“He said, ‘Count heartbeats and squeeze the trigger. It’s a kung fu trick.’ ” He was the secret weapon behind L.A.'s classic rock legends. Now they reveal the genius behind their favorite slide guitarist

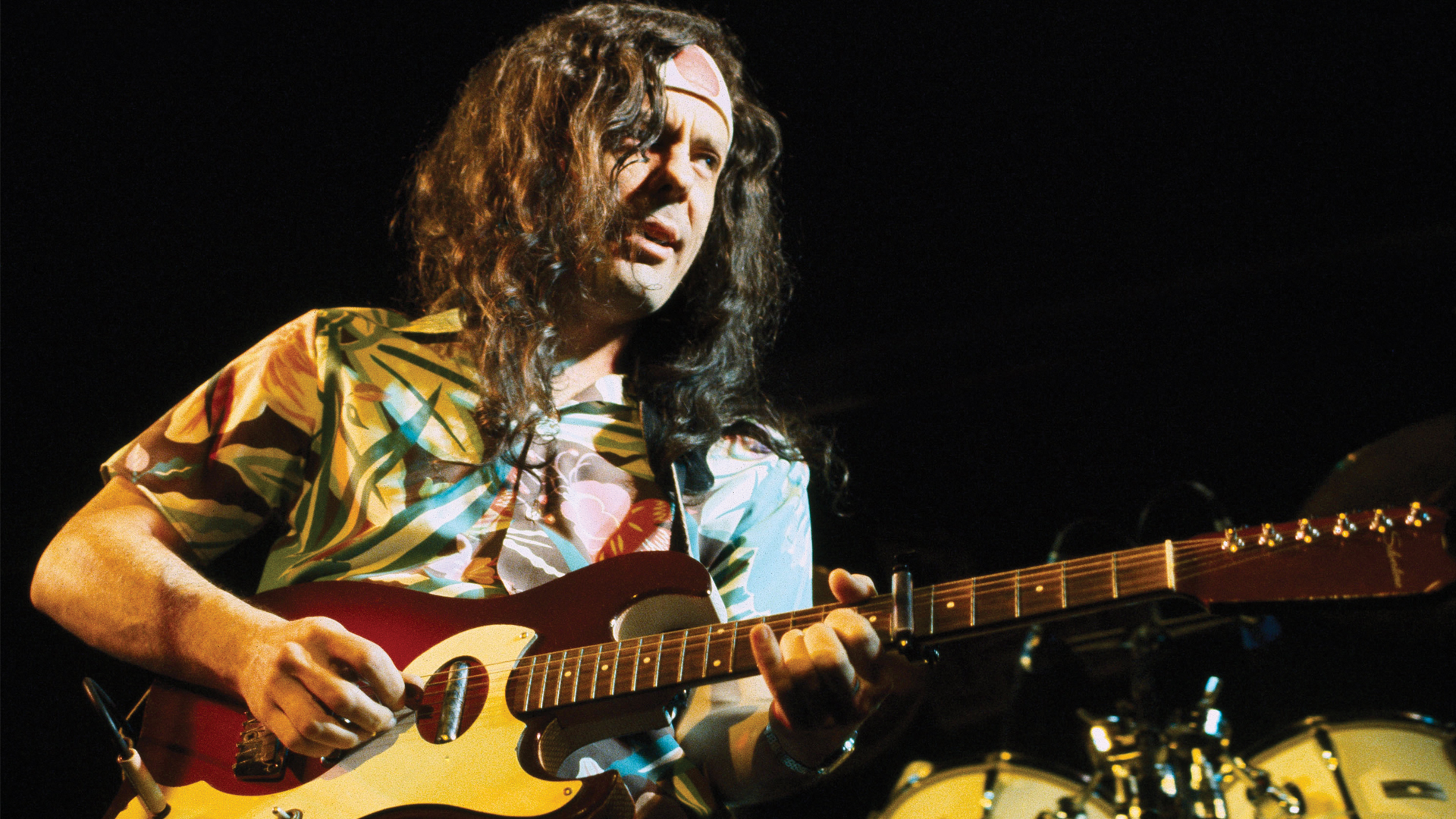

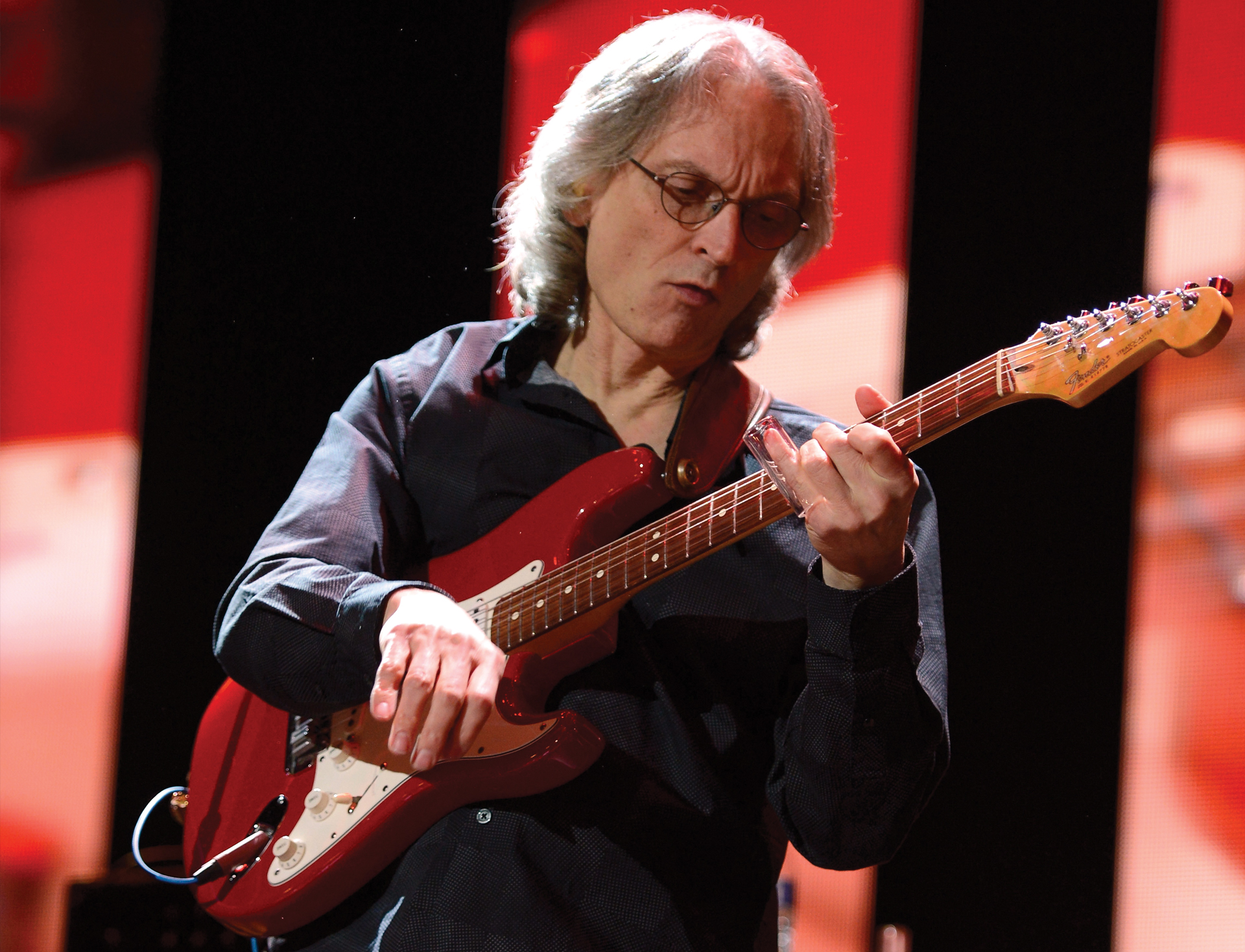

Fluent on guitar and any number of stringed instruments, David Lindley shaped the sound of California's classic-rock era

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

David Lindley was the epitome of a musician’s musician, not only for his comprehensive skills but also for his infectious personality. Lindley was best known as the ultimate sidekick, with crazy credits ranging from Linda Ronstadt, Emmylou Harris and Dolly Parton to John Hiatt, James Taylor and Jackson Browne. His melodic lap steel and signature searing tone totally transformed Browne’s sound in the ’70s, so much that Lindley was practically a second lead voice in his band. “Running on Empty” and “Stay” wouldn’t likely be the classic rock staples they’ve become without Lindley’s presence. (That’s him singing the impossibly high falsetto chorus on the latter track from the Running on Empty album.)

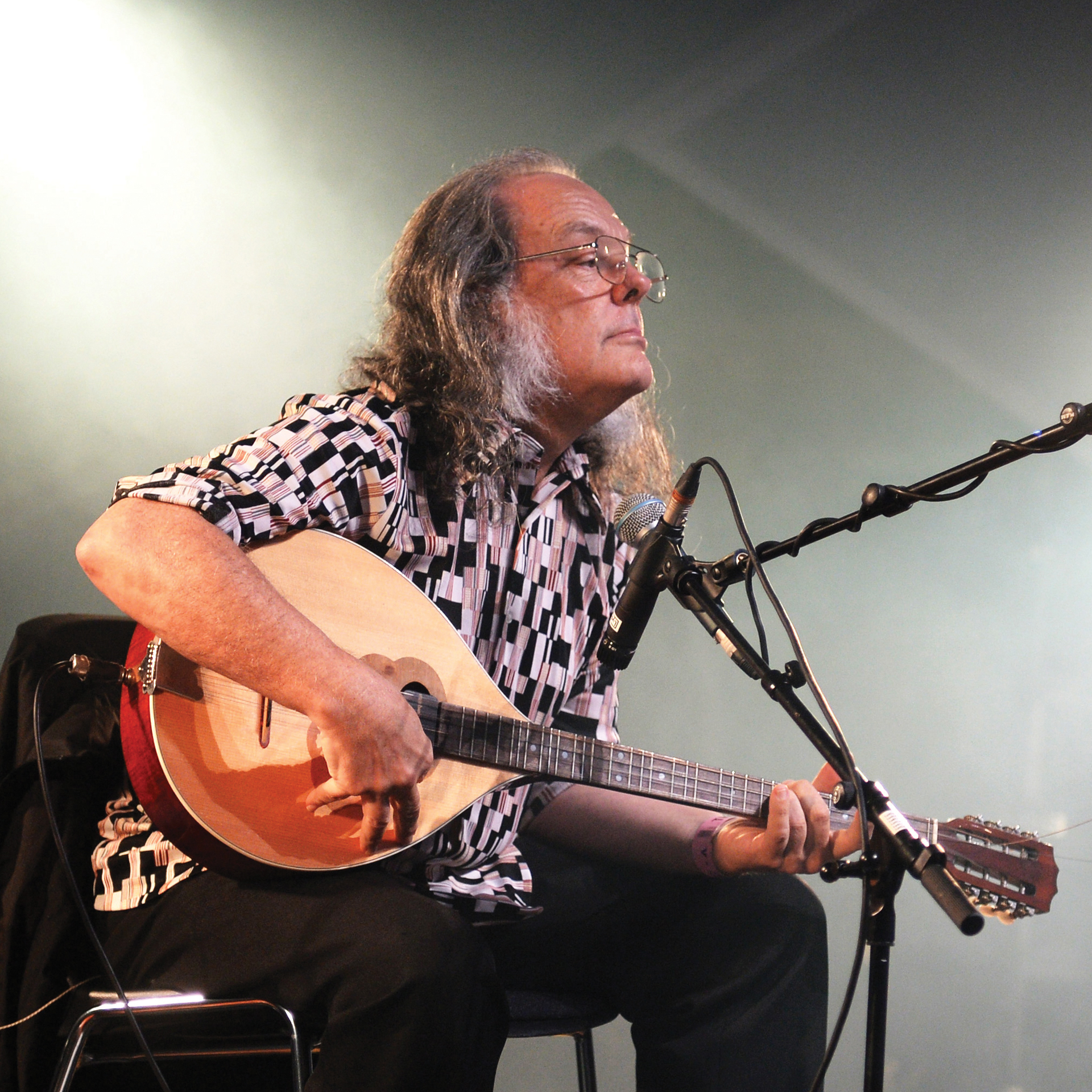

Lindley, who died of complications from Long COVID on March 3, 2023, founded his pioneering world-fusion band El Rayo-X in 1981, and secured Browne to produce their eponymous first album that same year. El Rayo-X received much critical acclaim, respectable commercial success and opened new avenues for Lindley. Along with George Harrison, he brought melodic slide playing to music lovers around the globe, proving its worth beyond the blues.

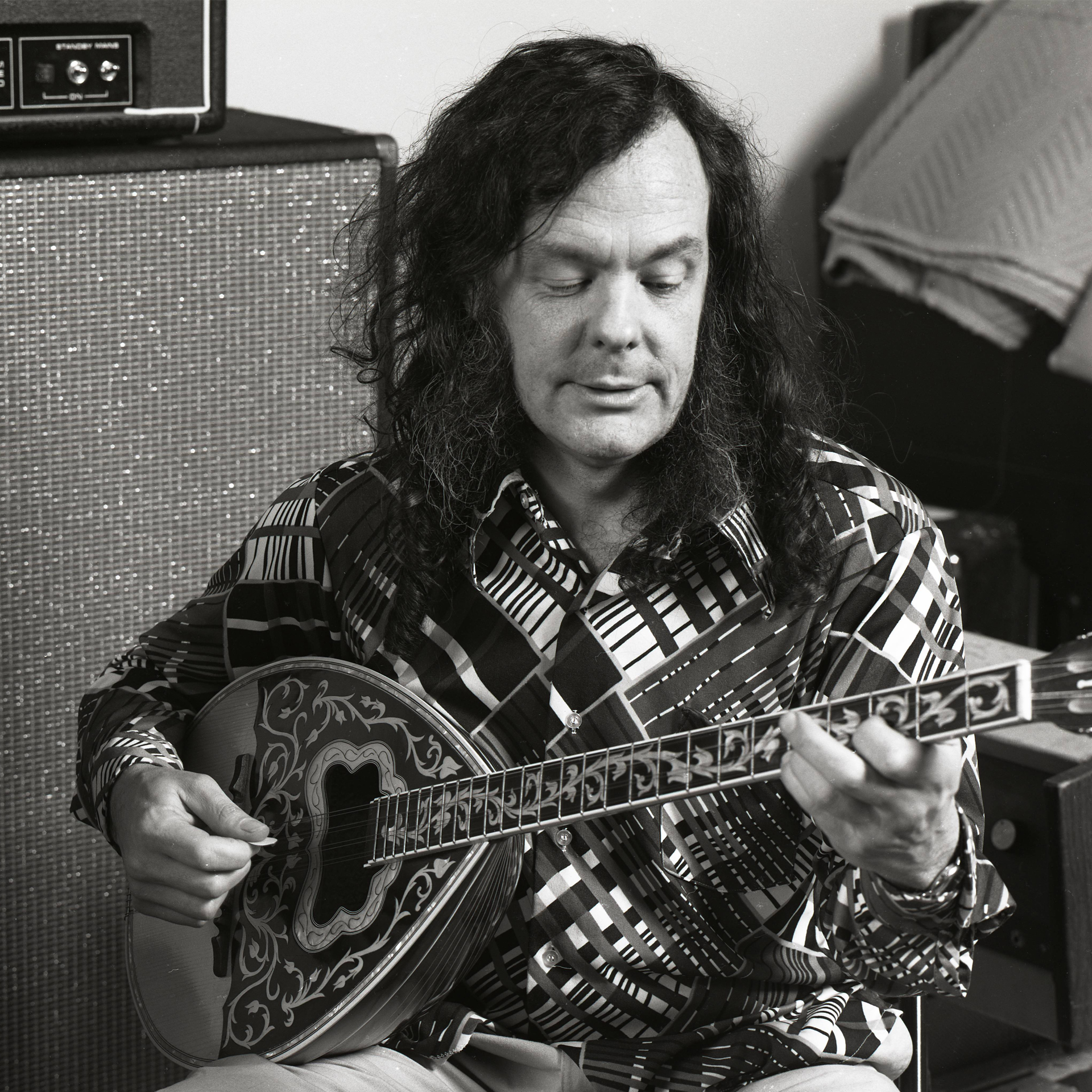

As a musician Lindley embraced playing second fiddle, figuratively and literally. He could play practically anything with strings from anywhere in the world, and he was a master of folk music vernacular. His virtuosity made him the perfect foil for the likes of Ry Cooder, Leo Kottke and Henry Kaiser as well as drummer/percussionist Wally Ingram, with whom he toured and recorded extensively.

Lindley was highly inspirational to some of the planet’s premier players. He lived near the fabled Folk Music Center in Claremont, California, the music store and museum founded by Charles and Dorothy Chase and later run by their daughter, Ellen Harper. Lindley's playing there provoked Ellen's son, Ben Harper, to take up the Weissenborn Hawaiian lap slide. Harper eventually went electric and bought one of Lindley’s coveted Dumble amps. The Overdrive Special he always has onstage might be the exact one that Lindley used on his signature El Rayo-X recording, “Mercury Blues,” considered by many to be the wickedest slide tone ever put to tape. Sonny Landreth had his tonal epiphany after hearing Lindley as well. He and Harper get about as close to the Lindley tone as anyone.

Guitar Player Presents teamed up with Ingram and cosmic blues guru Papa Mali this past May during the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival at the club Chickie Wah Wah to help promote a Lindley tribute that’s become an annual theme at Papa Mali’s Birthday Bash. A parade of Lindley lovers brought his diverse catalog to life. They included Alvin Youngblood Hart, the Wallflowers’ Ben Peeler, the Revivalists’ Ed Williams, Texas blues guitarist Carolyn Wonder-land, Layla Musselwhite, Lindley student Kota Kato, the Iguanas, Jeff Plankenhorn and Marc Stone.

That event, in turn, greased the wheels for this print tribute. I put out a few feelers for comments, and the next day the phone rang from an unlisted number. I answered and a gruff voice said, “Hi, this is Ry Cooder.” The stars had aligned and would eventually bring forward a host of Lindley’s friends — including Jackson Browne, Bonnie Raitt and Sonny Landreth — to share their memories with us.

JACKSON BROWNE

Meeting David Lindley

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“I first heard of David on the day of the Topanga Banjo and Fiddle Contest when I was accompanying the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band [circa 1966–’67]. He was a judge at that point, having won the competition several years in a row. He would win invariably by doing something iconoclastic, such as frailing a bluegrass song on banjo and suddenly adding flamenco rasgueados, which would blow people’s minds.

“David was always eclectic. He just got around on anything with strings. His parents had a vast collection of music from around the world. When he joined Kaleidoscope [the psychedelic group Lindley co-founded in the late 1960s], he was at the nexus of a band that was bending various traditional styles to fit into some other discipline, and at the same time writing its own songs, which lies at the heart of folk music. That was the coin of the realm: casting your own trajectory into an unknown future.”

"I became a better singer, and my timing got better as a player working alongside David’s effortlessly impeccable timing."

— Jackson Browne

Slide Man

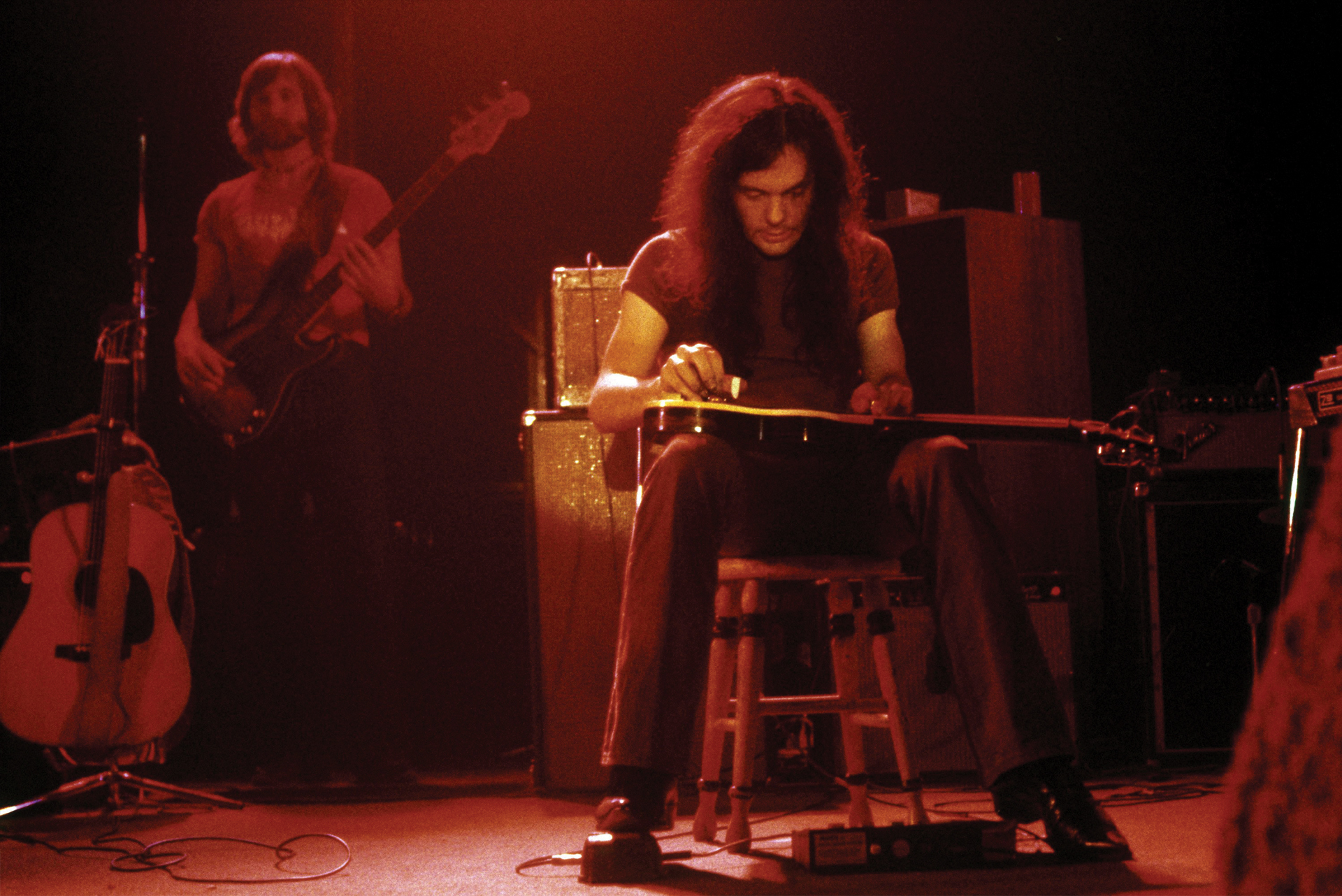

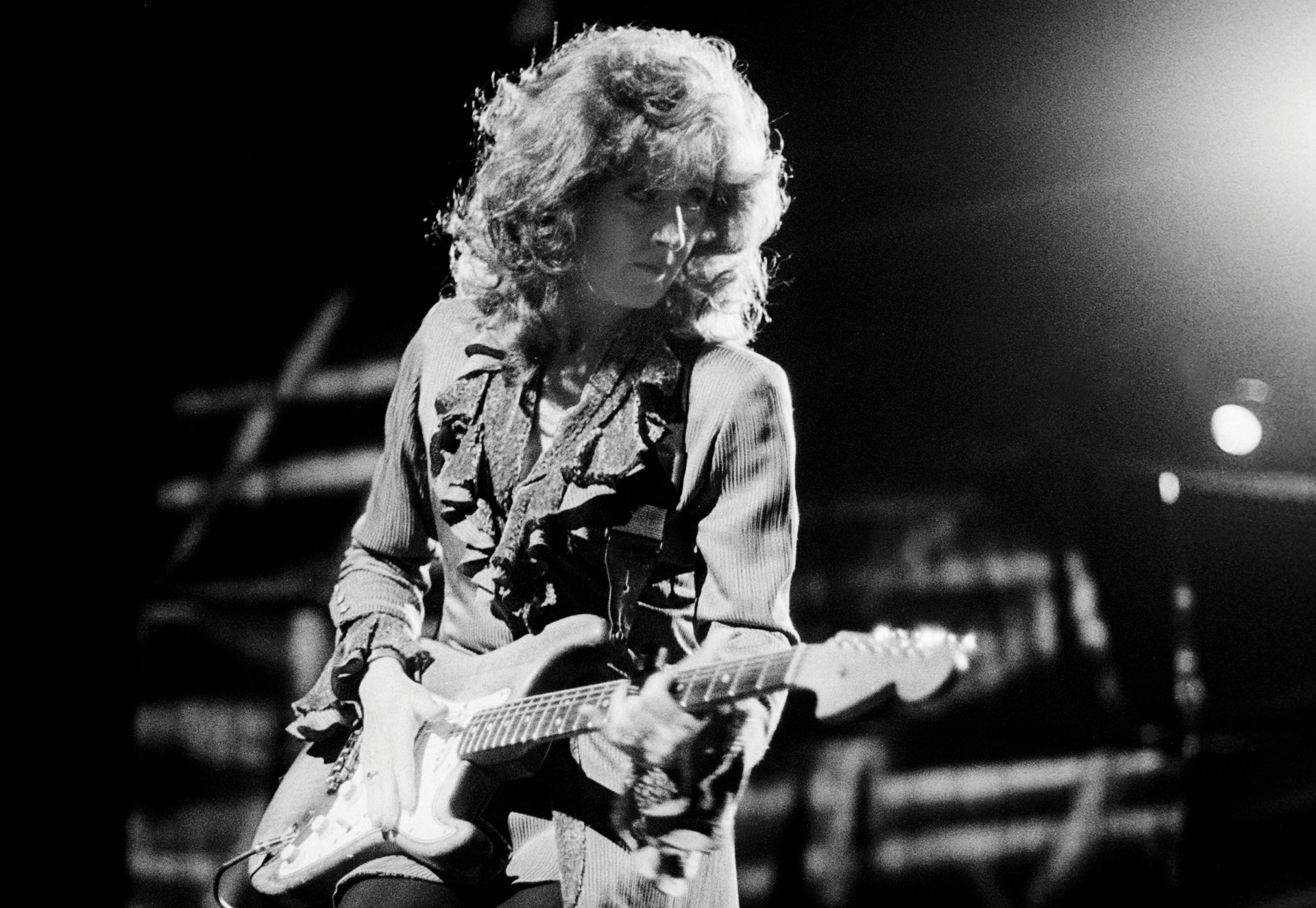

“I first heard David play slide on one of those battleship-grey National electric lap steels in England, when he was on a gig with Terry Reid. He didn’t make it back to the states in time to be featured on my first record [Jackson Browne, a.k.a. Saturate Before Using, 1972]. When it was an unexpected hit, I wound up taking Lindley on the road because it was more manageable, and everything we did together sounded compelling. I became a better singer, and my timing got better as a player working alongside David’s effortlessly impeccable timing.

“David played through a Champ, and it sounded amazing. He got this growl and sustain. He’s a fiddle player, and he wound up making the slide sound very much like a violin. He could do some things that the violin couldn’t, although he could do some show-stopping tricks on the violin too. He was very rhythmic. And playing the violin through the amp, he could use harmonics to make it sound like a Japanese flute. He also traveled with a mandolin. He would play whatever he was inspired to play.

“I really started using his slide work on my second record [For Everyman, 1973]. I’d cut the track with the rhythm section and David would play chord pads on that same National electric lap steel. And then we began the process of overdubbing his solo. [laughs] I wanted it to sound like Ry [Cooder], but David wasn’t playing a bottleneck. We were at Sunset Sound and he was in a vocal booth. I thought it would be a good idea to put a microphone in there with him to capture the sound of the bar on the strings, as the amp was in another room, but all I wound up getting was the sound of David drooling in between phrases. [laughs and makes slurping sounds while heavily inhaling]

“Anyway, we’d left space for the leads when we made the basic tracks. We added David once the vocal and the piano were locked in with an arrangement. A basic tracks session would only take about three hours with studio musicians, and then we’d overdub David multiple times. I would go through and pick the great passages, and he was a part of that process. So it wound up as an accompaniment, like the way it was onstage when it was just me and him. I comped his slide part the way I would comp a vocal, and David would play it enough times to have it well practiced by the end.

“Jim Keltner, who was on drums and an old friend of David’s, had played the ride out on ‘These Days’ imagining a great lead guitar, so he’d played with that dynamic, and David just caught a wave. I think that end solo is put together out of two passes. To me, he defined what that instrument could do, for himself and for a lot of other people, right in that moment. The intro to ‘Redneck Friend’ was another one.”

The Improviser

“Having done that, he could go out and do the same sort of thing live, although he would never play it the same way. He didn’t learn his part and then play it repeatedly; he would only play to the conditions that existed in the moment. He was incapable of committing something to memory and simply playing it back. It just didn’t happen that way for him. He had amazing taste and sense of song, no matter what he did. The conditions had to be right for him to play what he felt, and he always played what he was feeling. I may sing a song with different feelings, but I sing the same notes. I’m not improvising. He was the improviser.”

Hallowed Tones

“David used to play through a Fender Bassman with Vox speakers in the cabinet. When he started playing a Dumble, it accelerated what he was already doing, but I don’t think he’s playing a Dumble on ‘Running on Empty’; he’s playing a Bassman. He was in search of something, and he eventually became the prominent Dumble player of that day.

"Forget about the amp — he would get the sound of the instrument to speak. He would only play what each instrument sounded good doing."

— Jackson Browne

“Lindley’s tone is the whole thing, especially with an acoustic instrument. Forget about the amp — he would get the sound of the instrument to speak. He could sound great going from instrument to instrument, because he would only play what each instrument sounded good doing. It’s easy if you do it that way. Going back to playing that first tour together as a duo, he was like another expressive voice in my songs, and the songs needed that. If you take Lindley away, it’s much less dynamic.”

Evolution

“By the third album [Late for the Sky, 1974] we were working with a band, so it was much more complicated. I got into arrangements during and after The Pretender [1977]. There were things I wanted the music to do that were not a part of our folk conversations or influences. I was a novice arranger, so I’d spend hundreds of takes looking for something, but I wouldn’t know what it was until I found it. One of my favorite things from the later era is his solo on ‘That Girl Could Sing’ [Hold Out, 1980] but by that point our musical relationship had changed. Our friendship was deeper than ever.”

El Rayo-X

“At a certain point David got really into reggae, and he was playing reggae on everything. When he started to do El Rayo-X, I told him, ‘If you’re also playing with me, it’s going to be viewed as a side project.’ In retrospect, I’m not sure that was a good decision on my part, because it meant that then I didn’t have David’s influence and his presence going forward. Although at times I would bring him in and we’d work together, it wasn’t the same as having him in my band. But I think I was right in thinking that if he didn’t say ‘El Rayo-X is who I am and what I’m doing now,’ it wouldn’t have been given as much credence as it deserved. And of course, I produced that first album. I went to my record company saying, ‘You’ve got to record this guy. He’s unbelievable.’

“What he did with El Rayo-X was astounding in terms of the way we viewed David. I’ve been working on making a film about Lindley, and until he passed he was working on it with me. It’s been put on the back burner for a few reasons, but in guitarist Danny Kortchmar’s interview for the film he summed up our feelings: Suddenly this guy that everybody thought of as the ultimate sensitive accompanist became this monster rocking lead guitarist and frontman in a band that presciently harnessed all the interest we had in reggae, which all of us loved but none of us knew how to do.

"I get the credit, but David was always the master of his own journey. He always did what he wanted to do."

— Jackson Browne

“I sang on El Rayo-X and worked on some technical stuff with my engineer Greg Ladanyi. But all l really did was preside over the sessions. You need somebody on the other side of the glass. I get the credit, but David was always the master of his own journey. He always did what he wanted to do. He was never a prisoner of someone else’s idea. He always made it his own. And when he made El Rayo-X, he truly came into his own. He was the leader of that band. He chose every song and every player. But I am so proud of the record and having been there.”

The Everyman for Everyone

“David was a unique player who affected and influenced so many people, and he participated in so many people’s music. For Lindley to go play with Ry, a master of so many idioms, was the perfect join-up. So was the stuff David did with Henry Kaiser, traveling all over the world as a master American musician to connect in musical conversations with others from all these different cultures. What I’m hoping to eventually do with the film is shine a light on this: Lindley’s kind of an everyman in that he was not famous, but everyone wanted to play with him. It’s like being let in through a side door to see how this guy was so respected and so valued, why he was so valued, and how that kind of musical life is available to anybody who wants to try to find it.”

RY COODER

Seriously Funny

“I always enjoyed David as a person because he seemed so warm-hearted. He was very kind. People demonstrate their personal quality in their music. Sometimes you meet somebody with a like-mindedness, and that’s why we used to play well together.

“Aside from being a very humorous fellow, David had great dedication as an improviser. So on one hand he’d clown around and wear funny shirts, but he was also very serious. I appreciate that. Music, especially folk music, is like tools. You master these tools so that you can polish these folk styles into something useful to do. That’s what David did. He had the fiddle, banjo and guitar, so he could fit into any situation and add his color.”

“To get that kind of control when he played, he went into this kind of trance. Not like out of his mind, more of a discipline that allowed him to make a good sound.”

—Ry Cooder

Kung Fu Tricks

“David had great hands with perfect control. That’s quite a combination, to have the fluency and the control down tight. He had physical training from doing kung fu and shooting guns. I once asked him, ‘How do you always beat the guys at target practice on the shooting range?’ He said, ‘Count heartbeats and squeeze the trigger. It’s a kung fu trick.’ He was a very inventive, very eclectic guy. To get that kind of control when he played, he went into this kind of trance. Not like out of his mind, more of a discipline that allowed him to make a good sound.”

One Slide Ace to Another

“As a slide player, you must have control and be able to hit notes. It’s a bowing thing. You’re moving the slide, vibrating it however you do, and it sounds weird if you don’t hit the notes. David’s good ear could hear the good note, find the center of it and play the goddamn thing. It’s very effective when you do that and shape it like a violinist. He had great technique playing with the guitar lying flat, rather than as I do, playing bottleneck in the regular guitar posture. That tends to put you down different roads. He would play one way, and I would play the other way, just by nature. So it was very complementary.”

Southern California Reggae

“Then there was the fantastic rhythm when he played using his first finger as a pick. You get a certain snap on the strings that way. We’d play this folky reggae thing that he used to like to do. It had this fabulous quality. I would only do it with him. Nobody else could cop that groove like he could. It was his groove: Southern California reggae. And he liked to play double-stringed instruments, like the oud, and he had a 12-string guitar with lipstick pickups and those LaBella black, tape flatwound strings. It was teardrop shaped and was sort of colored like bacon fat. Man, he would make that killer axe walk and talk. When he’d hit that reggae rhythm on that guitar, it felt so good. It was like lift-off. You could play anything and have a ball. It would make you jump — make you want to rock.

“It was always encouraging to play with him, and you never worried, because you knew it was going to be all right. So often you run into taste issues and hit the wall, but not with him. We just seemed to hit it off and have a good time. It was always okay, especially onstage.”

War Story

“We used to play these mud festivals in Europe — oh my god. I remember one where a guy picked us up at the airport in a Volkswagen, naturally, that didn’t have enough room for our stuff, so we had to stick it up through the roof and out the window. [laughs] When we got to within five miles of the site, the car started to shake. I said, ‘What’s going on?’ ‘Oh, that’s Lenny Kravitz.’ ‘What?’ The bass is shaking the car from five miles away, and we have to follow that? ‘Well,’ David said. ‘Let’s just walk through the farmer’s muddy pig field and do it.’ The stage was so big that the people couldn’t see us. If they could, they figured we were roadies testing and tuning up for the main act. We would do our 45 minutes, get our good money, and get back in the Volkswagen.

“David never batted an eye. He had real stamina. That all used to drive me crazy, but not him. He was a good road hog. I would complain my head off, but he would soldier on with no complaints. Touring is a nightmare, but he made it enjoyable, being very funny and light-hearted. It was never life-threatening with him.”

"Touring is a nightmare, but he made it enjoyable, being very funny and light-hearted. It was never life-threatening with him.”

— Ry Cooder

El Rayo-X

“I gave him that name: El Rayo-X. We would come up with shit like that casually in conversation. He asked what he should call his group, I suggested calling it that, and he did. I just thought it was a cool name, but it turned out to be the name of a Panamanian prize fighter. Lindley found out later. I suppose I’d seen it in print. ‘David Lindley and the El Rayo-X’ is a little exotic, but it’s funny. It fit him. He was a cheerful character. And that was another thing, the character he devised for himself: the guy with the polyester shirts. [laughs]

“David had such a terrible time later. He damaged his ears. You know, cymbals in your face, and amps that are capable of rearranging your molecular structure. It’s too bad he suffered because of that, and I’m very sorry. But we had so much fun.”

SONNY LANDRETH

On Mentorship

“Looking back on the past 40-plus years, I can’t imagine the ride without David Lindley at the wheel, showing me the way when I needed it. By 1974, I was mostly playing acoustic and had techniques and concepts of my own, but I didn’t have a clue about tone and developing my own sound on the electric. Then, snowed in during a winter in Estes Park, Colorado, I discovered David on Jackson Browne’s great albums For Everyman and most especially Late for the Sky. That just knocked me out. He had such a powerful sound, yet his phrasing was so nuanced and lyrical that it echoed the poetic sensibilities of Jackson’s profound songs. That combination of songwriting art and tasteful, whup-ass guitar had a big impact on me. I felt like I’d been pointed in the direction I was meant to take.

“Five years later I got to hear them together on the Running on Empty tour at the Jackson, Mississippi, Coliseum, and then I heard David with El Rayo-X at a small club in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1988. Of course, he sounded amazing, and that fired me up. Of all my slide guitar heroes, Ry Cooder and David Lindley have touched me the most. David became a mentor with conversations that were equal parts information, advice and comedic relief.”

The Breakfast Club

“We met over breakfast at the Winnipeg Folk Festival hotel in 1988 and would connect off and on over the years via phone or find each other at workshops and gigs we played together. He had a 50-watt Dumble, so I was all about getting one. But he discouraged me. He said, ‘No, man, they’re too complicated and too expensive.’ His other guitar player at the time, Ray Woodbury, had a Demeter, and David said, ‘You want this amp.’ So I called Jim Demeter and we became fast friends. I got one of his amps and I’ve used one or more of the three I own on at least 80 percent of everything I’ve done in the studio since.”

“The beautiful thing about David was how he shared his gift and sense of humor both onstage and off. I recall a press conference at the Singer-Songwriter Festival in Frutigen, Switzerland, becoming a bit dull and quite awkward, but Lindley, the bringer of fun, lit the whole affair up as soon as he walked in. He and Wally Ingram, running late due to hard traveling, arrived just in time for Mr. Dave to save the day. Wally joined Steve Earle and me at a table facing the group of reporters and journalists who were now all abuzz. David patiently answered their questions about the music biz, working with big-name artists, songs and gear, until it was time to wrap it up. I jokingly said, ‘I have a question. Brother, where do you shop for clothes?’ Though laughter broke out in the tent, David was unfazed and without hesitation began to seriously name his favorite stores in California. Some of the journalists were actually writing the information down. I’ve always wondered if his list sparked a few overseas shopping missions for polyester suits.”

BONNIE RAITT

Meeting David

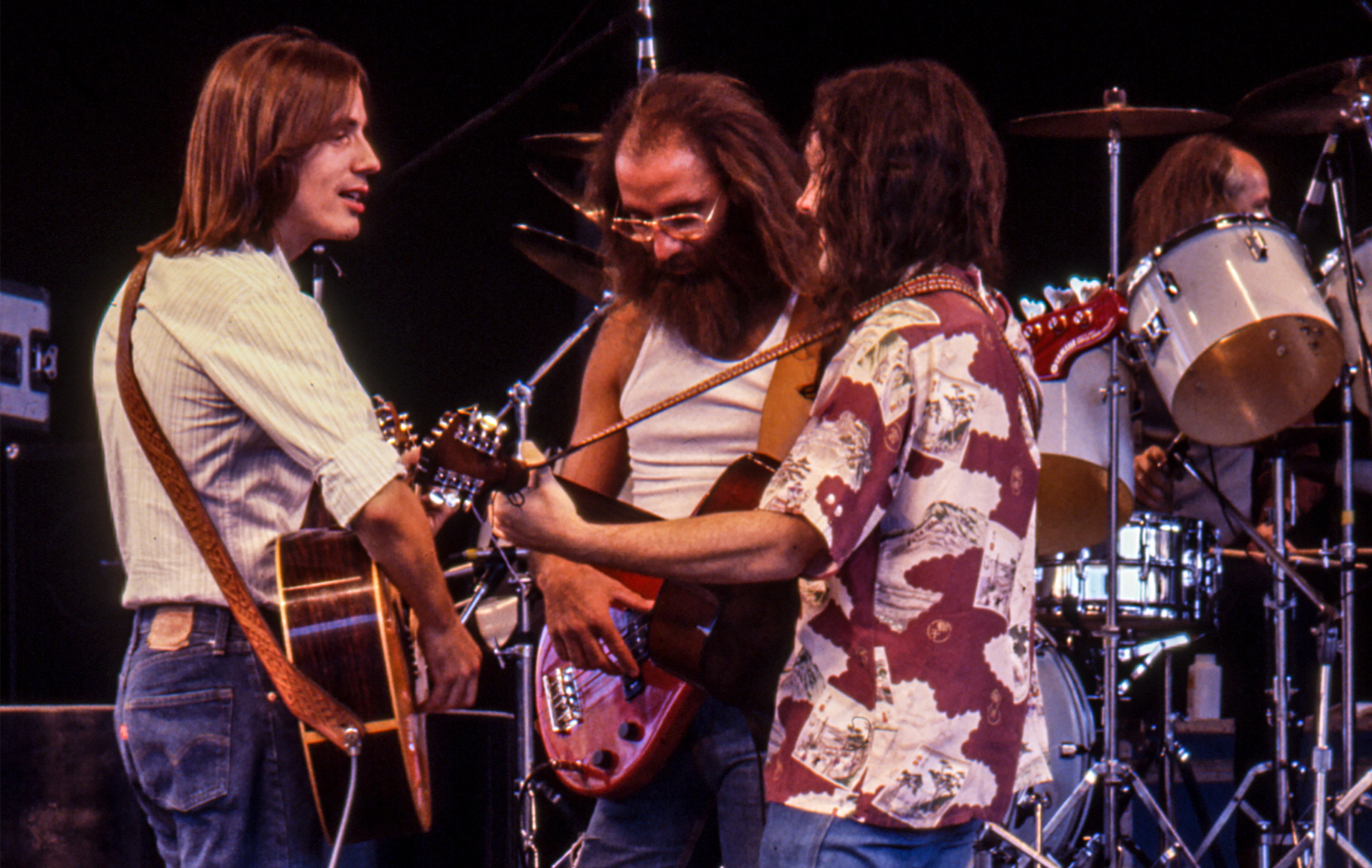

“I became friends with Jackson Browne in 1970 or ’71 when I first opened for him, and then at some point I met David when he started playing with Jackson. I was very excited to open Jackson’s national tour in 1974, which was my first national tour, and our two bands were on one bus. So it was one woman and 13 guys, of which David was my favorite. It was such a blast. We developed a close friendship that would last a lifetime.”

Taste and Tone

“David’s reputation preceded him in musician circles, so I was familiar with his virtuosity on the fiddle and his sensitivity in terms of playing perfectly on Jackson’s tunes. I can’t even imagine most of Jackson’s songs that David’s on without his contributions. Playing lap steel was just one of the great things he did. His taste, tone and approach to augmenting whatever the singer and the song needed was perfect. He set the standard for me of what great accompaniment could be, long before he went off on his own and had one of my favorite bands of all time, El Rayo-X. Thinking back to when I first met him, his virtuosity was astonishing, but he didn’t lead with it. He did it quietly. He was delightful and a perfect foil for Jackson. His personality came across in his playing and his stage presence, no matter what his role.

“I was knocked out at his lap-steel playing. It’s a completely different instrument, but it can do so much similarly to slide guitar, especially when you’re looking at Ry Cooder and Lowell George and David. They set the tone for me on how slide guitar can fit within a song that’s not just in a blues idiom.

“David’s tone is the perfect blend of grit and richness, but I didn’t really go to him for that. It was more about his taste and his lyricism. His choices about what licks he put where, how he played them and which octave — all of that was a great influence on me.”

In It for the Music

“Because we were both touring non-stop in different bands, we didn’t interface very often. When we would interact over subsequent decades, he knew how much I loved his sense of humor, and he was extremely witty and sardonic. I also loved the fact that he just couldn’t care less about the record business. He was like Ry Cooder in that they would deliberately avoid trying to be commercial in any sense. I was simpatico with that. We were there for the music, not for the hit record. So you win your stripes and your friendship by the respect you have for each other, and we shared great love and affection as friends.”

The Sensitive Ones

“We eventually toured together again, along with Jackson, Bruce Hornsby and Sean Colvin. I believe it was in ’98. We joined forces for almost two months across the country outdoors in a kind of a supergroup, which we lovingly referred to as the Sensitive Ones, because people would always make comments about Jackson’s music being so sensitive. David and Wally opened the shows, and then we would all do four or five solo songs, each of us backing the other ones up. “That tour is one of the high points of my 54 years on the road, partly because I got to hear David and Wally slay the audience every night, just the two of them.

“We had one memorable time when we all went through his legendary polyester wardrobe, showed up and surprised him. I don’t think we did the gig in that — my memory of it is hazy — but I loved his satirical splendor and his quirkiness. He was a fantastic artist as well. His drawings were incredible.”

One of a Kind

“Nobody delighted all of us as much as David. To be that much of a genius as a multi-instrumentalist singer/songwriter and a performer, and then have that incredibly engaging personality — I’ve never met anybody like him. And I have to say that El Rayo-X is one of the greatest configurations of musicians and material and groove. I mean, the guy had a groove that was just unbeatable. He was literally one of the funkiest human beings I’ve ever heard in my life. Nobody tells funnier stories onstage. And his voice — [laughs] — I’m so happy to be able to talk about it because it makes him feel alive for me again. Thank you very much for honoring his memory. David is beloved by so many fans and musicians and will always be. I’m so glad that Guitar Player is doing this tribute. I’m happy to celebrate my pal.”

Jimmy Leslie is the former editor of Gig magazine and has more than 20 years of experience writing stories and coordinating GP Presents events for Guitar Player including the past decade acting as Frets acoustic editor. He’s worked with myriad guitar greats spanning generations and styles including Carlos Santana, Jack White, Samantha Fish, Leo Kottke, Tommy Emmanuel, Kaki King and Julian Lage. Jimmy has a side hustle serving as soundtrack sensei at the cruising lifestyle publication Latitudes and Attitudes. See Leslie’s many Guitar Player- and Frets-related videos on his YouTube channel, dig his Allman Brothers tribute at allmondbrothers.com, and check out his acoustic/electric modern classic rock artistry at at spirithustler.com. Visit the hub of his many adventures at jimmyleslie.com