“He said, ‘Come by the studio tomorrow and bring your guitar.’ All at once, my life changed.” How an unknown guitarist turned a lunch date into session work on the biggest hits of the 1980s

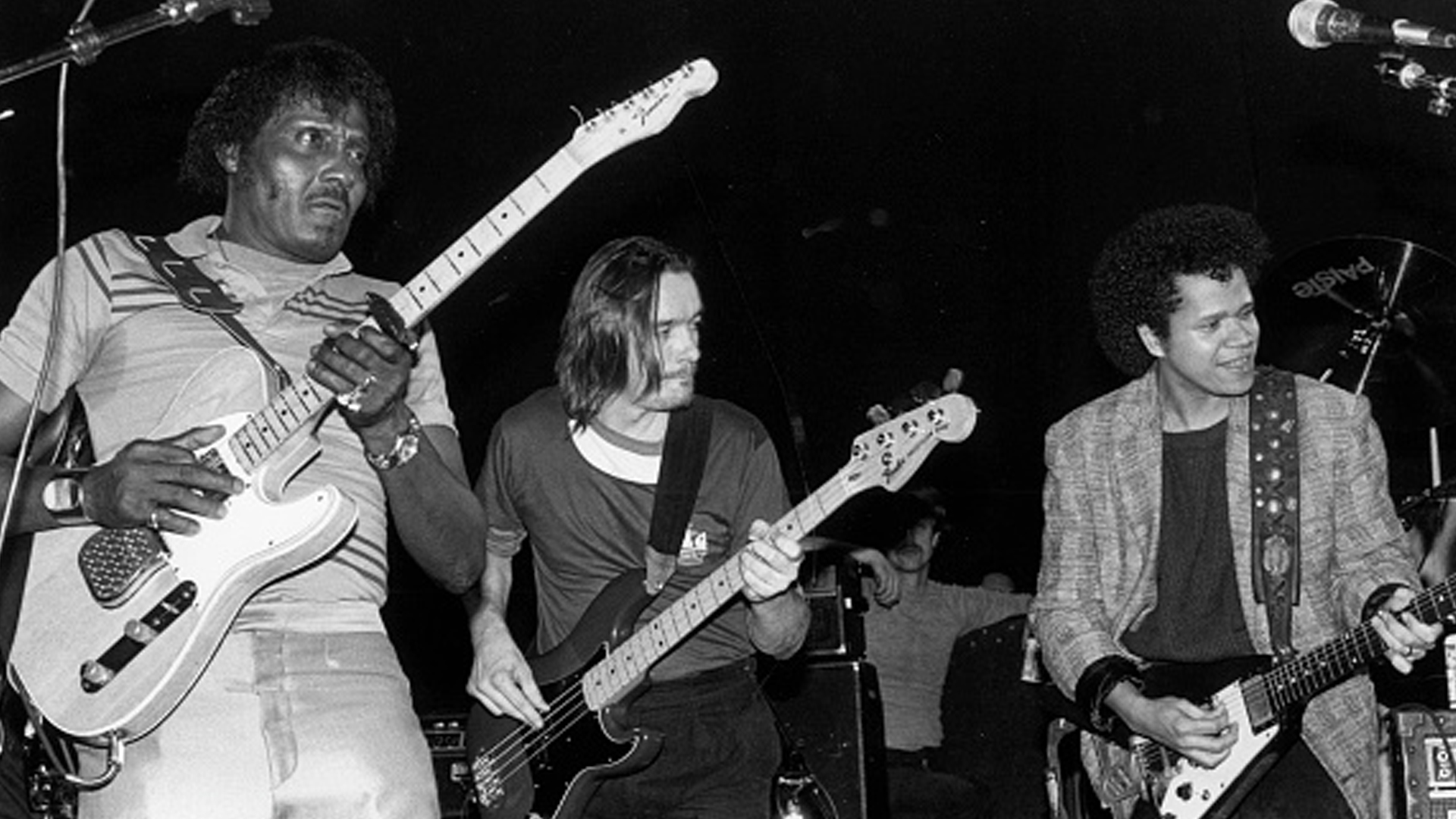

Eddie Martinez had scored a few hot touring gigs during the late ‘70s — playing with LaBelle and then with Stanley Clarke and George Duke — but by the early ‘80s he set his sights on cracking the New York City session scene. “I probably couldn’t have picked a worse time,” he says. “All the hot players were in Manhattan, and everybody was out for the same jobs. I had a hell of a time getting noticed. Knocked on a lot of doors.”

It was at a particularly low point in 1982 when Martinez looked up an old friend: bassist and producer Bernard Edwards, famous for his groundbreaking work with the band Chic. The two met for lunch, and Martinez pitched himself as a guitarist for the solo album Edwards was cutting. “All at once, my life changed when Bernard said, ‘Come by the studio tomorrow and bring your guitar,’” Martinez recalls. “That was the real door opener for me. I can remember it so vividly.” He laughs. “I can even remember what Bernard was eating: fried flounder with chili sauce.”

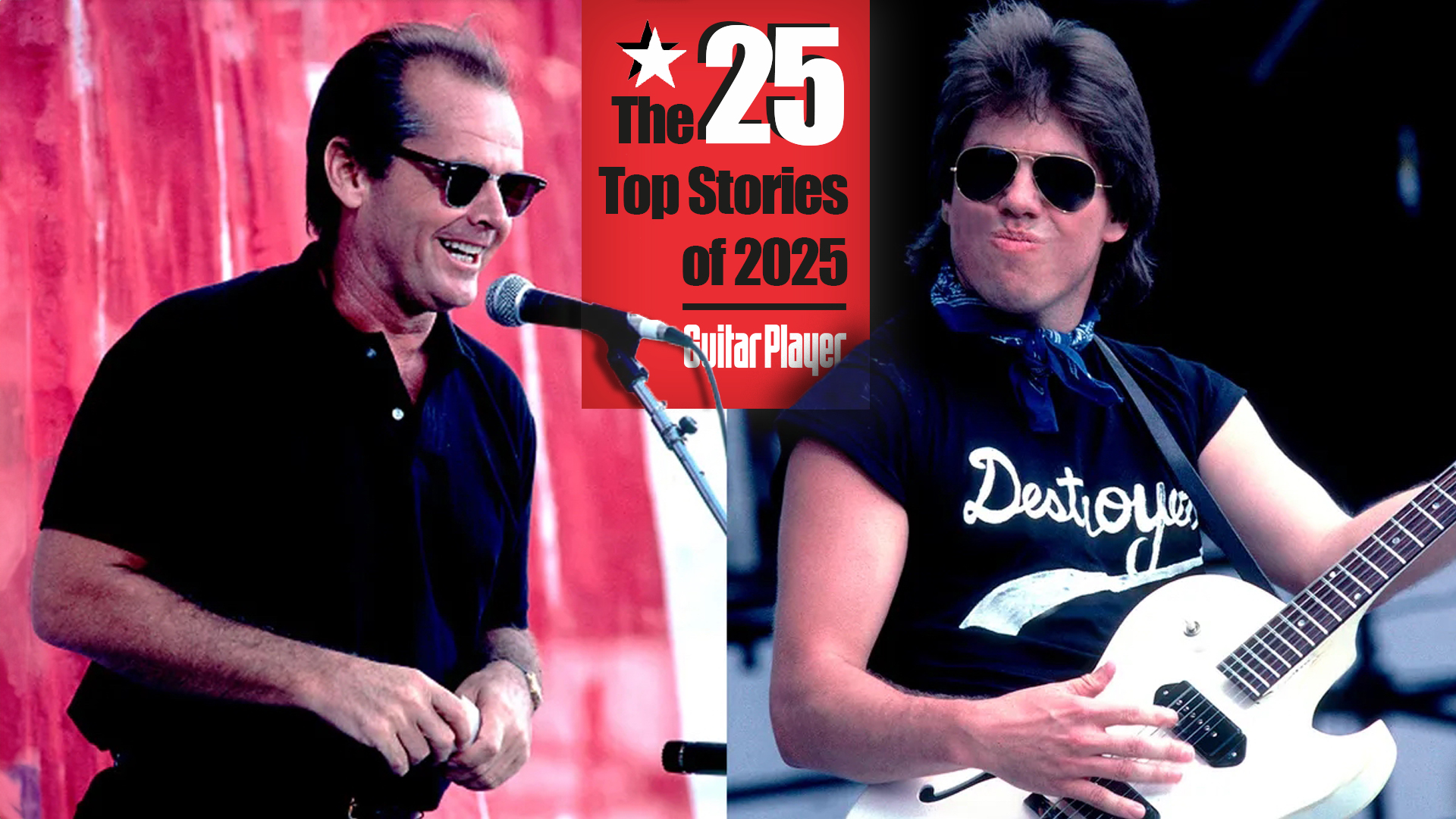

Before long, Martinez, heretofore New York City’s best-kept guitar secret, would become the secret sauce on hit recordings by Run-DMC, Robert Palmer, Steve Winwood, Billy Ocean, Mick Jagger, David Lee Roth and a fleet of other music greats. During much of the ‘80s, his diverse playing — everything from earth-moving rhythms to silky grooves to face-melting leads — seemed omnipresent on both MTV and radio. “I waited so long for my day in the sun, so it felt like validation when things finally happened,” he says. “I had seen a lot of my buddies get the big gigs. After a while, you start to feel like you’re standing around at the prom waiting to be asked to dance. That’s what was so frustrating: I knew I could play. I just needed the shot.”

For many of those sessions, Martinez made his electric guitar of choice a red Hamer prototype. "I used that same guitar on all the Run-DMC and David Lee Roth stuff," he told Guitar Player in its February 2004 issue. "It had a triple-coil pickup, so I could get humbucker or single-coil sounds out of it. I plugged it into a non-master-volume Marshall from the late '70s, and a 4x12 cabinet loaded with 25-watt Celestion Greenbacks. I ran the volume at around eight or nine, because if you cranked that amp you'd lose a little definition, I didn't max out the bass — I let file mids handle the low end of the sound--and I ran the treble at just over halfway."

Now living in Portland, Oregon, Martinez hasn’t exactly retired, but he doesn’t work on the clock anymore. “I play around town and throughout the country, and I’m finishing up an EP with my band,” he says. “I’m content with what I’ve accomplished.

“I don’t look back too often, but occasionally I’ll sit back and reminisce. I feel very blessed to have worked with a lot of special people, some of whom aren’t here anymore, sadly. That’s the really beautiful thing about music — the friendships you forge.”

“ROCK BOX” — RUN-DMC

“I had played in bands with Larry Smith. He was a bassist who became a well-known producer of hip-hop and rap. One day he called and said, ‘Eddie, I want you to put some rock shit on this thing I'm doing for Run-DMC.’ I had vaguely heard of them, so I said sure and went down to Green Street Studios.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“I hadn’t heard the track before I got there. Larry had laid down a bassline over a DMX drum machine beat, and there was a little twinkling keyboard line. That was all they had. Larry knew my playing well, so I think he felt that whatever I was going to come up with would work. I just kind of went for it. I laid down a big fat rhythm as a foundation, and then I started to build an orchestra of harmony guitars. I did a lot of tracks, just layering and layering. There wasn’t any kind of structure to the song yet — there were no vocals — so it was kind of abstract. When I played the leads, I thought about Brian May’s guitar sound and how the tracks were stacked. The end result was this cool tape saturation that really came alive.

“People think I had this wall of Marshalls on that cut, but in reality it was an amp they had at the studio — a Music Man with two 12-inch speakers. My guitar was the red Hamer prototype that I would play on a lot of hits, and the only pedal I used was a Boss overdrive. That was it. The whole thing was rather serendipitous. The second I started playing, I had my sound.

“I had no idea what we were doing would be groundbreaking, and to be honest, when the Run-DMC guys heard what I did, they were a little taken aback. They thought the guitar would overpower their words. In the end, it opened up a new world for them, and they came around. Once the record sales started happening and the coins came in, everybody was happy.”

“ADDICTED TO LOVE” — ROBERT PALMER

“Robert Palmer had asked me to play on the Riptide album when he was doing the Power Station record. I went down to the Bahamas to work with him and Bernard Edwards. Robert played me a rough demo of ‘Addicted to Love,’ and I thought it was great, but it wasn’t a situation where the demo was so perfect that you had to beat what was on it. There was some guide guitar work on it, but Robert wasn’t beholden to anything. It was a collaborative project in the best sense of the word.

“We cut the track live, and I started to play what I felt. Robert and Bernard knew my playing, so they let me explore the song. Most of what I did is emblematic of my sound — big crunchy parts, bordering on an orchestral feel, but I also played these clean, classy parts during certain parts. You might hear that kind of thing in funk or pop, not rock. I liked the two extremes. It gave your ears a lot of nice contrasts.

“For the crunch stuff, I used my Hamer, a 50-watt Marshall and a Pro Co RAT distortion. On the classy B sections, I played a Strat into a Twin Reverb, and I added a little Boss chorus. I think we mixed in a little DI stuff, too. Later on, Andy Taylor from Duran Duran added some rhythm stuff in New York.

“The solo was something I ad-libbed on the spot. We were pretty much finished for the night, but Jason Corsaro, the engineer, and I stayed behind and worked on tones. I played the solo one time, and that was it. Instead of doing something fast and shreddy, I played slow and soulful, so each note really sticks out. It became a song within a song. I have to credit Jason for the sound — he pulled a lot of tricks to get it just right. When Robert heard what we’d done, he was floored. He really loved it. It was such a nice feeling when I could surprise him with something like that.”

“1/2 A LOAF” — MICK JAGGER

“I went to a guitar store in New York City, and a friend of mine said, ‘Hey, Eddie, I hear you’re playing on the Jagger album.’ ‘News to me,’ I said — I hadn’t heard anything about it. Then I went to a rehearsal, and I got a call from Bill Laswell, who wanted me in the Bahamas the next day to play on Jagger’s record. Apparently, I was the last to know.

“I worked on some tracks down there with a bunch of rhythm sections — there was a lot of stuff we cut that never came out. We came back to New York and did ‘1/2 a Loaf’ in New York at the Power Station. Nile Rodgers was producing this one. Generally, what would happen was, Mick would pick up a guitar and play us a song. Then we’d go about cutting it live. Nile and I played together in the same room. He’d do clean parts, and I’d play crunchy stuff. It was just natural the way we gravitated toward that arrangement. My parts are probably dominant, but Nile’s rhythm playing was very important. He laid down the foundation.

“The solo I played came to me instinctively, but there’s a motif to it. It’s big and crunchy, and it works with the song. It’s more like guitar parts than an unbridled solo. I had my red Hamer prototype with me, but I also had a similar model in gunmetal gray — I might have used that one. My amp was the 50-watt Marshall that I relied on for so many sessions. Jagger was there through the recordings. He was vibing and getting into it. You knew if Mick was dancing in the studio that shit was going right.”

“HIGHER LOVE” — STEVE WINWOOD

“Sometimes it’s hard to predict what will be a hit. Most of the time, I have no idea. But with ‘Higher Love,’ the minute I heard the track with Steve Winwood’s reference vocals, which were killer, I thought, Holy shit, this is going to be huge. And it was — it was a big seller, and it won Grammys for Record of the Year and Best Male Pop Vocal.

“Russ Titelman was producing. They had already cut a lot of the basics at the Power Station. Russ loved tight, clean rhythm stuff, so I knew going in that I would be pursuing that direction. He and Steve were very open to letting me explore what I heard, but I had to be very economical with my parts. There’s a little bit in the B section where I play some cool bits, and in the bridge I play some nice lines.

“This was a case of the small things doing a lot of heavy lifting. You might not hear everything in your face, but if you took the stuff away you’d notice that something was missing. I’m very proud of my playing here. I wasn’t trying to dominate the sound; I supported and serviced the song, and that’s what it’s all about.

“I didn’t use my Hamer on this track; instead, I played a guitar that was fashioned from a Schecter neck, a DiMarzio body and EMG pickups. It worked out great on the Winwood stuff as I was going direct. My other guitars — the Hamers and my Strats — they were cool most of the time, but sometimes I’d get buzz from them. As much as I loved those guitars, I had to be realistic.”

“SIMPLY IRRESISTIBLE” — ROBERT PALMER

"This was a different process than what I’d done with Robert previously. We cut this track in Milan, Italy — Robert had moved to Switzerland for a variety of personal and professional reasons. When I got to Italy, a lot of tracks had already been cut, so we weren’t playing live. Robert was producing, and he’d had bass guitar, drums and keyboard parts laid down. But I’ll tell you, I had a blast. I had a big rig with me — I don’t know how many cabinets, it was just mondo — and I just went wild.

“I cut crunchy rhythm guitars first — there’s no clean guitars at all. I even put a 12-string Hamer on there to fatten up what was already fat. It was just beautiful excess. My solo is nuts. It opens up with these intervals, and in the middle there’s a quasi-bop blues lick, and then there’s a sonic effect with a whammy bar sliding all these double stops, and then it ends with a whole tone scale and some kind of arbitrary, manic riff. It’s almost like three sections in one solo. Robert loved it. He called it ‘Large Marge’ from those Pee Wee Herman movies. That’s what the song needed. It’s a very aggressive song, so it felt right to just go outside the box.

“In addition to that 12-string, my guitar was a Jackson Dinky Soloist. Grover Jackson had given it to me. It was one of three he made. I know Jeff Beck had one, and a friend of mine, John McCurry, had the other one. They were great guitars, and they really did the job.”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.