Chrissie Hynde Gets the Band Back Together and Takes No Prisoners as the Pretenders Return with "Hate for Sale"

Chrissie Hynde and James Walbourne on writing, youth culture, and capturing the Pretenders' rock 'n' roll energy on record.

Chrissie Hynde has always been clear-eyed about her life’s path. “Someone once asked, ‘What would you be doing if you weren’t in a band?,’” the 68-year-old Pretenders leader tells Guitar Player.

“And the answer is, ‘I’d be in a band.’” She laughs. “That sort of sums that up, you know?” Indeed it does. And it also makes the newest release from the Pretenders, Hate for Sale (BMG), all the more special.

Not only is it a rocking, raucous record, it’s also Hynde’s first offering with her full touring band, which includes guitarist James Walbourne, bassist Nick Wilkinson and returning original drummer Martin Chambers.

“I’ve done what I’ve done over the years,” Hynde says, referring to her two solo albums, 2014’s Stockholm and 2019’s Valve Bone Woe, as well as the 2016 Pretenders album, Alone, recorded with Black Keys frontman Dan Auerbach and a host of Nashville session players and guests.

This album really is about this band. And that’s what I love about it — it’s a real band sound

Chrissie Hynde

“But it is only fair to say that all this time I wanted to play with this touring band that I love. In fact, I shouldn’t even call it a touring band — this is the Pretenders. And we really seemed to knock it out of the ballpark.”

You can say that again. Hate for Sale is classic Pretenders, roaring out of the gate, following a raggedy false start, with the garage-punk title track, on which Hynde snarls over barbed-wire guitars and bleating harmonica about a teeth-capped, chest-waxed gym rat with “money in the band and coke in his pocket.”

From there, we get everything from the glam-stomping “Turf Accountant Daddy” to the rockabilly romp “Didn’t Want to Be This Lonely,” the R&B/soul jam “You Can’t Hurt a Fool” and the slinky, ultra-melodic rocker “The Buzz,” which hearkens back, in the very best ways, to archetypal Pretenders tracks like “Kid” and “Show Me.”

And while, as always, Hynde’s cool vocal and agitated Tele are the focus of these songs, she credits the music’s very existence to the presence of Walbourne, who has served as a member of the Pretenders for these past 12 years and who she calls her “guitar hero.”

“James is definitive,” Hynde says of Walbourne, who in addition to his own band, the Rails, has also worked with Jerry Lee Lewis, the Kinks’ Ray Davies and the Pogues, among many others.

“I haven’t seen anyone else who can do what he does. And this time around we wrote all the songs together, which we’ve never done before. We went into a little pre-coronavirus lockdown in France, and the songs started flying out. It was great.”

Walbourne concurs. “When we got going, it happened quickly,” he says. “You get over the initial nerves and realize you can work together. Chrissie would write reams and reams of lyrics, and I would go over it and see what would hit me and then try and put some music to them. We just went at it like that until we got it right.”

As for the harder-edged sound this time around? “That’s just the band,” Walbourne says. “When Chrissie, Martin, Nick and I get together, the punkier thing just happens. That’s how we play!”

“This album really is about this band,” Hynde adds. “And that’s what I love about it — it’s a real band sound. And if anything, people might not know that they’re missing that.” She pauses. “But believe me, they’re missing it.”

The only reason to really play something in an unusual time signature is if you don’t know what you’re doing and you can’t play in 4/4

Chrissie Hynde

Chrissie, you’ve stressed the importance of capturing the band sound on Hate for Sale, and it comes through straightaway on the title track, which starts the album off with what sounds like a mistake, before everyone regroups and comes crashing back in together.

Chrissie Hynde: [Hate for Sale producer] Stephen Street put that on there, just for a laugh. That was a cock-up in the studio, and he left it on. And you know, the thing about mistakes and accidents is they’re the things that are unique. You can’t be contrived with that stuff, because if it’s contrived it’s not natural.

Like, if you try to contrive an unusual time signature, it just becomes prog-rock. The only reason to really play something in an unusual time signature is if you don’t know what you’re doing and you can’t play in 4/4 time. [laughs] Like I did on my first album. People were like, “Oh, you have these time signatures that are unusual.” I said, “Oh, are they?”

“Hate for Sale” really defines the overall vibe of the album. How did that song come together?

James Walbourne: The song itself came together with a lyric. Chrissie gave me some words for it, and they sounded angry. So I just started playing that riff, and that was it. And that’s the sort of song this band can play straightaway, really. It’s in our wheelhouse. Just a good-old punk song.

Chrissie just lets me do what I want guitar-wise, within reason, obviously. But I have enormous freedom to just play

James Walbourne

Hynde: We really wanted to make a punk-sounding album, and you just can’t have a punk-sounding album with virtuoso players. It’s an oxymoron. It doesn’t exist. You have to have people who can’t play very good to be truly punk. [laughs] And my guys all can play!

In fact, I’m probably the punk element, because my playing is rougher than theirs. So that always adds something. But I have to say, any excellence on this album is totally down to James Walbourne’s guitar. I’m totally an afterthought.

James, you’ve played in so many bands and projects over the years. What do you like about being in the Pretenders?

Walbourne: Oh, where, can I start? One thing is that, when I joined the band, Chrissie never wanted me to play what was on the records. And thank God, because I couldn’t! But she just lets me do what I want guitar-wise, within reason, obviously.

But I have enormous freedom to just play. As for what’s unique about it compared to other bands? I don’t know. Everyone’s quite funny. We do have a good laugh, you know? It’s great fun, really.

Chrissie, you called yourself “an afterthought” on the record, but clearly your playing is so instrumental to the Pretenders’ sound.

Hynde: Yes, absolutely. I always try to sneak out of it, but I have been told on every album I’ve done, “How you play is part of it, and it’s important.” And as a matter of fact, recently James and I started recording some Bob Dylan songs over the phone. I’ll do the rhythm track and send it to him, he embellishes it with his guitar, and he sends it back.

Because I have a lot of time on my hands, I’ve really been sitting down with the guitar and trying to find the right key, the right vibe, the right tempo, how I want to do it.

And so I’ve really rediscovered falling back in love with playing guitar. Because when you surround yourself with people that are better than you, which is what I’ve always done — it’s the secret to my success, you know? — you start to back out a little bit.

You go, “Ah, you guys do it.” And that’s a mistake. But me sitting down with a guitar and doing these Dylan songs, I feel like I’m 15 with my guitar again. It’s really been a revelation.

I’ve really rediscovered falling back in love with playing guitar

Chrissie Hynde

Can you tell me what your main setup was on the record?

Hynde: I probably cannot. [laughs] I probably just played my Tele though a Fender Twin.

James, how about you?

Walbourne: I used a 1963 [Gibson] SG Junior, which has weirdly become sort of my main axe of late. And I played a Tele on some of it, as well as a black 1957 Strat that Chrissie gave me a few years ago. And there was a Gibson J-45 from 2009 for the acoustic bits. It was fairly simple. Then for amps I had a pair of ’68 Fender Deluxe Reverb reissues. And for pedals I’ve got a few Strymons.

Which ones in particular?

Walbourne: I have the Riverside [Multistage Drive]. I use that live all the time. And I have the Mobius [Multidimensional Modulation], the Deco [Tape Saturation & Doubletracker] and a TimeLine [Multidimensional Delay]. You get one and you can’t stop buying them!

How did you approach your leads? On “Hate for Sale” and “Didn’t Want to Be This Lonely,” they sound so of a piece with the vibe of the song, both musically and lyrically.

Walbourne: I guess it came from the writing. Chrissie would give me the lyrics, and I would put earphones on and plug my electric guitar in at home. I’d get a sound and just shout down a microphone with the guitars really loud in my headphones.

I’ve been really enjoying that because you don’t piss off the neighbors… at least I don’t think I do. [laughs] It’s like you’re playing in a loud rock club in your head, but the parts come from the vocals and the lyrics. They fit around that as opposed to me putting them on later. They were there in the songs at the beginning.

Even if I write something about myself, it’s going to speak for a lot of people, especially when you’re talking about something emotional.

Chrissie Hynde

Another song that stands out to me is “You Can’t Hurt a Fool.” It has such a great old-school R&B sound to it. What can you tell me about it?

Hynde: That’s probably the most crafted song on the record. James had that title, and I said, “That’s a f*cking great title.” So I really thought about that song. And I know we call a lot of music R&B, but anyone from the ’60s knows that the R&B we listened to then has zero to do with what we hear now.

You listen to Joe Tex and you listen to any modern act, and you will not find a similarity. However, when I think of R&B, I think of old-school — all these great vocalists and all the great arrangements. And I was really thinking about Lou Rawls. I was thinking about Otis Redding.

That’s what we wanted to go for. So we spent a lot of time trying to get that one right. And lyrically, clearly it’s autobiographical. Of course I’m talking about myself. But I could be talking about anyone.

So do you feel, as the song says, “too old to know better and too young for your age”?

Hynde: Oh, absolutely! But anything that I feel — just like any thought I have or anything I say — can’t be unique, because there’s seven billion people out there. If I’m thinking it or feeling it, someone else is too. So even if I write something about myself, it’s going to speak for a lot of people, especially when you’re talking about something emotional.

Probably anyone who listens to it is going to be able to relate to it. I mean, I don’t know who Bob Dylan was thinking about when he wrote “You’re a Big Girl Now,” but I do know. I do know because I can apply it to my own circumstance and it makes sense. That’s why he’s a great songwriter.

As far as your own songwriting, do you feel that whatever it was that inspired you or motivated you when you first began writing and performing music still fuels you today? Or has it changed?

Hynde: No, it’s 100 percent exactly the same. And I’m finding that, as I’m sitting down on the floor with a guitar, I’m thinking, I f*cking love this! But I do a specific thing that turns me on: I always find it like a meditation, where you get kind of lost in it.

You get very absorbed in it, and it sort of steadies your mind, and it’s kind of a mental and emotional exercise. And it’s very satisfying. I never sit down to write about a specific thing or have an agenda, but there’s certainly an element of getting it off your chest. And it’s the same as it’s always been.

There’s no audience in the world who loves guitar-based rock and roll more than the American audience

Chrissie Hynde

At the same time, the way that rock and roll is regarded and absorbed by the general public has changed in the years since you started out.

Walbourne: Yeah, guitar music’s not as popular as it was. But if you grew up with it, I think it’s still in your head. I mean, I could have never wanted to be anything else other than a guitar player.

But if kids don’t see that anywhere, it loses a bit of its appeal. It’s sad, isn’t it? But there’s a market for it still. People still want to go and see it, and that’s what we do. I think it’s our duty to keep flying the flag, as it were.

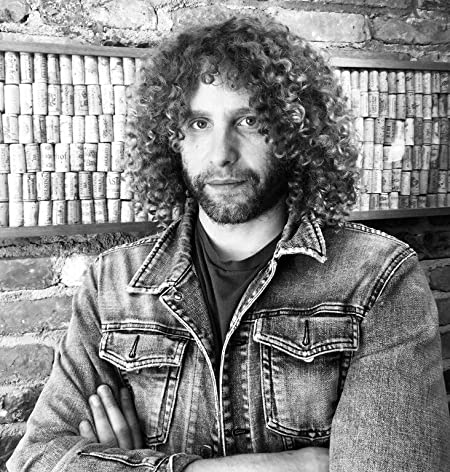

![The Pretenders [L-R]: James Walbourne, founding drummer Martin Chambers, Chrissie Hynde and bassist Nick Wilkinson](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/xjSYhzNPUun4v5ZvKEdZ3S.jpg)

Chrissie, do you think about the state of rock and its place in youth culture?

Hynde: I think about it every day of my life. And it goes through waves where you think nobody wants this anymore. You think it’s a dead form.

And then you do a tour of America and you see an American audience, and there’s no audience in the world who loves guitar-based rock and roll more than the American audience.

I could tour there for years and play every night and we still wouldn’t satisfy the audience. So the people who want this — they are out there. There’s absolutely no doubt about it. They’re bikers and they’re waitresses, and they’re out there, and those are my people. So I have to deliver it.

But from a point of view of making records? You constantly think, Nobody wants this. This is old-fashioned. But then you just say, “F*ck it! I’m sticking to my guns and doing it anyway.

- The Pretenders' new album, Hate for Sale, is out now via BMG.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Rich is the co-author of the best-selling Nöthin' But a Good Time: The Uncensored History of the '80s Hard Rock Explosion. He is also a recording and performing musician, and a former editor of Guitar World magazine and executive editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine. He has authored several additional books, among them Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, the companion to the documentary of the same name.

“We’d heard Jimi Hendrix, we'd heard the Who, but now we finally got to see these guys. And watching Jimi Hendrix burn his guitar….” Grace Slick on Hendrix at Monterey, Jefferson Airplane and the Spanish origins of “White Rabbit”

“I’m still playing but I’m covered in blood. Billy’s looking at me like, ‘Yeah! That’s punk rock!'” Steve Stevens on his all-time worst gig with Billy Idol — and the visit to Jimi Hendrix's grave that never happened