Ethan Gruska Decodes His Songwriting and Explains Why It's All About the Vibe

Gruska’s “naïve” approach to guitar creates beautiful moments of surprise on his sophomore solo album, 'En Garde.'

Ethan Gruska's approach to recording isn’t to get a perfect take, or even one with swagger or feeling. Sometimes the mistakes are what make the song.

For En Garde (Warner Records), his second solo album, Gruska - whose writing credits include John Legend, Kimbra and others, and production credits include Manchester Orchestra and Phoebe Bridgers - invited friends and collaborators like Blake Mills and Phoebe to perform.

But instead of using their contributions in a straightforward manner, he used the interesting, unscripted moments to turn the songs on their heads. The technique is well suited to Gruska’s compositional style.

Drawing inspiration from the same well as eccentrics Brian Wilson and Elliott Smith, and imbued with the melodic sense of Jeff Buckley, his compositions veer away from conventional chord progressions and song structures.

“I like being surprised and a little bit confused, and I think that growing up, it just sort of absorbed into my style of writing,” Gruska says. “I lean toward harmony rather than melody, so if I’m writing a weird batch of changes, and have to sing a melody through it, it can get sort of squirrely. Maybe that’s why some of the melodic steps seem sort of like a surprise - because they end up being rather unconventional.”

Gruska’s adventurous, cinematic vision for his music comes naturally. His grandfather is composer John Williams, who has written now-iconic movie scores for the Star Wars film franchise, Jaws and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, and dozens more.

There’s something about writing on guitar that is a little bit more naïve for me

Gruska says of his famous grandfather, “As I’ve gotten older and maybe become more understanding of what he does and how he does it, he’s been really lovely and has given me very short and poignant notes about what to listen for, what to look for.

"I think the most valuable thing he ever said to me was to not be one-sided in my creativity. If you’re going to be a musician, read. Or if you’re going to be a composer, walk around in nature and gather inspiration, not just from other music. There’s so much more to learn.”

Your use of guitars is very textural. What’s your background with the instrument?

I’m self-taught on guitar. I’d say piano is my main instrument, only because I sort of know what I’m doing on it. But that’s why I love guitar, because when I’m writing on it there’s a little bit of a mystery to what’s happening. I’m following my ear more than my brain.

I ended up playing guitar in a few touring bands, one of which was [folk-soul artist] Ray LaMontagne. That was amazing for me, because it was learning by fire, and I had to learn how to really play lead guitar and rhythm guitar in front of an audience. After that, I started to feel more confident to play guitar on other people’s records and onstage.

My hands are working, but because I don’t necessarily know what I’m playing, I end up creating some unusual chords and changes

Is not having to think about music mathematically part of the attraction?

Totally. It’s all vibe, which is so important. It actually influences my piano playing, too, when I want to write something on guitar and transfer it to piano. I’m seeing the piano in a new way. With guitar, it’s like a series of accidents. There’s something about writing on guitar that is a little bit more naïve for me. It usually comes out a little less overcomplicated.

When I play piano, I sometimes want to push myself to be more harmonically dense. I don’t have that ability on guitar, so there’s a bit more of purity to what I play. I think the guitar songs just have a different heart to them. They’re a little more wide open and come from a more innocent place.

What’s a good example of that discovery on En Garde?

I think a good one is a song called “Maybe I’ll Go Nowhere.” It’s in an open tuning, which is yet another iteration of me sort of trying to trick myself into doing something different. It’s all just geometric for me. My hands are working, but because I don’t necessarily know what I’m playing, I end up creating some unusual chords and changes. The resulting music has a very distinct mood.

“Attacker” is another song from the album that I’m really proud of, because harmonically it’s denser than what I usually play on guitar. I just happened upon a kind of move that was really fun to write over.

Do you map out the songs ahead of time, or do you catch inspiration on the fly?

I usually write the song as a bare-bones thing before I start doing anything textural. Then, when I start recording, I’m just immediately going for that textural stuff. I’m using a lot of sampling and field recordings and a lot of reversing things.

So usually I’ll write something, put that down and then try to have a lot of nice accidents happen with sampling that leads me toward an arrangement. I like having that come immediately after the writing process. It leads you down a more interesting road.

Is that where your sound collages come into play?

Definitely, especially on this record. I knew that had to be the centerpiece of the production, that sort of degraded sonic collage, with subtle and nuanced things. A lot of it is guitars with pedals and all these crazy instruments.

I did it at Sound City. The two people that are running it right now, Tony Berg [with whom Gruska co-produced Phoebe Bridgers’ Stranger in the Alps] and [Alabama Shakes producer] Blake Mills have an insane collection of gear. Lots of instruments from all around the world.

What were your go-to instruments?

There’s a guy in Los Angeles named Reuben Cox who runs a shop called Old Style Guitars. He started making these guitars that have a rubber bridge. He takes off the bridge, puts on this piece of rubber, and, basically, it kills all the sustain and almost makes it sound like a pizzicato viola or something. It just has this really plucky, woody sound.

I just got obsessed with that sound, and I’d say that I used it for 90 percent of the acoustic and electric guitar parts on this album. If I was basing a song around a guitar part, I would always gravitate to that. Not only does it kill the sustain but it takes off high end and makes things sound dusty immediately.

It really does leave a big sonic signature on the record. I thought you were doing that in post with noise reduction or compression so it sounded choppy and clipped.

I love it so much, because that’s what I gravitate to when I’m filtering a sound. I love pillowy, warm things. I’m always reducing high end and adding degradation, and this rubber bridge immediately creates that sound.

- Ethan Gruska's En Garde is out now via Warner Records.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Jim Beaugez has written about music for Rolling Stone, Smithsonian, Guitar World, Guitar Player and many other publications. He created My Life in Five Riffs, a multimedia documentary series for Guitar Player that traces contemporary artists back to their sources of inspiration, and previously spent a decade in the musical instruments industry.

"Shredding is like talking a foreign language at 10 times the speed of sound. You can't remember anything." Don Felder reveals the unlikely influence behind his iconic guitar solo for the Eagles' “One of These Nights”

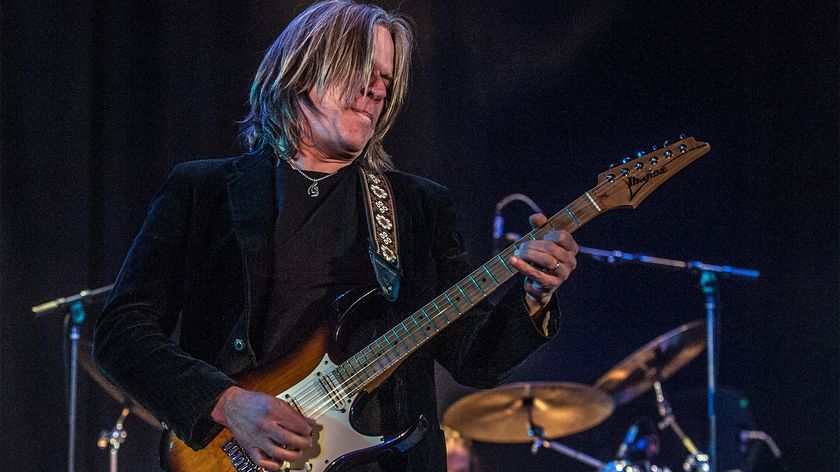

"Old-school guitar players can play beautiful solos. But sometimes they’re not so innovative with the actual sound.” Steven Wilson redefines the modern guitar solo on 'The Overview' by putting tone first