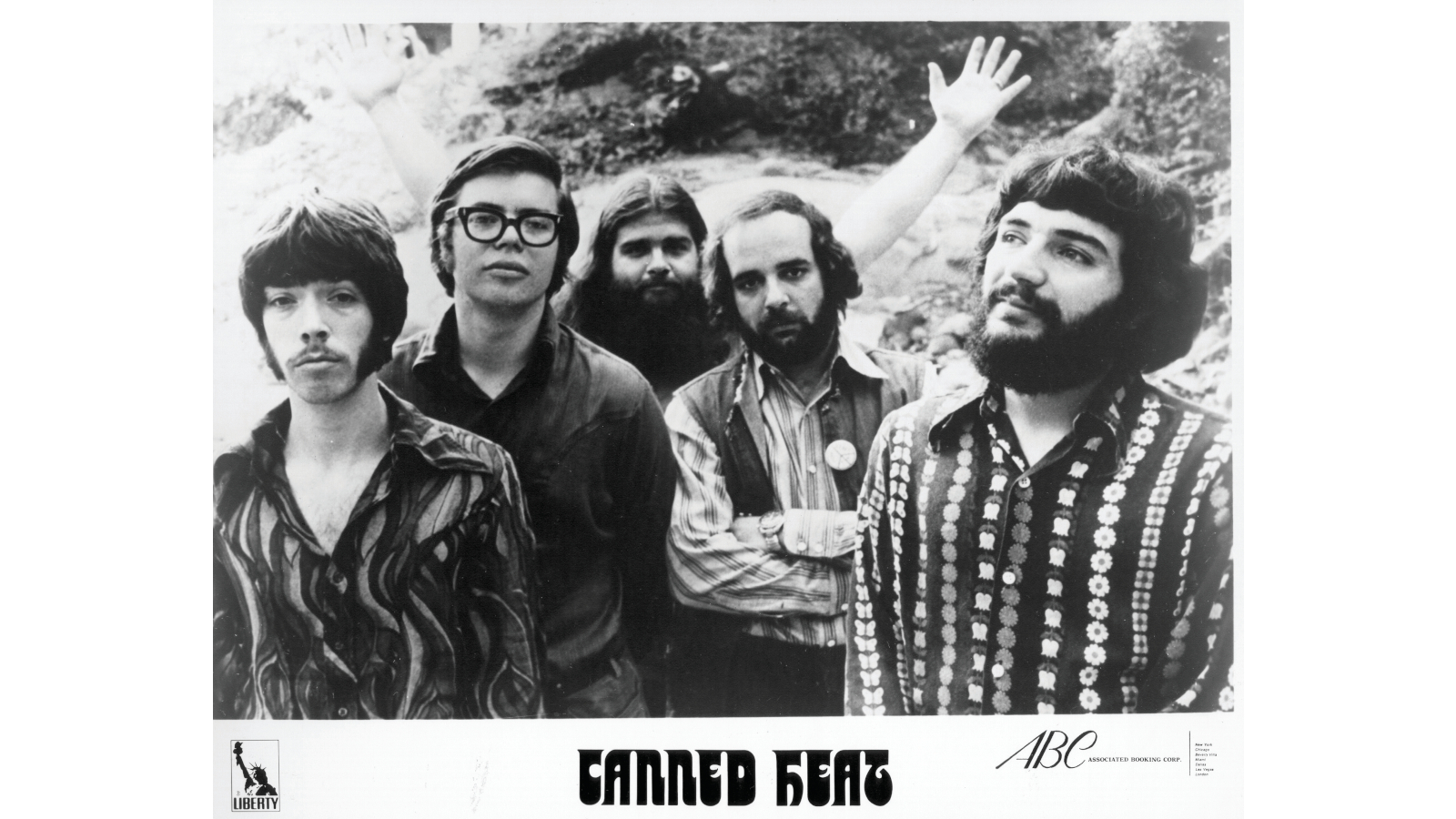

Cristo Redentor was ahead of its time and still sounds fresh and invigorating today. Accurately described in reviews in 1968 as a “gently psychedelic album,” it garnered enough underground attention from guitar aficionados to help launch Mandel’s solo career. He was invited to join Canned Heat in 1969 and appeared with the group at the Woodstock Music and Arts Festival, where his controlled use of feedback near the end of the band’s signature tune, “On the Road Again,” and wicked finger vibrato and string bends on the shuffling “I’m Her Man” were highlights of his performance.

Harvey would subsequently join forces with blues violinist Sugarcane Harris to form the band Pure Food and Drug Act and also play with John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers in 1971. He was later recruited to play on the Rolling Stones’ 1976 album, Black and Blue, unleashing his patented licks on the funky “Hot Stuff” and the ballad “Memory Motel.”

On his own, Mandel quickly followed up the success of Cristo Redentor with 1969’s Righteous, with string and horn arrangements by noted jazz arranger Shorty Rogers, and 1970’s Games Guitars Play, which featured more of his signature sustain tones and backward guitar effects. After parting company with Philips, he released a succession of four albums on the Janus label, including 1972’s The Snake and 1973’s Shangrenade, the latter of which introduced his use of two-handed tapping on the fretboard, a trick that would later be picked up by a young Eddie Van Halen after seeing Harvey performing at the Whisky a Go Go on Sunset Boulevard in West Hollywood.

Following the release of 1974’s Feel the Sound, Mandel would experience a 20-year recording drought before putting out his eighth album as a leader, 1994’s Twist City. He has released 11 albums since then, the most recent being 2022’s Who’s Calling, his second for the Tompkins Square label. Created in the privacy of his home studio, utilizing primarily his ornately painted Parker Fly Mojo with DiMarzio pickups (which he’s dubbed his Snake guitar) directly into Pro Tools, Harvey’s latest has him interacting intuitively with pre-recorded rhythm tracks laid down by bassist Andy Hess and drummer Ryan Jewell, both of whom also recorded live in the studio with Mandel on 2016’s Snake Pit.

Dazzling chops and sustain lines abound on tracks like “Robo Snake,” “Crazy Town” and the title track. And his use of tightly orchestrated overdubbed guitar parts on tunes like “Moon Talk” and the funky “See You Around” give the effect of Harvey playing through a harmonizer.

Though plagued since 2011 by health issues – he’s mounted a GoFundMe page to help defray the cost of multiple cancer surgeries – the Sustain King is still wailing with abandon at the age of 77, as Who’s Calling so readily reveals.

It was a great treat for me to interview Harvey Mandel, who I first saw play at Humpin’ Hannah’s in Milwaukee, circa 1972. He was calling from his home in San Francisco.

This new album was done very differently than your previous ones.

Yes, Who’s Calling was completely different than Snake Pit. We did that all live at Fantasy Studios. In fact, we were one of the last to go in there and actually record live before they permanently closed the place. So the new record was an idea of Josh Rosenthal from Tompkins Square Records, who also did the Snake Pit album. He put the two guys, bass player and drummer, in a studio and just had them lay a few different grooves down. Then they gave it to me, and everything else you’re hearing is me in Pro Tools with my guitar and a few toys.

The entire thing was done with no amplifier. I would put the guitar through a few pedals and then into Pro Tools

Harvey Mandel

I was actually able to take chunks of their stuff and, through musical trickery, through knowing how to work Pro Tools so well, I was able to come up with every one of those songs that sound really original. They were all built off of these simple little beats and drum things. And the entire thing was done with no amplifier. I would put the guitar through a few pedals and then into Pro Tools.

And I don’t like to brag, but technically, playing-wise, this is definitely some of the best that I’ve ever done. If you heard the rhythm tracks just by themselves, it would be hard for you to imagine how I ever came up with what I did on these songs. But I just heard it my mind and knew what I could do.

I’d go into my little studio with the Pro Tools setup and do a hundred takes if I felt like it, just experimenting with different ways to play over those rhythms. I always try to come up with some magic for each song. I’m not a music guy, where I can sit and read notes or transcribe a solo and all that. I just never got into that. But God gave me a good ear.

It sounds like you’re a very intuitive cat.

I can hear what’s good for songs, especially in the studio by myself. If you go in with a band, the bass player knows his part, the drummer knows his part, it’s live in the studio and you can only take it so far. But when in my home studio, I can experiment and come up with all kinds of weird shit that I would never be able to do in a regular studio situation without spending hundreds of thousands of dollars in studio time. But I could sit here in my own studio for four or five hours and come up with total magic.

To me, that’s the best way. I hear a song, the track is all worked up, it’s all EQ’d, it’s all ready to go, and I can lay the magic right in there where I want it.

What guitars are you currently playing?

I have eight or nine guitars that are my special ones that I use on everything. If I want to get a Strat sound, I have a John Petrucci Music Man guitar. And then I’ve got three custom Ken Parker guitars that I got way back when they first came out. These are the original ones, the best of Parker back then, because that’s when Ken was doing all the work himself.

I remember Pat Martino played a Parker Fly for a while.

Yeah. That’s how I got into the Parker thing. I was at the NAMM show and I had just gone over to see Pat Martino, who I was friends with. He was there with the Parker representative, and he said to the guy, “You should get Harvey Mandel on Parker.” The next thing you know, a few days later, I got a brand-new first Parker guitar in the mail. And after that, I ended up with another two or three of them.

The one custom job they made for me, I call it my Snake Guitar. It’s got all that beautiful artwork and stuff. That’s probably the main one that I use now. I played it quite a bit on Who’s Talking. And for special things I have all these other guitars. But my main all-round guitar is the Snake Guitar. I can play all the blues and can do all the bending; I can do all the creative shit. And the neck is not so big that I can’t chord it properly. That’s still my best all-round guitar.

Truth is, there’s so many good guitars today it’s hard to pick one from another

Harvey Mandel

Does your Snake Guitar have a whammy bar on it?

Yes, but not a real dive-bomb whammy, like the Ibanez JEM 7, the Steve Vai guitar that I got. You can grab the whammy bar on that thing and swing it around without breaking the guitar. It’s a whole different system. The Parker whammy is a different system than a Floyd Rose, who really got it all together with the whammy. I would like to get a setup like that on the Snake Guitar. But I don’t do a lot of crazy whammy stuff on that guitar. I have other guitars so I can do all the crazy stuff. Whatever is called for, I have the guitar that’ll take care of business.

If you go back to Cristo Redentor and Righteous, your tone is so warm and creamy. I’m guessing it’s a Les Paul.

Not totally. I had some other Gibson axes on that album too, maybe an ES-355 for some things. I go through periods. I had a Gibson period; I had a Strat period. I like the Ibanez. Truth is, there’s so many good guitars today it’s hard to pick one from another. But I’m really happy I got the Parker guitars. They’re so light. They’re good for my little body. I have small hands, so it’s easier for me to control that one. It’s much harder for me to play, like, a full-sized Strat or other guitars like that, because my hand isn’t as big. If you look at Steve Vai’s fingers, the guy’s got, like, giant long fingers. I’m just the opposite. I got small hands.

Do you still have that Les Paul from Cristo Redentor in your arsenal?

No, that’s a sad story. I had this guitar tech guy in Chicago who was doing a lot of stuff for me – it wasn’t long after I did Baby Batter [1971] – and he tried to put a Floyd Rose on that guitar. But to do it, he had to scoop out a hunk of wood in the back to put the springs in. As soon as he did that and we put the guitar back together, it was ruined. The sustain was gone and we could never get that guitar to sound right again. I ended up giving it away. It was one of the best guitars I ever had. The tone was astronomical. I could get another Les Paul, but it wouldn’t be the same.

Cristo Redentor was an amazing landmark. When it first came out, and even now, it sounds like a revelation. The stuff that you’re innovating on that record is unbelievable. You open with this Duke Pearson tune with strings, and you injected backward guitar throughout that record. Where were you coming from with all that?

That had to do with my producer, Abe Kesh. With my crazy stuff and his crazy ideas and all the stuff we put together, we came up with a lot of original sounds.

How did you pull off the backward guitar on Cristo Redentor and Games Guitars Play?

Back then, I had to do it the hard way. We had to get the two-inch reel, turn it around on the machine and play over a certain section. So all I could do is determine the beat to make sure that I was locked in and in the right spot. And just through experience and experimentation, I was able to play licks that worked. So when they put the tape back on proper and you’re listening to it going in the right direction, it sounded perfect the way I did it. I didn’t plan it out, but I had the ability to hear the tape backwards.

And it was a miracle, because I was flying by the seat of my pants. It was the first time I was ever doing any of that stuff in the studio, but it all worked out great. I’d know where the beat was, and I was able to set up the section with the ingenuity of, “This is where I was going to be utilizing that effect.” And I could start a little early, go a little late, and we just edited that out. No problem.

Nowadays, I can get a lot of that sound just from pedals. I don’t have to worry about syncing up a backward part by turning the tape over and recording. With Pro Tools, you can turn shit around. You can do anything. Anything you can do with the tape machine, you can do with Pro Tools, if you know what you’re doing.

Anything you can do with the tape machine, you can do with Pro Tools, if you know what you’re doing

Harvey Mandel

One of the things that really jumped out at me when I heard Baby Batter for the first time, and when I listen to it now, is the very aggressive finger vibrato that you got going on that album. It’s like B.B. King on steroids.

Yeah, there’s no whammy bar in there. That was just pure Les Paul and my fingers. That’s one of the things I’m good at. I’m good at getting the sustain. I can imitate all the different vibratos – a B.B. King vibrato, an Albert King vibrato. Sometimes I pull the string down, sometimes I push it up. Sometimes I shake the entire neck up and down. Other times I shake just the wrist. B.B. King’s a wrist guy.

So when I was learning, I tried to learn all the different ways you could do it, and my own style came out of that. So now when I’m playing, I’m not even thinking about it. When I hit a certain note and it needs a vibrato, one will automatically be put on there without even having to think about it. If it’s in my mind, it’s already there in my fingers.

You must have gained some of that knowledge from seeing all the real-deal blues cats coming up in Chicago.

Definitely. I used to play down at Twist City all the time. All the good guys were down there, so I was lucky. I got to see everybody. I jammed with Buddy Guy so many times. When you watch Buddy Guy, even though he’s a wild man… he’s not technically real perfect, you know, because he gets a lot of weird sounds on the instrument. But he can play his ass off. Unbelievable bending and shaking and vibrato. And I was able to see that every night in person. It soaked into my brain, and it wasn’t long before I could imitate and do that same stuff.

So you got these things ingrained in you, but you also put a really unique spin on it – your own vocabulary, so to speak.

I try to. Nobody can be the best guitar player. There’s no such thing as the best. I can name the top 10 guys, and each one of them is total magic within themselves. And I’m just trying to be one of those. I have a certain style. I can play certain licks and stuff that nobody else would do exactly that same way.

You’ve been a complete original your entire career. And yet you never broke through to that level of visibility that some guitarists have attained.

It’s unfortunate that I didn’t ever get with a band like a Van Halen, where I had, like, a pop band to get hits, because that’s how those guys all got known. I didn’t get well known because, by the time it might’ve happened, Canned Heat had petered out and I was off on my own. And not being a lead singer was a handicap, of course. I was never able to record any good pop songs, so I ended up being an instrumentalist.

Unless you’re like a Jeff Beck or a Pat Martino, it’s very hard to have a career just doing instrumentals. But I’ve done it on my own level.

You mentioned Van Halen. And, of course, a lot of people have noted that you were doing two-handed tapping long before Eddie Van Halen ever did.

He actually came to the Whisky a Go Go when I was playing there one night in L.A. and saw me do the finger-tapping thing. And, of course, he took off with it – went his own way and did it great. But he totally got the idea from me. He totally took my thing and went nuts with it and did his thing. And now, for the past 40 years, the whole world has been doing finger tapping.

I haven’t played with a pick now in over 10 years

Harvey Mandel

You initiated that technique on your 1973 album, Shangrenade.

Yeah, every song, every note of guitar you’re hearing on that record, except for the rhythm playing, I’m doing finger tapping. All those melodies, everything I did is total finger-tap style. And everything wasn’t about doing the real fast thing like Eddie Van Halen did. It’s more slow melodies, some soloing, but still going back and forth from one hand to the other, totally tapping. It’s all fingertips.

Are you still tapping on your records?

Just a very little bit here and there. Of course, we’re hearing some similarities on occasion, but every one of my records is different. Different style, sound, guitar, toys, studio and vibe.

On some of the songs from Who’s Calling, it sounds like you’re doing fingerstyle comping, like on “Crazy Town.”

I’m playing with fingers on every song. I don’t play with the pick. I haven’t played with a pick now in over 10 years. Everything you’re hearing is my thumb and my three fingers on the right hand – mostly the thumb and middle finger. I call it hybrid picking, but there’s no pick – it’s all fingers. I can get that fatter, fleshier tone using my fingers. I could do the same lick with a pick and it won’t sound the same; it’s always a little thinner, a little tinnier.

The fingers give a magic sound. And I just happened to do it one day on the gig, and I thought, Let me try to play all of the songs without using the pick. So I did it all night, and it was the best I’ve played in years. After that I said, “That’s it. I’m done with the pick.” And now it’s just natural for me to work that way.

And it doesn’t effect your speed on your solos?

No. The only thing a pick can do that I can’t do is, like, shred metal guitar. That’s not my bag anyway.

But look at jazz players like Joe Pass, who can play incredible runs at fast speeds. And he used to play with his fingers. It depends on the person. If it’s in your mind, if you can hear it, if you can see it and you’re good enough, you can get away with it.

Wes Montgomery played lines that were so unbelievably fluid, all without a pick.

Yes. He could take his thumb and make it work like a pick. I can’t quite do it all with the thumb, so I use thumb and middle finger, which is different than everyone else. I’ll use my thumb and my other fingers for chording, claw style.

Other times I’m just using my thumb and middle finger for playing single-note lines and I’ll have all the speed I need. And using fingers, it all comes out sounding perfect. Playing with a pick can be great in the hands of the right person. I’m not that person. I’m not as good with the pick as I am with my fingers.

Once I make a record, I’ve already heard it 100 times. After that, I’m done with it

Harvey Mandel

On some of the tracks on Who’s Calling, like “Robo Snake,” “Moon Talk” and “Last Walk,” it sounds like you’re playing through a harmonizer.

Not a harmonizer on the guitar as far as an effect, but rather harmonizing with real guitars doing it. All the parts you hear are me playing them. There is no harmonizer on any of this record.

You did that on past recordings as well, like on Games Guitars Play, where you had a multiple harmony guitars thing, sort of like the Allman Brothers.

Yeah, on all my records, if you’re hearing harmonies, you’re hearing the real guitars doing parts. I can’t even think of anything that I’ve done where I used a harmonizer. And I have those tools. I have the Eventide H9 Harmonizer, which I can get just about any guitar sound on planet earth with. The equipment I have now is good because I surely can get all the different sounds that I want. I can imitate or innovate.

Do you listen back to your old records?

No. Once I make a record, I’ve already heard it 100 times. After that, I’m done with it. Once in a while I’ll go back for the fun of it and listen to Baby Batter and go, “Damn! I actually could play good!” And that was, like, 50 years ago. Of course, everyone does all that stuff now, but back then very few people played like that.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Bill Milkowski's first piece for Guitar Player was a profile on fellow Milwaukee native Daryl Stuermer, which appeared in the September 1976 issue. Over the decades he contributed numerous pieces to GP while also freelancing for various other music magazines. Bill is the author of biographies on Jaco Pastorius, Pat Martino, Keith Richards and Michael Brecker. He received the Jazz Journalist Association's Lifetime Achievement Award in 2011 and was a 2015 recipient of the Montreal Jazz Festival's Bruce Lundvall Award presented to a non-musician who has made an impact on the world of jazz or contributed to its development through their work in the performing arts, the recording industry or the media.

"Why can't we have more Django Reinhardts going, 'F*** everybody. I'll turn up when I feel like turning up'?" Happy birthday to Ritchie Blackmore. The guitar legend looks back on his career in an interview from our December 1996 issue

"Get off the stage!" The time Carlos Santana picked a fight with Kiss bassist Gene Simmons and caused one of the guitar world's strangest feuds