“Noel’s process is purely guitar. He’s so in love with the chords, and he was cycling through and through... He wouldn’t stop until he was satisfied”: How Noel Gallagher and Beck helped bring the Black Keys' latest funky full-length, Ohio Players, to life

The Black Keys began life as a bare-bones two-piece, but, as Dan Auerbach tells GP, collaboration and an open musical mind have expanded the duo's sound to thrilling new heights

At the start of the Black Keys’ latest album, Ohio Players, singer/guitarist Dan Auerbach declares that he’s going to “spend the rest of my days in the middle of nowhere.” He’s joking, of course.

It’s certainly been an eventful journey for Auerbach and drummer Patrick Carney since the pair met as childhood neighbors in Akron, Ohio. Both have musical family backgrounds that stoked their own interests, and diverse ones at that. Auerbach’s cousin Robert Quine was one of New York City’s top guns, playing with Lou Reed, Richard Hell & the Voidoids, Tom Waits, Matthew Sweet, and many others.

Carney’s uncle Ralph Carney, meanwhile, was a saxophonist who played with Waits, among others. Auerbach and Carney seemed strange bedfellows as teens – the former was a jock, the latter a self-described outsider – but by 1996 they were playing together and recording their experiments on Carney’s portable four-track recorder.

“When we get together now, it’s still the same as it was then, man,” Auerbach notes from within the vintage gear–oriented “embarrassment of riches” he keeps at his Easy Eye Sound studio in Nashville. “We don’t even talk about it. We don’t have any preconceived notions of how it’s gonna go. We just start playing and making music and doing what comes naturally, just like we were doing when we were 16.”

It’s fair to say it’s worked out well for the Black Keys. They’ve released a dozen studio albums (including the double-Platinum Brothers in 2010 and El Camino in 2011), a lauded Blakroc collaboration with Damon Dash, landed 10 singles in the Top 20 of Billboard’s Hot Rock & Alternative Songs chart, and won five Grammy Awards from 16 nominations.

Even more impressive has been the duo’s sonic evolution. The raw guitar-and-drums grit of 2002’s The Big Come Up has developed into more sophisticated and expansive soundscapes over the years, with the likes of Danger Mouse helping to stretch how Auerbach and Carney view the Black Keys as a musical palette, introducing more instruments, and musicians, to advance their aesthetic sensibilities beyond the blues roots that provided the group’s launchpad.

They still love that stuff, mind you – some evidence being 2021’s Mississippi hill country immersion Delta Kream – but the Keys’ unapologetic sense of curiosity and adventurous ambitions have goosed Auerbach and Carney into realms beyond.

That’s certainly the case with Ohio Players. The Keys’ fourth album since ending their five-year hiatus in 2019, it further mines the collaborative vein Auerbach and Carney struck with Dropout Boogie in 2022. That album was the first on which they fully embraced input from outside writers, including Face to Face alumnus and Kings of Leon producer Angelo Petraglia and, on one track, ZZ Top’s Billy Gibbons.

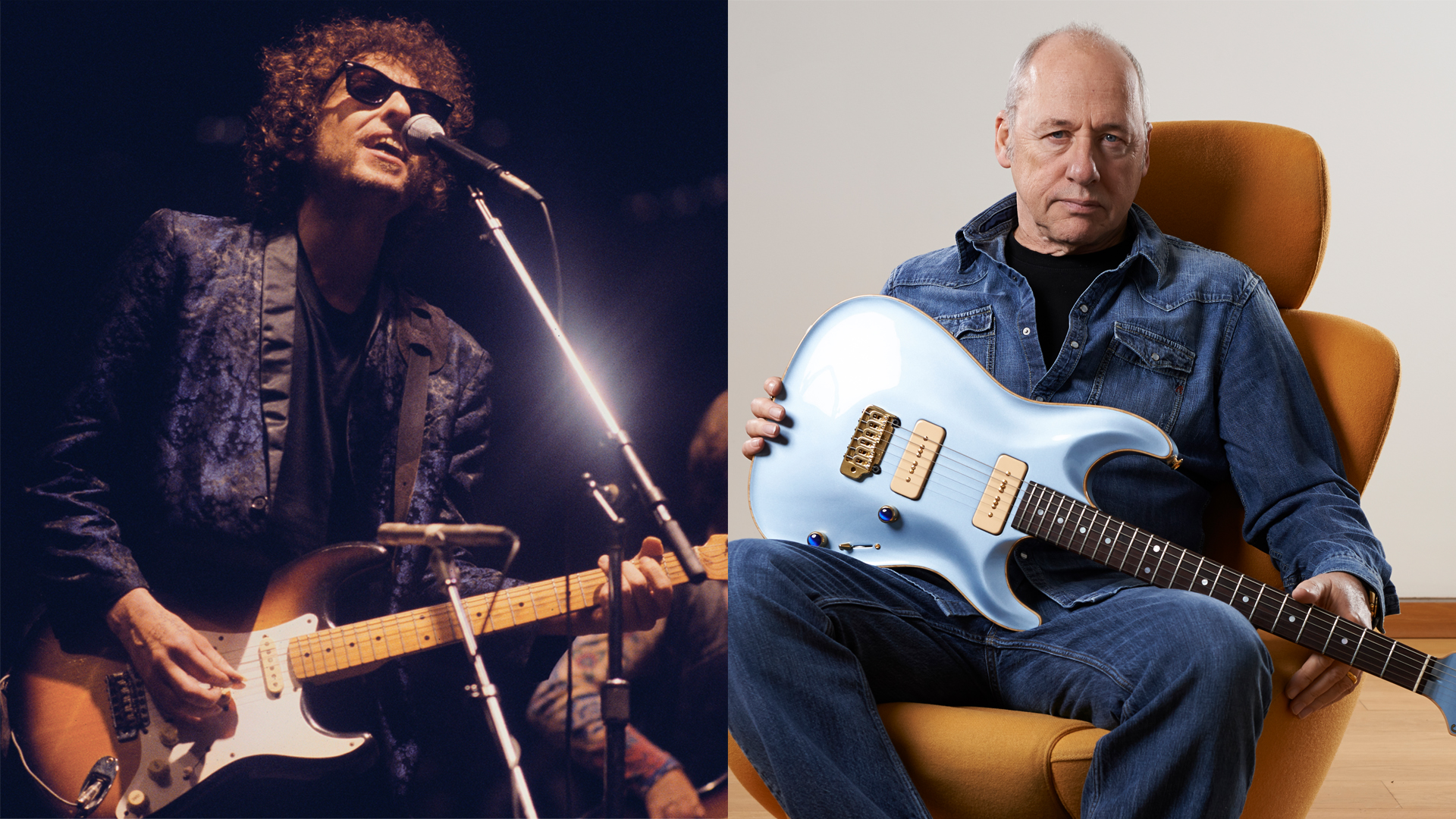

Ohio Players ventures even further on its 14 tracks, with Beck onboard for seven and Noel Gallagher joining for another three songs. Dan the Automator performs on two cuts, and Memphis rappers Juicy J (of Three 6 Mafia) and Lil Noid lend their voices to the proceedings. Leon Michels – from Auerbach’s other band, the Arcs – appears as well, along with hit-making producer Greg Kurstin and members of Auerbach’s Easy Eye cadre, most notably fellow Ohioan Tom Bukovac, who channels his best George Harrison on the Gallagher track On the Game.

Ohio Players is, in fact, a combination music lab and cosmic carnival that’s serious creative business. It’s also a lot of fun, in some ways akin to Auerbach and Carney’s occasional Record Hang DJ sessions – dance parties at which they spin seven-inch vinyl. The thrill ride begins with the thick bass notes of This Is Nowhere, while the soul-inflected Don’t Let Me Go grooves out of a ’60s cocktail lounge.

Paper Crown, meanwhile, is funky enough to give the original Ohio Players a run for their money, and the libidinous Please Me (Til I’m Satisfied) is a pure, primal garage stomp. Live Till I Die offers a prototypical fusion of Beck-style psychedelia and Crazy Horse riff attack, while Beautiful People (Stay High) would fit on the former's 1996 album, Odelay.

Even without liner notes, it’s not hard to figure out which tracks were recorded with whom, but the Auerbach-Carney filter ensures they fit best on a Black Keys record. And from what Auerbach tells Guitar Player, it’s clear that Ohio Players was as much fun to make as it is to listen to.

This is another very different-sounding Black Keys record. That’s how you guys roll now, isn’t it?

“I guess so. I feel like every album is a different scenario, and we get a different outcome. A lot of people I like are the same way, I think. But ever since we started, there’s been something about playing music with Pat that gave me confidence. If you listen to our tapes from when we were 16, 17, I swear it sounds a lot like some of the songs on Dropout Boogie. We haven’t changed all that much.

“We don’t have any preconceived notions of how it’s gonna go. We just start recording and making music and doing what comes naturally. That’s really what we’ve done since we were teenagers.”

You work at a pretty busy clip, with the Black Keys and all the other Easy Eye stuff. Did you sit down and say, ‘Okay, time to start the new Black Keys record,’ or something like that?

“Well, you know, we never stopped recording after we did the last album. We just kept going. One of the things we were interested in doing was getting friends in to work with us, just for fun, to see what would happen, because we haven’t done that very often. The whole musical landscape of Nashville is based on teamwork, but Pat and I had barely dipped our toes into that stuff, so we started to reach out to people. The collaborative process played a bigger role this time than it ever has.”

Beck has the most prominent presence on Ohio Players.

“He was the first person we reached out to. He was gonna be in town, so we booked a couple days in the studio, and it was so much fun. The first day we got together, we wrote This Is Nowhere, and it just popped right out. It was Pat and I doing the music for the most part on that one, and Beck came in to help with melody and lyrics.”

Did these collaborations feel like an outgrowth of what you started with Dropout Boogie?

“Sort of, yeah. It was like we’d just barely done it there, and now it was, ‘Who do we love that makes really cool records, who writes great songs?’ So it was Beck, and then we thought about Noel Gallagher, and we reached out to him and he said, ‘Sure!’ We were excited.”

But you had to come to him.

“[laughs] we released that Arcs album [2023’s Electrophonic Chronic], and Leon [Michels] and I were gonna be in London doing some promotion. So Pat came with us and we presented a Record Hang, and then we went into Toe Rag Studios [an eight-track tape studio in London] with Noel and wrote three songs in three days. And it was a blast.

“We wrote those songs together in a room, and Noel had his [1963] Gretsch [6210 Chet Atkins], I had a guitar and a bass, Leon was on keyboard, and Pat was playing drums. We were in a circle – Toe Rag is very, very small – and it was a really amazing experience to watch Noel cycle through chords. To just, like, be there. We would patiently sit back and let him do his thing, and it was amazing to watch his wheels turn in real time.”

Noel’s process is purely guitar. He’s just so in love with the chords, and he was just cycling through and through and through, and that’s how he would find his melodies. He wouldn’t stop until he was satisfied

How would it work once he found the chords he wanted to use?

“Well, On the Game is one of my favorite songs on the record, and that’s a live performance with Noel. That one popped out very easily. We were just improvising melodies into the mic, and it took shape very quickly. It was kind of miraculous, to be honest.”

It must feel nice to be so far into this as a recording career and still have those moments of surprise and, it sounds like, even awe.

“Absolutely. We’re just so blessed to even be able to do this kind of thing, to have the agency. It’s like this is the real payoff for all the work we’ve done all these years, to be able to call people like that up and have that happen. We look up to those guys, Beck and Noel in particular. It was just amazing to get to collaborate with them.”

What kind of insight did you glean about them and their processes?

“You know, Noel’s process is purely guitar. He’s just so in love with the chords, and he was just cycling through and through and through, and that’s how he would find his melodies. He wouldn’t stop until he was satisfied. It never sounded right to him until it did, and that’s when we would move on. But we couldn’t move on until he got that good feeling.

“With Beck, he came in and we kinda had the music done; we had a framework. But he’d come in, and it was like a spigot when it’s fully open. It’s like pure creativity, and it doesn’t stop. It’s really remarkable. He’ll write verses for the song, and they’ll be really beautiful, but then he’ll say, ‘You know what? Save that. I’ve got other ideas,’ and he’ll write a whole other song on top of that one. It’s crazy. He’s so prolific, the way he can write. It’s amazing to watch.”

You mentioned how self-contained the Black Keys were, especially at the start of your career. What did you and Pat have to change about yourselves to be open to these kinds of collaborations?

“We had to be in a band for 20 years, honestly. We are only now able to do this type of thing. I know we couldn’t have done it 10 years ago, 15 years ago. It wouldn’t have been possible for us, ’cause we were just too in our own heads, insecure or whatever. I think we’re just a lot better at it now.”

We weren’t trying to make a record that sounded old, but we wanted to have the feeling you get when you find the right records and play them in a club, and the energy that you get from that

What role did the hiatus play in getting you to that point?

“Man, it was really nice to take a break and not feel like every time I saw Pat there was some grueling work involved. Now our relationship is better than it’s ever been, and it has a lot to do with hanging out and spinning records, collecting 45s and playing records at these Record Hangs we’ve been doing. Those were a huge influence on this album in particular.”

How so?

“We weren’t trying to make a record that sounded old, but we wanted to have the feeling you get when you find the right records and play them in a club, and the energy that you get from that. We wanted that kind of party atmosphere.”

Were there any particular records that tracked directly into songs on the album?

“I’m Alive by Johnny Thunders. That was one record that hit us over the head right in the middle of making this album. But we didn’t try to rip it off in any way. It was just the feeling of that record, and the directness. We would just always go to it as a reference, like, ‘Are we in that ballpark?’”

What came as surprises on the album?

“I played some gear at Toe Rag, some European ’60s guitars – I forget what they were – that sounded incredible. The bass that I played sounded so good out of this little Watkins amp. That’s the sound that’s on this record. My buddy Tom Bukovac from Cleveland plays guitar on the record in places here and there, and I love what he added. He plays this big ol’ honkin’ guitar hook on On the Game that’s amazing.

“It was the first or second take. I played him the song one time, and he goes in and just plays that. It’s like he knows what needs to be there.”

Isn’t that a bit like throwing down the gauntlet, to have other guitarists playing alongside you?

“Oh, it’s amazing. These are people whose playing I love. Tommy Brenneck plays on the William Bell cover, I Forgot to Be Your Lover. The intro guitar’s by Tommy. I’ve done a bunch of sessions with him, and he’s just an amazing producer, musician, and guitar player. I get inspired being around all these guys, and I love to hear what they get out of what we’ve done. It’s always interesting to me.

“The guitar Tom plays on Fever Tree is crazy. I played one thing and he played on the other beats – the opposite beats – and it locked in. It was so cool.”

You mention I Forgot to Be Your Lover, which is the only cover on the album. How did you decide on that?

“It’s always been one of our favorite songs, and Pat suggested we cover it. We were in Valentine Studios in L.A., which is like a time-capsule studio that was built in the ’60s. Someone found it a few years ago and it had never been touched.

“I’m sure being in that space had a lot to do with that decision, but it’s always been one of our favorite songs, and we had Tommy there, and we had Kelly Finnigan, who sings harmony and plays the Hammond. So it was like, ‘Yeah, let’s do it. This’ll be fun.’”

Was there any different or particularly interesting gear used on the album?

“No. I mean, we would just use whatever tool was necessary for the song. We have an embarrassment of riches here at the studio, so it’s like any sound we want with any amp combination, we have it.

“We’re kinda ready to do it. I don’t even think about it anymore. We can switch so quickly between the sounds that it’s not a big deal. There’s Flot-A-Tone amps, there’s Magnatone true vibratos, old tube amps. The [Fender] Tweed Deluxe got a lot of work with the spring reverb that my buddy makes. We would switch all over the place, all the time. Whatever the song called for.”

You have these Memphis rappers, Juicy J and Lil Noid, on some tracks. What’s your path to them?

“I’d just gotten into Memphis rap a few years ago. I knew about Three 6 Mafia [Juicy J’s hip-hop group], but only their big songs that were on major labels. So I didn’t know that this whole world of Memphis rap existed, but it didn’t exist on Apple or Spotify; it’s only on fan uploads to YouTube from cassette tapes, and there’s absolutely classic albums there.

“So, being a lifelong rap fan and realizing there’s this whole subcategory of rap, this family tree that I’d never even heard of but was right in my wheelhouse – it kind of blew me away, and I started obsessively listening to it. For example, Lil Noid’s Paranoid Funk feels like a classic album the same way Dr. Dre’s The Chronic does.

“So, we were in the studio and constantly listening to Lil Noid, and I said, ‘We should get him on a track, just for fun.’ We reached out to him, and he was just down the road in Memphis. So he came in and we created a bed for him based on one of the tracks, in the same way we did when we made the Blakroc album.

“It was just an extension of that. But, it felt awkward to only have one interplay like that, so we reached out to J and we sent him the track, and he returned his vocals and the scratching he did, like, the next day. It was so fast it was crazy. And Juicy J was the guy who found Lil Noid when he was 15 and put him on a mixtape, so it’s almost like this weird little circle there that I love.”

Ohio Players has a couple of meanings as a title.

“That was Pat’s idea. We just both thought it was really fun. We are Ohio players, literally. And we love the Ohio Players. We reached out and asked them if it would be cool to use the name, and they loved it. We were just so honored. It’s all fun, really.”

There’s a bowling motif to the album’s cover and graphics. Do you roll ’em?

“Not really. I’m at the stage now that, if I go bowling, my arm is sore for two days afterward. I’m really out of bowling shape, although something tells me I’ve got to get back into it.”

Have you and Pat continued to not stop recording since Ohio Players was finished?

“[laughs] Yeah, we’ve continued to not stop recording. We had Kenny Brown and Eric Deaton [from Delta Kream] up here to play some music, just for fun. I’m always in the studio working on stuff.

“We just had the [Boulder-based rock trio] Velveteers in here; Pat and I worked with them on a song together, actually, which was the first time we did that, and that was really cool. We just made a really heavy record [as producer] with [indie garage-punk quartet] Shannon and the Clams.

“It’s a lot of fun and it’s really cool to be able to work with the people who were our heroes, and then it’s amazing to work with people like John Muq [a Ugandan singer-songwriter and producer living in Austin] and [singer] Britti, who are making their very first albums. There’s all kinds of records – just a lot of beautiful music going on.”

Do you maintain a wish list or bucket list of additional things you’d still like to do?

“I’m the kind of person who likes to just try something and see what happens. That’s the best way to be. You can’t think about this shit too much. I’m all about putting Pat and myself into different situations to see what happens. We have strong enough personalities that we never have to worry about ourselves going too far astray.

“Whenever we work with someone, it’s always a real collaboration. I love that we’re comfortable enough to do that kind of thing. I think that means it’s gonna be more fun and exciting to be able to try all this stuff, whatever we want to do.

“The older we get – and the more we both get to make records with other people and work on outside projects and then come back to the Black Keys – the more we appreciate what it is we’ve been given. It’s kind of like the gift of being able to have this musical connection.”

- The Black Keys' new album, Ohio Players, is available to purchase or stream now.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Gary Graff is an award-winning Detroit-based music journalist and author who writes for a variety of print, online and broadcast outlets. He has written and collaborated on books about Alice Cooper, Neil Young, Bob Seger, Bruce Springsteen and Rock 'n' Roll Myths. He's also the founding editor of the award-winning MusicHound Essential Album Guide series and of the new 501 Essential Albums series. Graff is also a co-founder and co-producer of the annual Detroit Music Awards.

“I knew he was going to be somebody then. He had that star quality”: Ritchie Blackmore on his first meeting with Jimmy Page and early recording sessions with Jeff Beck

“He used to send me to my room to practice my vibrato.” His father is the late Irish blues guitar great Gary Moore. But Jack Moore is cutting his own path with a Les Paul in his hands