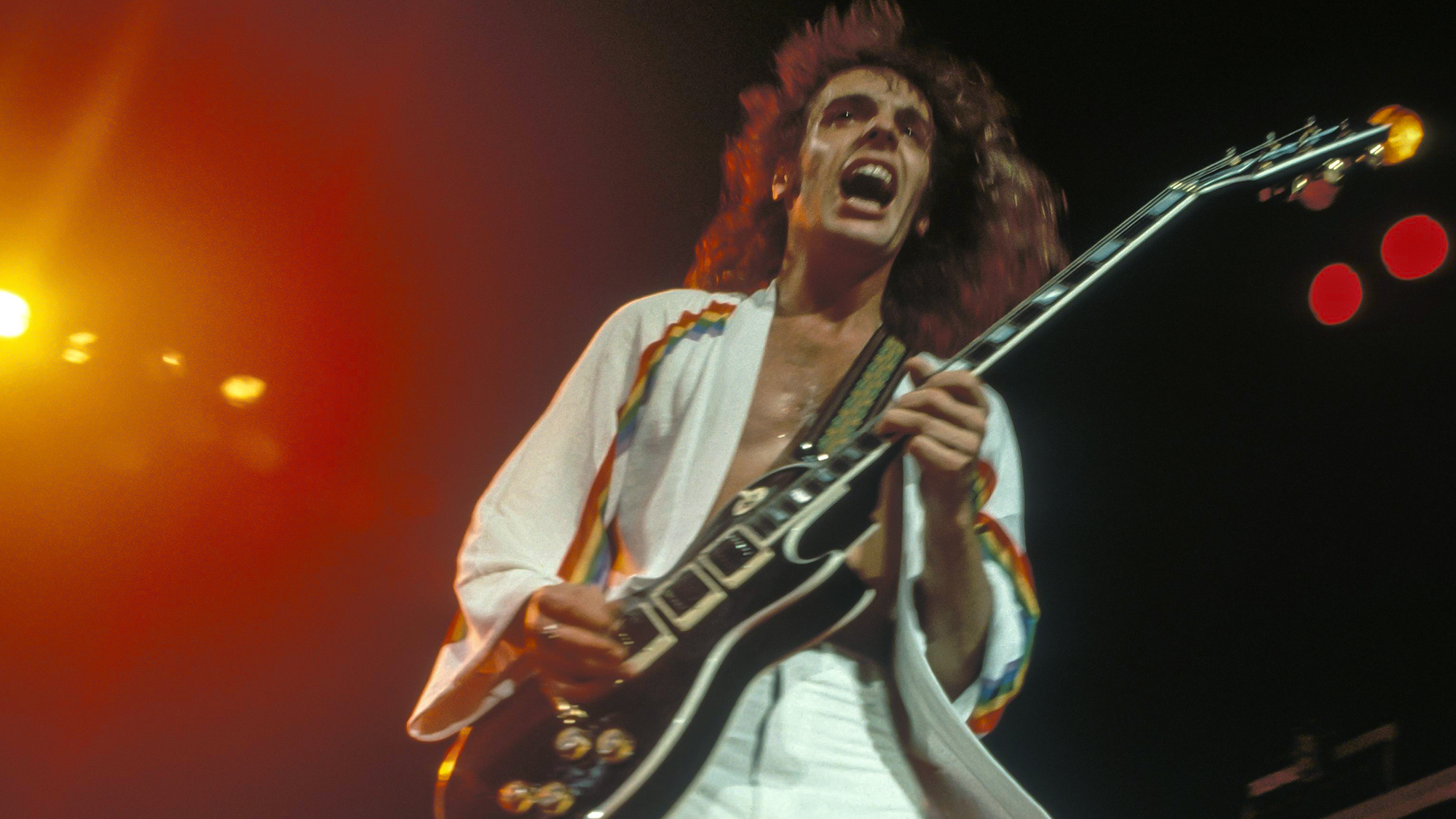

“This guy gets up and starts playing — and I'm like, Who the **** is this!?” Dave Mason on meeting Jimi Hendrix in 1966 and making “All Along the Watchtower” with him

Dave Mason has been one of the great collaborators in rock and roll history, consistently in the room for some of music’s most memorable moments. He was an original member of Traffic, writing the band’s first two great hits, “You Can All Join In” and “Feelin’ Alright?” He quit the group as they took off and rejoined soon after, only to be abruptly fired by Steve Winwood and company.

Along the way, Mason played on Jimi Hendrix’s cover of Bob Dylan’s “All Along the Watchtower,” Paul McCartney and Wings’ first number one hit — “Listen to What the Man Said” — and the Rolling Stones’ “Street Fighting Man.” In 1969 and 1970, he was a member of Delaney & Bonnie and Friends on a tour that briefly featured guest appearances by Eric Clapton and Harrison. That connection would prove fruitful when Mason performed on Harrison’s All Things Must Pass solo effort and formed the original lineup of Derek & the Dominoes with Clapton.

Mason’s first solo album, 1970’s Alone Together, was a classic that included the song “Only You Know and I Know,” which became a staple for Delaney and Bonnie, and in 1977 he had his biggest solo hit with “We Just Disagree.” He has been touring extensively for decades.

Of all Mason’s musical exploits, it's his work with Hendrix on “All Along the Watchtower” that draws the most attention. Mason — who met Hendrix shortly after the guitarist's manager, Chas Chandler, brought him to London in September 1966 — joined him on the initial recording session for the track, on January 21, 1968, at London’s Olympic Studio.

Mason recounts the experience and his many other musical highlights in his new memoir, Only You Know & I Know, co-authored with Chris Epting. GuitarPlayer.com caught up on him on the phone from California, where the British guitarist has mostly lived since 1971. Shortly after we spoke, Mason announced he was rescheduling his fall tour dates to attend to a medical matter, but said he plans to reschedule and tour again starting in early 2025 after he recuperates.

In your self-perception which comes first: singer/songwriter or guitarist?

I consider myself a guitarist first for sure. That's what I wanted to do when I started out and I was listening to the Shadows and the Ventures and Chet Atkins.

You quit Traffic just as the band began to take off — scared, you said, of success. You rejoined and were settling back in when you were abruptly fired by the other members. Why did you start your book with the scene of being fired from Traffic? It seems to have been a very painful moment that caught you completely flat footed.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

That was the suggestion of Chris, and I thought it made sense once I took a second to contemplate. We have that opening, and then I have a reveal at the end that I guess I shouldn’t give away… But if I had a dollar for everybody who’s asked me “Why don’t you guys get back together?,” I’d be very wealthy. But you’re all asking the wrong guy, and I lay that out.

Do you consider yourself a difficult character to get along with? What happened there?

No. In the beginning, I was writing the hits — “You Can All Join In” and “Feelin’ Alright?” — and frankly I think there was a lot of jealousy there.

You ended up collaborating with so many of music’s icons. In addition to Steve Winwood there's Jimi Hendrix, Steve Winwood, Joe Cocker, Delaney Bramlett, George Harrison and Eric Clapton. Did you come out of each experience feeling like you had learned something?

Yes. I didn’t do this consciously but if you're going to learn something, you may as well try and put yourself around the best. That’s how it worked out for me. It’s not like I made a bee line for this or that person, but it just happened out of the situations that I was in.

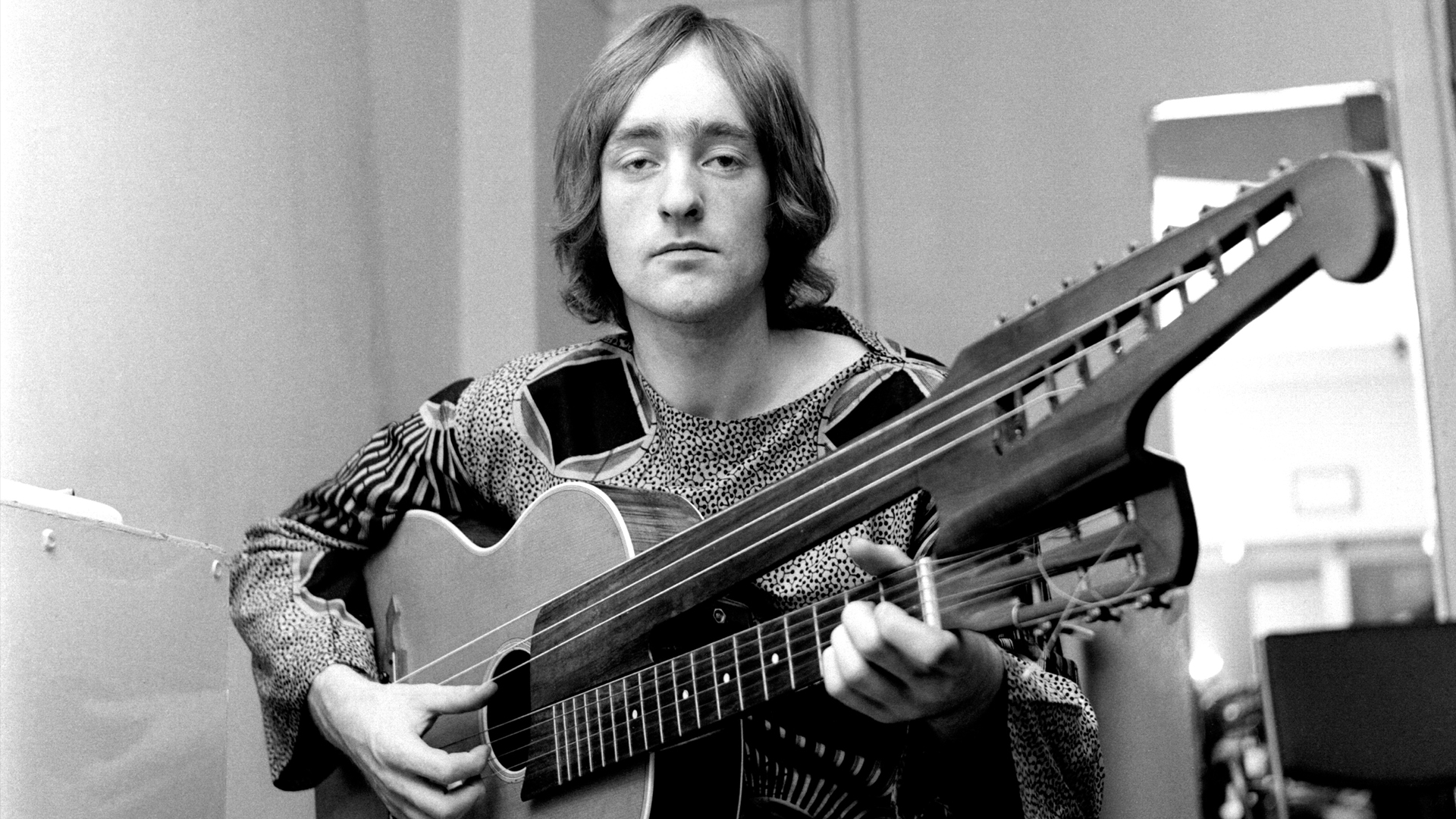

Let’s talk about some of those specific experiences. What do you remember about being with Jimi Hendrix when he heard Bob Dylan’s John Wesley Harding album?

I got to know Hendrix a bit when he was becoming a sensation in London. You have to understand that in England in the ’60s, unlike America, everybody was all in one place: London. There were just for or five studios where we all worked, and three or four after hour clubs where we hung out. So everybody ran into everybody in a manner that would be hard to understand if you weren’t there.

I saw Hendrix at the Scotch of St. James when Chas Chandler was taking him around to sit in and jam with everybody, and I think McCartney was there that night. This guy gets up and starts playing and I'm like, “Holy shit! Who the fuck is this?”

And then he was sitting in at Blazes one night and I saw him sitting by himself and just sat down and started talking. He was a fan of Traffic, so we struck up a friendship and hung out a little bit and would sit around and play records. I got up and jammed with him a couple a few times best I could. We were all working in the same studio — Olympic — and using the same engineer — Eddie Kramer — and sessions would just back into each other. I was hanging with Jimi, who played bass guitar on almost the whole of Electric Ladyland. Noel [Redding] was out and Jimi and I were talking about me taking his place in the Experience.

How close did that come to happening?

Pretty close I think, but management put a stop to it. One night when we were hanging out, he got a call from a friend that she was having a little get together at her apartment and she had an advanced copy of John Wesley Harding, so we went over there and some of the guys from the Pretty Things were there. Everybody was wasted, and we just sat around and listened to the new Bob Dylan album and something caught Jimi’s attention: “All Along the Watchtower.” A few days later we were in the studio recording it.

"Noel was out and Jimi and I were talking about me taking his place in the Experience."

— Dave Mason

Is it correct that you played 12-string guitar on it?

Yes. Mitch Mitchell was playing drums and Jimi and I sat down facing each other, with Jimi on six-string acoustic and me on 12-string. It took me 10 or 11 takes to get the timing on the intro right, and Jimi easily could have just done it. I stayed and watched the whole session, with him putting bass and electric guitar on the track and it was one of the most incredible, inspiring musical experiences I’ve ever had. Absolutely inspiring to watch him work.

Was it immediately apparent that it was something you’d be talking about for the rest of your life?

Yes, of course. There are a lot of great guitar players — umpteen out there who can play rings around me — but there are no more Jimi Hendrix’s. The guy was just so innovative and what he did in the studio was incredible. He was getting ready to do something with Miles Davis when he died and it would have been phenomenal. He was something else.

Then you went to America and toured with Delaney Bramlett…

Who was incredible but could have these dark moods. And his band became Derek and the Dominos, and I was initially in that band.

Did you think that that was gonna become your next gig?

Yes. I knew all the guys and we worked well together but unbeknownst to me, the problem was that Jim Gordon got Eric into heroin and things just bogged down.

"The British invasion is an American story. We just copied everything, put a little something on it and sold it back to you all."

— Dave Mason

A lot of sitting around doing nothing?

Right. That was the problem for me, so I just went, “You know, guys, I'm out.” I've never touched the stuff and I didn't want to be around it. I was never into that laid-back junkie mentality, though it took me a long time and many people to understand what they were up to. My habit was the other way — stimulants. Like, “Let's get going!”

Then Derek and the Dominos went and recorded their first album in Miami and [producer] Tom Dowd said it was dead until Duane Allman showed up and kickstarted the sessions – another guy with a tremendous work ethic, and he basically replaced you. You were good friends with Gram Parsons after you came to California. Could you talk about him a little bit as a person and as a musician?

I met Gram in England when he was hanging around the Stones sessions. When I was unceremoniously dismissed from Traffic it felt like there was nothing in England for me, so I decided to go where all this music started: America. The British invasion is an American story. We just copied everything, put a little something on it and sold it back to you all.

You hung out a lot at Cass Elliot’s house in Laurel Canyon and you write about how the Manson murders hit close to home because of knowing some of the people.

Yeah, Sharon Tate and Roman Polanski and Amy Folger [all victims of the Manson Family] came over to Cass’s house a lot. Obviously, I didn’t know what was happening, but I had a sense of unease; I just thought that all this stuff was not going to end up well. I was never really a hippie. I basically felt like an outsider in my chosen profession, because I have a very methodical work ethic.

You wrote and played slide guitar on Delaney and Bonnie’s “Coming Home,” which is in open F, which you learned from Stephen Stills. Did you spend a lot of time playing with him?

Yes, we hung out and jammed quite a bit. Brilliant guitarist. I used to go up to the house when they were just forming Crosby Stills and Nash rehearsing every day just to hang out.

Just another example of you being there at a historical rock and roll moment. At what point did you realize that you're a lifer, that this is what you were going to do forever?

Pretty much from the beginning, when I was 17 or 18. It was pretty much a wing and a prayer. Damn the Torpedoes.

Dave Mason's autobiography, Only You Know & I Know, is out now from DTM Entertainment.

Alan Paul is the author of three books, Texas Flood: The Inside Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan, One Way Way Out: The Inside Story of the Allman Brothers Band – which were both New York Times bestsellers – and Big in China: My Unlikely Adventures Raising a Family, Playing the Blues and Becoming a Star in Beijing, a memoir about raising a family in Beijing and forming a Chinese blues band that toured the nation. He’s been associated with Guitar World for 30 years, serving as Managing Editor from 1991-96. He plays in two bands: Big in China and Friends of the Brothers, with Guitar World’s Andy Aledort.