“Like Neil Young Said, It’s Better to Burn out Than to Fade Away”: Gary Rossington Remained “The Last Rebel” Whose Presence Through Lynyrd Skynyrd’s Many Incarnations Was Essential

When Gary Rossington died, Lynyrd Skynyrd lost its last link to the band’s hell-raising origins. In this tribute, Johnny Van Zant and Rickey Medlocke recall his music, legacy and southern spirit

Back in 1993, Johnny Van Zant wrote “The Last Rebel,” a song for Lynyrd Skynyrd’s album of the same name. Its lyrics paint a picture of a defiant but tired soldier left on a battlefield: “You can see the shadow of his past written in his eyes... His friends are all gone.” Coming from a band that sang about “Sweet Home Alabama” – and did so with a decidedly southern accent – the impetus seemed obvious. But in fact, “the boy with his old guitar” who’s “got a dream that will never die” was actually someone closer to home for the singer.

“That one was about Gary,” Van Zant explains. Gary Rossington, Skynyrd’s mainstay guitarist, was the only founding member to be part of the group’s entire active career, until his death on March 5 at the age of 71 after long-term health issues, primarily heart-related, took their toll.

“I just started thinking about Gary being the last of the three who started this band,” continues Van Zant, who’s been Skynyrd’s frontman since 1987, filling the shoes of his brother Ronnie, who was killed in the October 1977 plane crash that put the band in dry dock for a decade. “We made it into him being a soldier. That was my thought with that song: He was one of the soldiers, and he fought through to the end. He was the last rebel, man. Forever.”

There’s no question that, at the time of his death, Rossington was the heart and soul of Lynyrd Skynyrd, even if his health prevented him from joining the band onstage regularly during the past couple of years. He began playing with Ronnie Van Zant and late Skynyrd guitarist Allen Collins during the mid ’60s and was the force behind Skynyrd’s resumption back in 1987. He saw the group through its 14 studio albums and numerous live sets and compilations. Rossington was writing up until the end, too, penning material for a proposed farewell album that, so far, is represented only by the aptly named 2020 single “Last of the Street Survivors.”

“I didn’t mean to be the last original, or the last man standing, but here it is,” Rossington said back in 2018, when Skynyrd announced the album and a planned two-year farewell tour that was scuttled by the COVID-19 pandemic. But that role resonated with Rossington, and he felt a purpose in playing the music he’d created with Van Zant, Collins and other deceased bandmates such as bassist-turned-third-guitarist Ed King, drummer Bob Burns, bassists Larry Junstrom and Leon Wilkeson, keyboardist Billy Powell and guitarist Steve Gaines and his sister/backup vocalist Cassie Gaines, who were also killed in the 1977 plane crash.

“It’s heavy,” Rossington acknowledged at the time. “I’m just happy to still be doing it, going out and spreading the word about Skynyrd and all the great songs, and talking about Ronnie and Allen and Steve Gaines, and Leon and Billy and all the guys we lost, just keeping them alive. And every time we play, I feel the other guys’ spirits with us, and they’re helping and making sure everything is all right. So I feel like there’s a whole bunch of people up on that stage.”

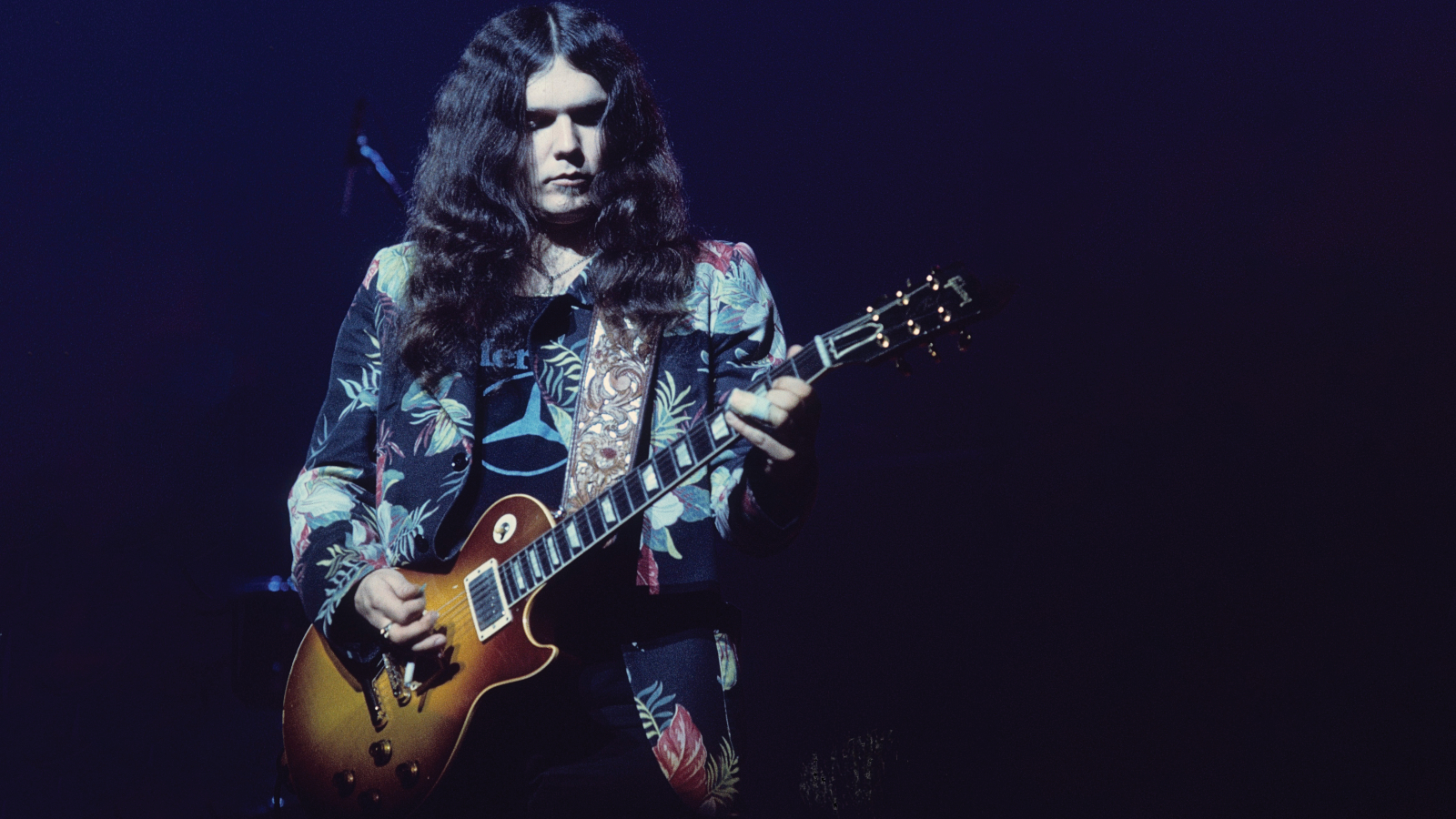

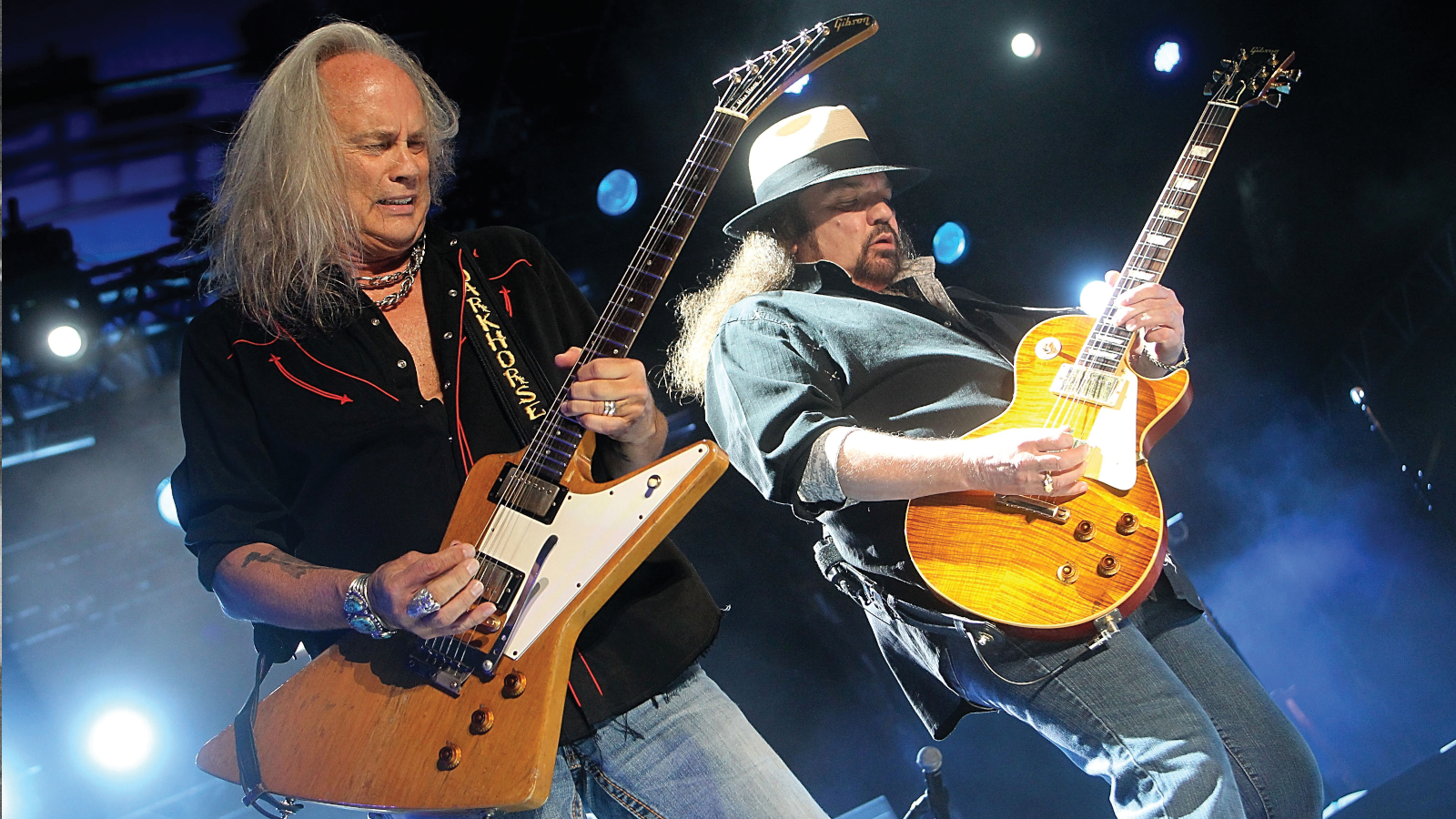

Through the group’s many incarnations, Rossington’s presence was the essential tie to the band’s legacy, a black-clad, hat-wearing, Les Paul-slinging embodiment of credibility, speaking softly but hitting hard with his guitar, whether it was the fire of “Free Bird” or the aching gentleness of “Simple Man.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

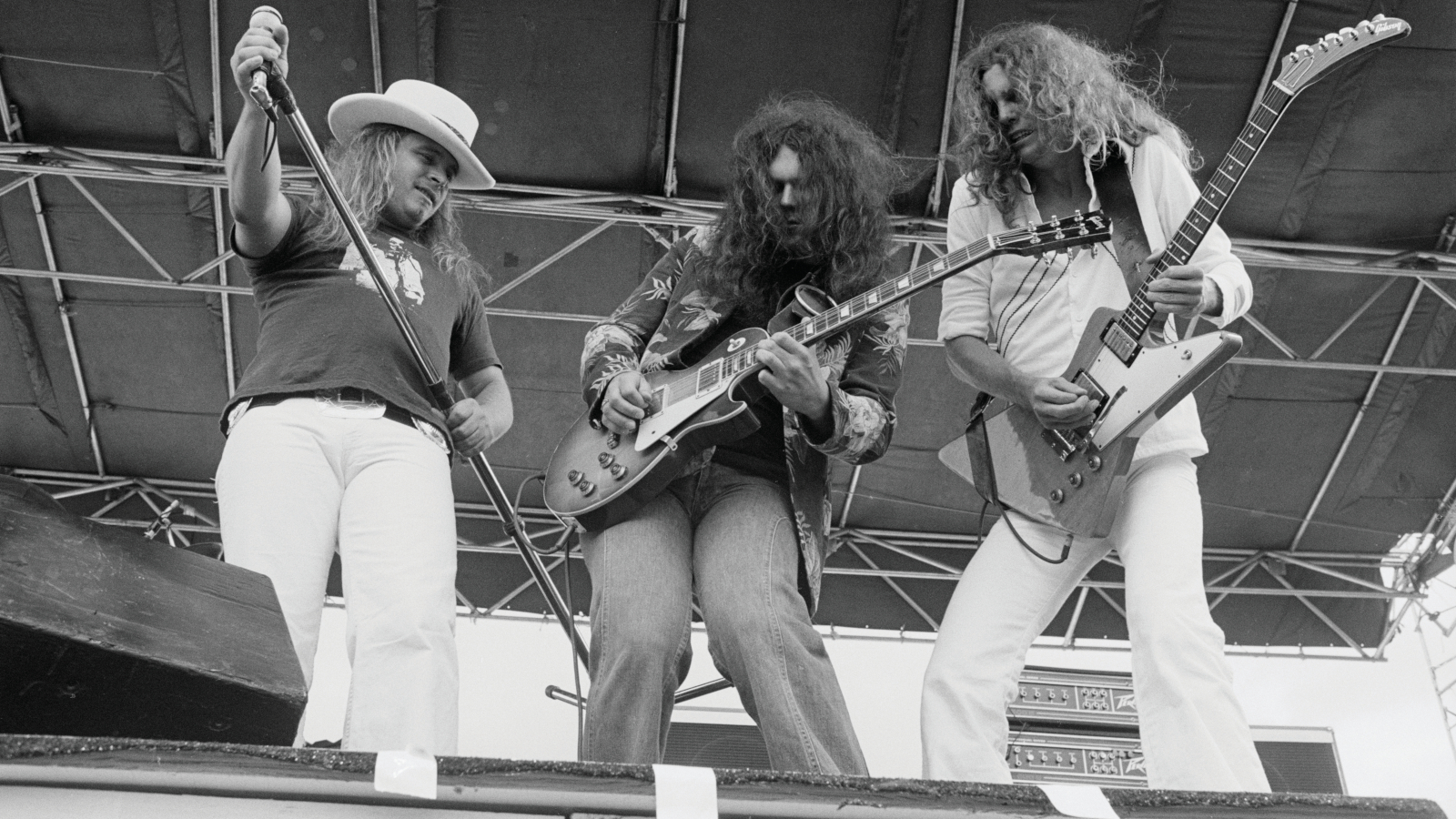

“Gary Rossington played a very integral part in the creation of all of that,” notes Rickey Medlocke, the Blackfoot founder who played drums in Skynyrd circa 1970-’71 and rejoined as a guitarist in 1996. “His presence and his talent was a very important part of the music and that band. If you go back into the early years when I first joined the band, just watching those two guys, Gary and Allen, work on those parts and the dual leads that would become great songs later on... It was Gary’s sound and the tone and his connection with Ronnie in writing the songs that brought it all together.”

It was Gary’s sound and the tone and his connection with Ronnie in writing the songs that brought it all together

Rickey Medlocke

Adds Van Zant, “I always thought Gary played like he acted. He was a shy guy, kinda quiet, and he had that mysterious quality, playing guitar with the long, drawn-out sustain. And the riffs he came up with and his leads were always like his personality. You could really hear the guy in his playing.”

Born in Jacksonville, Rossington found his first passion in baseball, playing sandlot and in organized leagues, with aspirations to one day join the New York Yankees. He actually met Van Zant and Burns through the sport, playing on different teams. They became interested in music as teens, however, and wound up playing the Rolling Stones’ then-current single “Time Is on My Side” in the carport of Burns’ home, the same day Van Zant had struck the drummer with a pitched ball.

“The music was changing us,” recalled Rossington, who was raised by his single mother in West Jacksonville after his father died, shortly after Gary was born. She fronted the eight dollars for his first guitar, a Sears and Roebuck Silvertone, and he later named a prized 1959 Les Paul “Berniece” after her. (It now resides in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum in Cleveland.) “We still loved baseball, but we were connecting with the Stones, the Beatles – what we were hearing on the radio.”

And, he acknowledged with a laugh, “The girls were starting to like the rock stars better than the jocks. So there was that.”

With bassist Larry Junstrom, they formed the Noble Five, which became the One Percent before taking the name Lynyrd Skynyrd from Leonard Skinner, the strict gym teacher at Robert E. Lee High School who suspended Rossington for having long hair. Van Zant’s father, Lacy, cajoled administrators into letting the maverick aspiring rock star back into school, although Rossington ultimately dropped out to concentrate on the band.

Jacksonville had a vibrant music scene, recalls Medlocke, who got his music jones from his grandfather Paul “Shorty” Medlocke, a touring bluegrass musician. There was a preponderance of teen clubs – the Woodstock Youth Center, the Good Shepherd, the Riverside Women’s Club – as well as the Comic Book, which was all ages until midnight, when the kids were sent home and the liquor came out.

Paul Kossoff was so huge for Gary. He had a 1959 Gibson Les Paul. Well, Gary ended up getting a ‘59 Les Paul

Rickey Medlocke

“Ronnie’s mom and dad would come out to my granddad’s dances, so that’s how I knew Ronnie – and then got to know Gary,” Medlocke says. “We all played the teen centers, and we intermingled with each other. You were able to trade conversations back and forth of who you were into, who you liked at the time, what record was out that was best. With Gary, it was all about the music. Nothing else. That’s how we all bonded.”

Exerting a particular influence on Rossington at the time was Paul Kossoff, then playing lead guitar with Free. “We saw them live once,” he remembered. “We saw them play right up close, and they just blew our minds. That’s when we really got serious about playing and working hard. We worked every day and night after that, so they helped us make it and were such an influence on us. And I just love ’em to death.”

Medlocke, meanwhile, had a front-row seat to that impact. “Paul Kossoff was so huge for Gary,” he says. “He had a 1959 Gibson Les Paul. Well, Gary ended up getting a ‘59 Les Paul. And then out of that Gary created his own thing that was a very integral part of Lynyrd Skynyrd: the sound.”

There were other sources of course, including the then-burgeoning Allman Brothers Band that was planting a flag for the South in rock and roll in a different manner than the likes of Little Richard and Sun Records’ Tennessee gang – Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis and Carl Perkins.

But Rossington claimed that the idea of southern rock as a genre was not intentional on Skynyrd’s part. “We were just rock and roll, y’know?” he explained. “We were labeled southern rock through writers. ’Cause all of a sudden a lot of southern bands were doing great – us and the Allmans, Charlie [Daniels], Wet Willie, Marshall Tucker, the Atlanta Rhythm Section – it was a whole new scene taking off down here, and they needed to give it a name. I was proud to be from the South. We always were. But we didn’t think about the South as part of the sound. It’s just who we were.”

The southern heritage did come with baggage, though. “We showed the Confederate flag when we started out,” Rossington acknowledges. “We didn’t mean any kind of harm or hard feelings or anything racist. It was just ’cause we were a southern band, and we were just really proud of that, and [the flag] was more a part of the culture down there. But when it started to upset people we understood, so we stopped using it.”

I was proud to be from the South. We always were. But we didn’t think about the South as part of the sound. It’s just who we were

Gary Rossington

Skynyrd were one of Jacksonville’s most popular bands by 1970, when they headed to Quinvy Studios in Sheffield, Alabama, to record early demos, including a first crack at “Free Bird.” Later, the group checked into the famed Muscle Shoals Sound Studios with Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section guitarist Jimmy Johnson and bassist David Hood, the studio’s co-founders, who Medlocke says “really showed us what the difference between recording and playing live was all about. We really cut our teeth in there.” The band members were also still finding their way as songwriters. “We used a lot of D - C - G progressions,” Rossington told Guitar World in 1993. “It’s all about what you do with them.”

It was at Muscle Shoals, in fact, that “Free Bird” began to take flight. After some experimentation Collins found the chords for “the slow part,” as Rossington calls the song’s first half, which is how Skynyrd began to play the song in the clubs. The lyrics were inspired by a conversation Collins had with his wife, which was ultimately fleshed out by Ronnie Van Zant.

“Ronnie could never quite come up with a melody, but Allen kept playing it over and over again, and it finally clicked with Ronnie,” remembers Medlocke, who was playing drums during the sessions. “It was a magic moment.” Except, he explains, “It was actually a love song and they played it like that, and it never quite went over.”

Van Zant came up with the idea to extend the end, according to Rossington, who created the chord pattern that he and Collins began soloing over. It was the frontman who urged them to keep stretching it out.

“To us it was just a love song, and it had a lot of great guitar playing at the end for me and Allen to do,” Rossington said years later. “But it was really just a simple love song he wrote. We didn’t know it would do anything like it did, but it was mind-blowing. And it just hit.”

In 1972, the group’s onstage ferocity hooked Al Kooper, a music impresario from New York City who had played with Bob Dylan – most famously as the organist on “Like a Rolling Stone” – and founded the Blues Project and Blood, Sweat & Tears, among other groups. “I heard them play for six nights in a row at a bar [Funochio’s in Atlanta],” recalled Kooper, who at the time had launched a label called Sounds of the South. “And by the sixth night, I offered to sign them.”

Al Kooper produced Skynyrd’s first three albums, all of which hit the Top 30 on the 'Billboard' 200 and ultimately went Platinum, or better

Skynyrd was aware of Kooper’s reputation and seduced by his stories. ”We were Hendrix freaks, and [Kooper] had played with him [on Electric Ladyland], so we wanted to hear everything we could about him,” Rossington said. Despite a lot of head-banging between their sensibilities, Kooper produced Skynyrd’s first three albums, all of which hit the Top 30 on the Billboard 200 and ultimately went Platinum, or better.

“He had a lot of ideas, but we just kinda had a band and we had all the songs written,” Rossington said. “We argued a lot, because he wanted to put in different things and different techniques or keyboard parts. We locked horns with him a few times. Ronnie and him would argue about things, and me and Allen Collins would write our own leads and have it down pat what we thought was best for the song, and [Kooper] would say, ‘No, go out and play it different’ or ‘Do this.’

“I remember on ‘Sweet Home Alabama,’ Ed King did the solo and the song is in D, but Ed played it in the key of G, which worked but sounds a little different. And him and Al Kooper fought for days about that. [Kooper] hated that solo and Ed liked it, and they fought over that for a while. But it all worked out, and turns out it’s a great solo.”

There was also some drama around “Simple Man” from the band’s 1973 debut, (Pronounced ’Lĕh-’nérd ’Skin-’nérd), which Rossington wrote with Van Zant and considered one of his all-time Skynyrd favorites. “[Kooper] didn’t want us to do that song. He didn’t think it went anywhere and didn’t say much,” Rossington said. “But we loved it. So he had to go to New York on a quick weekend one time, and we recorded ‘Simple Man’ without him there. And when he got back he heard it and went, ‘Oh, wow, that’s great. Let’s do it,’ and he played organ on it, so it worked out in the end.”

“I really enjoyed the time I spent with them and the music that they made,” says Kooper, who will join Skynyrd in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame this year. “And I think they were grateful. They had been with a couple of people before me and it didn’t work out, and it worked out this time.”

After those first three albums, however, Skynyrd hit a creative malaise due to a combination of booze, drugs and exhaustion from heavy touring, including opening for the Who. Ed King departed in 1975. That left Rossington and Collins to make Gimme Back My Bullets, Skynyrd’s lowest-selling album to date, as a two-man unit. But the addition of Gaines, who was suggested by his sister, fired things back up just in time for the group’s landmark 1976 live album, One More From the Road.

'One More From the Road' was a Top 10, triple-Platinum smash, with an 11-and-a-half-minute version of “Free Bird” that eclipsed its studio predecessor

“Me and Allen were just getting by with it and doing all right with it, but we missed that third guitarist for double leads and more power-packed rhythms and stuff,” Rossington said. Skynyrd actually had several songs written quickly for a new studio album, but, Rossington noted, “We were due to do an album, and our new producer, Tommy Dowd, had [engineered] Live Cream and Wheels of Fire and a bunch of other [concert records], so it seemed like a live album was a good idea.

“We had just gotten Steve a month or two before, so he was really new and hadn’t played that much with us, and some of the songs we hadn’t gotten around to teaching him yet.” Rossington laughed at the memory. “He’d just jam along or play what he knew of ’em, and it was great and we all loved him for that. It was nerve-wracking, but it worked out better than we could’ve hoped.”

Coming in the wake of live album hits by Kiss, Peter Frampton and Bob Seger, One More From the Road was a Top 10, triple-Platinum smash, with an 11-and-a-half-minute version of “Free Bird” that eclipsed its studio predecessor, and was even a Top 40 hit.

Skynyrd took that momentum into 1977’s Street Survivors, arguably the band’s best studio effort and its highest-charting title, reaching number five. The free bird was flying high when the Convair CV-240 airplane transporting the band to a show in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, crashed near Gillsburg, Mississippi, killing Van Zant, Steve and Cassie Gaines, assistant tour manager Dean Kilpatrick and the two pilots. The rest of the band and crew suffered severe injuries. As far as Rossington was concerned, “we were through. There was no way to still be Lynyrd Skynyrd without Ronnie and Steve and Cassie. It just wouldn’t be right.”

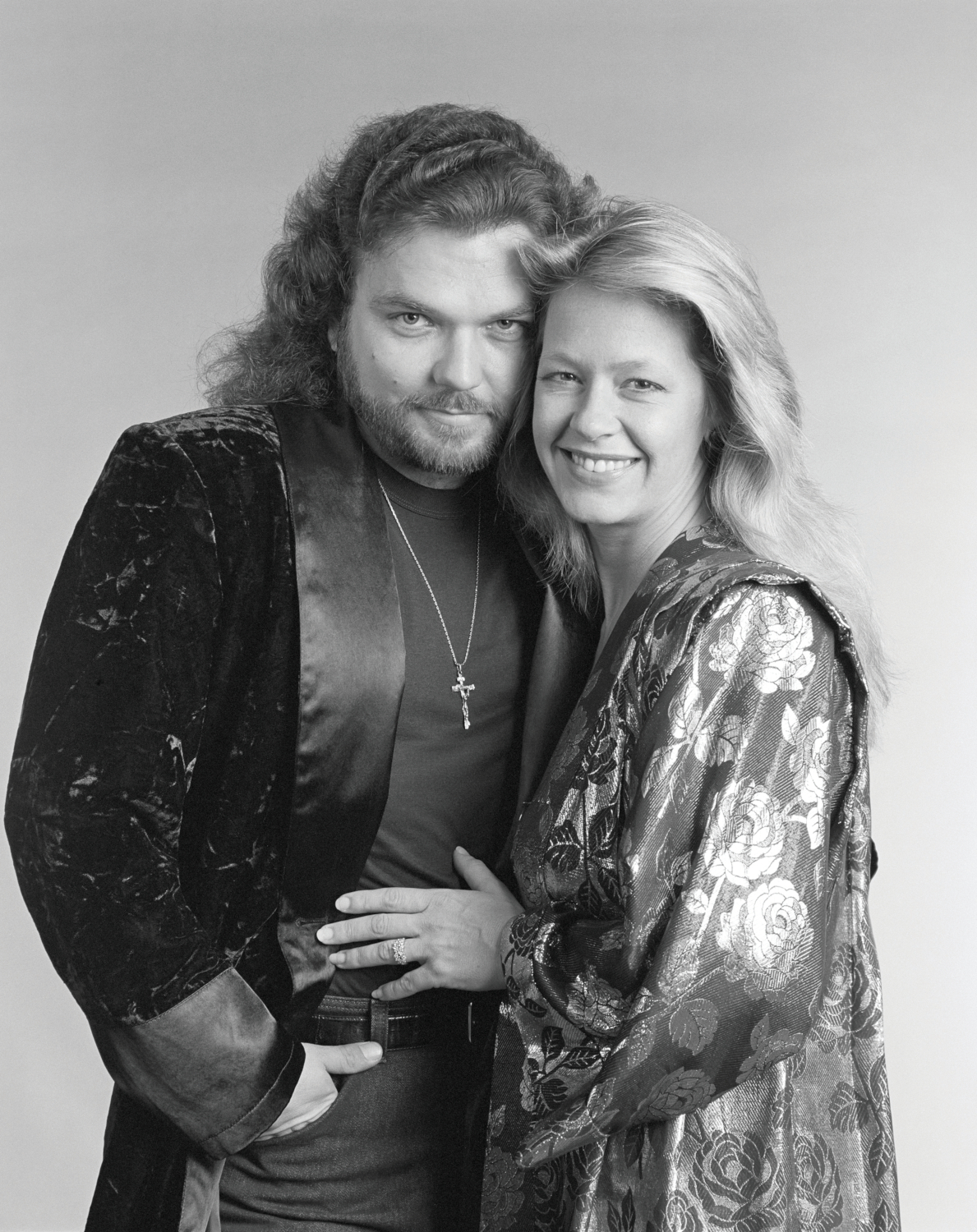

After a bit of time, Rossington and Collins launched the Rossington Collins Band, which released two albums and disbanded in 1982. Rossington and his wife, Dale Krantz-Rossington, started the Rossington Band, which released another two albums, but the guitarist gradually warmed to the idea of putting Skynyrd back together.

“The last thing we did together as a group was have a plane crash. We’d like to go out on a better note than that,” Rossington explained in 1987, as he, Powell, Wilkeson, Ed King and drummer Artimus Pyle regrouped for a tour, with Johnny Van Zant singing. Collins had been paralyzed in a 1986 car crash but served as a co-musical director for the troupe. The trek was designed as a one-off tribute tour but quickly became a full-scale resumption that led to nine more studio albums and some rather characteristically heavy road work.

I never dreamed it would go on this long

Gary Rossington

“I never dreamed it would go on this long,” Rossington said 20 years later. “We really thought it was over after [the crash]. But we got a lot of fan mail and stuff saying, ‘Please keep going, we love having you back.’ And there were so many promoters saying they were getting a lot of requests. We decided that if we could write together, get something happening that was good and new, then maybe we could go on.”

Van Zant, who put aside a new solo record deal to take part in that initial tour, says now, “I think there was unfinished business there for Gary and the other guys. Of course it was very scary, and very intimidating. The first thing I told them was, ‘Listen, I can’t be Ronnie. I’m gonna be me,’ and they said that’s what they wanted. And it worked out.”

Lynyrd Skynyrd 1991 was the band’s first studio album since Street Survivors and the first of a streak of new music that’s so far run through 2012’s Last of a Dyin’ Breed. Four years after that, Rossington and his wife made their own album, Take It on Faith, their first outing outside of Skynyrd since the Rossington Band’s second album, in 1988. Produced by David Z, the set featured an all-star lineup of players, including the late Richie Hayward of Little Feat fame, Delbert McClinton, Bekka Bramlett, Double Trouble keyboardist Reese Winans and others, as well as songs co-written by ZZ Top’s Billy Gibbons.

“It was just spontaneous,” Rossington said shortly before its release. “It only took a couple of weeks of recordings and a few overdubs and we were done. I got to use my Dobro on a song, and then I actually took a few different guitars up there to play in Nashville. I didn’t use my Les Paul a lot – maybe on half of it. I tried to get some different kinds of sounds, to sound different than Skynyrd. It was such a fun thing to do.”

Rossington had already begun having heart problems by that time, and some Skynyrd dates had to be canceled during the previous year after he suffered a heart attack. But the guitarist had no interest in succumbing to those health issues and dialing down. “I just take every day on faith,” he said. “I guess when it’s my time, I’m ready. I’d rather be playing and living life up than… Like Neil Young said, it’s better to burn out than to fade away. I’d rather just burn out in the next 10 years than sit in a rocking chair and look at the trees blowing in the wind. It’s just in my blood, y’know?

“I’m just an old guitar player, and we’ve spent our whole lives and the 10,000 hours of working to understand how to play and do it. So I think once you’ve got something going for yourself, you should keep it up and keep your craft going. When you retire, what’s next? I like to fish, but how much of that can you do, right? So I want to keep doing what I do now.”

I think once you’ve got something going for yourself, you should keep it up and keep your craft going

Gary Rossington

Krantz-Rossington agreed. ”After Gary’s [2015] problem, we really had a serious talk about just letting it go for now and being happy to be alive,” she says. “But after a few days, he was just miserable, and he said to me, ‘I would much rather go out kickin’ it than sitting here in my chair.’ And that was the last time we talked about it. After that we just decided to ask for God’s mercy and do it till we drop.”

“Gary was a trouper, man,” Medlocke adds. “The guy was a tough individual.” Even when Rossington was off the road, he and Van Zant consulted with him as an active part of the band’s leadership, reporting in from the road, going over set lists and other arrangements. Van Zant’s usual salutation was, “Captain Kirk? Spock calling,” while Medlocke would discuss their shared passion for The Andy Griffith Show and Gunsmoke reruns. “He was still part of the band, even if he wasn’t there,” Van Zant says.

Both Van Zant and Rossington himself had said there would be no Skynyrd without the guitarist, with Rossington predicting, “I think it’s gonna have to end when I’m gone – not that I’m so great, but because of all the legalities and stuff.” But less than a month after his passing, the band, along with Krantz-Rossington, issued a statement that Skynyrd would indeed continue, with the approval of all other interested parties.

“I’ve been here over 27 years now,” Medlocke, says. “I’ve been here to see quite a few members move on, pass away, and it doesn’t get any easier. We had been at a crossroads several times about whether to go on or whatever, and we had always maintained that it wasn’t about each individual or anything like that. It was about the music that was created by those guys – Ronnie, Gary, Allen. So we made the decision to carry on with the music because, bottom line, the music is what is important.”

Van Zant confesses that “my heart was so broken that I couldn’t imagine going on,” but other voices intervened. “Talking to the estates and various people and talking to fans, I’m like, ‘Oh God, yeah, they’re counting on me to carry this on.’ Y’know, what kept me going was calling [Rossington] and having these conversations. He was my cheerleader. So now I’m gonna have to remember his voice to keep my spirits up and keep me going.”

What lies ahead for Skynyrd is open-ended

What lies ahead for Skynyrd is open-ended. Van Zant and Medlocke talk about finishing an album, which would include other songs Rossington co-wrote. But mostly they want to honor their last rebel as well as those that went before him. And they flip a big middle finger to those who would say they can’t.

“People have beat us up over the years: ‘Ah, you guys ain’t nothin’ but a freakin’ tribute band,’ and ‘blah, blah, blah,’” Medlocke says. “There’s a lot of Lynyrd Skynyrd tribute bands out there, but none of them holds it as dear to their hearts as the guys who have been there as long as we have. We have the history; I played on the first [recording] sessions. We just know that we have to portray the music with the integrity and the sound and the love as close as we can to when it was originally created. It’s only right.”

Gary Graff is an award-winning Detroit-based music journalist and author who writes for a variety of print, online and broadcast outlets. He has written and collaborated on books about Alice Cooper, Neil Young, Bob Seger, Bruce Springsteen and Rock 'n' Roll Myths. He's also the founding editor of the award-winning MusicHound Essential Album Guide series and of the new 501 Essential Albums series. Graff is also a co-founder and co-producer of the annual Detroit Music Awards.