“It was a way to kind of memorialize the folks that I lost”: Grieving the death of his grandparents and close friend Joey DeFrancesco, jazz guitar ace Dan Wilson found solace in creating his beautiful new album, Things Eternal

For this dazzling LP, Wilson recorded a stirring array of covers and originals, all the while channeling the lessons he's learned from George Benson, and approaching the material more like a drummer than a guitarist

There was no denying Dan Wilson’s talents, nor the diversity of his repertoire, when he released Vessel of Wood and Earth in 2021. They shone through on every track. The sheer speed, incendiary single-note flights, and swing factor that the Akron, Ohio–based guitarist demonstrated on tunes like “The Rhythm Section” and “The Reconstruction Beat” marked him as a new talent to watch, as did the impeccable, Pat Martino–esque picking technique he flashed on “Who Shot John.”

Elsewhere on that outing, his third as a leader, Wilson balanced those fleet-fingered numbers with two timely message songs in Marvin Gaye’s “Inner City Blues” and “Save the Children,” the latter grafted onto the stirring intro of John Coltrane’s “After the Rain.”

He lent a subtle touch of reharmonization to Stevie Wonder’s “Bird of Beauty,” then delved into an intimate duet reading of “Cry Me a River” with the soulful, gospel-influenced vocalist Joy Brown, and two other duets with bassist-producer Christian McBride on Pat Metheny’s buoyant “James” and the Ted Daffan country classic “Born to Lose,” a tune made famous by Ray Charles on his 1962 album, Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music. Indeed, Wilson seemed like the complete package.

Six years earlier, I made note of his talent when I had the honor of being on a panel of judges for the 2015 Wes Montgomery International Guitar Competition.

The five finalists who played that October day, backed by Pat Martino’s organ trio of Hammond B3 ace Pat Bianchi and drummer Carmen Intorre, were all accomplished young players with bright futures ahead of them. But two stood out from the pack: Wilson, who impressed the judges with his George Benson–esque single-note flurries and deep blues feel; and the eventual winner, Pasquale Grasso, who stunned with his incredible fluency and Joe Pass-ian command of the instrument.

Wilson would go on to join a group led by Joey DeFrancesco – he appeared on the late organist’s Grammy-nominated 2017 album, Project Freedom – and later toured with bassist Christian McBride’s Tip City. McBride would serve as producer on Vessels of Wood and Earth, releasing the album on his newly formed imprint Brother Mister Productions through Mack Avenue Music Group.

Now comes Things Eternal, the guitarist’s follow-up on Brother Mister/Mack Avenue. Co-produced by McBride, it once again showcases Wilson’s wide-ranging musical tastes in his unique takes on familiar tunes from the Beatles, Sting, Stevie Wonder, Michael Brecker, Freddie Hubbard, and McCoy Tyner, along with some inspired original compositions. And as before, the blazing Benson-esque single-note lines and Martino-style pick-every-note technique are very much in effect on his fourth overall effort as a leader.

Things Eternal once again showcases your musical eclecticism in tackling tunes by everyone from the Beatles, Stevie Wonder and Sting to Freddie Hubbard, McCoy Tyner, and Herbie Hancock.

Yeah, there’s so much stuff out there. And just to be clear, I’m always going to want to swing, I don’t want to lose that. That’s always going to be my foundation. But I’m definitely not going to ignore the myriad styles of music.

When I went to South Africa in 2018 with Joey DeFrancesco, I got a chance to talk to the people there and just kind of get their take on life and how they grew up. So many of them spoke six, seven languages. It’s something everybody did, so they’re able to communicate with more people. And that’s the way I look at music. I like to be musically multilingual, to be able to converse intelligently across musical styles.

That explains how Stevie Wonder’s “Smile, Please” fits so nicely next to Herbie Hancock’s “Tell Me a Bedtime Story” in the album’s sequencing.

Exactly. And of course, that message for “Smile, Please” is good to hear when you’re grieving. And that song has all the elements that I look for in music – it has a well-constructed melody, interesting harmony, and a groove. That’s all I need. So, Stevie Wonder? I put him right right up there with Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn and composers like that.

I’m curious about your decision to use Glenn Zaleski on Fender Rhodes throughout this new recording rather than having him play piano.

That was completely by accident. The piano that they had at the studio was in pretty poor condition. I planned on having Glenn on Fender Rhodes for just some of the tracks, but he played the piano in the studio and he was like, “Yeah, man, we got to do the whole session on Rhodes.” He said, “This piano’s terrible.”

So it was kind of a happy accident, and it really set the tone for the entire record. It just gave the album a different vibe, especially coming from my last record.

You’re on fire on Freddie Hubbard’s “Birdlike,” right out of the gate. It reminded me of George Benson’s “The Cooker,” that opening track from his great 1967 album, The George Benson Cookbook.

Oh man! [He sings Benson’s solo on that uptempo romp note for note.] I just saw George this past week. We were talking about Cookbook and It’s Uptown. Man, every time I hear those records I feel like I’m 13 years old again, with my ear by the speaker, trying to figure out what’s going on.

You obviously have a friendship with George Benson. Did you ever sit down and study with him?

I feel like I’ve studied with Benson, because I have studied his playing on records. But we never sat down and went through things. That would be a dream come true, but it hasn’t happened yet.

What’s the story behind the title of your tune “Since a Hatchet Was a Hammer”? That’s an expression you don’t hear much anymore.

That came from my great-aunt Mary. She was 98 when she passed. I went to visit her in the nursing home once and I was like, “How you doing, Aunt Mary?” And she said, “Is that Dan? I haven’t seen that boy since a hatchet was a hammer.”

Throughout this new record, I’m hearing that easy doubling up of the tempo on your single-note playing. You have it down so well. To my ear it’s Benson-esque, or maybe even Pat Martino–esque. It’s definitely coming out of that pick-every-note school, as opposed to a hammer-on legato style of playing.

Well, I was a drummer first, so I always wanted that percussive attack on the instrument. I always wanted to be able to pick every note. It’s not always the best musical decision to pick every note, but that’s the key for me. I guess I’m coming from a different perspective. I love drums more than anything, and that’s how I approach my instrument.

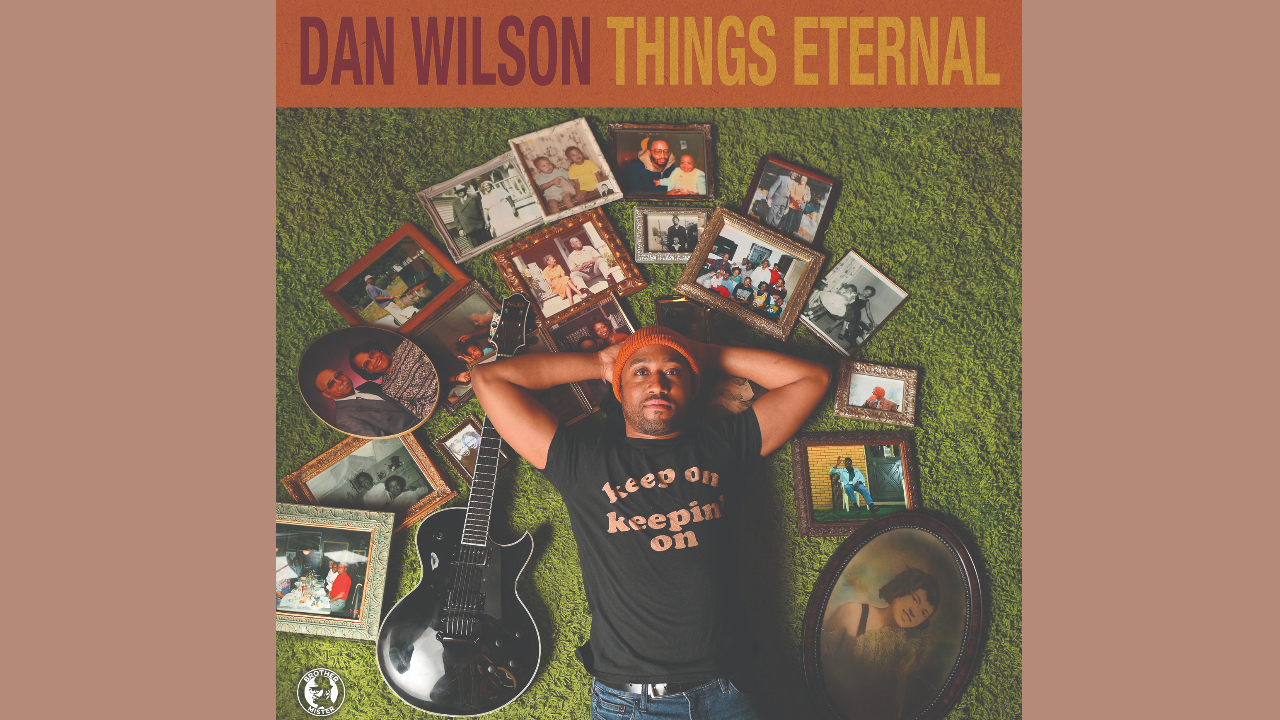

Speaking of your instrument, what is that black guitar pictured on the album cover?

That’s the Pat Martino Signature Model, from Benedetto. When I got the endorsement from Benedetto, they sent me several guitars to play, and I tested them out on Joey’s gig and on the McBride gig. I had trouble with some of them feeding back, so I couldn’t really use them on those gigs. But then I tried out that Pat Martino model and settled on that one.

I’ve had some glorious moments onstage with that guitar. When I started with Benedetto, I first tried out the Benny, which was really nice, but it fed back too much. And, like I was saying, I needed to have something that I could speak different languages with.

Benedetto had another one called the GA-35, which was like a Gibson ES-335. But they discontinued that model, so they were like, “Why don’t you try the Pat Martino Signature Model?” I played that and I was like, 'Whoa! Yup, this is it right here'.

Stevie Wonder? I put him up there with Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn and composers like that

What guitars did you go through before you even got involved with Benedetto?

I had a Gibson Howard Roberts Fusion guitar, and then I had a Gibson ES-446. I loved that guitar, but I broke it and I got it repaired, but it was never the same afterward. So I sold it. I still have the Howard Roberts. That guitar has great sentimental value, because when I started kind of making gains on the instrument, my uncle gave it to me.

So you never went through a period of playing solidbodies? You went right to Howard Roberts?

Well, my first guitar was a cheap Fender Squier, and then I went to a Joe Pass guitar. And then I got the Howard Roberts.

What gauge strings do you have on your Benedetto Pat Martino Signature? I know that Pat Martino had very heavy-gauge strings – 15s.

I got 11s. Yeah, Mr. Benson was talking about that last week. He was like, “Brother, if you tried to play Pat Martino’s guitar you wouldn’t be able to play it. He had ropes on it.” Yeah, 15s… I couldn’t do it. I guess he wanted the instrument to have some fight in it.

Your soloing throughout Things Eternal is incredibly accomplished. Your single-note flow on tunes like “Tell Me a Bedtime Story” and “Birdlike” is just astounding. Where do you get that from?

Honestly, that comes from lessons I learned before I ever set foot in a jazz club. Growing up in church, I was always able to play single lines easily, but they weren’t necessarily making much sense. They were fast and precise, but the content was kind of lacking.

There were some great, great guitar players in the church that I came up in. I could name 30 of them offhand. So, you know, I was getting my butt kicked. I was getting a lot of those lessons like, “No, you gotta play melodies with those lines. They can’t just be fast.”

They’d pull me aside and go, “Look, Brother Wilson, I’m glad you can play that stuff really fast and clear, but it has to make sense. It just sounds like you’re running up and down the neck because you can.”

But eventually, as I matured and grew under their tutelage, I started to realize the value in being able to craft a melody in my solos. Because nobody can remember the intricate details of a super-long line, but you may remember a melody that pops out in the middle of a solo.

The title track from Things Eternal represents another side of your playing. It’s a gorgeous ballad that showcases your accompaniment skills behind a vocalist, à la Joe Pass with Ella Fitzgerald.

Oh, man! I love those records they did together. I’ve always loved to play behind a singer. One of my mentors is Russell Malone, and I think that’s one of his greatest skills. And I learned a ton just from listening to him accompany Diana Krall. He also worked with Nancy Wilson, Aretha Franklin, Gladys Knight... So just listening to him and gaining wisdom on how to play behind a vocalist has been really valuable for me. I’ve sat down with Russell with two guitars. I play with him quite a bit. I learned a ton from him.

I was surprised by your gospel-tinged interpretation of that Sting tune, “Let Your Soul Be Your Pilot.”

Yeah, when I listened to the lyrics, I immediately thought, “This is not just Sting, this is Rev. Gordon Sumner.” [Gordon Sumner is Sting’s birth name.] I mean, he brought that from somewhere else.

So when I heard those lyrics [to Sting’s “Let Your Soul Be Your Pilot”] I was like, “Oh, yeah, Sting’s been in somebody’s church!”

When I heard Sting’s original recording of it, in 2021, it was three days before my son was born and my dad just had a major stroke. He was paralyzed on the whole right side of his body and he is just now getting it back and learning how to walk again. So it was a period when some heavy stuff was going on, and I was just grappling with those realities. And the lyrics to that tune really kind of harkened back to some lessons I learned in my upbringing.

It says: “When the doctors failed to heal you, when no medicine chest can make you well / when no counsel leads to comfort, when there are no more lies they can tell / When there’s no more information and the compass spins between heaven and hell / Let your soul be your pilot and it’ll guide you well.”

So when I heard those lyrics, I was like, “Oh, yeah, Sting’s been in somebody’s church!”

So I put Jessica Yafanaro on the melody, and that’s why my solo was not that extensive. Because my feeling was, This is not the time to be playing too much stuff. I wanted the message of the lyric to shine though. And I’m thankful that I was able to call up my man Nigel Hall, because he really brought that kind of raw gospel element I was looking for.

You wrote some equally thoughtful lyrics on your very moving ballad “Things Eternal,” which is sung beautifully by Jessica Yafanaro. The line that resonates with me is, “Things on the surface, they all pass away/Have hope for tomorrow but live today. Things eternal endure always.”

Those lyrics kind of came to me in a fever dream that I had. I had a really bad fever and I sweating in my sleep, and then I had this really vivid dream that all my relatives were around the table and we were having dinner and I was able to talk to my grandmother, who had passed. It was crazy, because it was a really vivid dream, like I was really there.

That happened a couple of times, and then one of the times when I woke up from this fever dream, I just started writing down these lyrics. And that’s how the song came about.

So that was kind of therapeutic for me, dealing with all the loss I had been experiencing. My grandmother had passed, and then I lost my grandfather when I was on the road with Joey DeFrancesco. And then Joey’s sudden, untimely death last summer was another shot. So for a couple of months I was kind of just walking around in a fog, and my wife was like, “Hey, it’s like you’re here, but you’re not here.”

At that point I was like, Okay, I gotta get this under control. So I started seeing a grief counselor and writing this music at the same time. And this tune was a way to kind of memorialize the folks that I lost and to just get back into a good headspace again. It was a really important message that I wanted to get across, and I think in the future I’ll be writing a lot more lyrics.

You recently participated in a Joey DeFrancesco tribute concert in Joey’s hometown of Phoenix. What was that like?

Man, it was really an emotional experience. I had a tough time keeping it together. But there was a lot of joy in the room. It was good, because the grief could have, like, sucked the air out of the room, but just being around guys like Troy Roberts, Lewis Nash, and Ronnie Foster and seeing how much love they have for Joey – that made it a joyful experience.

It was one of the first times that I’ve shed tears on the stage. Because you start playing and you get to thinking about how much he did for us, musically, and for our careers and personally. It’s just overwhelming sometimes.

But Joey, when he got down to business onstage, there was nothing like it. And the hook-up that he had in our band with drummer Jason Brown – it was like they were separated at birth. They shared a brain. A lot of times they wouldn’t even be looking at each other and they’d just be hitting the same thing over and over. It was crazy to see. I had a beautiful time in Joey’s band. I would not trade it for the world.

Things Eternal by Dan Wilson is out now and available to buy or stream.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Bill Milkowski's first piece for Guitar Player was a profile on fellow Milwaukee native Daryl Stuermer, which appeared in the September 1976 issue. Over the decades he contributed numerous pieces to GP while also freelancing for various other music magazines. Bill is the author of biographies on Jaco Pastorius, Pat Martino, Keith Richards and Michael Brecker. He received the Jazz Journalist Association's Lifetime Achievement Award in 2011 and was a 2015 recipient of the Montreal Jazz Festival's Bruce Lundvall Award presented to a non-musician who has made an impact on the world of jazz or contributed to its development through their work in the performing arts, the recording industry or the media.

"This 'Bohemian Rhapsody' will be hard to beat in the years to come! I'm awestruck.” Brian May makes a surprise appearance at Coachella to perform Queen's hit with Benson Boone

“We’re Liverpool boys, and they say Liverpool is the capital of Ireland.” Paul McCartney explains how the Beatles introduced harmonized guitar leads to rock and roll with one remarkable song