"Conan O’Brien asked me: 'What do you consider your greatest contribution to music?' I said, 'Not singing.' I never had a good voice for singing, so I took it out on the guitar." An epic Duane Eddy interview by Bill Nelson

Back in 2012, we brought electric guitar pioneer Duane Eddy and visionary British legend Bill Nelson together for an epic interview. Topics covered include everything from meeting Elvis, swapping tips with Chuck Berry, pioneering a whole new playing style, and the idea of making a dark, ambient album…

When Duane Eddy died on 30 April, one of the many guitar players to mourn his passing was Bill Nelson. "I owe Duane so much," he wrote on Facebook. "I was just ten years old when I first heard the sound of his guitar. That was in 1958. Duane’s single, Because They’re Young, was the first record I ever owned.

"I made a cardboard copy of Duane’s Gretsch 6120 guitar and would mime to the single in front of my bedroom mirror, pretending I could play. It was the start of a lifelong relationship with music and the guitar, a relationship which continues today, and I thank Duane for inspiring me and setting the spark.

"Later on I interviewed Duane for Guitar Player magazine. We continued exchanging emails and I looked forward to his Christmas greetings each year. He would comment generously and positively about my own music, always encouraging and kind. A lovely man and an iconic musician. I will miss him so much and cherish my memories of him…"

The interview he refers to took place in 2012. Bill’s insights and enthusiasm and Mr. Eddy’s open and honest responses exploded into a 12,000-word opus, and we reprint it here as a truly wonderful and informative interaction between two incredible guitarists who had the utmost respect for each other.

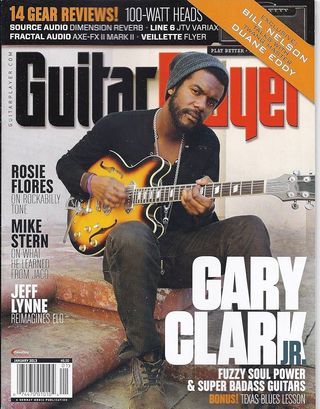

This is the complete, unedited transcript – an abbreviated version appeared in the January 2013 issue of Guitar Player.

Bill Nelson: First of all, I’d like to take you back to your childhood. In later years you were strongly associated with Arizona—and because of the recordings, Phoenix in particular—but you were actually born in New York State.

Duane Eddy: I was born and spent the first several years of my life in upstate New York, a couple of hundred miles west of New York City.

What music did you hear there?

From the age of 5 or 6, I listened to the radio at night. On the weekends, I tuned into WLS Chicago, WCKY Cincinnati, Ohio, and WWVA Wheeling, West Virginia for their Barn Dance program on Saturday nights. I also picked up WSM’s The Grand Ol’ Opry on Saturday nights when possible. It was all country music, and I loved it. Every Saturday afternoon during the summers from age 7 until I was 10, I went to the movies to see cowboys like Gene Autry, Roy Rogers, Rex Allen, and others. I loved the western music they played in those films!

I read lots of American cowboy comics when I was a kid. It was a popular thing with boys in England in the 1950s. I actually joined the Roy Rogers Club, and the Hopalong Cassidy Club, too! So, how did the guitar enter your life? I read somewhere that you first took up the guitar at the age of five—a remarkably young age! How did that come about?

I first discovered a guitar when I was almost six years old. One afternoon, I saw a small acoustic guitar standing in a dark corner of the cellar. I asked my father what it was, and he told me, explaining that he used to serenade my mother with it when they were courting. He showed me five or six chords—which was the extent of his knowledge—and I just kept after it and fell in love with it. I was eight or nine years old before I saw anyone play up and down the neck and realized there was more to it than those chords at the end of the neck down by the nut. What a wondrous revelation that was for me!

That resonates with my early experiences with the guitar. My father was a saxophonist, but in his younger years had played banjo and guitar. My first guitar was a little plastic toy with just four strings. My dad showed me how to play four ukelele chords on it, and that was the only guitar lesson I ever had. Was your family supportive of your developing talent?

Always. They encouraged me to perform at school talent shows, and in the fifth grade in Bath, New York, I played lap-steel along with a girl who played a violin. We performed a duet of a Stephen Foster song. When I was 8 years old, my Mom took me down the road to a neighbor who had a recording lathe and was able to record a 78 rpm record. You only had one go at it, but I played and my sister sang, and we recorded a couple of Christmas songs.

That seems so wonderfully romantic! How did things develop from there?

By the time I was ten years old, we were living in a little country store/gas station in the small farm community of Guyanoga—a couple of miles north of the west branch of Keuka Lake. While there, I played and sang a couple of songs at an assembly at Penn Yan Academy where I attended school for the seventh and eighth grades. I also took three lessons on the lap-steel, and then went to play on a radio show in Hornell, New York. I played my first instrumental on radio there—a song called “The Missouri Waltz.” Somehow, my parents managed to record that part of the show, and I still have the vinyl disc of it somewhere. I didn’t continue the lessons on lap-steel, because I wanted to learn guitar. But guitar lessons weren’t available to me at the time.

It would be marvelous to hear that disc. What age were you when you moved to Arizona?

We stayed in Guyanoga until I was 13, when we packed up and went west to Tucson, Arizona. That’s where I began my teenage life.

What music were you exposed to at that particular time?

After we moved to Tucson, I began listening to radio every day after school, and playing along with country records. I taught myself to play that way. My heroes at that time were country artists such as Hank Williams, Lefty Frizzell, Carl Smith, and Ernest Tubb and his guitar player, Billy Byrd. I also loved Louis Armstrong, and later, I discovered Tennessee Ernie Ford. At age 14, I began hearing Les Paul, and then Chet Atkins, and Les and Chet became heroes of mine, as well.

Chet Atkins had a huge impact on me, too. He and Les Paul set the benchmark so high. Did you ever think in those early days that you might be able to sustain a career as a guitar player?

I had no idea of sustaining a career with music before I was 18 years old. As a ten year old, I dreamed of having a band someday, but with no concept or plan of making a career out of music. In those times—and in my little world—no one gave thought to that kind of idea.

Same here. I had pictures of you and Hank Marvin of the Shadows pinned to my bedroom wall. There were also several guitar instrumental records that I’d play on my family’s radiogram. But music seemed like a magical, out-of-reach world—a world that a working-class kid from Yorkshire could never enter. Did you ever consider formal lessons at all?

When I was about 11, I took a class in music appreciation at school. The teacher introduced us to classical music and played great symphonies for us during the semester it lasted. One day, she asked each student if they played an instrument. When she called on me, I said, “I play guitar.” She got a great look of distaste on her face, and said, “Well, that’s certainly a bad choice. You will never get anywhere playing a gee-tar. A gee-tar is a gutter instrument!”

That’s shameful, but a sign of those times, I guess. It must have hurt to hear that.

At first, it caught me off guard, and I was extremely embarrassed in front of the class and hung my head in shame. I was devastated. But then, I realized her vitriol was over the top and uncalled for, and she was being far too judgmental for no apparent reason. I decided to ignore her.

Damn right, too!

It was a strange experience, but I loved the guitar and would continue playing it. Her comments had an effect, however—a successful career playing guitar was further away than ever from my consciousness.

But how you proved her wrong…

After I began having success with hit records, I remembered that teacher once or twice, and I thought how wrong she turned out to be. I also recall thinking at the time that I wished I knew her name and address so that I could have sent her a Christmas card for a couple of years!

There was a music teacher at my school who actually encouraged me in my attempts to play guitar. She didn’t teach music theory or anything like that—she just played recordings of all kinds of music to open up our ears. She got me and my guitar-playing school chum to play at the school Christmas concert as a duo—my first public performance. I’d love to be able to thank her for encouraging me, but it’s so long ago and far away. Were you an ambitious and confident youngster, planning for your musical future?

I was ambitious when I was young, but with no idea of which way to direct that ambition. I wouldn’t say I was all that confident about many things during those years. I was very shy as a teenager, and I suppose that could have been interpreted as insecurity. I gained confidence as I grew older, began working in bands, and started recording.

When Moovin’ N’ Groovin’ went into the charts and got to number 70 or so, I felt very encouraged and quite confident that I was on the right path. With that mild success, I knew what I wanted to aim for when I went back into the studio to write and record again. On a March morning in 1958, Rebel ‘Rouser and Stalkin’ were the results of that newly found confidence.

Did it all unfold almost as if it was somehow destined to be?

Yes. I began working with local country musicians at 15 years of age at the VFW Hall, honky-tonks, dances at the Armory, and small beer joints around Coolidge, Arizona. But I was still going to school, and it was only a way of making a few extra dollars and having fun. I never dreamed I would be able to make a career of music in those days. And I recall wondering exactly what I was going to do with my life.

In early January 1954, my father met a local DJ named Jim Doyle. Dad mentioned his son played guitar, so Jim invited me out to the station to make a tape. I recorded a Chet Atkins tune I knew, and Jim played the tape early the next morning on his show. Coolidge being a small farming town, most everyone was awake at that time of day, and they tuned into the station…

That’s great, your dad rooting for you.

As a result, I received a phone call from a local country group, and I accepted an offer to work with them that coming weekend at a dance at the VFW.

That must have been exciting! What did that lead to?

At school, I met a kid named Jimmy Delbridge. We became friends and began playing and singing together at his house almost every day after school [Jimmy later shortened his name to Jimmy Dell]. Jim played piano much like Jerry Lee Lewis, but that was before we’d heard Jerry Lee. Jimmy just played that way from playing and singing at his Church. Then, one day in March of 1954, a new disc jockey came to our local radio station. His name was Lee Hazlewood, and it was his first job as a DJ after graduating from Columbia Broadcasting School in Hollywood. A school mate of mine, Ed Myers—who aimed to be a disc jockey—told me I should meet this new DJ. “He’s a very funny guy, and I think you’ll like him,” he said.

That, seen with hindsight, was an amazing and fortuitous encounter.

I could not have imagined at the time how both Lee’s and my life would benefit from our meeting—or that I would know Lee until he died in 2007.

He was an amazing artist and so right for your career at that point in time.

In retrospect, I’d have to consider all that “some kinda destiny,” as you suggested.

Do you now read music, or have any academic understanding of harmony and so on?

No. I had no formal education reading music, music theory, harmony, or any of it. I’ve often wished I could have had that.

Me too, Duane.

There is so much to learn and explore in music. I would have liked to learn to write out arrangements and not depend on arrangers and other educated musicians to do it for me. I could guide them and suggest how the arrangements should be—and I did—but I couldn’t write out those arrangements exactly the way I heard them in my head. Don’t get me wrong—I am not unhappy with what I did accomplish, and I wouldn’t change my history in music for anything. I love doing what I do. My life has been amazing!

There were just a few directions and ideas that I would have liked to execute—and be able to add to my musical repertoire—that weren’t possible due to my limited musical education. For instance, I would have liked to score movies, and be able to write the orchestration exactly the way I hear it. There’s no telling how far I could have gone, or what I could have done if I had been schooled in music. Teaching myself limited me to what I could listen to on the radio in those days, and there wasn’t a huge diversity to choose from back then.

Nowadays, young guitarists have so much information at their fingertips. It’s all out there waiting for them. Sometimes, I think it might be a little too easy. Having to figure out things on your own—almost in an information vacuum—helps you develop an individual, personal, and unique approach that becomes a musical signature of sorts. You really have to want it.

At the time I was teaching myself, there was only a Top Ten in either country or popular music. It wasn’t until 1956 or 1957 that the Top 40 came along, and not until June 1958 that Billboard magazine introduced the Top 100 chart. And the first week they published it, Rebel ‘Rouser was number 6 in the nation.

That’s quite an achievement. In the music scene surrounding your earliest bands, what sort of standard did local players attain? Did they have a formal musical education of some sort and read notation, or did they simply learn from listening to records and play intuitively by ear—as myself and many of my own generation did?

The local guys I played with first in Coolidge were not that accomplished. When I moved to Phoenix, I discovered some good players there. Some had taken lessons growing up, and there were even a couple of world class players, such as Bud Isaacs and Jimmy Troxel. Other than that, there were only a few guys who played fairly well. At the time, I thought they were quite good, but I discovered another, entirely new class of musicians when I began recording in Hollywood.

As a side-note, I have to tell you that since those early days, I’ve had the pleasure, the privilege, and the honor of playing with so many of the very best musicians in the entire world. When I was a kid, I could never have even dreamed that something like that would happen to me.

You have an absolute dream resume, Duane—one that so many of us guitar players are envious of. Let’s dig a little further into your roots. Early rock and roll had its foundation in country music and blues, with a little hint of jazz and western swing—all of which you must have been exposed to...

And just for the record, a lot of southern gospel from both white and black churches, as well. Elvis Presley and Sam Cooke were but two examples of the many artists who incorporated that influence into their mainstream rock and roll music.

I know that country music is close to your heart, but how about jazz and blues? Were you aware of the different threads that wove rock and roll’s still blossoming, colorful tapestry when you first began to make your own recordings?

I was aware of most all the different genres by the time I began recording, but hearing them and playing them are two different things. I couldn’t play jazz, but I did learn how to play blues in February 1958, while I was doing a weeklong rock and roll show in downtown Los Angeles. I only had one record out, Moovin’ N’ Groovin’, but I was booked on the show, and it was like going to college for me. I worked with Roy Hamilton, Don and Dewey, Thurston Harris and The Sharps, and other R&B; acts for the first time. I plunged head first into that culture.

Was that a kind of revelation?

I was very green, and it was quite obvious when I ran on stage to do my one song. But the Sharps took me under their wing and pointed out things that were extremely helpful, and by the end of that week, I was getting a fairly good idea of what to do on stage. We also went out together after hours. They took me down to Watts—to the 5-4 Ballroom on Central Avenue—where there was a big orchestra playing nothing but blues. They had a full horn section, four guitar players, keyboard, bass, drums, and percussion. The band also had a lead male singer, a female lead singer, and four background singers. There was a bandleader/conductor, and it was like the big bands of the 1940s, except they only played rhythm and blues. At the invitation of the bandleader—and at the Sharps’ urging—I sat in with the band for an hour or so, and that night, I learned how to play the blues.

Oh, man, how I wish I could have heard that!

Later, for my first few albums, I attempted to play different styles of music. I was pretty basic, funky, and crude with my playing in those days—I still am, though I’ve refined it somewhat—but it was all great fun to do. That was the beauty of recording albums in those days. You had to buckle down and work at recording something you thought might be a hit when recording a single, but when recording an album, we were free to do as we pleased—experiment with unusual ideas, try different types of music, and so on.

Who were the people you thought of as your contemporaries or peers at that time?

All the rock and roll artists were my contemporaries at the time. Bobby Darin, the Everly Brothers, Dion and the Belmonts, Sam Cooke, Brenda Lee, Connie Francis, Chuck Berry, the Platters, Jerry Lee Lewis, Jack Scott, Jimmy Clanton, Lloyd Price, Jackie Wilson, the Shirelles, Little Richard, Buddy Holly, Fats Domino, Ritchie Valens, The Big Bopper, Eddie Cochran, Frankie Avalon, Fabian, Annette Funicello, Dinah Washington, etc., etc., etc. We all worked together on shows at one time or another, and I became good friends with most of them.

What a fabulous roll call. Which of them impressed you the most and why?

Who impressed me the most? All of them—but each for distinctly different reasons. In those days, each artist was unique. Jackie Wilson wasn’t anything like the Everly Brothers, for instance, but I loved Jackie’s singing—especially his blues—and, at the same time, I loved the harmonies of the Everlys. There’s no more beautiful sound in the world than those two brothers singing together.

I loved their music, too. Hearing “Cathy’s Clown” played over the big Altec Lansing speakers in my hometown dance hall in my early teens was transcendental. I loved hearing so many great records in that environment: Buddy Holly, Eddie Cochran, Elvis, Fats Domino, Gene Vincent, Bo Diddley, Chuck Berry, Connie Francis, Brenda Lee...

At 16 years old, Brenda Lee could break your heart singing a sad song. She could also rock with the best of them on an uptempo song. She cut her first record when she was nine years old!

That’s pretty amazing! Sweet Nothings and Let’s Jump the Broomstick are just as exciting now as they were when first released—just timeless. How about that rolling piano-driven Fats Domino stuff?

Fats Domino’s New Orleans rock and roll was an entirely different thing again, but it was the best. As much as you can say anyone was the best when everyone is doing fantastic work and making such great music. No one is the best”—they are all different and great at the same time. My friend, Chubby Checker, had the biggest dance records of the 20th Century with The Twist and Let’s Twist Again (Like We Did Last Summer). On stage, we only heard Chubby do the Twist songs, but he could sing a ballad with unbelievable strength and sensitivity.

Again, I first heard Chubby’s records at the local dance hall. The Twist was a liberating dance for those of us who were usually holed up in the balcony near the Altec Lansings, too scared to jive.

Lloyd Price used to have a fairly extensive cast on stage with him, and they would all act out the song he was singing—such as Stagger Lee. It was amazing to see. Bobby Darin was the consummate performer, a great songwriter, and he later became an excellent actor. He didn’t continue doing rock and roll, but when I met him in 1958, his big hit was “Splish Splash”—as rockin’ a record as you could ask for. Chuck Berry’s playing, singing, and writing was superb. His songwriting is still being studied today because of the clever way his lyrics are so syncopated with his rhythmic melodies.

Chuck has influenced so many well-known English guitarists of a certain generation. The early Rolling Stones benefitted so much from him. Me, as well, when I was in a band called Group 66 in 1964. We covered lots of his recordings. Buddy Holly had an equally powerful influence...

Buddy Holly and the Crickets were fun to watch, as were Dion and the Belmonts. From the Bronx to West Texas, from Philadelphia to Phoenix, and all over America, it was all rock and roll with an unbelievable array of talent.

And a genuine Golden Age for the electric guitar. Electricity plus passion equals rock and roll.

I can safely say that we artists all loved our rock and roll. It was a happy music, and pure joy to jump in and put your whole body and soul into the playing of it. And we all loved and enjoyed each other’s versions of the music.

What other memories have stayed with you from that time?

Besides being impressed by my peer’s talents, I was also impressed by them personally. For example, while doing an Alan Freed show at the Brooklyn Fox Theater, I first met the Everly Brothers and discovered their father, Ike, was a thumbpicker along the lines of Merle Travis and Chet Atkins. And those great thumbpickers and the Everlys all knew each other—which impressed me mightily at that time. In that same theater during that same week of shows, I also sat in a dressing room one afternoon and jammed with Chuck Berry. I asked him what put him onto playing his style with the two notes at once that he constantly did. His answer was, “It gives me a heavier sound with more power—same as your playing on the bass strings gives you such a strong sound.”

I was also impressed with most all the artist’s niceness as people. They were all young—most beginning their careers in their teens, with a few in their early 20s. Just a bunch of kids really—all acting as grown up and professional as they knew how. I’m glad I knew every one of them. I loved them and I miss them to this day.

How about Elvis?

I never really considered Elvis Presley a peer. I always thought of him as being on a level of his own—much higher than the rest of us. That is, until I met him and spent an evening with him and Priscilla in Las Vegas in 1971. After talking with him, I realized he thought of all of us as his peers, and he loved our music. He treated me as an equal, and it was an amazing evening. I was able to thank him for what he did for me personally—and for all of us—by enabling us to have careers we might not have had if he hadn’t opened the door by defining rock and roll and setting the standard. He made it so popular and successful that it allowed the rest of us to jump on his bandwagon.

In the late 1950s when you were recording those iconic tracks for the Jamie label, how important was the producer’s role in the process? History tends to depict producers from the ‘50s and ‘60s as all-powerful Svengali characters, ruthlessly manipulating young artists to conform to the commercial marketplace. Your producer at that time was the now-legendary Lee Hazlewood. How did the relationship between yourself and Lee work?

As you know, things always appear different from the inside than from the outside, and much more important looking backward than they seemed going forward. First of all, Lee and I had become friends while he was in his first job as a disc jockey, and I was going to high school and singing and playing locally. We became friends and began experimenting with musical ventures. One of those early experiments was Lee writing and producing two tracks on Jimmy Dell and myself singing together. Nothing was ever done with it, but it was a fun experience for us. That was the first time for either Lee or me in a recording studio, and when we started working in the studio again a couple of years later, we just picked up where we left off and worked well together.

Was it a comfortable, natural process, or did you sometimes experience friction and conflicts of opinion?

The only occasional friction between us was when he would berate some of the musicians. The sidemen in Phoenix were made up mostly of country players who worked in honky-tonks six nights a week, and then showed up to help us make records at nine o’clock every morning. They’d be a bit bleary eyed and quiet, and occasionally they’d play a wrong note. Once in a while, Lee would jump on them for that and not let up. When it was getting to the point of really pissing off the musician, hurting his feelings, or embarrassing him, I would speak up and make a comment to lighten the situation. Lee would drop it, and the moment would pass.

He was an equal opportunity insulter, though. I’ve talked to musicians in Hollywood who were upset with his style of communication. I recall one well-known guitar player who was somewhat disgusted—and a bit surprised—when Lee addressed him as “guitar player number five” over the studio talkback.

There was one time early on, when he and I had an important disagreement and serious conflict regarding music. We had recorded a song called Mason Dixon Lion. Lee wanted it to be the follow-up to “Rebel ‘Rouser.” I said, “Absolutely not!” He looked at me in surprise and asked, “Why not?” I explained that it sounded too much like “Rebel ‘Rouser,” and I thought it would be a huge mistake to release a somewhat similar-sounding track as a follow-up. We went round and round about that for a while. But I was adamant, and he finally gave in.

In any event, my follow-up to Rebel ‘Rouser was decided for us when I played a song named Ramrod live on the Dick Clark Saturday Night Beechnut Show, which was an ABC Network TV show broadcast all over the country. The following Monday morning, the label received more than 150,000 orders for the record, so it became my third single.

I didn’t know of any Svengali type producers, although I did hear that word bandied about in conjunction with Nancy Sinatra and Lee in later years. But nothing could be further from the truth. Nancy was a very strong and independent young lady who didn’t take crap from anyone. And although she never traded on the fact, she was Frank Sinatra’s daughter, and for that reason alone, Lee wouldn’t have dared give her any grief. She was very aware musically, and she picked the songs she sang. Lee was inspired to write great material for her, and he worked with her to get those songs recorded like she envisioned, but he was no Svengali.

Is it possible he started that rumor himself to spice up the PR aspect of their working relationship, give himself more credit for their success, and possibly make for a more interesting story? It wouldn’t surprise me at all.

Not that he didn’t come up with great ideas and contribute immensely, but Lee was still prone to exaggerating his role in producing hit records and taking more credit then was due him for ideas that really belonged to his artists. For the most part, when I heard about such comments, it made me laugh.

Lee was easy to work with regarding music. He was untrained and uneducated musically, and he simply knew what he liked and what was going on in the charts. He was always open to new ideas, and the only thing he was firm and resolute about was the sound on the tracks. Lee knew exactly what he wanted to hear on each and every instrument and was uncompromising.

He had listened to hundreds of records while he was a disc jockey, and he analyzed the sound of those recordings on the good equipment that radio stations usually had in their studios in those days. He knew what bass sound he wanted, what drum sound, piano sound, etc., and he’d work until he got it. I believe he made better-sounding records than anyone else in the business in those days. He deserves all the credit for those old records of ours still sounding good and holding up fairly well today.

But your characterization of 1950s and 1960s “all-powerful Svengali characters, ruthlessly manipulating young artists to conform to the commercial marketplace” is a myth that’s way off the mark. Nobody had to manipulate me—or anyone else I knew in those days—toward a commercial marketplace. I wanted to get a hit as much as Lee did. That was always our goal from the beginning.

In England, back in the early ‘60s, there were producers and managers who created the artist’s entire persona and were kind of control freaks. I’m thinking of producers like Joe Meek and Larry Parnes. Of course, this was all done to target a mass audience, and it generally worked in terms of getting hit records, but quite a few of those artists later revealed themselves to have more under their hats—particularly when the later ‘60s counter-cultural rock scene emerged, and artistic-expression became fashionable.

There were no record companies back then who would allow us to record for the sake of “artistic expression.” It cost money to make a record, and if you didn’t make some money with the first effort, you seldom got a chance at a second one. Of course, no one knew for certain what constituted a hit. We just went with our gut feelings. I went with what was happening at the time, and what I thought the public might like—which, if I was in tune with them, was usually the same type thing I liked, multiplied a few million times over. It was music for people of my age and younger, and the so-called “Establishment” thought we were all rebelling. But we weren’t. We were just musically having the time of our lives. I loved making the music, and the world’s teenagers loved listening to it and dancing to it. It was as simple as that. It was new, it was exciting, and it kicked ass!

There was a certain amount of controversy attached to rock and roll though, at least as far as the popular press of the day was concerned.

I think those stories of riots were manufactured by the Tin Pan Alley music crowd. They were losing out on a great amount of revenue with the advent of rock and roll. They hated us, and the cry came right from their camp as they screamed, “Rock and roll will never last!” Now, there might have been a fight or two outside a rock and roll venue, but not riots. Still, they banned certain songs from being played on the radio by saying they were too explosive and a bad influence on the youth of the nation. My record, Rebel ’Rouser, was banned in Boston. Of course, to us, that was an inverted honor, and Lee and I were quite pleased. It was great publicity, and a dark validation of the fact that we had a successful rock and roll record.

Well, I’ve experienced a fair amount of that kind of mis-reporting myself over the years. Sometimes it’s been quite funny, other times damn frustrating, but once something gets into print, it multiplies like a virus.

If there was manipulation in those days, it took the form of changing the story after the fact. There is so much fiction written, and so many false stories told about me inventing my style of playing and developing my sound on the guitar, that if they were to be believed, you would think I had little or nothing to do with any of it. For example, years after I’d had my hit records, I began reading interviews where Lee said he had told me to play on the bass strings. According to his story, he had gotten the idea for my style from a piano player in the 1940s who played single-note melodies. The truth is, the idea for my style was totally my own. There was even a local Phoenix musician—whom I considered a good friend—who began to take credit for teaching me how to play guitar, and for coming up with my sound. He even claimed to have played my parts on several of my records! All his claims were so obviously false that it really pissed me off at the time. But I eventually wrote it off as an example of the damage caused by his lifelong battle with alcohol.

I understand that you have produced other artists. Do you find it an enjoyable experience? What would you say defines your personal approach to production?

Then—as now—I believe the producer’s role is to listen carefully, sense where the artist is going, and help them make his or her own record. As a producer, you’re there to keep the artist from going off the road with some of their wilder ideas, and if they get jammed up, to help untangle the mess. Along the way, a producer will shape the direction of the project by suggesting ideas to the artist. A producer’s job is to set the session up, take care of business necessities such as the budget, book the studio, pay the musicians, etc., He also coordinates the sound with the engineer, guides the musicians in the studio, and is there to take the pressure off the artist so that he or she is able to be creative, and to feel free to perform without worrying about anything else.

What was a memorable production job for you?

I produced Phil Everly’s first solo album. All I did was to make it as easy as possible for him to do what he wanted. He already knew how to make hit records. He’d written most of the album, but he did agree to do one outside song I suggested for the project. I was not about to ask him to sing harmony with himself, but when he suggested it, I was very pleased. When he actually did it, I was over the moon! He has such a great voice, and he is without question the best harmony singer in the past century. He just thinks a bit differently than all the rest, and executes his harmony better than anyone.

How did the role of producer sit with you?

I have to say that I probably would have enjoyed it much more if I’d produced a hit record. I thought I might get one with Phil. I asked both RCA and Phil’s management repeatedly to release the song I’d brought to the project as the first single. They all refused me, so that was that. But there was a group in England who told me later that they were listening to Phil’s album because they were fans of both of ours, and when they heard that song, they felt that it must—absolutely must—be the single from our album. When they found out it wasn’t, they went right into the studio that night and recorded the song. The group was the Hollies, and the song was “The Air That I Breathe.” After they had sold two million copies, Phil called me, and said, “Well, you’ve been vindicated.”

Then, I produced three or four tracks for Waylon Jennings and the Crickets, but they weren’t intended to be singles, and they didn’t impress anyone. So I went back to work on the road, went on to have another hit record of my own, and I lost interest in producing records.

The guitar sound you originated—which gave birth to the term “twang”—is very much a Duane Eddy trademark, and still instantly recognizable, despite being adopted, referenced, quoted, and appropriated in the playing of many other guitarists of subsequent eras.

It’s often said that imitation is the most sincere form of flattery, and I am always completely flattered when I know that someone was influenced by my sound. I love hearing others play that sound, and all is right with the world when a certain song cries out for the sound to be there, and it is there—even though I didn’t play it myself. And, sometimes, especially since I didn’t play it myself!

I have also often noted with wry humor that plagiarism is the sincerest form of flattery, but I don’t mean it. There was only a couple of times when I was really plagiarized, and that was in the 1960s when a New York City guitar player named Al Caiola copied my sound as best he could and had a few hits. He did songs like The Magnificent Seven, The Bonanza Theme, and so on. I didn’t find it flattering, and I didn’t feel they were great records, but they did very well—mostly on the strength of my records being so popular at the time.

You’re very much what I would consider to be a “musical stylist,” in that there seems to be a relatively consistent musical design or motif at work throughout your career. However, albums such as Songs Of Our Heritage showed that there are other facets to your playing and your creative sensibility. As commercially successful as it has been for you, have you ever felt, no matter how slightly, a little frustrated or musically fenced in by the “Twang Thang?”

I’ve never thought of it that way. That sound on the guitar is my voice. If I were a singer I couldn’t change it, and it doesn’t hold me back from doing any idea I can think of. When I deviated from the bass strings of the electric guitar on several occasions, I did so in response to an idea, a thought, or a wish to explore something entirely different than what I usually do.

I imagine a guitar player of unusually great skill and diversity might find themselves feeling “fenced in” by perceived limitations of the “Twang Thang.” But why would they be doing something like that anyway? Every guitar player has his or her own approach to the instrument. I have discovered that it is extremely interesting and challenging to fit my sound and style of playing into different settings, and make it seem as though it belongs there. I’ve worked with small groups and orchestras. I’ve done pure country music—such as my Twang A Country Song album with Buddy Emmons, the world’s greatest pedal-steel player—and I’ve also recorded a few tracks of Hawaiian music with Jerry Byrd.

I’ve done Blues and approached Jazz and Dixieland. I recorded an album of Tin Pan Alley songs of the 1940s with a big band. I’ve put the Twang into weird, avant-garde sounds such as The Art Of Noise. And I’ve worked with different producers, from Lee Hazlewood, Jimmy Bowen, and Dick Glasser, to Tony McCauley, Ann Dudley, Paul McCartney, Ry Cooder, and Richard Hawley with Colin Eliott. They all introduced their individual stamp on what I do, but, through it all, I believe I’ve still managed to maintain the integrity and the character of my sound.

That’s an important point. I’ve placed my own playing in all sorts of contexts, but people always say that, no matter how outside or experimental things might get, my playing is recognizable. I’ve sometimes wanted to sound like one or other of my heroes, but it still somehow ends up sounding like me. It seems we’ve got no choice in the matter!

I’ve always attempted to push the envelope—or at least give it a nudge one way or the other. I like exploring different textures on tracks in the studio, and different types of arrangement ideas. For me, it’s not just playing the instrument, it’s also making the record. I guess a better way of explaining it is that I don’t write or arrange songs as such. Instead, I think of it as writing or arranging records. My sound is the common denominator that pulls all the threads and knits them together. This allows me to go in any direction I can think of, and still have a recognizable product when I’m finished. As a result, I have never felt the slightest bit frustrated or musically fenced in. As long as I am exploring new territory, trying new ideas, and playing simple-sounding licks that are sometimes quite complicated and difficult to execute, I can love both the challenge and the results.

Les Paul and Chet Atkins are two other hugely influential guitarists, and I know that you admired their playing. Your recordings of Lover and Trambone were, I’m guessing, an affectionate nod to Les and Chet. But these tracks beautifully illustrate your gift for playing in the broader context I was referring to in my previous question. Would an album built entirely along similar lines ever be a possibility?

You are right. Those songs were my attempts at tributes to Les and Chet. I am not a smooth thumbpicker, though, and I can only approximate what Chet does. It’s the same with Les. I was totally impressed with Jeff Beck’s Les Paul tribute on the Grammys right after Les passed away. He and [vocalist] Imelda May did an astounding job of sounding like Les Paul and Mary Ford’s recording—not an easy feat to accomplish!

As for an album of mine built entirely along similar lines—I rather doubt it. I’d like to, but I don’t know if or when I’ll have the opportunity to record again. Though it’s always a possibility, I suppose. Only a couple of years ago, I certainly never expected to be recording with Richard Hawley and his Merry Men in Sheffield. So I guess that shows that anything can happen. But I have no idea whether Road Trip sold enough to encourage the record company to come back for more. But if someone asks me to record, I’m ready, willing, and still able.

Going at this from a different angle, I think it would be fascinating to hear your signature sound and style within an experimental, more abstract framework. You’ve made some very contemporary-sounding recordings over the years—I’m thinking of your collaboration with Art Of Noise in particular—but I wonder if there’s an album of dark, drifting, deeply atmospheric, improvisational, haunted, almost ambient music lurking in some mysterious corner of your soul?

Good Heavens, I hope so! Your description sounds so great, it makes me want to stop writing this, pack up my guitar and amp, and head for the studio right now! Because I think you are right—I have always had ideas such as you describe floating around in the back of my mind. And I would love to give that type of thing a try. Actually I think Richard and I approached somewhat close to your description with Desert Song on the Road Trip album. It had some of those elements in that it was drifting, atmospheric, and improvisational. But I’d still like to have another go at doing a track with all the elements you mention. I believe I could do haunted and dark, as well, and I would certainly love having a go at it.

I’d love to hear that, Duane!

I thought it sounded as though you are doing that sort of thing on some of the tracks on your albums, Bill. Your playing is gorgeous, and you really take us on an atmospheric and mysterious journey. Perhaps you and I could get into the studio at some point and do a track or two like that.

I’m deeply flattered that you’d consider such a thing. I would love that. It would certainly be a dream come true for me! There’s a “golden chain” of unique guitar players, which stretches from players such as Charlie Christian, Eddie Lang, Django Rheinhardt, and Merle Travis through Les Paul, Chet Atkins, yourself, and others—right up to the present day. Do you feel that new ground is being broken by the current crop of players? Or is it more a matter of younger musicians mainly revisiting older styles and attitudes?

I often hear new, young musicians who are fantastic, and I believe there will always be someone who comes along and breaks new ground with a guitar. I’d bet they’re doing it right now, but we just haven’t heard them yet. Among them are many who are revisiting older styles and attitudes, and that is, ironically, a great way to break new ground. You revisit the old established sounds and styles, and then with those influences in your subconscious, you work to invent your own style or sound. That’s one of the ways it can be done—taking elements from here and there, blending them together, adding your own ideas, and thereby creating something new and fresh. Something not heard before, but with just a tantalizing hint of familiarity.

Another way of doing it is to begin with a totally clean slate, and create something new and different that comes from within your brain. Something you’ve never heard or thought of before, and no one else has either, as far as you can tell. That’s a bit more difficult to do, but immensely rewarding and satisfying to accomplish.

Unfortunately, it’s more difficult these days to get noticed, played on the radio, and get to the top with something original and new. Although with the advent of the Internet and YouTube, there are new ways opening up for the public to find the artists whose music is exactly what they want. As it always has, the music business evolves and changes with the times. One group I like very much, the Black Keys, are doing great and making fans all over the world. Their success certainly proves that it can still be done.

Two of my favorite contemporary guitarists are Bill Frisell and Fred Frith. Their approach respects and upholds elements of tradition, whilst simultaneously looking to a more radical future. Their playing is complex, fearless, and beautiful, but perhaps not what people would consider mainstream. What I’m trying to say is that the guitar—whilst being the most popular instrument of all time—is capable of a widescreen range of sounds and moods, yet relatively few players are given credit for getting “out there” into realms that are considered avant-garde.

I’m curious as to what your take might be on this sort of thing. After all, you were pushing the sonic envelope in a very fresh and exciting way on those now-classic recordings. What, for instance, were your thoughts on Jimi Hendrix when he first came on the scene? Did you relate to him and his music? Are you still open to wild guitar adventures?

I am always open to wild guitar adventures! When I was a young man and constantly exploring new things, I was able to see and hear great players like Barney Kessel and Howard Roberts. I saw Segovia at the Town Hall in New York City. I went to see flamenco players at clubs in Los Angeles. I saw B.B. King play live, as well as Chet Atkins and other great players and guitar heroes of mine. I even hired some of them to be on my recording sessions in Hollywood.

But I never saw Jimi Hendrix—except on TV, and I certainly loved that. He had to be one of the best—if not the best—showman with a guitar of all time. I wish I could have met him, and felt his attitude and charisma in person. I believe I would have liked him a lot. Apparently, according to all his friends from his teenage years, he was a huge fan of my records—which was great to hear.

I agree with you about Bill Frisell and Fred Frith. And, no, I don’t believe they could be considered mainstream. That’s not to say that either of them couldn’t come up with something that would appeal to the mainstream. I remember that guys somewhat like them back in the ’50s and ’60s occasionally did something unusual that would make its way into the mainstream and open up new worlds to the music public. Antonio Carlos Jobim introducing the world to bossa nova in the 1960s comes to mind.

Let’s talk about specific guitars a little. Throughout the years, you’ve played the three big ‘Gs’—Gretsch, Guild, and Gibson. But for many fans—myself included—the Gretsch 6120 will always be the ultimate Duane Eddy guitar. You’ve recently returned to Gretsch, who have issued a new Duane Eddy signature model. Did you have personal input into the design of this instrument? How closely was it based on your original 6120?

It is very closely based on my original 6120. Fender’s Master Builder Stephen Stern came to Nashville, and he measured my original guitar and studied it carefully before he went back to California and built the prototype. He discovered several differences between the 1957 Gretsch 6120 and the ones they make today.

In what way?

First, the body on the ’57 was an eighth of an inch deeper. Then, the neck was much narrower, and the binding was wider. Stephen also added bracing inside to soak up some of the feedback those guitars can produce when put through a powerful amp. I also made a few minor changes. I had the idea of putting longer pins in the Bigsby to make it easier to change strings. Anyone who has ever changed strings on a Bigsby knows that it is extremely difficult to hold the string on the pin while you attempt to thread the other end through the tuner key.

I solved that a few years ago by having my luthier friend Mike McGuire lengthen the pins on the Bigsby. It works wonderfully, and it solved that irritating little problem nicely. So I asked that the pins be lengthened on all the Bigsbys on my signature model, and Fred Gretsch complied. I also asked for a Tru-Arc bridge to be a feature, as it gives the guitar a bit more sustain and a somewhat clearer tone—or more twang, if you like.

How about the pickups? Your original guitar used those now classic DeArmonds.

The pickups on my old ’57 are fading a bit. I have to turn the amp up more to get the full sound from them. But the new guitar with the DynaSonic single-coil pickups that were modeled after the DeArmonds on my original ’57 Gretsch—and with the same maple body—sounds exactly like my old original Gretsch. It’s like having the ’57 back all new again! It plays the same and sounds the same as my original. The minor changes I made only improve the new guitar.

If you want to hear what I mean, check out Road Trip. You can hear the sound hasn’t changed, and yet it was recorded with the new signature model. That album is the first thing I’ve ever recorded that I didn’t use the original ’57 on. Except, of course, the tracks where I used the Danelectro bass-string guitar, or an acoustic or gut string.

It’s only in more recent years that I discovered Because They’re Young was actually recorded on a Danelectro Baritone, rather than on a Gretsch archtop. Can you recall which other of your classic tracks were done with the Dano?

Mine was the Danelectro bass-string guitar. I believe they tune a baritone guitar to a B, whereas the Dano bass guitar is tuned to E, but one octave lower than a regular guitar. I recorded most of my third album, The Twang’s the Thang, on the Dano. I’d just discovered and bought one not long before I began working on that album.

It certainly suited those tunes.

At the time, I felt the Dano might have been designed especially with me in mind. In retrospect, I don’t know that it was, for I never got to meet [Danelectro founder] Nate Daniel to find out if he’d had any thoughts of my sound when he came up with the idea for the guitar. But it works well for me, and when I have to play in a key that doesn’t suit my sound as well on the Gretsch, I get out the Dano and use that. Just a few years ago, I used it when I worked with Hans Zimmer on the soundtrack for Broken Arrow, starring John Travolta and Christian Slater. The music Hans had written for the soundtrack was in the key of C. For the ominous low notes needed, I had to go to the Dano to get them to sound the way I liked to hear them in that key.

Forgive me, but the following is, I guess, real geek stuff. When I was 11 years old, I made a cardboard replica of your Gretsch 6120—which I copied from the photographs on the covers of the Especially For You and The Twang’s the Thang albums. I painted this cardboard guitar red, as that was how the color came across on the album sleeves. Of course, I later discovered that 6120s were actually orange. Did your original Gretsch have more of a red tint, or was that an illusion created by the printing process back then?

That is a good question—nothing geeky about it at all. Well, maybe a little geeky. But aren’t we all a bit geeky as kids? Nobody grows up already being a wise old man. Back to your question, the guitar is orange, but it always photographed as red. Even with the digital cameras of today, it still tends to photograph more red than orange. The new signature model seems to do the same thing, and pictures I’ve seen of me playing it make it look more red than it actually is. I think if you put the guitar next to another guitar that was actually painted red, it might show up as orange, but I haven’t tried that yet.

Before you got your original Gretsch 6120, you played a Gibson Les Paul. What was it that made you switch guitars? Was Chet Atkins’ endorsement of Gretsch an influential factor?

No. Chet’s endorsement had nothing to do with it—nor did the weight of the Les Paul or the sound/feel of the Gibson or the Gretsch. I simply wanted a guitar with a Bigsby vibrato on it. Of course, when I first held the Gretsch in my arms and played a few notes I fell in love with the neck. It still is the best I’ve ever played. But my reason for going to Ziggie’s Music Store in Phoenix that day in the spring of 1957, was to look at a guitar with a vibrato on it. I just had a feeling it might be fun to have, and might work out well for me. Was I right?

You certainly were! The vibrato arm also helped define Hank Marvin’s sound back in the 1960s—though you both used it in your own individual ways. It’s an essential item for me, too. What amps were you using on those early albums? I seem to recall Magnatone and Standell amps being mentioned in connection with your work. Was that the case? What are you using these days? I saw two huge Fender speaker cabs at your concerts in the U.K. a while back. They looked like bass cabs with 15" speakers.

When I first bought my Gibson in a hardware store in Coolidge, Arizona, I also bought a homemade amp from a local guy who made them out of orange crates with chicken-wire grill. It served for a year or more until I’d earned enough to buy a new Magnatone amp. I played through the stock amp for a few weeks until I had it modified by Buddy Wheeler and Dick Wilson, who were doing modifications for musicians in Phoenix. They would modify the power plant to over 100 watts and exchange the two 8" speakers—Jensen, I think—for one 15" JBL speaker and a tweeter. Then they covered the amp in black Naugahyde with a white grill cloth, and it looked great. And, of course, it sounded great. They had just finished doing my amp when I got my new Gretsch, so I was set. I went to work that night a happy man. Oh, how great it all sounded to me! I had unlimited power and clarity. It was a wonderful experience.

A couple of years later, I had the opportunity to A/B my amp with a Standell at Manny’s Music in New York City. No contest. Standell was supposed to be the best, but my reworked Magnatone blew it away. I had more level, more power, more clarity, and I could hit high notes or low, with more force than I could on the Standell. On the Standell, if I hit a note that hard and loud, the amp would break up. Don’t get me wrong—it was a lovely amp, but not a patch on mine.

I’m pleased to hear that you are working with ace guitar tech Gordon White when you tour the U.K. You couldn’t be in better hands. Gordon is an absolute treasure, and he has been my personal choice of “guitar-fettler” for several years. Gordon told me that he’d made you a pedalboard for the UK concert dates, and that you’d never had such a thing before. I was greatly intrigued by the idea of Duane Eddy with a pedalboard, and I wonder if you could tell us what resides on it.

I absolutely love Gordon White! Everything you say about him is true 100 times over. He’s the best I’ve ever seen. He’s a mind reader. Just when I have any kind of a problem and think about looking around for him, I turn and there he is beside me, already working on the solution to whatever the problem might be. He’s totally amazing. The pedalboard he made for me is extremely minimal. It has my Dunlop tremolo, a tuner, and a Nocturne Dyno Brain boost pedal.

Being a successful instrumentalist in pop and rock isn’t an easy accomplishment. Were you ever under any pressure to sing, as well as play guitar?

Thank you. It’s a strange accomplishment. As Willie Nelson says, I was “one in a row.” Conan O’Brien once asked me on his show, “Duane, you’ve been in this business for many years now. What do you consider your greatest contribution to music?” I answered, “Not singing.” I never felt that I had a good voice for singing. When I was young, this frustrated me a lot, so I took it out on the guitar.

Not only did you take up the instrument at a very early age, but your commercial success came early in life, too. The music business is notorious for unfairly exploiting artists. Nowadays, there’s much more available information to forewarn young musicians of the pitfalls and rip-offs that might eventually hurt them. When I started my professional career, I was a complete innocent, and, like so many musicians, I later suffered the consequences. I’d be interested to know what your own experience of the industry has been.

Believe me, it would ruin your entire day to learn about all the crap I went through. I fell in with a nest of snakes and a den of thieves, and I didn’t even realize it for several years. That was probably a good thing, because I just kept going—even though I subconsciously felt something was very wrong. I couldn’t put my finger on it, but I kept thinking that this kind of life should have been better than it was turning out to be. Years later, I found out exactly what the labels, agents, management—and even some of those folks whom I thought of as good friends—were doing to me. But that’s another story for another time.

Well, I can empathize with you there. We can exchange horror stories next time we meet! Do you have any words of hard-won wisdom to pass on to younger players?

As pedal-steel player Buddy Emmons said in an interview when asked the same question: “Not one damned thing!” Later on, I asked him why he said that, and he explained, “Every young musician has to make his or her own mistakes and learn the ropes themselves to really get educated. If I gave them advice, they would not understand much of it, and probably wouldn’t believe any of it.”

I’ve pretty much adopted that credo for my own. Young kids don’t want to hear how the old Geezers did it. That was way back in the Stone Age. They live in more modern times now, and it’s all new and different from what the old folks went through—or so they think. However, when I am asked by a young artist who sincerely wants to know, I give them this general advice, which is to find their own style, do it with authority, and let their emotions show through when singing or playing. I learned to do that by listening to country singers when I was growing up, and it worked out very well for me.

Perhaps this is a tender subject, but although we both remain passionate about music and guitars, we’re older now. And yet, I noticed while watching your live performances a couple of years ago, that you have managed to maintain a wonderful sense of physical stamina and mental focus in your playing. What’s the secret? Do you have a special pre-show regime? Do you follow a healthy lifestyle at home? So many rockers fall foul of one thing or another. How have you maintained a distance from such negative influences?

No pre-show regime. The only thing I consciously do is to try to avoid stress. I have a wonderful group of people around me to help me do just that. My wife, Deed, is my number-one partner in the team, but there’s also my friend and manager Graham Wrench, my friend Richard Hawley, and our musician friends Jon Trier, Colin Elliot, Shez Sheridan, Dean Beresford, Paul Corry, Tina Peacock, and Louise Thompson. Also Graham’s assistant, Tilde Bruynooghe, is on top of everything that’s going on.

And, of course, the man you mentioned earlier, Gordon White, and also our soundperson, Mike Timm. These are all the most professional, hard-working, and most talented people I’ve ever had the pleasure of working with. They seem to turn up at the most advantageous times, so whenever there is a problem, I soon discover it’s being handled. All I end up having to do it seems, is to strap on my guitar and walk on stage. And for all of you musicians who may read this and experience a twinge of envy or jealousy—just remember it took me nearly 50 years to finally fall into this situation!

As for my health, I finally gave in and went to the doctor. As I’ve always feared, they immediately immersed me into their system. They found enough wrong with me that I had to quit smoking and change my diet. I lost 30 pounds and I have to exercise, so I am now disgustingly healthy.

As for the negative influences you asked about, I’ve been lucky. I never cared much for the taste of liquor and beer—except I do like English beer—and I was always scared of drugs. So I’ve been lucky—I never succumbed to negative influences. I certainly understand the temptation, and it is very conducive to a musician’s lifestyle.

Then, there’s the romantic image of the great musician who will play even more amazing stuff when he’s high or strung out on drugs. I never believed that myself. I believe that if you “get out of it” and go on stage in front of an audience, you not only look like you’re a bit demented, but your adrenaline conflicts with the alcohol or drugs in your body and messes your mind up. Yeah, you might lose some inhibitions and play a few things you wouldn’t have played, but you probably could have mentally worked on losing your fear and played even better stuff sober.

All the great musicians I’ve known did their best work while sober and straight. The great ones save the partying for when they aren’t working. Some didn’t, of course, but most of them are dead. I never understood that mentality. A banker, a firefighter, a bus driver, or an accountant would never go to work stoned out of their minds. Why do musicians think it’s a good idea to get loaded just to go to work?

I was so pleased to see, when we met, that your gracious wife, Deed, seems to be a pillar of strength for you. My own wife, Emiko, likewise provides the kind of emotional support that I very much rely on in my public role as a musician. Has the fame and adulation you’ve generated over the years been easy to deal with, or has the presence of a strong and loving wife made the situation more comfortable than it otherwise might have been?

I never took fame seriously, or let it go to my head or make me conceited. I’ve always considered myself a professional doing my job, just as any other professional does. The fame is great for procuring more work, and who finds fault with adulation? But Deed is a source of great strength to me, and without her I’d be lost. She makes me laugh and cheers me up when I’m down, and I’ve learned things from her I never would have known otherwise. She’s an intellectual partner, and, in fact, an equal partner in everything I do. She is invaluable when it comes to organizing our day, sorting our schedule, and making sure that I get to see old friends and fans while out on tour. She’s the love of my life, and I can’t imagine living without her. She has made everything happier and better in my life.

Your recent album, Road Trip, was recorded with Richard Hawley’s band in Richard’s Sheffield studio in South Yorkshire. For me, as a Yorkshireman, Phoenix seems a much more glamorous and exotic location for recording than Sheffield. I actually performed at Phoenix’s Celebrity Theatre a few times back in the 1970s. When I was a teenager, the idea of Duane Eddy making a record in Sheffield would have been unthinkable, and yet you seem to have enjoyed the experience tremendously. Are there things that link Sheffield with Phoenix in some way?

One similarity that’s not apparent at first is the landscapes surrounding both cities. A few minutes drive out of Phoenix, and you are in the Arizona desert—an arid land of big sky, the Superstition Mountains, Saguaro cactus, and beckoning trails. A few minutes drive out of Sheffield, and you are in the Yorkshire moors with canyons leading down into beautiful pastoral valleys with flowing rivers, forests, and charming ancient villages. The scenery in both places couldn’t be more different, but also couldn’t be more inspiring. I’ve always had the idea that nature’s beauty reflects itself in music, and my music was certainly influenced by the southwestern desert. I draw musical inspiration just as much in Yorkshire—in the spectacular hills, mountains, and moors around Sheffield—as I do in the Arizona desert, though in a different way.

Recording at Richard’s Yellow Arch Studios was a treat for me. It’s the first time since the 1960s that I have written and recorded an entirely new album in the studio with live musicians. Recording in this manner zapped me right back to the early days at Ramsey’s studio in Phoenix. Other similarities that link Sheffield and Phoenix are the attitudes among the musicians. When I recorded in Phoenix in the early days of rock and roll, we figured we had an idea of how it was done in the big time in musical cities such as Los Angeles, New York, and Nashville. Actually, we didn’t have the slightest clue. But the desire, the love of the music, and our naive ideas of how we thought it should be, carried us through.

Along the way on our musical journey, we learned. There was a naive sophistication that carried us through. In other words, we actually knew what we were doing, but we didn’t realize it. Because we were not in London or New York City, we weren’t supposed to know what we were doing. I came to believe that when no one tells you that you can’t do something, there’s nothing to stop you from doing it. So we were able to make records that successfully competed in the world market.

You have created an enduring legacy for guitarists of all generations. Do you feel it’s enough? Or do you still have the hunger? I don’t mean in terms of fame or celebrity, but in that old hard-won, “love it/hate it,” inch-by-inch advancement that keeps us opening our guitar cases and staring at the instrument as if it’s an entirely new, beautiful, and yet scary thing?

Thank you for the kind words regarding “enduring legacy,” but I never set out to do that. In the beginning, I was just having a great time playing honky-tonks and bars to make a living. On a different scale, I’m still pretty much doing the same thing today.

As for it being enough, I don’t think any of us ever lose that hunger. Playing guitar gets in our blood and seeps into our soul, and we never stop learning new things about it. That is a lovely way you put it when you suggested the guitar being “an entirely new, beautiful, and yet scary thing.” It is also a comfortable and familiar friend that is not only the tool we work with, but can even be used as therapy on a bad day when you feel down and out and nothing seems to be going right.

Playing your guitar will take your mind off your troubles, and help to get you on a path to feeling better again. And, in the process, you might just accidentally come up with that one idea you’ve been looking for.

Originally published in the January 2013 issue of Guitar Player magazine.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

"Jaco thought he was gonna die that day in the control room of CBS! Tony was furious." John McLaughlin on Jaco Pastorius, Tony Williams, and the short and tumultuous reign of the Trio of Doom

“It’s all been building up to 8 p.m. when the lights go down and the crowd roars.” Tommy Emmanuel shares his gig-day guitar routine, from sun-up to show time