Five Essential Peter Green Live Solos

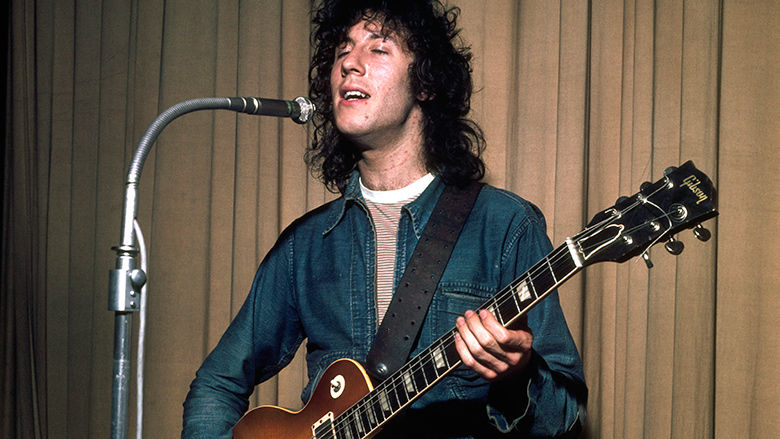

Hear some of the late, perennially underrated blues-rock pioneer's most astounding guitar moments.

Eric Clapton, due to his tenure with John Mayall's Bluesbreakers, is often credited with being the first musician to play searing blues-inspired solos with his Gibson Les Paul plugged into a Marshall running at maximum volume. Indeed, Clapton's solos would in turn inspire thousands of guitarists the world over.

However, in retrospect, a revelation has occurred with the emergence of many historic live-bootleg recordings that have been shared on YouTube since 2007. That revelation is the late British guitarist and singer-songwriter Peter Green - co-founder of Fleetwood Mac and Clapton's replacement in the Bluesbreakers.

5. "All Over Again/Got a Mind to Give Up Living"

4. "Jumping at Shadows"

3. "Green Manalishi"

2. "So Many Roads"

1. "If You Let Me Love You"

Revealed and documented within these archival recordings are some of the most brilliant, emotive, melodic and bluesy improvised guitar solos ever played, giving proof that Green's playing rivaled the work of Clapton.

It was also during this period that blues legend B.B. King said of Green: "He has the sweetest tone I have ever heard. He was the only one who gave me the cold sweats."

From what exists on these live recordings, it's easy to see why King felt that way. From blistering runs to the most soulful of melancholic sustained notes, Green had it all.

Of course, over the years, many have focused on the musical union between Green and his "Holy Grail" 1959 Les Paul, with its modified neck-position humbucker that gave him enhanced dynamic control over the tones he created.

And though that guitar did indeed play a large role, if you really take the time to listen, what you'll discover is the sound of pure musical intuition - Green's heart and soul being bared, and soaring through the medium of his guitar.

Some of Green's earliest (and best) live work with John Mayall can be heard from the recording of Mayall's show at the Manor House in 1967 (released as John Mayall's Bluesbreakers Live in 1967).

His ferocious virtuosity on "So Many Roads" and "Stormy Monday" is on perfect display during that show, as Green (only 21 at the time) can be heard unleashing torrents of emotion through his '59 Les Paul.

As the concert evolves, Green becomes a paramount of fire and grace, playing as if his life depends on every note. Perhaps his fiery display was intended to break through the looming shadow of Eric Clapton - a shadow created by Clapton fans who were quite hostile at the thought of someone trying to replace their guitar god.

Green's tenure with the Bluesbreakers was certainly a critical union - especially in the wake of Clapton's departure - as it helped establish Green, and resulted in the seminal album A Hard Road (February 1967). Unfortunately, their union was to be short-lived.

By July 1967, Green left Mayall's side to form his own band, Fleetwood Mac, with bassist John McVie and drummer Mick Fleetwood. That career move had, by the end of 1968, turned into a golden one as Fleetwood Mac would become the reigning young royalty of the British blues-rock scene (even topping the charts with their classic instrumental, "Albatross").

Despite his newfound success, it wasn't long before Green began to feel frustrated again, as he began moving artistically and creatively beyond pure blues. In the years between 1968 and 1970, Green would develop musically in glorious ways. He forged ahead to create the mystical and unique songs "Black Magic Woman" and "Oh Well, Part 1" from Fleetwood Mac's 1969 album, Then Play On.

Fortunately though, Green never seemed to lose his special connection with the blues, as some his absolute best solos were improvised over B.B. King covers. "Got a Mind to Give Up Living/All Over Again" (recorded live at The Warehouse, New Orleans on January 31, 1970, while the band toured with the Grateful Dead) and "Let Me Love You" (from the Boston Tea Party in February 1970) are particular highlights of this category.

Green could also be considered a pioneering father of heavy metal with his dark and brooding composition "Green Manalishi" (also from Then Play On).

There are several live versions of "Green Manalishi" that exist, but the improvised solo he played at the Roundhouse Chalk Farm in London, England on April 24, 1970 is epic in the way it evolves. With each passing phrase, both melodically and passionately, he can be heard reaching new heights of feeling and expression on the guitar.

By 1970, Green's life changed drastically, as he began loathing the fame and money he had made with Fleetwood Mac. During that time, Green became increasingly religious, and he eventually suffered a mental breakdown (reportedly initiated from a now-infamous incident where he disappeared for three days and took a heavy dose of acid at a castle in Munich).

Sometime after that incident, he claimed to have had a vision of an angel holding a starving Biafran child in her arms, and the vision inspired him to give his life to charity work.

Outside of the U.K., Green rarely received Clapton-level acclaim for his music. Thankfully though, in the decades that followed his departure from Fleetwood Mac, the genius and prowess of Green's singing and guitar playing developed a cult following that slowly been earned him a rightful place among the world's greatest electric blues players.

My hope and suggestion for anyone who cares about the history of blues and rock is: take your time, and give a good listen to all the historic live recordings available out there. A key thing anyone is sure to discover is that Green never improvised the same solo twice. Green's music is really a thing of beauty and joy, and his legacy stands monumental, otherworldly and transcendent.

But don't take my word - just listen to the music.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“We’d heard Jimi Hendrix, we'd heard the Who, but now we finally got to see these guys. And watching Jimi Hendrix burn his guitar….” Grace Slick on Hendrix at Monterey, Jefferson Airplane and the Spanish origins of “White Rabbit”

“I’m still playing but I’m covered in blood. Billy’s looking at me like, ‘Yeah! That’s punk rock!'” Steve Stevens on his all-time worst gig with Billy Idol — and the visit to Jimi Hendrix's grave that never happened