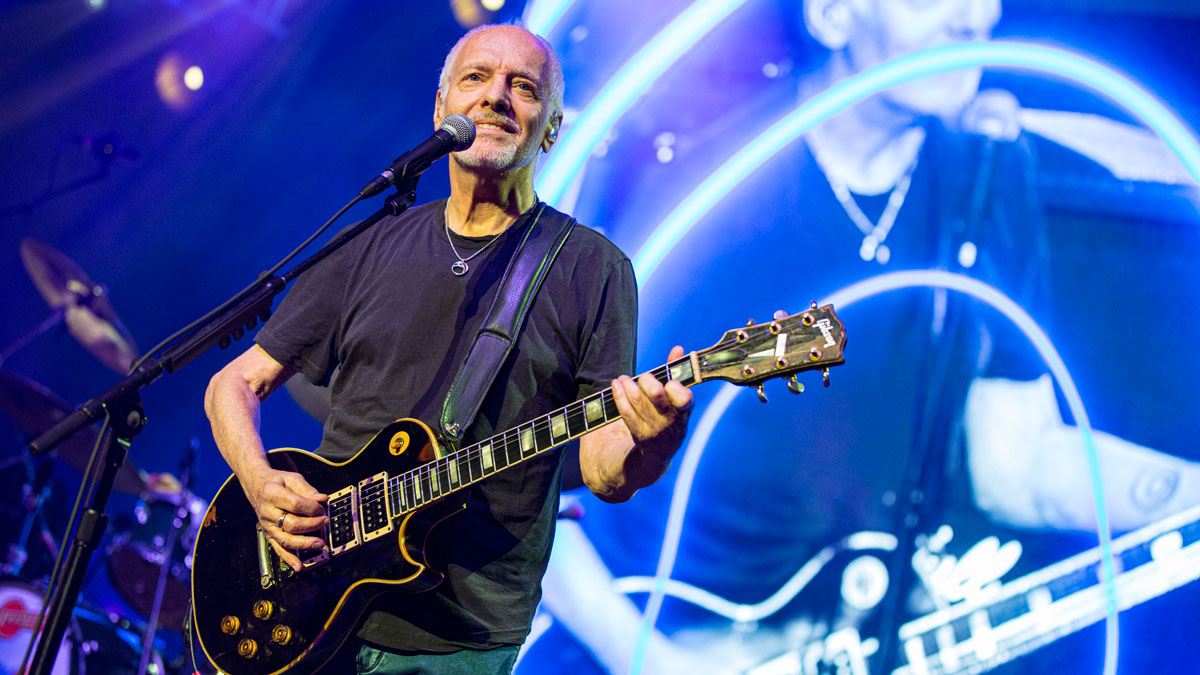

Facing the End of His Performing Career, Peter Frampton Charges Full Speed Ahead

Peter Frampton tells GP why, in the face of a rare disease, he chose to record a pair of classic blues albums.

The recent news that Peter Frampton will stop touring in 2019 has alarmed fans, and with good reason.

The legendary guitarist has revealed that he has the rare auto-immune disease Inclusion Body Myositis (or IBM). The progressive muscular disorder causes muscle inflammation, weakness and atrophy. Frampton expects IBM will ultimately hamper his ability to play guitar, and, being a perfectionist, he’s decided to launch one last tour — the Peter Frampton Finale: The Farewell Tour — before the disease makes performing difficult.

“What will happen, unfortunately, is that it affects the finger flexors,” he explained when the news broke. “So for a guitar player, it’s not very good.” Frampton says that, while he has felt the effects of the disease in his fingers, he can still play. “But in a year’s time, maybe not so good.”

Foreboding as this may sound, it doesn’t mean Frampton is going to stop making records anytime soon. In fact, just minutes before interviewing the guitarist for this story, three cuts from his upcoming blues album hit my inbox. When Frampton’s call came in, I was only part way though listening to his covers of Willie Dixon’s “I Just Want to Make Love to You,” Taj Mahal’s “She Caught the Katy” and Hoagy Carmichael’s “Georgia on My Mind,” which Frampton interprets beautifully as an instrumental.

“It’s all my favorite stuff — just standard blues songs that I felt I could really get my teeth into,” Frampton explains. “It goes from Willie Dixon– type songs to Muddy Waters and Miles Davis. We even do ‘All Blues’ from [Davis’s] Kind of Blue, which we had the great Larry Carlton come and play on. Kim Wilson from the Fabulous Thunderbirds, who is one of the best blues harp players I’ve ever heard, also joined us on three tracks, two of which are on the first volume.”

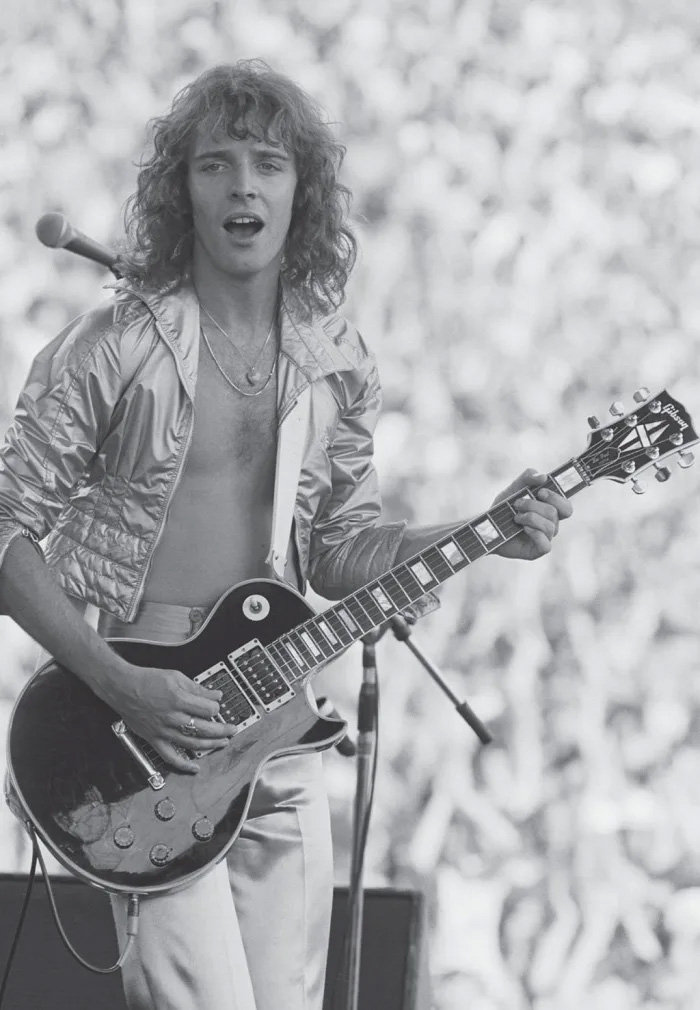

This is just the latest chapter in what has been Frampton’s long and varied career. After starting out in 1965 at age 16 with the British pop rock group the Herd, he joined Humble Pie, where he established himself as one of rock’s premier guitarists. He launched his solo career in 1972 with the band Frampton’s Camel before achieving superstar status in 1976 with his multi-Platinum breakthrough album, Frampton Comes Alive! His 2006 release, Fingerprints, was his first instrumental record, and he’s continued to issue albums at a rate of every three or four years. If Frampton’s current studio output is sustained to even a fraction of what it is now, we can likely expect to hear a lot more music coming from him in years to come.

So you have actually recorded two albums worth of blues tunes?

Yes, in the first 15 days we cut, like, 33 tracks. We did the first batch in 10 days, took some time off and came back and did another five days, and that was enough for two albums. In fact, more than that. The first volume is called All Blues, and it’s the Peter Frampton Band — I’m giving us a name for the blues stuff. There will be another blues album coming, as well an album of instrumental covers. Since we had some time left over, we started my next solo record too. We’ve got three tracks down, so we’re looking a couple of years ahead.

Were any other players enlisted for the blues project?

Yes, Sonny Landreth. Sonny had played with us on the Guitar Circus tour, and B.B. King was on it for about a month, opening up for us as a special guest unbelievably. I had to pinch myself on that one! Each night I’d get the call to go and jam with B.B., so I’d go out there and sit with him, and we’d talk and jam on “The Thrill is Gone.” When I thought about recording it for my blues album, I was thinking, I’m not sure I can do that one, it’s such a B.B. King song. We were just messing around with it, and then we got Sonny to come and overdub a solo with me. Even he said, “I was worried, because you’re touching something that is such a B.B. classic.” But we just felt that if there was ever a way to pay tribute to him, it was to do a good version. [laughs] I leave it to those who listen to make their own minds up, but I think it’s a phenomenal version.

Where did you record these songs?

I have a full-fledged studio in Nashville that I was able to pick up when I moved here. Since October, we’ve done over 40 tracks there. I’ve been recording as much as I can in the shortest space of time because I don’t know how long I’m going to be able to play. I haven’t recorded this much in such a short space of time in my entire career.

What guitars did you use on the new record?

For the majority of this record I’ve been playing a ’59 ES-335. But I did also use my ’54 Les Paul — we call it the Phenix now — that I got back in 2012. [The famed three-pickup Les Paul, which Frampton used with Humble Pie and during his early solo career, vanished for more than three decades after the cargo plane transporting it crashed in Venezuela in 1980.] So it was mainly those two guitars, along with a Strat that I used on one song.

What amps did you use?

I had a Vox AC15 from 1964 and my ’65 Fender Deluxe Reverb, which is an animal. If you were to get three 1965 Deluxe Reverbs and put them next to one another and plugged into each, they’d all sound different, and this one is just a brute. It’s a got a real fiery tone.

So, you don’t use any amp plug-ins in the studio?

Given the choice I would always use a real amp. Plug-ins are wonderful, and they are getting better and better, but there’s nothing like plugging straight into an amp. All the best sounds I’ve ever got were just the right guitar plugged into the right amp at the right level. It’s the same for playing live, too, because I have to be close to my amp. Having nothing onstage and relying on monitors kind of defeats the purpose for me. I use the in-ear monitors but I’ve got my amp right behind me so I’m feeling it as well as hearing it. I use the same system I’ve used for years now. It’s lots of bells and whistles, but it means that I can play every sound that I need from all the records.

You get a very rich overdriven sound on the new tracks I’ve heard. Is there a particular pedal that gets some credit for that?

You know, I’ve recently been using the Origin Effects Revival Drive. You can plug into a Fender and make it sound like a Marshall, or vice-versa. I don’t know if you need to do that, but I find that most distortion units either work well with a Marshall-type amp or they work well with a Fender-type amp. They usually don’t with both, but this one does. It works well with everything. I haven’t used it live yet, but I think I’m going to. I got it right after the last tour, and now we’ll be gearing up for the new tour and I’ll be taking things out of the rack and putting other stuff in.

Are there any other new effects that have found a place in your system?

I’ve known Eventide’s Rich Factor [an inventor and one of the company founders] for longer than I care to remember, and I think I got the first harmonizer they ever made. Of course, they’ve got the H9 [harmonizer/multi-effects pedal], which is wonderful, and I have one of them on a little B-rig board that I use with a single amp. But they've also come up with this pedal called the Rose Delay, which I believe they premiered at NAMM last January. It’s a rich-sounding and phenomenal delay unit that has a different way of modulating the sound with the speed and depth controls. It’s so close to having a reel-to-reel tape deck next to you, with a variable speed, and the way you can get it to wow and flutter is incredible. It was basically a one-trick pony when he first sent me one, but then I said it would be great if we could have some presets. So now you’ve got five customizable presets, and they went a step further by making it MIDI, so you can have a million presets if you control it with a MIDI device, which I will probably do.

What are your favorite acoustic guitars?

When I left Humble Pie I bought a D-45 Martin from Manny’s in New York. I recorded all of [1973’s] Frampton’s Camel with that, so “Lines on my Face” and all those acoustic things are with that guitar. Then we went out on the road and it got stolen, and I never really could bring myself to buy another Martin, because I missed that one so much. But I still had my Epiphone acoustic that I had bought when I was in Humble Pie. It’s the same year and model as Paul McCartney’s, except his is blond and mine is sunburst.

So anyway, in the early 2000s, I went to the NAMM show and saw Dick Boak from Martin there, and I told him the story of losing my D-45. He said, “You mean you don’t have a Martin? We’ll have to make you one.” So, he asked what I would like, and I told him that I didn’t need all the inlay, so let’s make it a D-42. I said that I loved the Stephen Stills high-end twinkly sound, so he suggested an Adirondack top. Since my D-45 only lasted through the Frampton’s Camel album, he thought to call it the Frampton’s Camel D-42 and put a little design of a camel on the headstock. So I’ve got a bunch of those guitars. Epiphone also just released a signature model [the Limited Edition Peter Frampton “Texan”] that’s just like mine, except it sounds better. It’s a workhorse with a beautiful sound, and I use it live too.

Did Epiphone actually take your guitars to spec out for the reissue?

Yes, they did with the acoustic. With the “Phenix,” however, Gibson scanned it as soon as I got it back, so I believe they passed those scans onto Epiphone for that one. I have to say they did a phenomenal job because it plays and sounds great.

What gauge strings do you have on your acoustics and electrics?

I use D’Addario or Elixir strings on the acoustics, and I regularly use an .011 through .052 set. On my electrics I use a .009 through .042 set, or .009 through .044 if I’m tuning a half-step down. Again, because of the slight weakness in my hands I might have to go down a gauge. We’ll see.

You always get a great slide sound. What slides and tunings do you use?

I use the shorter glass slide and sometimes a thin metal one. My go-to tunings would be open G or A, but a slide tuning really depends on the key of the song, and what kind of sound and notes are needed. Open E or D has a completely different effect aurally from open G or A. I even tuned to a C chord for the slide on the studio version of “Somethin’s Happening.” I love open tunings for writing, because a new tuning is like playing a different instrument with new inspirations.

I think one of your standout acoustic pieces is “Ida Y Vuelta” from the Fingerprints album. What did you play on that song?

I used on old Tacoma Chief on that one. I have two of them actually, and they have a unique sound. I’m playing it with my fingers on that track, for the rhythm part anyway, and it’s got this biting sound that I love.

Also, on Fingerprints, there’s a song called “Souvenirs de Nos Pères” [“Memories of Our Fathers”] where you nail the Django sound. Can you talk about that tune?

I had wanted to do a Django tribute, and John Jorgenson and I had both lost our fathers recently, so that was basically a tribute to them. John came up with that whole melody and played it to me, and I said, “Oh my god, that’s fantastic!” Then I had to shed for about a month to be able to play it.

Did you use a Macaferri-style guitar for that track?

It was a Gitane, the one with the oval soundhole. I have one now that was built by Dupont in France, and I firmly believe that if Django were alive today he would be playing a Dupont, because it’s so good. When I got it out of the case and picked it up and played one chord on it, I got chills. It’s that sound! It’s inspiring to play even if you’re not playing Django style. On that guitar, I use the Argentine .010 strings, which is what Django apparently used. It’s easier for me with that gauge.

You still tour with valuable vintage guitars. How do you deal with well-founded concerns about that?

Well, when I got the Phenix back, everyone said, “You’re not going to put that on the road are you?” And I said, “Not take it on the road? It’s lived through an air crash, so I think it will be okay.” That’s all I used to play for 10 years after I first got it, so obviously I’m going to take it out with me. I also take a 1960 Les Paul that was owned by JJ Cale. He sold it to his producer Audie Ashworth, and when he passed away, his wife wanted it to go to a good home and I was the lucky recipient of this beautiful ’burst. We lost so much stuff in the 2010 Nashville flood, and I was very fortunate that it was insured. But instead of replacing everything, which is multiples of guitars that I didn’t play anymore, I just went out and got a good one of each. I have a great ’63 Jazzmaster and a ’58 Jaguar, and I recently I got a really nice ’59 Tele. I just got some choice pieces as opposed to replacing everything.

Blues was huge in England when you were coming up. How did you manage to evolve your playing into something noticeably different from what, say, Peter Green, Mick Taylor and Eric Clapton were doing?

When I started to go see John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers with Eric Clapton up in London and other places, I suddenly realized that everybody was trying to be Eric. They were trying to look like him, play like him and use the same stuff he used. I loved Eric’s playing, always have. He’s been a major influence on everyone, including me, because his licks are masterful and it’s such a beautiful clean blues style. But I felt that everyone was going to end up sounding like Eric Clapton. It’s just too seductive, and I’ll go there too. However, because of my parents having brought me up on Django Reinhardt and Stéphane Grappelli, I had this sort of inbred jazzy side to me from a very early age. When I was about 13 or 14, I started listening to Wes Montgomery, Kenny Burrell and Joe Pass, and then, later on, a very young George Benson with the Jack McDuff trio. So before and during the Herd was when I was really burying myself in those guys.

Would you say your jazz-informed blues-rock style fully came to fruition in Humble Pie?

Yes. When Steve Marriott and I formed Humble Pie and we were jamming together, he was hard blues and I was more lyrical jazz rock. I’m putting myself in my own box there, but that’s the only way I can describe it. The combination of the two styles pushed me into the first couple of albums of Humble Pie where I found that I had a style of my own. It wasn’t blues and it wasn’t jazz, but it was everything I’d got in my library of licks in my head, and now it’s just coming out sounding like me.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Art Thompson is Senior Editor of Guitar Player magazine. He has authored stories with numerous guitar greats including B.B. King, Prince and Scotty Moore and interviewed gear innovators such as Paul Reed Smith, Randall Smith and Gary Kramer. He also wrote the first book on vintage effects pedals, Stompbox. Art's busy performance schedule with three stylistically diverse groups provides ample opportunity to test-drive new guitars, amps and effects, many of which are featured in the pages of GP.

"This 'Bohemian Rhapsody' will be hard to beat in the years to come! I'm awestruck.” Brian May makes a surprise appearance at Coachella to perform Queen's hit with Benson Boone

“We’re Liverpool boys, and they say Liverpool is the capital of Ireland.” Paul McCartney explains how the Beatles introduced harmonized guitar leads to rock and roll with one remarkable song