Usually, if a band requires that a wall of security guards be stationed shoulder-to-shoulder in front of the stage before they start playing, the implication is that things are about to get rowdy—maybe even a little violent. But while there was a squad of security hulks at Green Day’s recent concert at the Palladium in Hollywood, those 16 dudes didn’t seem to have policing the crowd as their primary purpose. If anything, the behemoths were provided, with love, by the band to act as a human safety net—a 32-arm insurance policy guaranteeing that no crowd surfer broke his or her face after tumbling over the barricade.

Yes, the Palladium fans were rowdy, rabid, and raucous (but not violent), and even though the set was 135 minutes long, the moshing and crowd surfing never ceased. That’s because even in 2017—after multiple Grammy wins, induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and sales of more than 75 million records— Green Day still makes huge venues feel like the small, anything-goes pressure-cooker punk dens in which they got their start in the Bay Area back in the ’90s.

“The way to keep an arena show feeling intimate is to somehow break down the barrier between you and the audience,” says Green Day’s Billie Joe Armstrong. “One way we do that is to bring people up on stage with us. When I was 12, I saw Van Halen, and as I watched Eddie play a big guitar solo, I was thinking, ‘Oh my god, what would it be like to be up there on that stage? That is just insane.’ But in the back of my mind I was like, ‘That will never happen. That would be like catching a foul ball while watching a baseball game from the top deck of the Oakland Coliseum.’ But there’s something genuine that happens when we bring someone up to sing or play guitar—something that causes the crowd to get so into it that everybody kind of becomes one. It’s the ultimate form of unity.”

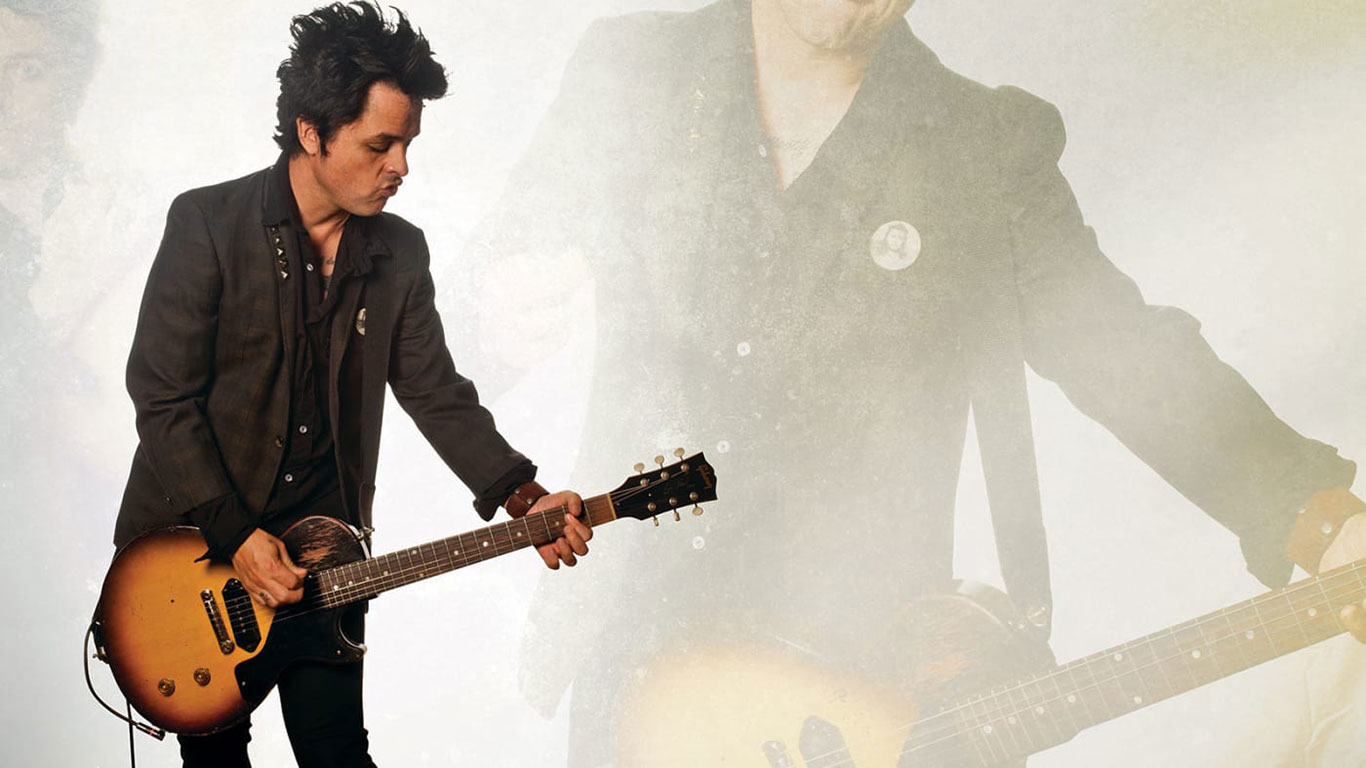

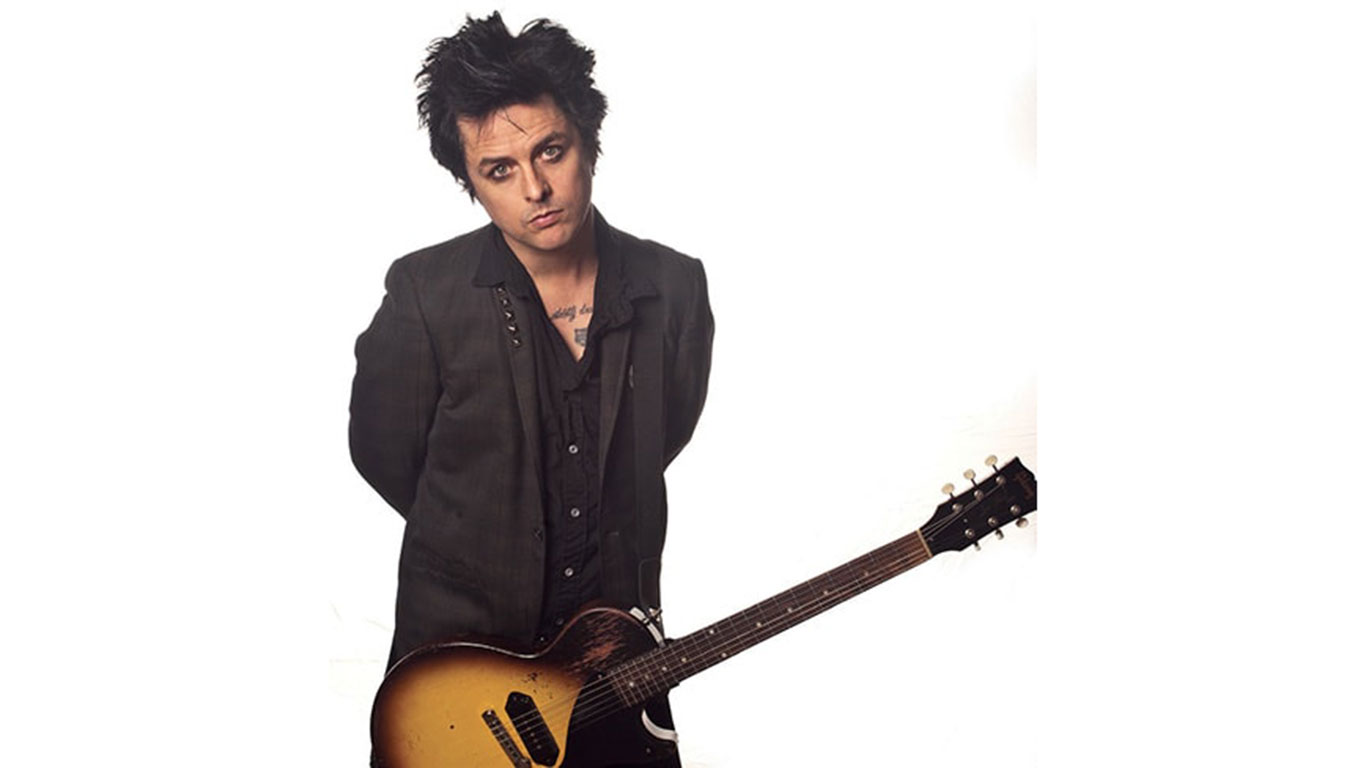

Green Day is 30 years old now, but the band doesn’t seem to have lost any of its appeal. The original core trio—Armstrong, bassist Mike Dirnt, and drummer Tré Cool— is still intact, and their allure is as strong as ever. That allure lies in the group’s anthemic, super-singable choruses; thunderous, mosh-worthy riffs; inclusive, peace-punk ethos; and fearless lyrical stances on everything from mass shooters and homophobia to police protests and the chaotic climate of American politics. And Green Day’s popular magnetism is still working commercially, as well—the band’s new album, Revolution Radio [Reprise], landed at #1 worldwide the first week of its release.

For guitar players, though, Green Day’s appeal starts with Armstrong’s delicious command of the almighty eighth-note. Unless you were born without a single rock and roll bone in your body, you’d be hard-pressed not to find several Green Day riffs you’d have fun playing through a pair of blazing Marshalls.

Armstrong’s energized eighth-notes are part of a musical lineage that traces back through the Ramones and the Beatles, all the way to the guy who took eighth-note-driven boogie-woogie piano parts and applied them to an electric guitar—the great Chuck Berry (who turned 90 years old at press time and announced a new album). That’s why it’s only fitting that on Revolution Radio, Armstrong pays homage to “Johnny B. Goode”—the Chuck Berry classic that helped launch the rock-guitar revolution— in his new song, “Forever Now.”

“I never learned to read or write so well,” sings Armstrong, “but I can play the guitar until it hurts like hell.”

The first time I saw Green Day was in 1993. You were playing a free lunchtime concert in Berkeley for about 300 people, and I was amazed to see that probably 297 of them were singing every song lyric-for-lyric. I knew instantly you guys were going to be huge. Then, your first major label album, Dookie, came out and it sold ten million copies. Do you ever miss the days before worldwide fame?

Sometimes. The thing I miss about those days is just hanging out with people in different towns and sleeping on people’s couches. Those were the most intimate years we ever had. The tour for our first indie album on Lookout Records in 1990, 39/Smooth, was when I met [my wife] Adrienne, and also when I met Jason White [Green Day’s touring guitarist]. So I have these long-lasting relationships that date back to when I was 18 years old.

I do a bit of teaching at Musicians Institute, and I can’t believe how many young, dedicated guitarists come in and want to play and sing Green Day. How do you feel when you walk in a room and see some 19-year-old who doesn’t even know you’re there playing “Basket Case,” or one of your other songs?

It’s the ultimate form of flattery. In fact, sometimes it goes beyond flattery, because it’s one thing to sit at home in your bedroom and learn how to play a band’s songs, but I run into a lot of people who say, “The first song my friends and I learned together was ‘Basket Case,’ and now we have a band and write our own songs and have records out.” Hearing that is an amazing feeling. You can’t trade that in.

What I do on guitar is not always easy, but it is always simple, and I think that simplicity has encouraged a lot of young people to play. Back when I was a kid, the big rock bands—the dinosaurs, if you will—were doing things that made you feel like, “Wow, that’s impossible.” But I think when people see Green Day and the way I play, they see it as something that is possible.

Who were some of the guys you dug in your early years?

Angus and Malcolm Young are pretty high up there, because one of the first records I ever bought was AC/DC’s For Those About to Rock. Next on the list would probably be the first Def Leppard records. High ’N’ Dry has some of the best guitar tones I’ve ever heard in my life. They’re so underrated. I know some people think the ultimate rock-guitar sound might be AC/DC, but that Def Leppard stuff is fantastic. They’re great guitar riffs. That was the stuff I cut my teeth on.

Some people might be surprised to hear that Def Leppard is such a big influence. You’re bordering on glam rock there.

I started really getting into playing guitar when I was eight, and when you grow up in a super small town where the only thing you can get is MTV—and there’s hardly any rock radio—that’s what you end up playing. I really dug Ratt’s Out of the Cellar, too. I thought that was good. I also liked Mötley Crüe. Mick Mars is a great guitar player. As for punk, well, I got into punk when most people get into punk—when I was 14 or 15. But there was a life before that for me.

What is the most inspiring guitar performance you’ve ever witnessed?

There have been a few, but one that comes to mind is when I saw the Church play at the Fillmore in San Francisco. It was like a guitar army, the way those two guys [Peter Koppes and Marty Willson-Piper] played off of each other. It just filled that room. That was the first time I realized that alternative-style guitar playing could be unbelievably amazing, too. If you’re wondering what I’m talking about, check out some songs by the Church—like “Reptile” and “Under the Milky Way.”

You’ve had the same guitar tech for years, Hans Buscher. What would you say Hans’ biggest challenge is at a Green Day show?

I think it’s just to make sure that my tone is still good, that everything is working well, and that my guitar sounds just like it does on the records—which is important to me. My setup is pretty straightforward, though it sounds more simple than it actually looks. I have a couple of different Marshalls that I play through, and I have three basic sounds—a clean tone, a medium-level overdrive, and then the big stuff. Hans is also responsible for switching all my tones during the songs—like giving me a big volume boost during solos, calling in a delay in one or two places during the set, and getting this one nasty sound I use during the intro to “American Idiot.”

What was your go-to guitar and amp recipe for the overdriven sounds on Revolution Radio?

It was a combination of different things. For starters, I often had my ’56 Les Paul Junior plugged into an old Park head that has been totally rebuilt. Another underlying thing on a lot of parts is a Rickenbacker 360—like the ones Peter Case and Peter Buck use—through a Divided By 13 head. Those guitars are so punchy. I was going for something that was in between Paul Weller, Steve Jones, and Johnny Thunders, while still trying to find my own sound. And then, for a bigger, more heavy sound, I’d run a Les Paul through one of my Marshalls.

So most parts were triple tracked?

Oh god, I mean, sometimes I would quadruple track. The setup on every song is a little different. There was some stuff where to get a really big tone, we’d just plug a guitar through a Boss Blues Driver and mess around with different echoes and delays. And on a couple of songs—like “Say Goodbye” and “Forever Now”—I took out a bow and just Jimmy Page-ed that motherf**ker. That was really fun.

Does your famous blue Fernandes make any appearances on the album?

No. But I do use Baby Blue on stage every night when we play the old stuff.

On the intro and breakdown to “Still Breathing,” you have a bluesy, half-dirty sound.

That was the neck pickup of a Fender Jazzmaster going through the Divided By 13. That part has this cool warbly sound I got by time-expanding the Pro Tools session so I could slow things down without changing the key. Then, when you play back what you’ve recorded at normal speed, it sounds warbly—like an old cassette tape.

Green Day has a very identifiable approach to low-fi vocal breaks. Is there a specific way you like record them?

To get that sound I’ll often just sing through a Shure SM58, and then tweak it later in Pro Tools. Or, I’ll sing through an amplifier. I love distortion on my vocals— even just a tiny bit to kind of make it a little more gritty. That’s probably because it’s the sound I remember from years ago, when you’d be doing shows with no P.A. and singing through someone’s guitar amp.

What would say is the biggest guitar learning experience you had?

What do you call it when you choke up on the pick to make your guitar squeal a little bit? A pinch harmonic? I learned that as a kid, and it just stuck with me. People might not realize it, but I often have my thumb way up on the pick when I play rhythm. I think it kind of adds a bit more punch when you’re playing the faster stuff, and you want some absolutely pulverizing guitar. I don’t think many players do that. I have a giant callous on my thumb from doing it.

How did you write “Ordinary World”?

I was on the set for a film I’m in—which is also called Ordinary World—when the director, Lee Kirk, told me he needed an intimate acoustic moment. So I dicked around with a couple of new things. I tried a few different keys, and I ended up with a capo at the 7th fret playing the cowboy-chord C shape. That was funny, because I soon realized at that position, I was in G again—just like on “(Good Riddance) Time of Your Life.” And then, I wrote the song. I finger-played it. I wouldn’t say I finger-picked it, necessarily, because it was a strum-y thing. You can get a really nice, chimey sound just by grazing the strings with your fingernails. The guitar was my Yairi steel-string. Almost every acoustic thing you hear from Green Day is that Yairi.

What does Green Day’s touring guitarist Jason White bring to the band’s stage show?

Jason is an awesome guitar player. He handles nearly all the solos on stage, which frees me up do other stuff and hold down the rhythm. He has a Fishman PowerBridge on his Gibson ES-335 to handle acoustic parts. He has also been playing “bow guitar” lately—which is incredible to watch.

Admit it, Billie, you like playing rhythm more than soloing—even though you played most of the solos on your records.

Yeah. I think of myself as basically a rhythm player. I like playing guitar solos, but, I don’t know—maybe I just have too much ADHD to focus on more than one animal at a time.

On The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon the other night I saw you playing a Les Paul Custom.

Yeah, I love that thing. This is the first time I’ve really played a Les Paul on tour and it has been fun.

Did you find it on the wall at your guitar shop, Broken Guitars?

No [laughs]. I got that from the Gibson Custom Shop. They’ve been really good to me. It’s a badass guitar.

What’s it like having a guitar shop?

It’s fun. It’s a total hangout where [store partner] Bill Schneider and I can do things. And I love that we’re in a neighborhood in Oakland where we’re able to provide a place for local musicians to hang out and talk guitars, drink coffee, and bullsh*t.

What’s the best part of owning your own recording studio, OTIS?

Honestly—besides the fact that it’s a great sounding room—one of my favorite things about OTIS is when I walk out the door, there’s life happening. There are people on the street and cool shops around. It’s just great.

Like you, I grew up in the Bay Area, and I’ve seen rents quintuple. How do you feel about the gentrification of our favorite cities?

The thing that disturbs me is watching artists and families get pushed out to Richmond, or even out to the Rodeo/Crockett area where I grew up. Yes, there is more cool stuff to do in Oakland now, but I hope Oakland doesn’t turn into San Francisco, where all these tech people own a bunch of empty houses that they keep to be their second or third home.

Who’s your favorite current guitar player?

I like bands more than I like individual guitar players. There’s a band called Beach Slang that’s really good. And I also like White Reaper.

What is your favorite onstage moment of your career?

One of my favorite shows ever was when we played Emirates Stadium in London a few years ago. I was watching the crowd as we were playing, and everyone was pogoing in unison. It looked like a giant flock of birds. That’s the only way I can describe it.

And your worst onstage moment?

That would probably be in Tucson, Arizona. We were playing this big place, and we didn’t have backup guitars. Mike and I both broke strings on the same song, and we had just one guitar tech. So, there we were, with 10,000 people looking at us, waiting for us to change our f**king strings [laughs].

Do you have any advice for my 19-yearold student at Musicians Institute, Carlos, who wants to do what you do?

Just be fearless and play. Don’t be afraid to be exceptional at what you do.

Engineer Chris Dugan on Tracking Revolution Radio

If you like the way Revolution Radio sounds, don’t just credit the record’s producer, Billie Joe Armstrong, or its worldclass mix engineer, Andrew Scheps (Metallica, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Adele). Remember to also credit the guy who captured every sound on the album, Green Day’s Grammy-winning engineer, Chris Dugan. —JG

“We tracked Revolution Radio at OTIS, which is Billie Joe’s studio in Oakland, California,” says Dugan. “It’s a former live/work loft that Billie and an architect friend of his remodeled from the ground up. I helped some, too. We floated the floors throughout the entire place, and they built a live room, three isolation booths, and a control room, and soundproofed the hell out of it. They also put in an apartment/lounge upstairs.

“OTIS’ mixing desk is a Trident ATB, but while I did use it for playback, at least 80 percent of what we did was tracked through external gear. We recorded in Pro Tools at 88.2kHz or 96kHz, depending on the song, keeping the sample rates way up there so that we’ll have some room to make high-definition tracks someday. Lead guitars typically went through two mics—this AEA N22 ribbon mic I acquired recently and an AKG C414—placed side-by-side on the same speaker. Those two signals went through Neve 1073 preamps and then got summed down to one track in Pro Tools.

“I also blended signals from various room mics when we were doing certain guitar overdubs— especially when we were tracking little combo amps. OTIS’ live room is small in comparison to everything we’ve always used, so there’s more energy in there when things are extra loud. For instance, when Tré is playing his drum kit in that room, there’s so much movement and energy in the air that the room reacts wonderfully. I placed room mics in pairs everywhere. I even had pair of Neumann TLM 103s split between the hallway and the downstairs bathroom.

“For acoustic guitar parts, I mostly used the N22. ‘Ordinary World’ was done before I had that mic, though, so I think I used a [Neumann or Telefunken] U47 on that one.

“We did do some nutty stuff here and there on the record—like grabbing the bow from a violin that Billie had in the corner and playing guitar with it on ‘Outlaws’ and ‘Somewhere Now,’ and maybe a couple other things. That was inspired by Eddie Phillips’ guitar bowing on the Creation song ‘Making Time’ from 1966, and also, of course, by Jimmy Page. That was fun, but Billie Joe’s best quality as a producer is keeping us wrangled and making sure we don’t get too extravagant with things. He’s great at steadying the ship. Everything was working so well that soon the M.O. just became, ‘Let’s not f**k this up.’”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Whether he’s interviewing great guitarists for Guitar Player magazine or on his respected podcast, No Guitar Is Safe – “The guitar show where guitar heroes plug in” – Jude Gold has been a passionate guitar journalist since 2001, when he became a full-time Guitar Player staff editor. In 2012, Jude became lead guitarist for iconic rock band Jefferson Starship, yet still has, in his role as Los Angeles Editor, continued to contribute regularly to all things Guitar Player. Watch Jude play guitar here.

"Why can't we have more Django Reinhardts going, 'F*** everybody. I'll turn up when I feel like turning up'?" Happy birthday to Ritchie Blackmore. The guitar legend looks back on his career in an interview from our December 1996 issue

"Get off the stage!" The time Carlos Santana picked a fight with Kiss bassist Gene Simmons and caused one of the guitar world's strangest feuds