How George Harrison Made the Epic Concert for Bangladesh Happen with a Little Help From His Friends

In the summer of 1971, Harrison corralled his musical friends to answer the call for humanitarian aid to Bangladesh. Two of his closest companions nearly left him hanging.

Fifty years ago, Bangladesh was in the midst of a humanitarian crisis. Millions of refugees in what was formerly East Pakistan were fleeing genocidal massacres and rape in the Bangladesh War of Independence, as well as lingering devastation from the 1970 Bhola cyclone, the deadliest tropical cyclone ever recorded, that left at least half a million dead in its wake.

The people were starving, but their plight was largely unknown in the West. Ravi Shankar knew he had to do something to bring attention and aid to the country. The famed Indian sitarist reached out to his friend George Harrison and asked him to do what only a famous former Beatle could do: Bring musicians and fans together to help end the disaster.

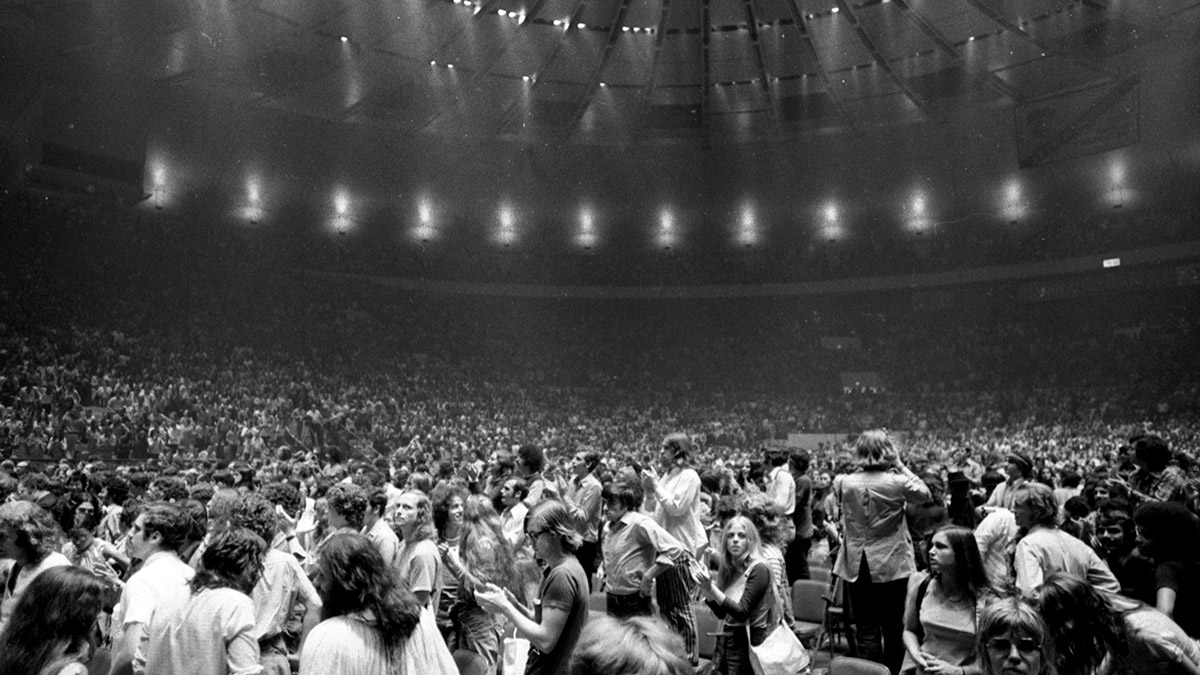

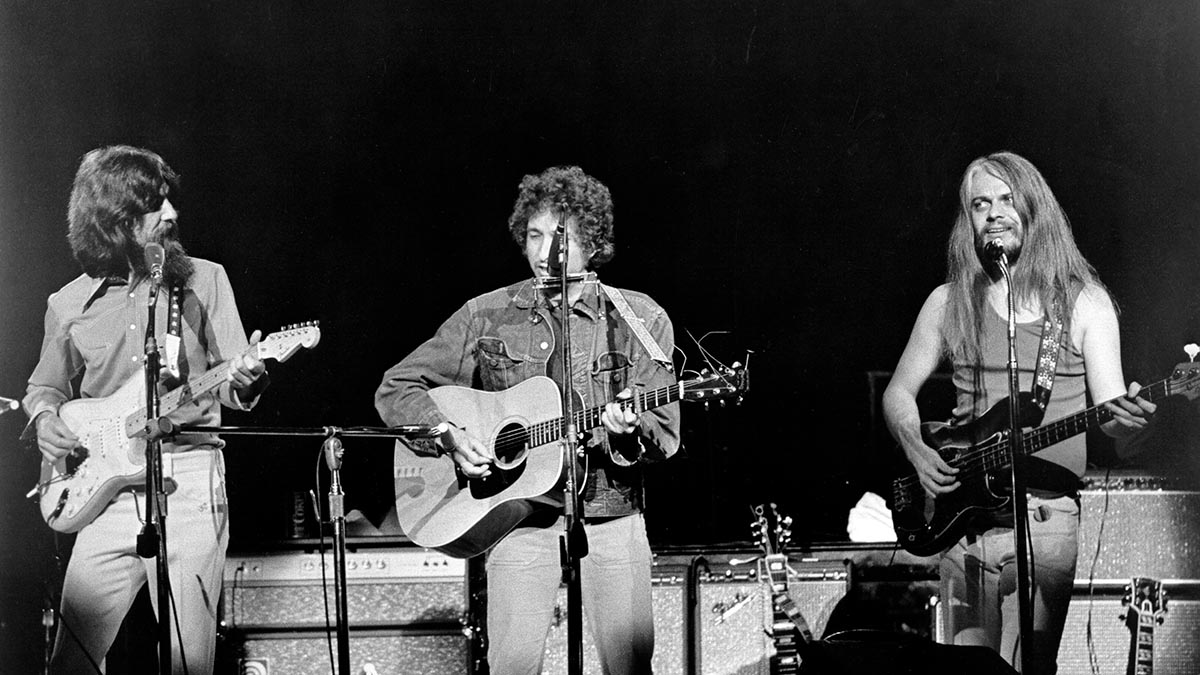

What Harrison and Shankar achieved was a massive benefit concert that was the first of its kind. Held 50 years ago this summer, on August 1, the Concert for Bangladesh gathered rock and roll’s royalty in New York City for a pair of shows to raise money for – and awareness of – the humanitarian crisis unfolding halfway around the globe.

In a matter of weeks, Harrison managed to secure participation from such luminaries as his fellow former Beatle Ringo Starr, keyboardist Billy Preston, pianist and guitarist Leon Russell, bassist and longtime Beatle friend Klaus Voormann, studio guitar ace Jesse Ed Davis, Zappa collaborator Don Preston, the up-and-coming band Badfinger, and a number of other musicians and singers.

Together with Shankar and his fellow musicians, they performed a pair of sold-out concerts at Madison Square Garden, including a 2:30 p.m. matinee and 8:00 p.m. show.

The concerts drew 40,000 people and raised $250,000 for UNICEF, while the 1971 triple live album and 1972 documentary of the show eventually raised millions more. Even before the concert took place, Harrison had released his single “Bangla Desh” on the Beatles’ Apple label. The track, which detailed the plight of the Bangladeshi people, was put into heavy rotation in the lead-up to the shows, bringing the single to number 23 on the Billboard charts.

Harrison’s achievement would prove nothing short of a miracle. No rock and roll musician had attempted anything like it before, and no template existed for a show of this size and with guests of such stature.

The Concert for Bangladesh would cement the notion of a moral imperative for rock and rollers to do their part for those in need, as it laid the groundwork for the charity concerts that followed in the 1980s and beyond, including Live Aid and Farm Aid.

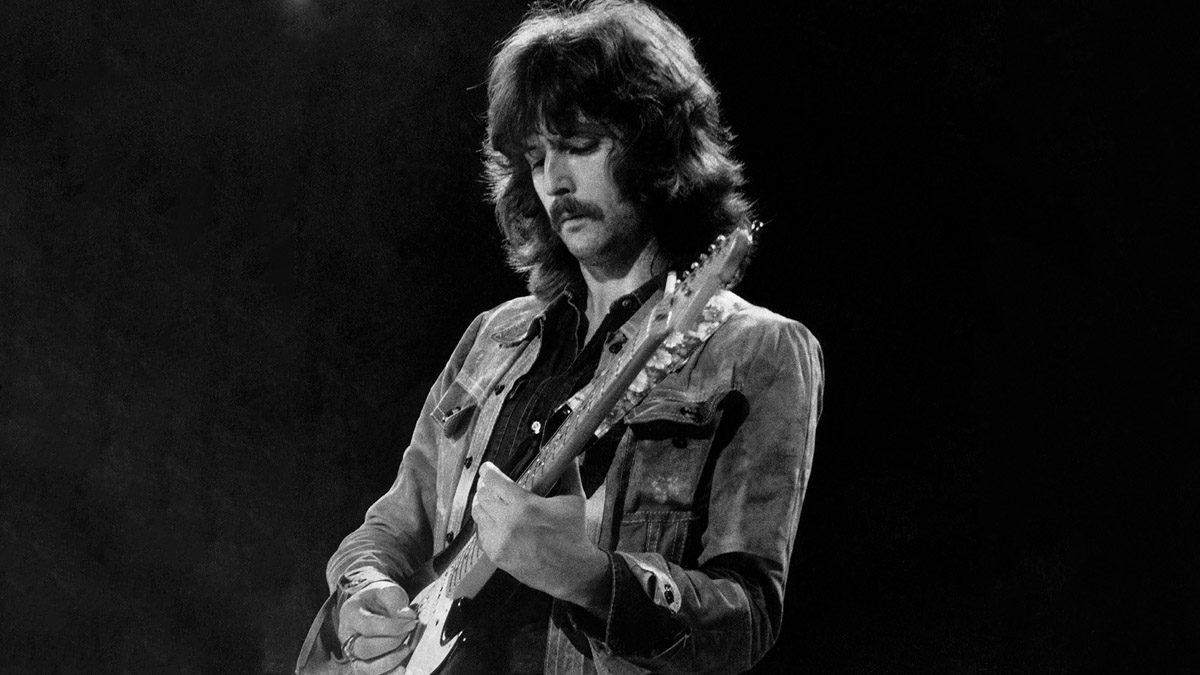

Yet in the days before the show, Harrison was filled with doubt and insecurity. He hadn’t performed in front of a large crowd since the Beatles’ final tour, in 1966. But those wild shows were scripted affairs lasting roughly 30 minutes, with the band’s performance entirely secondary to the sight of the four mop tops shaking their bodies onstage.

Concerts had grown up in the intervening years and become listening experiences. And this particularly lengthy two-show stint – from the planning to the staging to the musicians, many of whom were flying in from the U.K., India, and various parts of the U.S. – was all on Harrison’s shoulders. Many performers, like Leon Russell, had canceled other appearances, at great expense, to participate.

As Harrison noted, “Nobody’s getting paid.” He was so focused on the concert’s purpose that he seemed to forget its sheer star power, and openly fretted that nobody would care enough to buy tickets.

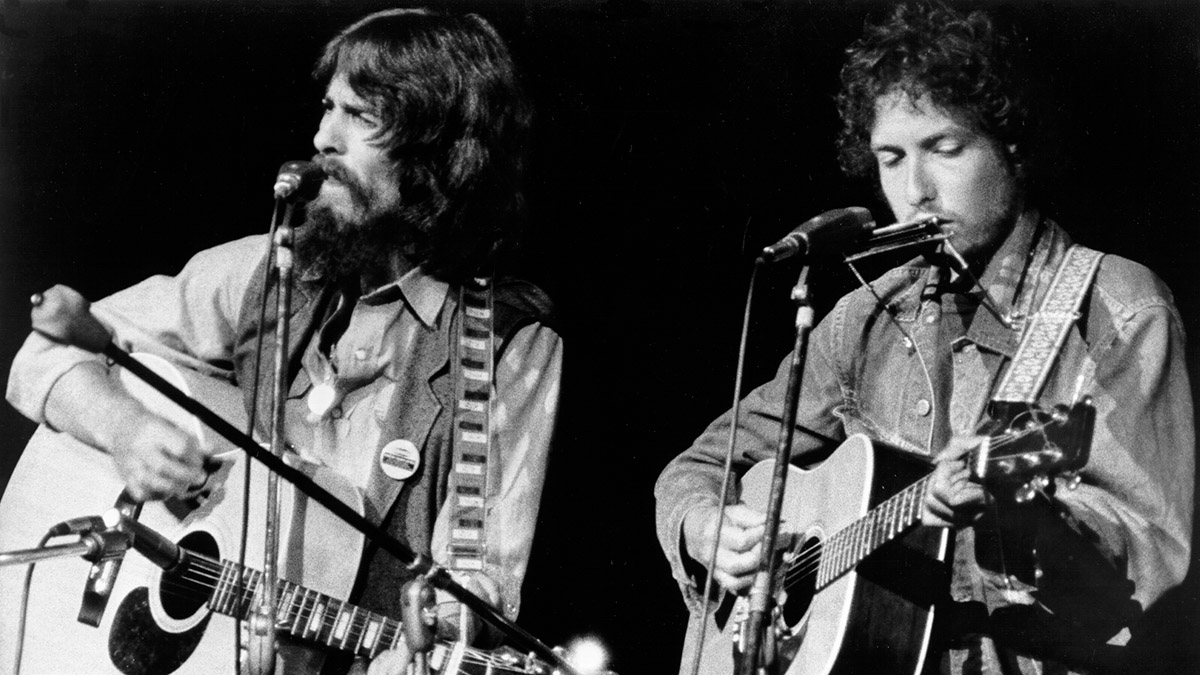

Remarkably, among all his friends in the show, Harrison would be kept waiting, wondering and worrying over the attendance of two who were his closest: Eric Clapton and Bob Dylan. At the time, Clapton was deep into the throes of heroin addiction and uncertain of his ability to perform. Dylan, meanwhile, was a recluse, having given his last live performance in 1969, at the Isle of Wight.

But Harrison was among the best-connected people in rock at the time. As the August 1 concert date approached and Clapton increasingly looked like a no-show, he turned for help to another friend: Peter Frampton.

Harrison had known the guitarist, then in Humble Pie, for a couple of years. Frampton tracked guitars on singer Doris Troy’s self-titled album, produced by Harrison for the Beatles’ Apple Records, and he played acoustic guitar on All Things Must Pass, Harrison’s third solo record.

As it happened, Frampton and Humble Pie were touring in the U.S. that summer and spending time in New York City, where they were mixing their 1971 live breakthrough, Performance: Rockin’ the Fillmore, recorded the previous May 28 and 29.

“On the weekends, we’d fly off to perform, opening the bill for many different artists, and on weekdays we’d be at Electric Lady Studios in New York with Eddie Kramer, mixing the Rockin’ the Fillmore album,” Frampton recalled to Guitar Player.

“I knew I was going to see George’s shows, and I asked if he needed me to play guitar, but they were overbooked with guitarists. So I wished him all the best with the show and told him I’d come see it.”

Unexpectedly, Frampton found himself invited to dine with Harrison and his wife, Patti, while they were in Manhattan. “Afterwards, we went back to the Pierre [Hotel], and he invited me up to their suite,” Frampton explains.

“There were two electrics sitting by the window, and maybe one or two little amps. George asked if I wanted to play some guitar, and I said, ‘Yeah, sure,’ trying to keep my excitement under control.

“And without a word, he just started running through the songs they were going to do. My mind started going 14,000 miles an hour. I couldn’t understand why we were doing this if the guitar positions for the concert were filled. We must’ve played six to 10 songs, and he was checking me out to see if I was up to speed, which, of course, I was. How can you not be when it comes to the Beatles’ songs?”

In the days afterward, Frampton flew south to play a couple of shows with Humble Pie. Back in New York City, the behind-the-scenes drama escalated as the August 1 concert date arrived. Frampton returned on the day of the show.

The last thing I wanted to be was a stand-in for Eric Clapton

Peter Frampton

“I’d missed the first one, but I planned to go to the second, and so I picked up my tickets and backstage pass,” he says. “I watched the entire show, and at the end, I made my way to the side of the stage. Terry Doran [Harrison’s personal assistant] saw me, and his eyes got really big. He said, ‘Where have you been?’ I said, ‘What do you mean? I’ve been on the road.’ And he said, ‘Yeah, but we had no way of getting hold of you!’”

Confused, Frampton explained that no one had asked for his number, adding that Harrison knew he would see him following the show. “And Terry says, ‘Well, George wants to speak to you!’ So as he takes me backstage, he pulls me right into Bob Dylan, who gives me the ‘I could slice your head off with the back of my hand’ kind of look.”

Meeting up with Harrison, Frampton says he learned that Clapton had been bedridden while in New York City and unable to make any rehearsals.

“This was during his heavy drug phase,” Frampton says. “Whether he had some or was trying to give them up, I don’t know. But when he wasn’t able to rehearse, they tried to get hold of me, because they wanted me there – just in case. I asked George and Terry, ‘You mean you wanted me to play?’ And they said, ‘Yeah.’”

In the end, a cameraman from the film crew provided Clapton with methadone, making him well enough to perform both shows. “I’m glad that Eric was able to play somehow, since a lot of people would’ve been very disappointed if he didn’t, especially George,” Frampton says.

“The last thing I wanted to be was a stand-in for Eric Clapton. I would’ve done it if George had gotten hold of me and the situation was more dire. But I’ll never know how dire it actually was.”

According to Joey Molland, it was a closer call than Frampton knew. At the time, Molland was a member of the Welsh rock group Badfinger, one of Apple Records’ most prominent signings, thanks to their early hit “Come and Get It,” written and produced by Paul McCartney.

The group had performed on Harrison’s All Things Must Pass, and Harrison had taken over producing the group for their 1971 album, Straight Up, in late May 1971. But as he found himself sidelined by the Bangladesh benefit, the sessions stalled and he invited the group to perform at the concerts.

Molland, bassist Tom Evans, and guitarist Pete Ham performed on acoustic guitars, while Badfinger drummer Mike Gibbins played percussion. In addition, Ham assisted Harrison on his captivating performance of “Here Comes the Sun.”

“We went to New York 10 days before the concerts,” Molland explains. “George had arranged for rhythm section rehearsals at the Steinway store in downtown Manhattan, where they had a big room upstairs.

"It was a lot of fun, going over the intros, outros, and the sequencing of events within songs. I think we rehearsed Monday through Friday, and on the Saturday we went to the Garden to do a couple of hours of dress rehearsal.”

Molland confirms Clapton had been a no-show. But while Frampton believes the guitarist was already in New York City, Molland contends he was still in England.

“I believe George sent a car for Clapton, and each day he stayed in his house,” he says.

“I wasn’t privy to what was happening to him, and I don’t like to speculate, but he was going through something. But on Friday night, two nights before the show, he got on the plane in London, was in New York Saturday morning and was at the rehearsal in the afternoon. He had his parts together. I didn’t see him screw up, but mind you, I was really concerned about my own guitar parts.”

The dress rehearsal was the first time the members of the main band played together, though second drummer Jim Keltner had yet to show up. “Otherwise, the whole band was there, including Ringo Starr, Leon Russell, the Hollywood Horns and Jim Horn, and the backup singers with Don Nix,” Molland says.

Given that Clapton played a Fender Stratocaster on All Things Must Pass the previous year, Molland expected him to show up with one or two. “But yes, Eric Clapton showed up, and he was playing a Gibson Byrdland, one of those beautiful, blonde Chuck Berry guitars, which we thought was a bit odd,” he says. “But everybody was enjoying it.”

Just as the dress rehearsal wrapped up, Bob Dylan made his appearance, much to everyone’s surprise. “There had been rumors that ‘someone’ might come up, and we thought it’d be John [Lennon],” Molland explains. “But we had finished the rehearsal and were sitting in the auditorium, waiting for our cars, when Bob Dylan walked onstage with his harmonica stand and a small acoustic guitar, and started singing his songs for about 40 minutes.

“George, Ringo, and Leon ran down to the stage, and they played a few songs all together before they put together that part of the set for the show. It was great to see them working through vocal harmonies.”

Reportedly, Dylan was still harboring doubts about performing at such a large event, much to Harrison’s frustration. ”Look, it’s not my scene, either,” Harrison told him. “At least you’ve played on your own in front of a crowd before. I’ve never done that.” Even after the dress rehearsal, Dylan remained noncommittal, giving Harrison one more thing to worry about.

“I’m sure George was nervous,” Molland says. “He hadn’t played in front of an audience for a few years, and he had never played these songs live. Plus, the whole event was on his shoulders. He wasn’t sure if anybody was going to come.”

But of course they did. Fans descended on Madison Square Garden to buy up tickets, and the two shows quickly sold out. Given the number of guitarists in the show, it’s difficult to track every guitar used over the two concerts. Harrison played a stripped Fender Stratocaster of unknown provenance, as well as a pair of Harptone acoustics: an L-6NC and an L-12NC.

While Clapton played the Byrdland for the first show, he switched to his “Brownie” Stratocaster for the second concert. Don Preston arrived with his Gibson ’58 Explorer, a model that particularly excited Molland. “It’s just an incredible guitar,” he enthuses. “It always astounded me how good they sound, and how light they were.”

Molland has a clear recollection of the acoustics he and his Badfinger bandmates played. “All of them were late-’60’s models, and they were used when we got them. I played a Gibson J-50, as I enjoyed the smoother tone.

"Tommy had brought his D-41, but he never played it; George had his Harptones and said he might be able to get some for us, but that never came together, so Tommy borrowed George’s 12-string. Pete played a Martin D-28. And there were no acoustic amps or pickups back then, so we were all mic’d up, and we sat next to the horn section. I was worried people wouldn’t be able to hear the acoustic guitars. But it turned out okay, because you can hear us on the record.

“We were a little bit nervous about playing right and doing the job well, so it wasn’t fun for us, but it was really exciting: the place being sold out, people losing their minds and doing something for the good of it all.”

For Molland, one of the show’s highlights was organist Billy Preston’s impromptu dance during the band’s performance of his hit “That’s the Way God Planned It.”

“He started to dance across the stage toward us, rolling his arms and skittling his legs,” the guitarist recalls. “And we were sitting on stools playing acoustic guitars, thinking, My God, he’s gonna run into us! But both shows went off as planned.”

In the end, Dylan showed up. Following his performance of “Here Comes the Sun” with Pete Ham, Harrison picked up his Fender Stratocaster and reviewed the set list taped to its body to see what was next: “Bob?” it read. Harrison looked around anxiously. To his relief, Dylan was making his way to the stage, his 1963 Martin D-28 strapped on and a harmonica in the holder around his neck.

“He had his guitar on and his shades,” Harrison recalled. “He was sort of coming on, coming [pumps his arms and shoulders]… It was only at that moment that I knew for sure he was going to do it.” Harrison turned to the microphone to deliver the biggest applause line of the show: “I’d like to bring on a friend of us all, Mr. Bob Dylan!”

The Concert for Bangladesh was a triumph of ingenuity and musical talent, a spur-of-the-moment project that launched a new concept in concerts. Its benefits, however, would take years to reach the afflicted country. Those involved in the concert’s planning, including Apple manager Allen Klein, neglected to register the event for tax-exempt status in the U.S. and U.K., with the result that millions in tax dollars were held up for years.

But ultimately, the album and film would raise and deliver an estimated $45 million, and Harrison would pass along the wisdom he gained from the experience to Bob Geldof when he launched Live Aid, ensuring that event’s estimated £50 million found its way to victims of the Ethiopian famine. Harrison’s groundbreaking humanitarian work continues to inspire musicians around the world.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

"Why can't we have more Django Reinhardts going, 'F*** everybody. I'll turn up when I feel like turning up'?" Happy birthday to Ritchie Blackmore. The guitar legend looks back on his career in an interview from our December 1996 issue

"Get off the stage!" The time Carlos Santana picked a fight with Kiss bassist Gene Simmons and caused one of the guitar world's strangest feuds