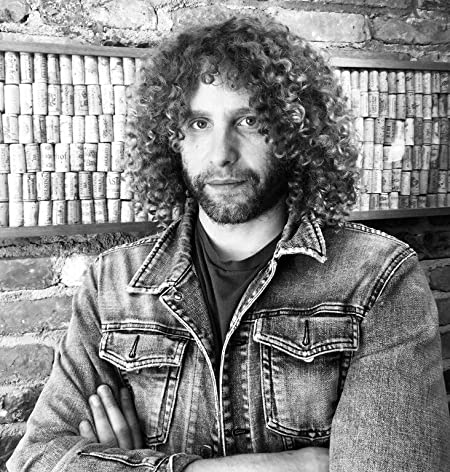

Jake Kiszka Discusses Rock’s Unstoppable Evolution and Balancing Beauty and Savagery in Greta Van Fleet’s Sound

'The Battle at Garden’s Gate' sees the Michigan rockers take their songwriting into uncharted territory.

When Greta Van Fleet first exploded onto the scene a few years back, the band was lauded as much for their riff-centric, groove-heavy approach to rock and roll – something of a rarity in this day and age – as they were scrutinized for their stylistic adherence to rock icons like Led Zeppelin.

Early hits like “Highway Tune” and “Safari Song” certainly traded on blues-drenched boogie riffage, crashing rhythms, and gloriously histrionic vocals.

But on releases like the 2017 EPs Black Smoke Rising and From the Fires, as well as their 2018 debut full-length, Anthem of the Peaceful Army, the young quartet from Frankenmuth, Michigan demonstrated that they were more than a mere arena-rock retread, stretching out into pastoral, folky meanderings, proggy epics, country-tinged jams, and dark-hued, metal-adjacent workouts, among numerous other styles.

Even so, nothing in Greta Van Fleet’s short past could prepare listeners for The Battle at Garden’s Gate (Republic). It’s a sprawling and challenging collection of tunes that for the most part leaves behind the upbeat, uptempo hard rock of previous releases in favor of a darker, denser, and overall deeper experience.

“There’s a lot of beauty in the album, and there’s a lot of savagery in there, too,” says guitarist Jake Kiszka, who plays in the group with his brothers Josh (vocals) and Sam (bass), and drummer Danny Wagner.

Beauty and savagery do abound, from the slow-burning opener, “Heat Above,” which unfurls in a swirl of acoustic and electric guitars, keyboards, and strings (the band have called it “a dream in the clouds”) to the doomy and turbulent first single, “Age of Machine.” Then there’s the massive, almost nine-minute closer, “The Weight of Dreams,” which climaxes with a breathtaking extended lead guitar freak-out.

Throughout its dozen songs, The Battle at Garden’s Gate shows Greta Van Fleet swinging for the sonic fences at every turn, and in the process hitting more than a few out of the park.

According to Kiszka, that musical ambition is baked into the Greta Van Fleet mindset. “The rules are just a framework,” he says about adhering to rock-and-roll traditions. “You have to break them in order to create what doesn’t already exist.”

Kiszka recently sat down with Guitar Player to discuss Greta Van Fleet’s rule-breaking new album, as well as the future of rock and roll in general and, more specifically, the guitar as a means of expression within the genre.

“I think what’s going on now is there’s a lot of invention and experimentation,” he says. “And that’s really important to the new form of rock and roll and its evolution and survival for our generation and the next generation.”

As for the guitar? “People are still so fascinated by it,” he continues. “I know I certainly am.”

In terms of songwriting and sound, The Battle at Garden’s Gate is very different from the group’s debut album and its two earlier EPs. I’d imagine this is due at least in part to the fact that the new songs were conceived largely on the road, during your last few years touring the world. Whereas earlier songs like, say, “Highway Tune,” were written in your parents’ garage. Suffice to say, your day-to-day experiences must have changed greatly.

Oh, yeah. I suppose it’s a reflection of a lot of the experiential aspects of what goes down on the road – the different places, people, and cultures we’ve seen in and around the world on tour.

Because you’re right, I think we were a garage rock and roll band to a certain degree at the beginning, whereas The Battle at Garden’s Gate is a different way of making music in the capacity that we do as a band, together. It’s definitely approaching songwriting from a different angle, and there are a lot of experiences that informed the music.

Can you point to anything in particular that was exceptionally eye opening?

Maybe some of the things we saw in South America, where we’d get offstage and grab something to eat after the show. People would be cleaning up the venue, and there would be beer cups and leftover food on the ground, and somebody sweeping the floor would pick up a piece of food and put it in their pocket. You see that and it saddens you.

Some of those elements come through on the album. But when you’re listening to the album as a whole and you admire it as a full body of work, I think what’s being represented is that there is still a lot of hope in the world. We’ve seen so much great positivity and peace.

But then, on the other hand, there’s also a lot of poverty, a lot of starvation, and a lot of things that I think society needs to have a sense of reformation about. And if you consider that an artist has a role of holding up a mirror to society, then it was important to us to speak about some of these experiences.

Looking at the record from a musical perspective, the sound is very hard-hitting, but it’s not as much of an immediate listen as some of your past work. It’s not just big riffs, big choruses, and big solos; you have to be drawn in over repeated listens. Did that shift in temperament require you to alter your guitar approach? It seems as if you’re using your instrument more to color the songs as opposed to always being the primary driver.

I did want to approach the guitar on this album in a certain way, and I think you’re right: It is almost like painting with colors. I wanted a bit more intricacy, a bit more depth, and a bit more nuance.

Some of the tracks are riff-driven and hard-hitting and are contextually very much that type of song. But then on some of the other songs – like “The Barbarians” or “The Weight of Dreams” or “Trip the Light Fantastic” – there’s a bit more intimacy, I suppose, and they’re characterized by a particular technicality in the approach.

Sometimes my objective there was intentional, and sometimes the song really just called for it. “Broken Bells” is another good example, or “Tears of Rain.” These were songs that were about capturing a type of intimacy that required a different approach to songwriting.

One track that harks back to the more driving, riff-centric approach that we think of as the traditional Greta Van Fleet sound is the first single, “My Way, Soon.” I love the guitar tone on that one. It’s dirty and aggressive, but it also has a lot of definition and almost a “twanginess” to it.

On this record, I really focused on the nuances in my playing, and I think “My Way, Soon” is a good example of that. It’s a sort of highly detailed approach, in which you take something simple and add a more complex layer to it. As for the “twanginess” that you mention – I think it’s interesting you say that, because it probably has more to do with the technique than the tone.

Something similar would be “Highway Tune,” which has a twangy type of riff as well – the hammer-ons and pull-offs and the articulation of the playing. But, in general, we were doing a lot of different things sonically this time. We had basically a month, month and a half in L.A. in the summer of 2019 to really craft this record and to be particular about tonality and about what equipment we were using. We had time to work it out.

What was your main gear setup this time around?

We had so much stuff flying around when we made this album. As far as amps go, I always have a Marshall Astoria and a Bletchley with me. Bletchley is a boutique amp company out of Detroit.

When we were recording there early on and kind of getting our legs under us, the owner, Daniel [Russell], gave me an amp, and I’ve used it ever since. So I always have those two amps when I’m in the studio. I also had a ’60s Fender Champ, and Greg Kurstin, our producer, brought his Fender Champ into the studio as well, and we were using those in stereo a lot.

We’d put them on opposite sides of the room and mic them, and we’d get some really interesting, really wide sounds. And there was also a Gibson Falcon, and a Vox AC30, which I always have in the studio because it comes in handy for cleaner tones.

Also, a lot of the solos went through either a tweed Fender Deluxe or a ’65 Fender Deluxe Reverb that belonged to our engineer. And we used a [Roland] Space Echo on some of the solos, like on “Built by Nations” and “Broken Bells,” and then panned it manually, so you hear it flying all around. There was a lot of experimentation.

How about guitars?

The main guitar, the workhorse, I suppose, was my ’61 Les Paul. I also used a blond ’62 Fender Telecaster, and I don’t think I’ve ever used a Tele on previous recordings. But I used it a lot for overdubs this time. And then I had a ’60s sunburst Stratocaster, which was interesting, because I was looking for a guitar with a whammy bar that we could pan in stereo, and Greg Kurstin said, “Well, I had this Stratocaster, but I gave it to my friend’s son.”

So the kid came in and brought the guitar with him, and we let him sit there while we recorded with it. We put it on the song “The Barbarians.” You can hear it in the middle solo section. Then I remember there was an Epiphone Casino, which is on the “Built By Nations” solo. I like the Casino because the neck is really thin, which is very much like that ‘61 Gibson that I like.

People say that rock and roll is a minority, and I’m sure it is. But it can cut through concrete when it needs to

There’s a certain amount of rock traditionalism in Greta Van Fleet’s approach. At the same time, as we’ve been discussing, you really push the boundaries of your creativity on The Battle at Garden’s Gate. Looking at rock and roll in 2021, how do you strike that balance where you’re retaining a connection to earlier sounds but also staying modern and forward-thinking?

I think this is a really interesting thing to consider. What is the newest forum of contemporary rock and roll? Where does it stand as a genre and how is it affected by the musicians involved? People say that rock and roll is a minority, and I’m sure it is. But it can cut through concrete when it needs to, especially because it is such a minority.

And there are so many great contemporary rock and roll bands. You have the White Stripes, who were path pavers, and then everything that came after them, like Gary Clark, Jr., the Black Keys, Cage the Elephant, Alt-J, and Aaron Lee Tasjan, and then Ida Mae, Goodbye June, the Struts, Dirty Honey, us in a sense.

We’re all kind of in this orb of rock creation and evolution to a certain degree. All you can do is take the traditional aspects of songwriting and the instrument in your hands – and in this case, we’re talking about the guitar – and learn the rules and then break them and restructure them.

How would you extend that idea to your approach on the guitar?

What’s interesting about the guitar is that it represents practically the entire genre of rock and roll. Which is fascinating. But at heart it’s a tool for creating. And it’s a tactile thing that involves your fingers, but also your heart and mind. As far as moving forward with it, one thing that inspires me is technology.

There’s so much new technology being incorporated into guitar playing. Take a song on the new album like “Trip the Light Fantastic,” where there’s a Mellotron pedal, a [Electro-Harmonix] MEL9, that is incorporated into the guitar’s tonality.

It’s quite a unique sound and something that I’ve never heard before. So part of it is about guitar players stretching the realm of capability and looking at what’s possible with new technology or new guitars or new concepts, and just thinking outside the box of traditional thought.

In addition to artists working within rock and roll and other styles, there are so many great guitarists that live in the digital world – i.e., YouTube, Instagram, and other social-media platforms. How do you view all the different ways the guitar is utilized today?

I think there’s a place for all of that in the world. And it’s sort of a reaffirmation that the guitar is still such a classic and important staple of modern society. By extension, you could say that guitar’s survival is more proof that rock and roll isn’t dead.

Even with these guitar players on Instagram, YouTube and TikTok who may just do a very specific thing – the people watching them are going to go back and look at the guitar players that predated them, and that will influence many guitarists of our generation and the next, who will start writing their own songs on guitar.

For that matter, you have groups like the Foo Fighters and Arctic Monkeys, and even the classic rockers like the Who and the Rolling Stones, who will still go out and play three-hour concerts that showcase the guitar. It just shows that the guitar has survived in such an interesting way.

What advice you would give to a young guitarist starting out in rock and roll?

I think that persistence and dedication and timing will get you anywhere. If I could say something to my younger self when I was first playing guitar, I would say that. And I would add that you should just continue with your craft, because, as I’ve gotten older and have become a more proficient player, I’ve realized that I’ve become able to speak through the instrument better.

And it has become an outlet that has guided me, not even just musically or instrumentally but also in my personal life. It’s always been an outlet, whether I’m ever down or up. As a form of expression, the guitar is mind, body, and spirit. So whatever you’re doing with it, just keep going.

- The Battle at Garden’s Gate is out now via Lava Music.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Rich is the co-author of the best-selling Nöthin' But a Good Time: The Uncensored History of the '80s Hard Rock Explosion. He is also a recording and performing musician, and a former editor of Guitar World magazine and executive editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine. He has authored several additional books, among them Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, the companion to the documentary of the same name.

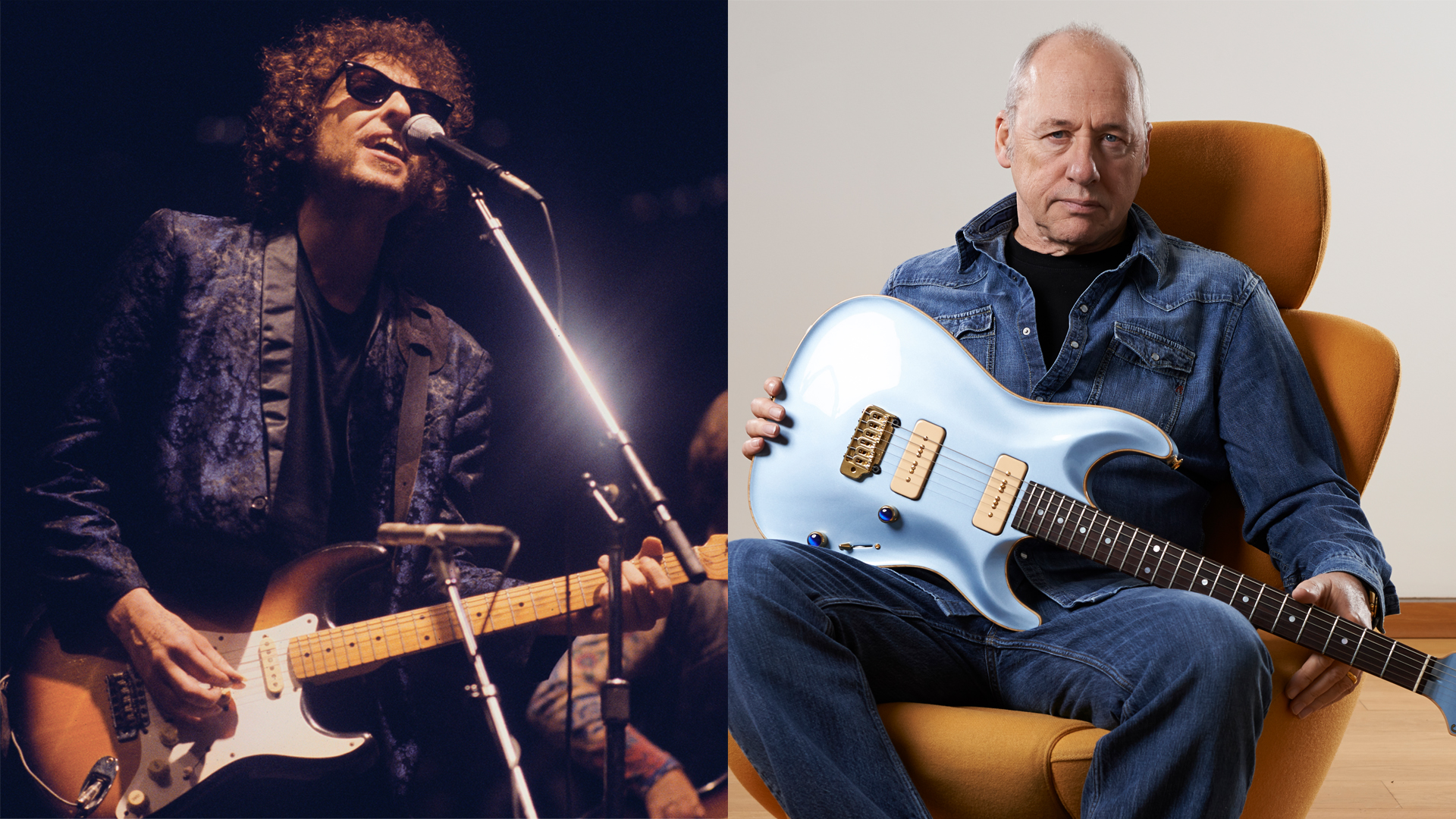

“I knew he was going to be somebody then. He had that star quality”: Ritchie Blackmore on his first meeting with Jimmy Page and early recording sessions with Jeff Beck

“He used to send me to my room to practice my vibrato.” His father is the late Irish blues guitar great Gary Moore. But Jack Moore is cutting his own path with a Les Paul in his hands