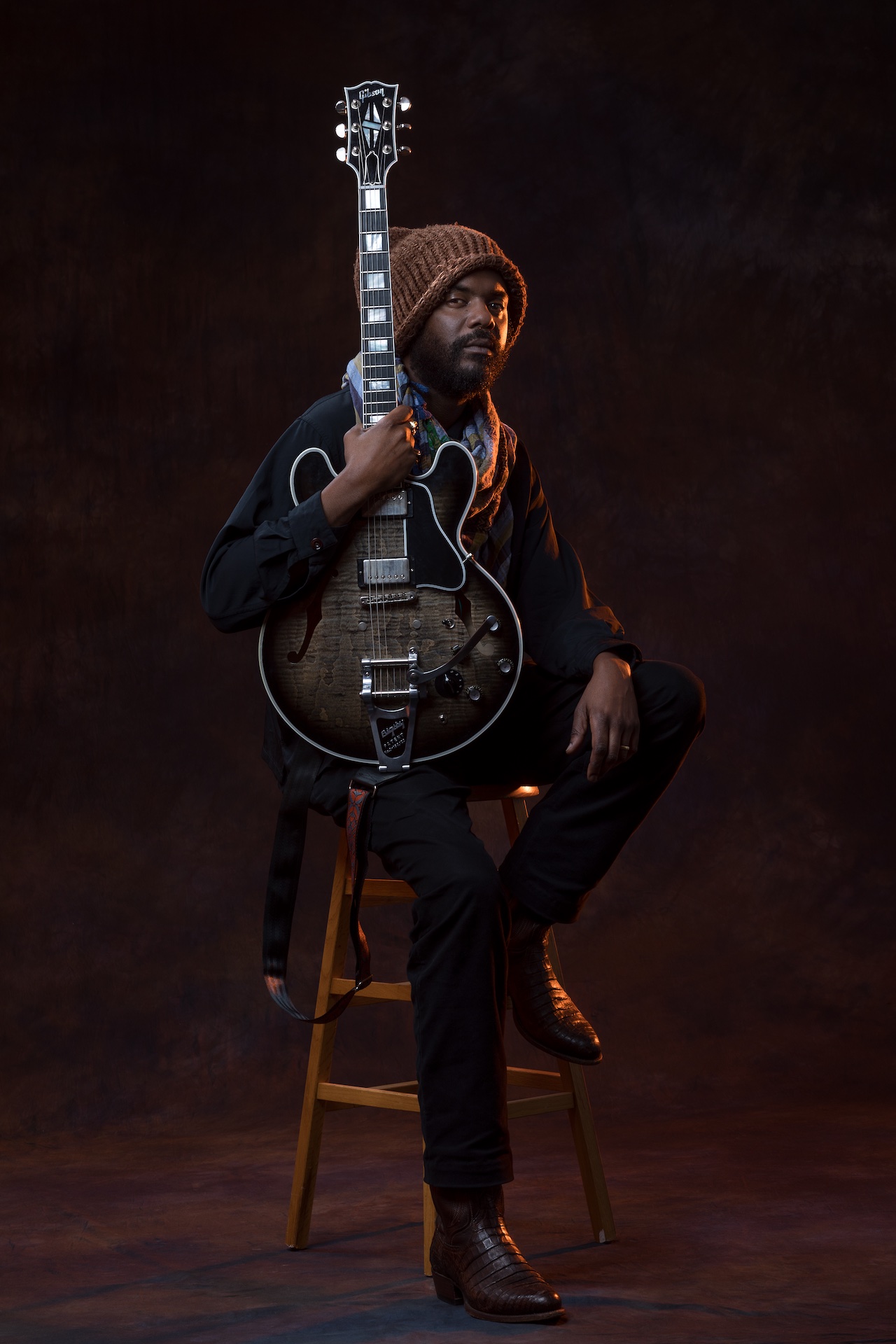

“I remember seeing my posters everywhere. It was like, ‘Gary Clark Jr. – the new Hendrix.’ I was like, ‘Man, you’re not even giving me a chance to be anything but a blues or rock-star guitar player’”: Gary Clark Jr. never asked to be a guitar savior

JPEG RAW is Gary Clark Jr.’s first post-pandemic album, but its origins date back to the 2020 lockdown, when the guitarist, like every other musician on the planet, was forced to scrap his tour plans and await a return to normal life.

“It was a weird time,” he says. “The world was shut down, and I didn’t know what I was going to do. I was hiding out in L.A., just waiting for kid number three to come. There wasn’t much else to do, so I started making beats and playing guitar. Somehow I found myself listening to things that I hadn’t paid much attention to growing up.”

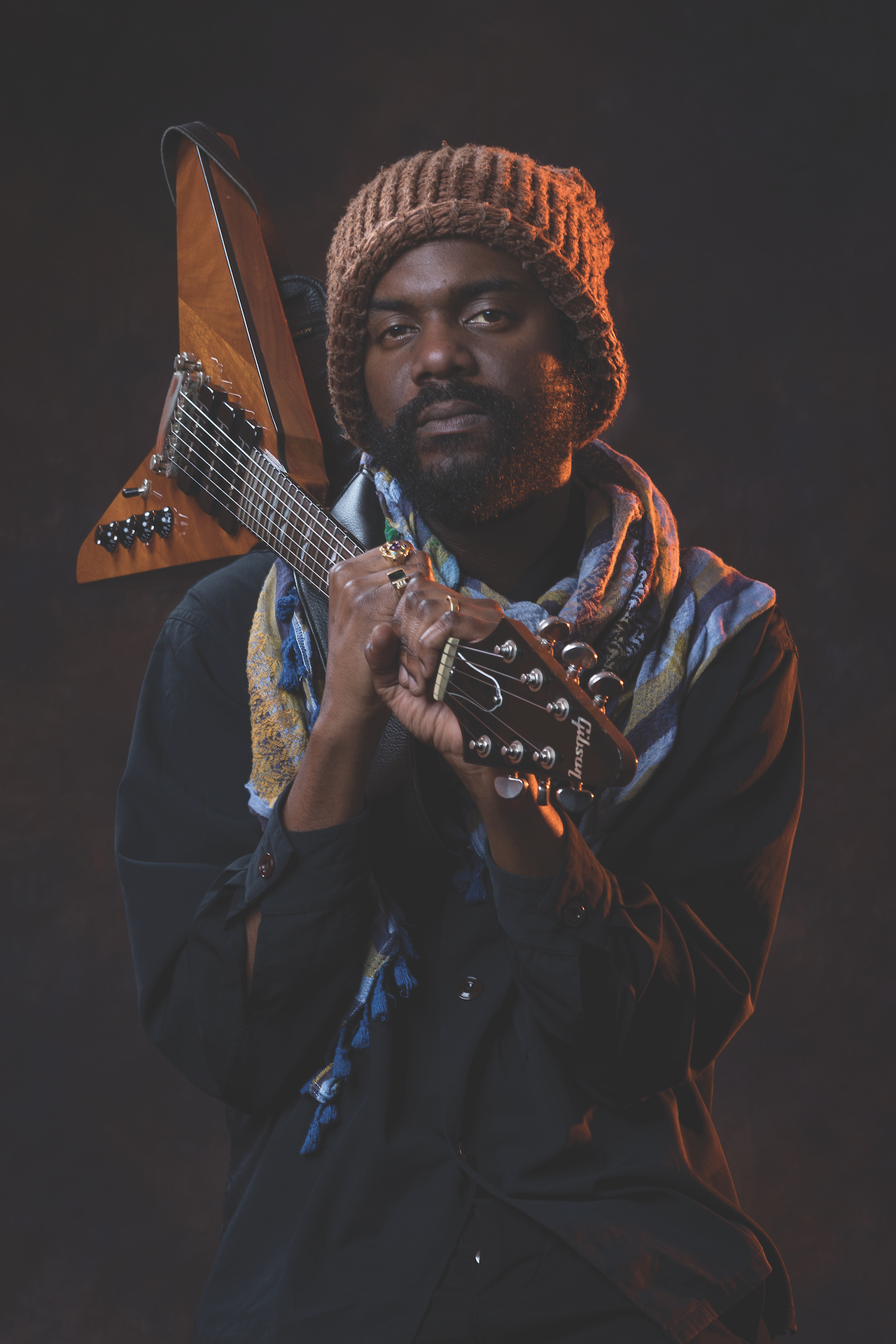

In the same way that he immersed himself in rock and the blues as a young guitarist, Clark dove head-first into the world of 1990s guitar virtuosos. As he explains, “When I started on guitar, my friend Eve taught me about the blues, and I learned about rock from my friend Gilberto. He introduced me to guys like Slash and the whole G3 thing – Steve Vai, Joe Satriani, and Eric Johnson. During the pandemic, I was bored and I thought, ‘What if I studied that?’ I basically turned into a teenager again. I locked myself in a room and started shredding guitar.”

Armed with a Floyd Rose–equipped Ibanez, Clark cranked up the distortion and woodshedded triads and “funky weird scales” while watching videos of Steve Vai’s For the Love of God and Eric Johnson’s Cliffs of Dover. And he had a blast.

“I was doing whatever I wanted,” he says. “I wasn’t worried about being Gary Clark Jr., or whoever everybody thinks they know. I was just being the guy I know.”

By now, listeners should know better than to ever even try to pigeonhole Clark. Ever since he made his debut in 2012 with the album Blak and Blu, he’s freely mixed elements of blues, R&B, rock, and hip-hop on records that featured his bold and expressive guitar playing.

His last album, 2019’s This Land, took his stylistic influences even further, adding splashes of reggae, psychedelia, and punk to the menu. JPEG RAW (it’s an acronym for Jealousy, Pride, Ego, Greed, Rules, Alter Ego, and Worlds) is his most diverse album yet. At times, it’s like a collision of moods and styles, sounds and textures. And it’s impossible to predict from one song to the next where he’s headed.

Maktub (named after the Arabic word meaning “it is written”) is a chaotic rocker that comes on hard and heavy with a hyper-distorted riff that just won’t quit. The album’s title track blends ’70s soul, a New Jack swing groove and tasty blues guitar lines, but in the blink of an eye it’s overtaken by a bruising indie rock stomp that recalls the White Stripes in full bloom.

Tumult is the name of the game on the tough-as-nails funk rocker This Is Who We Are, a collaboration between Clark and alt-pop/electronic artist Naala, on which the guitarist tears out a wildcat, fuzzed-out solo.

As a palate cleanser, To the End of the Earth is a delicious, unexpected surprise. Luxuriously clean guitar lines and buttery chords wrap around Clark’s velvety vocals on a jazz-pop love ballad that stands out like a beam of light. And at a minute and half, it’s over much too soon. Having guested on Stevie Wonder’s 2020 single Where Is Our Love Song, Clark rejoins the music icon on the funky gem What About the Children, contributing co-lead vocals, squawking wah lines, and spirited soloing.

Another legend, George Clinton, turns up on the spacey, hallucinogenic Funk Witch U, which sees the guitarist’s dirty tone mangled and magnified into something otherworldly. The nine-minute album closer, Habits, is a musical Cuisinart featuring lush pop, waves of electronic rhythms and symphonic sounds, Townshend-like acoustic strumming, and elegant soloing on both electric and nylon-string guitars. Fearless, adventurous, filled with moments of beauty and madness (and mad beauty), it’s a stunning statement from an artist operating at the peak of his powers.

Working with longtime co-producer Jacob Sciba, Clark brought both new and returning faces into the studio, among them his right-hand rhythm guitar ace Zapata, keyboardists John Deas and Elijah Ford, bassists Mike Elizondo and Alex Peterson, and drummer JJ Johnson, with an eye toward group collaboration.

“I was really into getting a different perspective this time,” he says. “I liked how everybody worked with one another and how we came together to create something. It was exciting. It was like we were making a movie. I could get into different characters while singing, evoking emotions that I’d never done before.”

Despite all of his stylistic leaps, there is something about the public’s perception of him that dogs Clark. As he points out, “I was presented as a blues guitarist. But I never said that.”

Undoubtedly, his backstory made for compelling reading – how, as a young player, he jammed with the likes of Jimmie Vaughan and Hubert Sumlin at the famed Austin blues club Antone’s, and how he was picked by Eric Clapton to perform at Madison Square Garden at the 2010 Crossroads Guitar Festival. With these kinds of bona fides, it’s no wonder that critics leapt over themselves to crown him as a new blues messiah. The tag has held through the years, and he’s hoping JPEG RAW will set the record straight once and for all.

“I remember my first tour of Australia and seeing my posters plastered everywhere,” he says. “It was cool but also devastating, because it was like ‘Gary Clark Jr. – the new Hendrix.’ I was like, ‘Fuck, man. You’re not even giving me a chance to be anything but a blues guy or a rock-star guitar player.’

“My records have been presented as blues, but I’ve never made a traditional blues album. I’ve always had hip-hop influences and made beats. I’ve always had rock influences. I’ve played all kinds of music since I was a kid. I’ve had trumpets and saxophones and violins and bagpipes, just because I’m interested in music. I don’t care about genre. I like how music makes me feel.”

I know you aren’t married to genres, but you do mix them up in interesting ways. The way you treat ’70s soul on the new album feels both forward-thinking and nostalgic. As you get older, do you find you reach for nostalgia?

“I don’t know if I’m necessarily reaching for nostalgia as I get older. I think of all that music from the ’70s – the soul and R&B and funk – it was the soundtrack to my childhood. It was there from the time I was born to when I moved out and I took my parents’ records with me. I just loved that stuff so much. It’s always felt relevant. I’m a big hip-hop fan, and that music is ingrained in me. It’s followed me my whole life.”

I got made fun of because I walked in proud with an Ibanez Blazer and a solid-state Crate amp. I was showing up to blues clubs with that, and they were like, ‘What the hell are you doing?’

You mentioned how you got into shredding during the pandemic. How do you feel it affected your approach on the album?

“Instead of having these internal thoughts – ‘What if I did this? What if I did that?’ – I just did things unapologetically. During the pandemic, everything was shut down. I didn’t know what the world was going to be like or if music was over. I just did things for me and because I liked it. Same with the guys in the band – we didn’t know what was going to happen.”

Was shred guitar frowned upon when you were young and playing in blues clubs?

“Oh, sure. When I was coming up in Austin, you wanted to be part of the cool club. There was this one club that was very strict about what they would allow.”

Shredders weren’t welcome, right?

“Not at all. I got made fun of because I walked in proud with an Ibanez Blazer and a solid-state Crate amp. I was showing up to blues clubs with that, and they were like, ‘What the hell are you doing?’ But you know, at a certain point, you can’t please everybody.”

Your lyrical content frequently dips into social commentary. It was all over your last album, and you’re definitely making a statement with songs like This Is Who We Are. Do you ever hear from fans who trot out that standard line, ‘Shut up and play your guitar’?

“Oh yeah, absolutely. I mean, some of my favorite artists are the ones who encouraged me to do this: Marvin Gaye, Bob Marley and the Wailers, Stevie Wonder, Sly and the Family Stone... I come from that thing of putting something in your music to make you feel it. Jimi Hendrix’s Machine Gun blew my mind. I was like, ‘Oh, shit, you can do that?’ Psychedelic badass music that tells a story, or sometimes it’s just an observation of things that aren’t necessarily so pretty in life – I’m there.”

Are you generally a fast writer? Do tunes come to you easily, or do you have to labor over them?

“To the End of the Earth came quick, but all the other songs took a long time to write. Musically, there’s no problem. The band comes in, we get an idea and we knock it out. Got it. The musical process is fun and easy, and that keeps the energy going.

“My lyrical writing thing wasn’t happening. I like to be around people. I like to be out in the world and observe. In the middle of the pandemic, I wasn’t watching things happen, and I was like, ‘What do I write about?’ I had to go search internally for things that were real to me.

“I also had conversations with the guys in the band, and I talked to Jacob Sciba. We’d talk about what was going on in our lives, and it was like, ‘All right, this isn’t just observational mode; this is digesting-what’s-going-on-in-our-lives mode’ – which is quite scary. Writing has never been quite that personal to me. I kind of find ways to broaden the story so it can be more relatable. This one is really direct.”

More than on your previous albums, the predominant guitar sound on this record is maximum overdrive and totally rude. [Clark laughs] Did you have a go-to guitar and amp combination for that sound?

“I had a Gibson 355 that I used. At Arlyn Studios, they’ve got a 100-watt Cesar Diaz amp that I’m trying to buy, but it’s a no-go on that. I used that quite a bit. I can’t take all the credit for some of the sounds you’re referring to. That’s my guy Zapata. We’ve been playing music together since high school. He studies tones and sounds. The guy is dialed in. He can make a guitar sound like anything.”

I take it that you two collaborate a lot on guitar parts while writing and recording?

“Yeah, sure. On this record, the guys in the band were kind of a new crew. We were writing stuff together and bringing ideas in to jam on. Zapata’s role was writing riffs and bringing big tones to kind of balance out my more subtle jazz influences. We wanted loud riffs. On Hyperwave, his guitar sounds like an electric piano. Whatever he does sonically, it just feels right. I’m like, ‘Cool. That’s the flavor to put on this.’”

How do you respond to each other as players? Is there a push and pull?

“If he’s doing long legato stuff, I’m doing comps and short rhythmic hits. If he’s holding down the comps, I’m doing the riff or I’m playing a solo. It’s like a push and pull, sort of a dance. But not just with him – it’s with everybody.”

The massive, earth-moving fuzz riffs on Hearts on Retrograde…

“That’s all Zapata. He came up with the riff and was like, ‘What do you think?’ J.J. played the drums, Elijah was on the bass, and I was like, ‘Yeah, let’s see what we can do with that.’ I was running the board, recording everything. I learned how to work with Pro Tools. They laid that one down on the floor and I added my parts afterward.”

I think if a certain song calls for a longer solo, that’s fine. But I don’t think putting a minute-and-a-half guitar solo into a song is going to do it any justice

Talk to me about how you collaborated with Stevie Wonder on What About the Children.

“Yeah, he hit me up and sent me a demo: ‘I got a song for you.’ It was him mumbling some words and playing a harmonium. He was like, ‘You think we can do something?’ I said, ‘I’m in the studio with the guys right now. You want me to try and put something together?’ So we did and I sent it to him. I asked him if he would sing on it with me. And not only did he sing on it, he sang his ass off!” [laughs]

You play a great solo on the song’s outro.

“Thanks, but honestly, he sang over the outro and I was telling everybody to take my guitar part out. It felt unnecessary, but I guess it’s kind of cool. I was like, Stevie Wonder is singing and mashing on the gas like that – I need to get out of the way. But we kept it in.”

The song has a bit of a Boogie on Reggae Woman feel to it.

“Oh, absolutely.”

The wah guitar licks you play throughout sound so perfect with Stevie’s voice. Did he encourage that kind of approach?

“You know, I just went for that. It was an instinctual thing, and it felt right. I didn’t even really think twice about it.”

I brought up your use of distortion, but To the End of the Earth is quite different. What lovely clean tones on those chords and lines! And your singing is gorgeous. The song evokes a spirit of early 1960s jazz-pop.

“Oh, thanks. I was hanging with Mike Elizondo. He’s such an amazing producer and musician. He played me [1963’s] John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman, and I fell in love with that sound. I started singing like that around the house, and I picked up the guitar and kept at it. I was just playing. I don’t feel schooled in any one style, but I’m definitely influenced by Wes Montgomery and Grant Green. All those guys – Charlie Christian, Lonnie Johnson...”

Guitar and amp-wise, what are you using on that track?

“That’s my 355 and a Fender Vibro-King. I didn’t use pedals. I just reverbed it up.”

I’ve got to be honest – I’ve got a beef with you about that track.

“Uh-oh!”

I think people have gotten used to hearing my songs and just waiting for a guitar solo. I’ll tell you, I kind of get bored with myself playing guitar solos

It’s a fantastic song, beautifully rendered, but it cuts out after a minute and a half. What the hell, man?

“[laughs] That was all I had. I would’ve done more, but I just didn’t have it.”

There are a couple of great solos on This Is Who We Are: one in the middle of the song, and another in the ride-out. Overall, there are fewer guitar solos than on your previous records.

“I just wanted to present music, and I think people have gotten used to hearing my songs and just waiting for a guitar solo. I’ll tell you, I kind of get bored with myself playing guitar solos. It just seems… I don’t know… a little gross.”

“Gross”? But you’re the guy who was just woodshedding to the G3 guys!

“[laughs] I think if a certain song calls for a longer solo, that’s fine. But I don’t think putting a minute-and-a-half guitar solo into a song is going to do it any justice. To me, it’s not going to serve the song. I mean, it might.

“Now, the thing is, the record is the record, but the fun thing about being with a band and playing live is those things can change and we can play that guitar solo for 10 minutes if we want. You know what I mean? But when I’m presenting a song on a record, it’s like, boom, there it is – a little taste. You can’t give everybody everything all the time.”

I’ve never heard a guitarist describe playing solos as “gross.” That’s a new one.

“Let me clear that up. I didn’t say, and I didn’t intend to say, that all guitar solos are gross. I’m saying that the guitar solos I play feel gross to me. The kind of guitar playing that I love, love, love is really tasteful and intentional, and I found that the kind of guitar playing people love me to play is kind of raw and unhinged and off the rails. That’s cool. It’s fun to step on a fuzz pedal and play loud and wild, but I would never go back and listen to my guitar solos. I don’t enjoy that.

“Whereas guys like Eric Johnson, Steve Vai and Satriani, as wild as their playing is, it’s still a beautifully composed and disciplined presentation that evokes the same emotion as me. I think it hits people the same way. Me playing wild and fast like that isn’t the same thing at all.”

Is this a bit of an internal conflict for you? What you’re saying is, the kind of playing you really respond to isn’t necessarily what your fans want from you.

“When we first started going out, we were a three-piece, sometimes a four-piece with Zapata. We didn’t have that many songs, so we had to stretch ’em out: It was either sing the first verse again at the end, or stretch the guitar solo out, which is what I ended up doing.

“I’d keep playing because we were on our last song and we were at 39 minutes in the set – but we had to play for 45 minutes. It was cool and fun and it worked, but after awhile it’s like, ‘All right.’ I just got tired of myself. I was like, ‘This is gross.’ I stand on that.”

Well, on the new record you could have stretched To the End of the Earth out a bit more.

“[laughs] Yeah, I know. We’ll see what happens. Maybe that song is ‘to be continued.’”

Beyond the ES-355, what other guitars did you use on the album? I’m assuming your signature Casinos and SGs?

“I used a Casino on the song Triumph. For the riff and a lot of the loud, hard fuzzy stuff, I used an SG. I could turn it up and it wouldn’t scream back at me. When I was working at my home studio, I went from Casino to SG – they were all sitting there. But my main one was the 355. I might have used a 175. I can’t remember.”

A few years ago, you told me that you were resisting amp modeling. Have you reconsidered?

“I haven’t gone there yet. I’m a little bit scared of that; it’s just something new to learn and grab. I mean, I already know what a Fender Twin will do. I know what my guitars and pedals will do. If you think I’m stretching out and getting wild now, put one of those amp modeling units in front of me. It’s all over. [laughs]”

Aside from the Vibro-King, what other amps did you use?

“Just a Fender Princeton and the Cesar Diaz amp. It was pretty simple.”

I don’t care what it looks like. I don’t care who makes it. I just care what it sounds like. I can close my eyes, and I know when it’s right

How about effects? Any go-to pedals?

“I didn’t use anything consistently. I was just trying stuff, and I went through a bunch of things petty randomly. I didn’t keep notes or anything. I’d go to the music shop: ‘I need a fuzz pedal. I need a delay. What kind of reverbs do you have?’ I probably played a hundred different pedals on this thing. Every time I’d hang with Mike Elizondo, he’d look at my pedalboard and say, ‘Let’s try some other options.’ He’d go to his closet and pull out a bunch of stuff.

“I keep swapping out fuzzes and delays. I keep swapping out reverbs. I’m not settled yet. I thought I was, but during the process of recording I was trying to figure out why something that works in the studio doesn’t necessarily translate live. I want this record to translate live, but I also want my tone to be recognizable. I’m trying to find a balance here. We’ve been in rehearsal and I’m not yet satisfied.”

I’m a little surprised that you don’t have any fuzz boxes or delays that you use consistently.

“I don’t really pay attention to gear either that much. I don’t care what it looks like. I don’t care who makes it. I just care what it sounds like. I can close my eyes, and I know when it’s right. It’s a feel thing. My body reacts to a tone in a certain way. I’ve always been that way.”

- Gary Clark Jr.'s new album, JPEG Raw, can be streamed or purchased now.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

"Get off the stage!" The time Carlos Santana picked a fight with Kiss bassist Gene Simmons and caused one of the guitar world's strangest feuds

“It’s a special kind of moment when you hit that first note of a solo and you literally get nothing.” He’s played with David Bowie and the Cure, but Reeves Gabrels says things don’t always go right, even for the pros