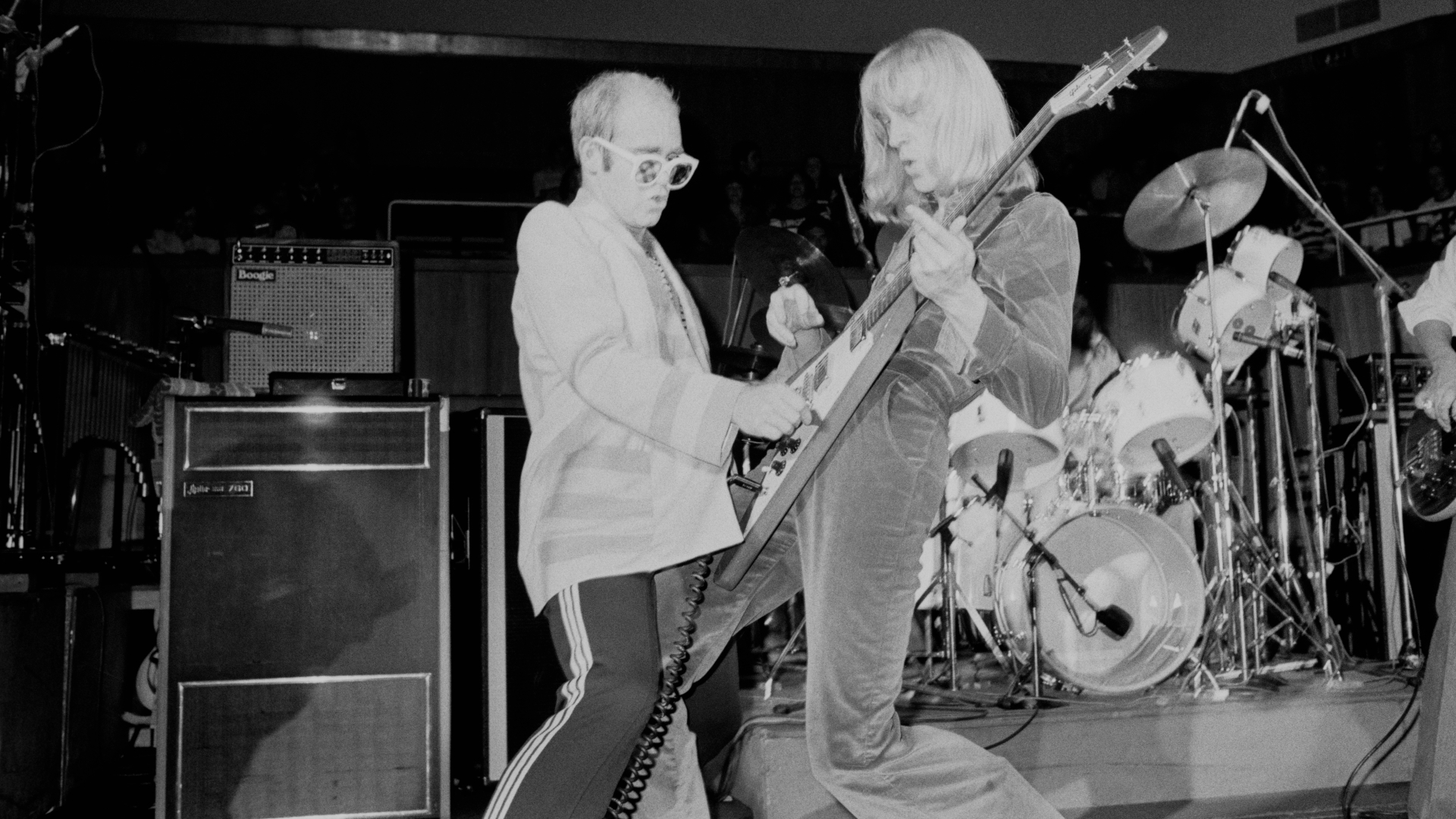

“I said, ‘Okay, why don’t you flip the tape over?’ I wanted to try a backward guitar solo.” Davey Johnstone explains his greatest guitar moments from Elton John’s ‘Goodbye Yellow Brick Road’

How much time does it take to make a classic album? If you were part of Elton John’s band during his early 1970s heyday, not much at all.

As guitarist Davey Johnstone explains to Guitar Player, many of John’s early, best-selling records were cut in just days.

“We worked very quickly,” Johnstone says. “That’s how things were done in those days, and we didn’t think anything of it. We did ‘Rocket Man’ [from Honky Chateau] in three takes, and [Goodbye Yellow Brick Road’s] ‘Saturday Night’s Alright for Fighting’ only took two passes to get it right. I know that probably sounds astonishing to a lot of people, but the truth is, we knew what we were doing. The creativity just flowed. We were recording and touring all the time, but we were having the time of our lives. It really was such a brilliant era for making music.”

Elton’s 1973 double-album Goodbye Yellow Brick Road is a prime example. The double-album — which was released on October 5 of that year — took all of 16 days to make. Its 17 tracks include such classics as “Candle in the Wind,” “Bennie and the Jets,” “Saturday Night’s Alright for Fighting” and — one of the tracks with which Johnstone is most associated — the opening cut, “Funeral for a Friend/Love Lies Bleeding.’

“It’s been a staple in our set for a long time," Johnstone says of the track. "Of course, the song starts with that symphonic synthesizer section that David Hentschel did such a brilliant job on. [Hentschel, the album’s engineer, wrote the intro using elements of various songs on the album and performed it on an ARP synthesizer.]

“Then we come in with the slow part, and it’s just Elton on acoustic piano and me doing volume pedal slides that sound kind of like Indian flutes or something. From there, we continued straight on because we wanted ‘Love Lies Bleeding’ to come in after ‘Funeral for a Friend’ seamlessly.

“I did a bass guitar part during the whole of ‘Love Lies Bleeding’ on my Les Paul. It was a three-pickup Custom that Elton had bought at Manny’s Music in 1972. I picked it out for him because he wanted a guitar. However, I unfortunately had some guitars stolen, so he said, ‘Use this one for a while.’ I ended up playing that guitar a lot, and it’s on this song.

“I worked out a very specific guitar riff because Elton wanted a recurring part that was kind of ringing and chimey. It became sort of a theme of the song. There’s also those big power chords that I play.

“A lot of people have said to me, ‘That’s so iconic,’ which is always nice to hear. People have grown up hearing these parts. There’s a lot of rhythm guitar throughout — that’s the Les Paul going through a couple of 50-watt Marshall tube amps.

“For the solo section, I went back to the goldtop. I can’t tell you how much fun it was to play a part like that. Elton was a huge guitar fan, but he’d never been in a band like ours, so he was loving it. He would always say, ‘Do another guitar. Double-track that!’

A key aspect of Johnstone’s job — and one that he relished — was coming up with guitar riffs. In addition to “Love Lies Bleeding,” he points to songs such a “Saturday Night’s Alright for Fighting” and “The Bitch Is Back” as key examples.

“Those are definitely mine,” he says. “We’d be running down a song, and somebody would say, ‘We need a great guitar thing for the beginning, and after the chorus we’ll come back to it.”

He singles out “Candle in the Wind,” however, as a rare — and memorable — instance in which John himself had a firm idea for what he wanted to hear.

“Elton came up with a great guitar riff, but to be honest, I didn’t think it was going to work,” he says. “His idea was that every time he would sing the words ‘candle in the wind,’ I would play the guitar lick underneath. I didn’t think that would sound right; in fact, it went against my grain of playing a guitar lick over such an important line.

“But Elton was very keen on it: ‘David, I really want you to try that.’ I said I would give it a shot. The part came up, I did the overdub, and sure enough, I thought, Oh, actually, that sounds pretty good. We kept it in and I doubled it.” He laughs. “I have to admit, to this day, it sounds pretty good.”

Most of the time, though, Johnstone was the architect behind his riffs and his tone. One of his greatest signature moments on Goodby Yellow Brick Road is his snarling guitar work on the track “All the Young Girls Love Alice.”

“It opens with that really cool guitar volume swell. That’s through a Uni-Vibe, which I’ve used for various sounds since way back,” Johnstone explains. “In those days there was very little hardware available for guitarists. You maybe had a volume pedal, a Cry Baby wah pedal, a fuzz pedal and a Uni-Vibe.

“That was kind of it. But I loved the Uni-Vibe. When you put it to the upright position, you would get this beautifully slow phasing sound. Conversely, when you flattened it out, it would create this fast wobbly sound, almost like a guitar through a Leslie cabinet.

“I found out that if I used the Uni-Vibe in conjunction with my volume pedal, I got this wonderful singing sound as it got louder.

“Then I went into the guitar riff. It needed something kind of harsh and aggressive. Elton loved that one. It’s another part that I came up with and he went, ‘Oh, shit, that’s great.’ It’s a very pumping song, so I pretty much jumped on what Elton was playing on the piano. I clicked off the Uni-Vibe and we just went to a straight crunch sound for the basic structure of the song.

“Then at the end, I did all kinds of overdubs, using, believe it or not, a bottle on my guitar strings. That’s how I got all those phasing sounds. They sound like cars going by, which we did overdub as well, but a lot of them are guitar effects that I did.”

Considering how few effects pedals were available at the time, it’s not surprising that Johnstone and producer Gus Dudgeon sometimes relied on studio tricks to achieve their desired sound. A perfect example is Johnstone’s backward guitar solo on the first disc’s closing cut, “I’ve Seen That Movie Too.”

“It’s such an atmospheric song,” Johnstone says. “For the bulk of the track, it was mostly acoustic rhythm guitar because I thought that gave it that nice darkness. Paul Buckmaster began writing this great string arrangement, and I didn’t want to get in the way with too many electric guitars.

“However, Gus said, ‘Look, I really feel that this should have a guitar solo.’ So I said, ‘Okay, why don’t you flip the tape over?’ I wanted to try a backward guitar solo. It wasn’t so easy. You literally had to turn the tape over on the spools, rewind it and rewrite the track sheet so that we’d know which track the guitar was going to come up on. And you never knew what you were going to come up with when you played it back.

“Getting a backward guitar part is really hit or miss, but I’ve always loved the effect of it after I first heard the Beatles create it on songs like ‘I’m Only Sleeping.’

“Gus got the tape all ready and marked it up where the beginning and end would be. My plan was to make half of the solo backward so it would be all cool and different, and at the end I’d bring in some straight-ahead electric stuff. I thought that would really tear people’s hearts out. That’s the way we did it, and it came out great. Obviously, there was some luck involved.

“When we all heard it back in the control room, everybody was screaming, ‘Holy shit! That’s it!’ It was exactly what I wanted, and it sounded beautiful. There were a lot of good, happy accidents like that. Sometimes we tried things that didn’t work out so well, but we had the luxury of experimenting. We were very fortunate to be able to do whatever we wanted on those recordings.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

“We’d heard Jimi Hendrix, we'd heard the Who, but now we finally got to see these guys. And watching Jimi Hendrix burn his guitar….” Grace Slick on Hendrix at Monterey, Jefferson Airplane and the Spanish origins of “White Rabbit”

“I’m still playing but I’m covered in blood. Billy’s looking at me like, ‘Yeah! That’s punk rock!'” Steve Stevens on his all-time worst gig with Billy Idol — and the visit to Jimi Hendrix's grave that never happened