As a working guitar player, I’ve gigged in backyards, dive bars, discos, hockey arenas, pizza parlors, symphony halls, and living rooms, and on tropical islands and cruise ships. I’ve performed wearing everything from ripped-up rocker jeans, to tuxedos, and cowboy hats.

And I’ve played with rock bands, soul bands, jazz ensembles, Afro-funk groups, garage bands, legacy acts, DJs, orchestras, and rappers. In other words, I have messed around with a range of guitar styles. And if you’re like many GP readers, you probably have too.

But if you’ve never tried out the Eddie Van Halen guitar style – and what a multifaceted style it is – I can tell you something that the rest of the guitar galaxy already knows: It’s fun.

How much fun? Well, on a good night with a good tone and a set of power tubes running white-hot, playing a Van Halen song like “I’m the One” with a great bassist and drummer is an absolute thrill ride.

Being a Van Halen superfan since the early years of the Reagan administration, I am going to try to win over these EVH naysayers – all three or four of you

If you can get those guitar parts down even semi-accurately and, more importantly, perform them with even a smidgeon of the groove the man who wrote them did, get ready for a huge adrenaline rush: You’re going to feel like Daenerys Targaryen riding a dragon, Laird Hamilton surfing Jaws, or Luke Skywalker blowing up the Death Star.

But that particular song represents just one facet of the Van Halen sound – specifically, the high-revving, joyriding-in-a-stolen-Ferrari side. The truth of the matter is, Eddie Van Halen’s talents went far deeper than most music fans even realize.

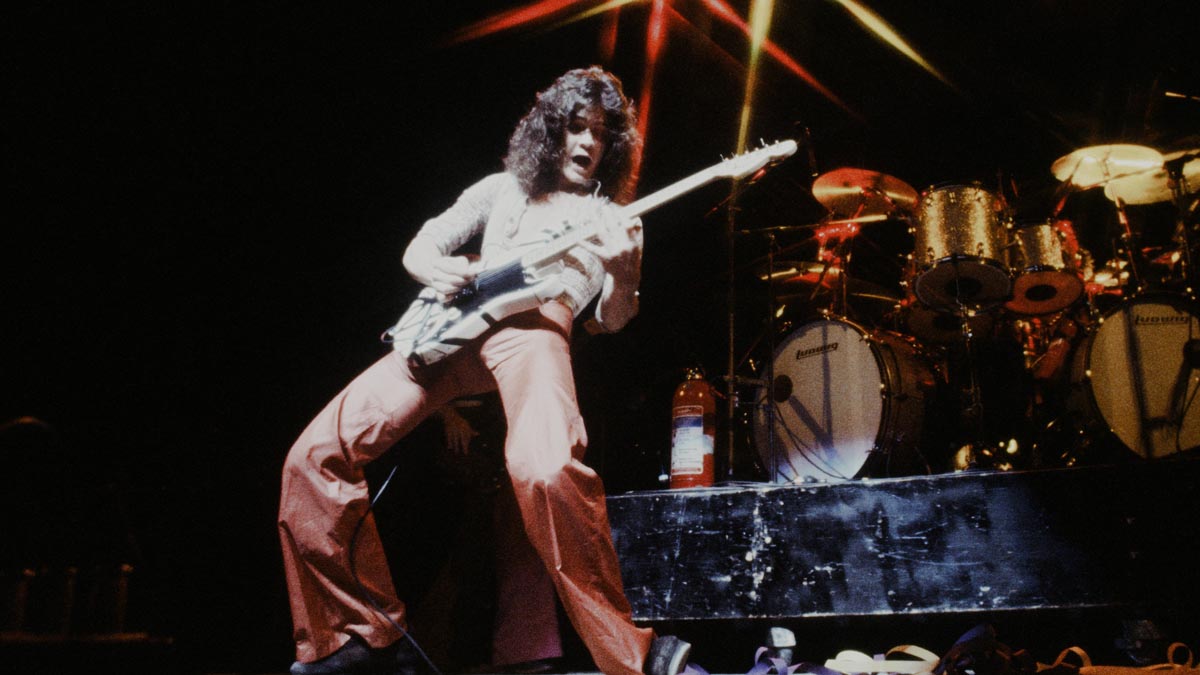

When it comes to remembering Eddie Van Halen, the indelible image most of us will carry going forward is that unforgettable spectacle of the inventive kid from Pasadena on a giant stage, playing a greasy red, white, and black candy cane he called Frankenstein, and smiling as he melted faces by the thousands.

But although Van Halen certainly did play in huge venues, with monster P.A. systems and lighting rigs you could probably see from space, Eddie never needed all that rock artillery to blow your mind. The simplest testament to his incredible guitar playing may be the off-the-cuff virtuosity he displays on that inimitable nylon-string moment we know as “Spanish Fly.”

Yet, today, as I write this, less than a week after Eddie Van Halen’s death – even as tributes to the Dutch-born guitar prodigy pour in by the thousands from guitarists all over the globe – there are a handful of detractors posting tepid or even snarky appraisals of EVH’s contributions to the guitar lexicon, saying things like, “I just didn’t get his playing,” or “Overrated.”

Normally, such proclamations wouldn’t ruffle my feathers. This week, however, it’s personal. Being a Van Halen superfan since the early years of the Reagan administration, I am going to try to win over these EVH naysayers – all three or four of you.

It’s not because I seek confrontation but because I suspect most of you haven’t delved very deeply into Eddie Van Halen’s music. And if I’m right, wow, are you missing out. If you don’t believe me, allow me to consult a certain Rock and Roll Hall of Famer I know.

“I honestly don’t believe anyone could or ever will be able to touch Eddie Van Halen,” Journey lead guitarist Neal Schon says. “His raw energy and outside-the-box creative genius was just staggering. He had a sound and knew how to get it. And he knew how to write songs that fit his playing. Everyone knew him as an excellent lead guitarist – and he was indeed one of the best – but his sense of rhythm was just insane. That pocket, man!”

Schon’s perspective is one that we should respect, not only because he’s one of the world’s preeminent rock guitarists but also because he had the thrill – or should we say the challenge? – of having a 23-year-old Eddie Van Halen open for him in 1978.

He is one of the greatest rock and roll guitar players of all time, right up there with Jimi Hendrix

Neal Schon

“It was like getting your ass kicked every night by the best sword-swinging sushi chef in the land,” Schon told me for a 2008 GP cover story. “I had seen a lot of guitar players by then but had never seen anything like Ed. He is one of the greatest rock and roll guitar players of all time, right up there with Jimi Hendrix. And he had extreme fire and loose abandon on that tour.

“Van Halen were touring their first record, we were touring our first record with Steve Perry, and Montrose was in the middle slot. I told Ronnie [Montrose], ‘Man, I’m glad you have to follow that and not me!’”

Which brings me back to the haters: Ever notice that most guitarists who criticize EVH’s playing have never truly learned to play a single Van Halen song? Let’s fix that.

First of all, to any devoted guitarist out there who doesn’t “get” Van Halen, I understand that there is a range of possible reasons for that. For instance, maybe you were put off by the band’s volume levels, or even by the group’s fans.

I certainly was when, in the sixth grade, my friend’s obnoxious older brother came into the room blasting “Unchained,” proclaiming “Van Halen kicks every other band’s ass.” Or, let’s be real: Maybe you were put off by Van Halen’s lead singers.

Whatever the case, let’s avoid the vocal tunes for a moment and start things off with a simple challenge: I dare you to put on some headphones, close your eyes and take in the pleasing melodic ricochets of Eddie’s transcendent 1982 instrumental “Cathedral.”

If you don’t like this piece, you don’t like Mozart, you don’t like Bach, and you probably just plain don’t like music. But if you do dig the perfect ear candy of “Cathedral,” I have good news for you: You don’t have to be a guitar virtuoso to play it.

If you can hammer a few notes with your fretting hand and use your guitar’s volume knob to swell into each pitch, then, for the low price of playing in time with a dotted-eighth-note delay, this magical guitar piece can be yours.

You can even rock out on it through overdriven amps, as Eddie often did live (check out the five-minute mark of “316” on Van Halen Live: Right Here Right Now).

Now, before we continue this EVH listening party, there is a recurring piece of rhetoric that needs to be finally snuffed out. I’m talking about that moment when, after someone commends Eddie for being a great guitarist, someone else swoops in with, “Yeah, well, he wasn’t the first guitarist to tap. Steve Hackett invented tapping in 1971.”

I take issue with this response on two levels. First, that’s your takeaway from the Van Halen legacy? That Eddie was “the tapping guy”? If that’s the most you can say about him, you probably think Michael Jordan is just a shoe salesman and George Lucas is best known for directing the movie THX 1138.

For as much attention as Eddie’s tapping has always received, it’s one small sail on the mighty ship that is the Van Halen guitar style. And, frankly, you seem to have missed the boat, which I actually envy – because that means there’s an ocean of great Van Halen guitar riffs you have yet to explore.

It’s probably not Van Halen’s tapping that irks you but rather the ’80s-rock cliché that tapping became in the hands of his armies of imitators

Need some pointers? Check out the faux-flamenco of “Little Guitars (Intro),” the Beethoven-level bombast of “Dirty Movies,” the creepy dungeon growls of “Intruder,” the pristine harmonics that open “Women in Love,” the lava-hot blues break on “Ice Cream Man,” the perfect country-rock plucking on “Finish What Ya Started,” the uncommon chords of the Holdsworth-ian “arena jazz” epic “Girl Gone Bad,” the insane thrash of “Sinner’s Swing,” and the soulful cries of the solos on “I’ll Wait,” “So This Is Love?,” “You’re No Good,” and “Don’t Tell Me (What Love Can Do).”

Secondly – not that it matters – but as brilliant as Steve Hackett is, no one knows who first employed the two-hands-on-the-fretboard technique we call tapping. (My favorite pre–Van Halen tapping video is a clip of Italian radiologist and nylon-string virtuoso Vittorio Camardese from 1965.)

What does matter here, though, is that you didn’t factor guitar sound into your assessment of how revolutionary EVH’s tapping was or wasn’t.

Techniques were never Eddie’s focus; the spectacular sounds they yielded were. And I’d be shocked if you don’t agree that the difference between Van Halen’s tapping sound and that of most other tappers is – to borrow a vintage Josh Billings comparison – the difference between lightning and a lightning bug. (For proof, check out “Eruption,” starting at 0:58, or the intro to “Mean Street.”) And, hey, Eddie’s tapping was good enough for two of the greatest music makers of our lifetimes: Quincy Jones and Michael Jackson.

If it’s not good enough for you, consider that it’s probably not Van Halen’s tapping that irks you but rather the ’80s-rock cliché that tapping became in the hands of his armies of imitators. Speaking of that 102-second, kajillion-note 1978 super-solo the world knows as “Eruption,” it does have its critics – most notably Eddie himself.

To him, the piece was just a warm-up routine, and not one he ever wanted to include on a record. Even my friend and longtime mentor, former GP editor-in-chief Michael Molenda, wrote in his EVH tribute for GuardiansofGuitar.com that when he first heard “Eruption” he laughed and found it “over the top and rather silly.”

But, wow, isn’t it interesting that two guitar pals can experience the same song so differently? Flash back to 1982. I was 12 years old and a friend and I had just gotten off the bus out in South San Francisco at the Cow Palace, the 16,000-seat barn where we were excitedly about to see our first rock concert – AC/DC.

As we walked warily past the drunk and rowdy beer-bottle-throwing rock fans already lined up to get into the arena, a lone guitar blasting out of a boombox froze me in my shoes. The tone firing out of those speakers was stunning – hotter than anything I’d ever heard, yet clearer than fireworks at midnight. I was transfixed. It was as if each note had been cut by a laser.

Techniques were never Eddie’s focus; the spectacular sounds they yielded were

“Dude, that’s Angus Young!” I exclaimed, really wanting what I was hearing to be the great lead guitarist we were about see. But even before the solo climaxed with a glorious succession of baroque sounding – and, as I would later learn, tapped – triplet fusillades that very much reminded me of the Bach harpsichord record my mother had recently given me, I had to admit I was hearing someone else. Obviously, it was “Eruption.” And, obviously, I thought it was brilliant.

But if my seventh-grade opinion doesn’t carry enough weight for you, let’s hear what legendary producer Ted Templeman thought of the song when, returning from a coffee break during the tracking of Van Halen’s first album, he stumbled on Eddie warming up on the piece.

“He really didn’t think it was anything,” Templeman writes in his memoir, A Platinum Producer’s Life in Music. “But it was astounding… If I hadn’t walked by at that moment, it wouldn’t have ended up on the album. Now it’s universally recognized as the greatest guitar solo of all time.”

More poignant, though, is the first time Templeman laid eyes and ears on Eddie Van Halen. It was at a near-empty Van Halen gig at the Starwood in West Hollywood.

“I had never been as impressed with a musician as I was with [Eddie] that night,” Templeman writes. “I’d seen Miles Davis, Dave Brubeck, Dizzy Gillespie, all of those transcendent artists, but Ed was one of the best musicians I’d ever seen live. His choice of notes – the way he approached his instrument reminded me of saxophonist Charlie Parker.

“In fact, as I watched, I was thinking there are two musicians in my mind who are the absolute best of the best: Parker, jazz pianist Art Tatum and now here’s the third game changer, Ed Van Halen. So right away I knew I wanted him on Warner Bros.”

From the first Van Halen album onward, game-changing guitar moments came in quick succession – and we’re not just talking about Ed’s famous solos.

As I watched, I was thinking there are two musicians in my mind who are the absolute best of the best: Parker, jazz pianist Art Tatum and now here’s the third game changer, Ed Van Halen.

Ted Templeman

His “’tweener” stuff is sonic treasure as well. For example, as stunning as the solo is on “Push Comes to Shove,” in my mind the way Eddie rides amp feedback in the song’s intro to become a veritable one-man string section is just as incredible.

Similarly, while “Hear About It Later” has a spectacular solo, I also thrill to the soaring, dive-bombing, seemingly improvised melody Eddie throws down beneath the vocals on the final chorus. And then there’s “Beautiful Girls,” a guitar part that, from start to finish, swings so hard, it seems to carry the rest of the band on its musical shoulders, all while firing off fills between the lyrics.

By this point, with my fanboy-level love for EVH on full display, if I add that I saw Van Halen in concert five times and even played in a Van Halen tribute band for a few years, you might conclude that, of all musical genres, high-testosterone arena rock is “my jam.” Far from it. It is actually groove music that has always moved me the most – funk, soul, and so on.

And, to my ears, even though Ed was the quintessential stadium rock guitar hero, the syncopated feel of many of his riffs (such as the verse sections of “Mean Street,” “Somebody Get Me a Doctor,” and “Hot for Teacher”) have more in common with funk music than they do big-hair radio rock.

The only other guitarist who has inspired me as much as EVH over the decades is my first-ever guitar hero, the supremely funky guitarist/super-producer Nile Rodgers. And I was lucky enough to catch up with him just before turning in this EVH remembrance.

“Eddie Van Halen was a ridiculous musician,” Rodgers says, commenting on the great EVH pocket. “Think about this: All the guitar players we love who can really rip are all super-groove-conscious. Look who I’ve played with – Jeff Beck, Steve Vai, John Mayer.

"They all have an incredible sense of groove and funk. If you can shred but you can’t groove, it doesn’t mean anything.” Some signature EVH guitar approaches are easy to learn. For instance, on the “Ain’t Talkin’ ’Bout Love” intro, simple palm muting gives the arpeggiated open-position Am chord a satisfying – and widely copied – spiccato cello sort of sound.

Also, in an era when minor harmonies and power chords were typically the main ingredients in the biggest rock and metal guitar parts, Van Halen proved that simple major shapes could sound just as heavy. Great examples of this are the sizzling-hot major triads that open “Runnin’ With the Devil” and the even more brutal major grips on “Unchained.”

But when it comes to copping the Van Halen vibe, a lot of it is not fully transcribable. Some solos fit cleanly on the staff, but others melt the bar lines and morph time. Some tapped harmonics are basic octaves, while others attack different partials. (Tip: Map out the overtone series on one string to see where the useful nodes are.)

In other words, delivering EVH guitar parts with even a hint of the right mojo is not as easy as memorizing a few notes from a YouTube tutorial. Learning Van Halen is, rather, a lifelong odyssey, and I hope I’ve inspired a few new people to join me on it.

And I salute all the great players I know personally who are already on the eternal quest to play better Van Halen, including Toshi Yanagi, Jennifer Batten, Greg Howe, Doug Rappoport, James Santiago, Paul Gilbert, Russ Parish, Pete Thorn, Caleb Rapoport, Ernesto Homeyer, Jay Gore, Nili Brosh, Terry Lauderdale, Stig Mathisen, Joe Augello, and Matt Blackett, to name a few.

I hope I speak for each of you and every other Eddie Van Halen fan in the world when I say thank you, Ed, for the lifetime of inspiration. No guitarist showed us more clearly that if you have an amazing sound in your head, you can chase it down and bring it to life.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Whether he’s interviewing great guitarists for Guitar Player magazine or on his respected podcast, No Guitar Is Safe – “The guitar show where guitar heroes plug in” – Jude Gold has been a passionate guitar journalist since 2001, when he became a full-time Guitar Player staff editor. In 2012, Jude became lead guitarist for iconic rock band Jefferson Starship, yet still has, in his role as Los Angeles Editor, continued to contribute regularly to all things Guitar Player. Watch Jude play guitar here.

"Why can't we have more Django Reinhardts going, 'F*** everybody. I'll turn up when I feel like turning up'?" Happy birthday to Ritchie Blackmore. The guitar legend looks back on his career in an interview from our December 1996 issue

"Get off the stage!" The time Carlos Santana picked a fight with Kiss bassist Gene Simmons and caused one of the guitar world's strangest feuds