Chaos, Violence and Rock and Roll: the Story of the Rolling Stones' 1969 U.S. Tour

The shows were bigger, louder and more spectacular than ever. But success came with a body count.

It might have been the first rock and roll tour of any real consequence. Today, if it’s remembered at all, it’s usually for the body count left in its wake.

But Bill Wyman recalls the Rolling Stones’ 1969 American tour for a different reason. “In 1969, they listened,” the former Stones bassist says. “It was the first time that the audiences had actually listened to us.”

Woodstock may be the musical event of 1969 that defined a generation, but the Rolling Stones’ 1969 American tour set the standard for the future of rock and roll concerts. Launched in November of that year, a little more than two months after Woodstock, the cross-country jaunt isn’t regarded with the same reverence as the festival.

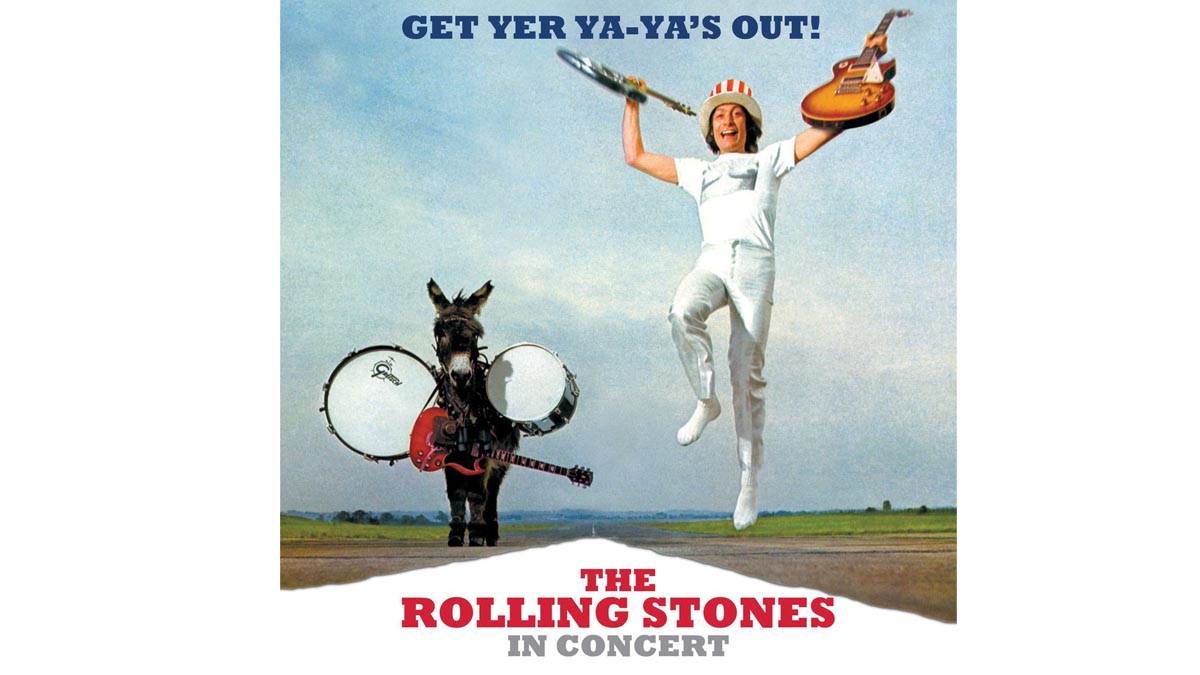

Fans know it as the tour captured on the 1970 release Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out!, the Stones’ second live album and a favorite concert album among those who have sunk a needle into its grooves.

But the group’s U.S. hitch not only changed how rock and roll shows were presented – it also showed a new way to finance them and make a profit, opening the door to the barnstorming extravaganzas launched by artists like Led Zeppelin, Yes, Elton John and others in the 1970s and the decades that followed.

It was, as Wyman notes, the start of a new time, when the fans stopped screaming and began to listen, as well as turn on and become immersed in the live-music experience.

Anyone who witnessed the British Invasion first-hand knows all too well how awful rock and roll concerts could be in the mid 1960s, when primitive sound systems were unable to project a band’s music above the noise of the crowd.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

As a budding guitarist looking forward to a show from your favorite players, you’d have strained to hear their instruments, whose frequency range was well matched to that of the screaming girls.

You’d probably have trouble seeing the band too. Under the glare of stage lights or spots, acts played with little to no staging – no set, no props, no lighting effects. As performances went, it was as rudimentary as it could be.

After sitting through three or four opening acts, the band you’d shelled out your hard-earned allowance to see came onstage and played its hits for 20 to 30 minutes before abruptly departing. The Rolling Stones certainly knew the drill.

Their previous U.S. tour, in 1966, in support of their album Aftermath, opened in Lynn, Massachusetts, where 17,000 fans packed the Manning Bowl for the evening’s entertainment.

The outdoor show opened with the Mods, a local act who had won their spot through the promoter of a battle of the bands contest. They were followed by the McCoys, then riding high on their hit “Hang on Sloopy” and the Standells, the L.A. act whose breakthrough hit, “Dirty Water,” celebrated Boston, Lynn’s neighbor to the south.

Things got a little blurry in the ’60s. Tear gas – that was the other continuous smell of the ’60s. I can’t say I miss it

Keith Richards

The Stones’ set, consisting of a mere 10 songs, lasted just over 30 minutes. That was short enough, but the Manning Bowl show ended early when a rainstorm broke out. Teens stormed the stage, and the police responded with tear gas.

The Stones escaped to their limos and fled. “It was a bit of an outdoor crazy,” Mick Jagger recalls. ”It wasn’t well secured. A few people got a bit drunk. There were a few cops, and that was the end of it.”

“Things got a little blurry in the ’60s,” Keith Richards says. “Tear gas – that was the other continuous smell of the ’60s. I can’t say I miss it.”

But by the decade’s end, much had changed in music and the youth movement. Those screaming teens had grown up. Many were now out on their own, burning their draft cards, marching to protest the Vietnam War, experimenting with drugs and defining their own place in society.

Rock and roll had evolved as well, with bands like the Beatles introducing elements of spirituality in their music, while groups like the Stones met social and political issues head on.

Their 1968 hit “Street Fighting Man” had been embraced by youths in France, who fought in the streets of Paris that May for social reforms, and by young Americans protesting the Vietnam War at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago that August. Older and radicalized, rock and roll fans went to shows, smoked weed, or took something stronger, and actually listened to the music.

Unfortunately, the new arenas and civic auditoriums that began dotting the U.S. landscape in the latter half of the 1960s weren’t suited to rock shows. Vast, with seating for 10 to 20 thousand attendees, they were ill-equipped to handle musical events, their underpowered public-address systems designed for sporting events rather than sold-out concerts.

Fans furthest from the stage weren’t only deprived of the music – the performance itself looked like a distant skirmish under the floodlights.

Remarkably, England’s Rolling Stones would provide the solution to this uniquely American problem. By 1969, nearly three years had passed since the group’s 1966 tour, their last in the United States. At that time, they, along with the Beatles and Bob Dylan, made up pop music’s Big Three.

But the Beatles had stopped performing and were in the midst of breaking up, while Dylan was a recluse in Woodstock. Somehow, the Rolling Stones were still standing, and with a new guitarist in tow – John Mayall’s young blues protégé Mick Taylor – they were ready to claim the field for themselves.

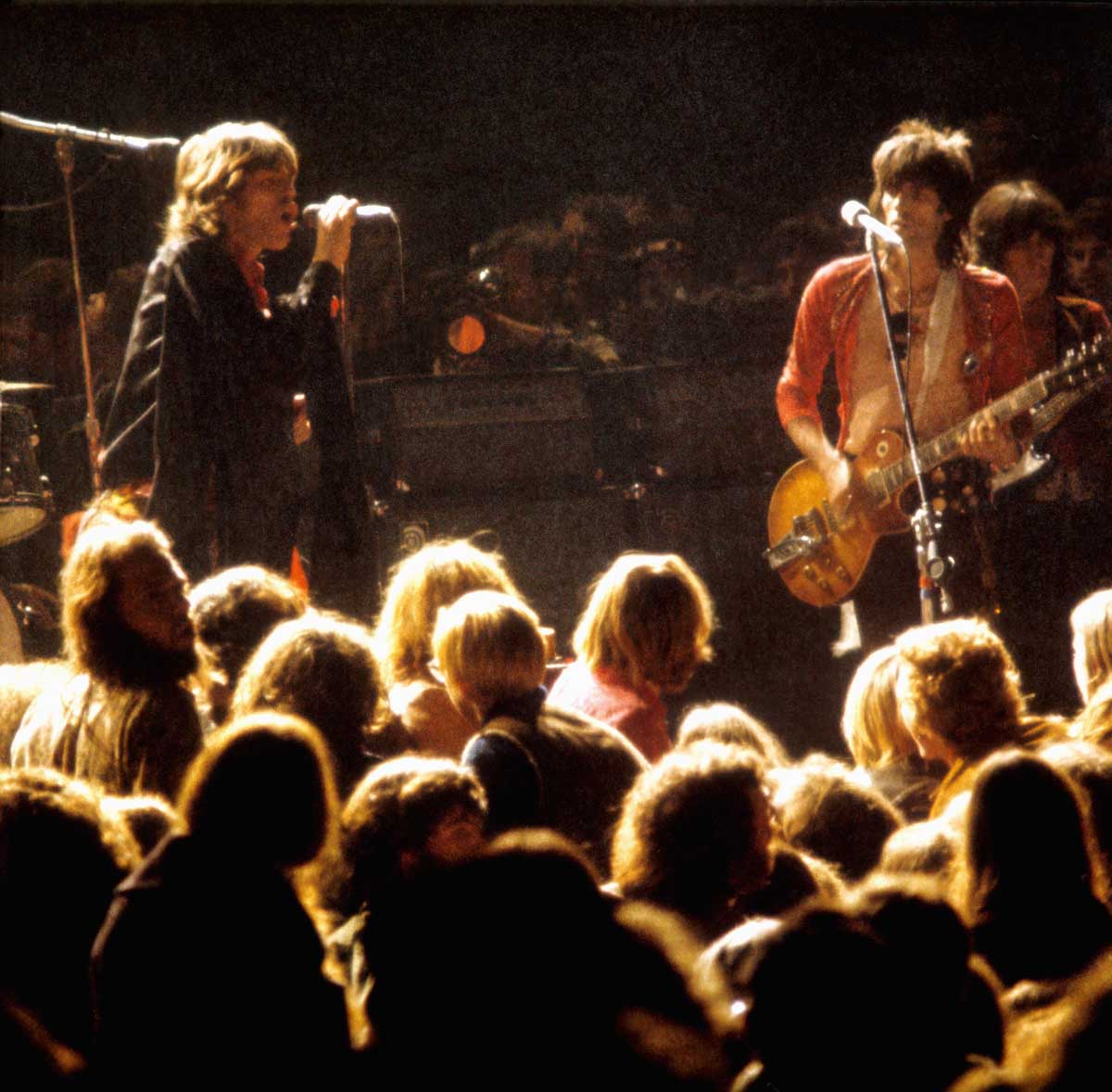

This time they wanted a spectacle – a show that was bigger and louder than before, with proper sound reinforcement and set design.

They hired lighting designer Chip Monck – who lit Monterey Pop and as Woodstock’s emcee warned the festival’s flower children away from the “brown acid” – to create a set that they would haul from stage to stage. They brought their own P.A. system and mixing board, and drafted recording engineer Glyn Johns to run sound and record the shows.

They didn’t trust local promoters, so they chose their own opening acts, bringing along English guitarist and vocalist Terry Reid, and booking a trio of show-stopping American acts: the Ike & Tina Turner Revue, B.B. King and, a guitarist who was like a god to them, Chuck Berry. Significantly, the Stones booked every show themselves, eliminating middlemen and ensuring themselves maximum profits.

The jaunt itself would see Jagger and Richards slip further into hard-drug use. And when it was over in early December, a cloud of death hung over what should have been a celebration

Above all, they wanted to perform. No more 30 minutes of hits. The 1969 American tour saw the Rolling Stones play for an average of 75 minutes each show, with many concerts lasting past midnight.

Everything was designed to draw the audience into the act. Monck designed a proscenium stage backlit with lights that changed color to suit the songs’ moods, and concealed the speaker towers by draping them in grey cloth.

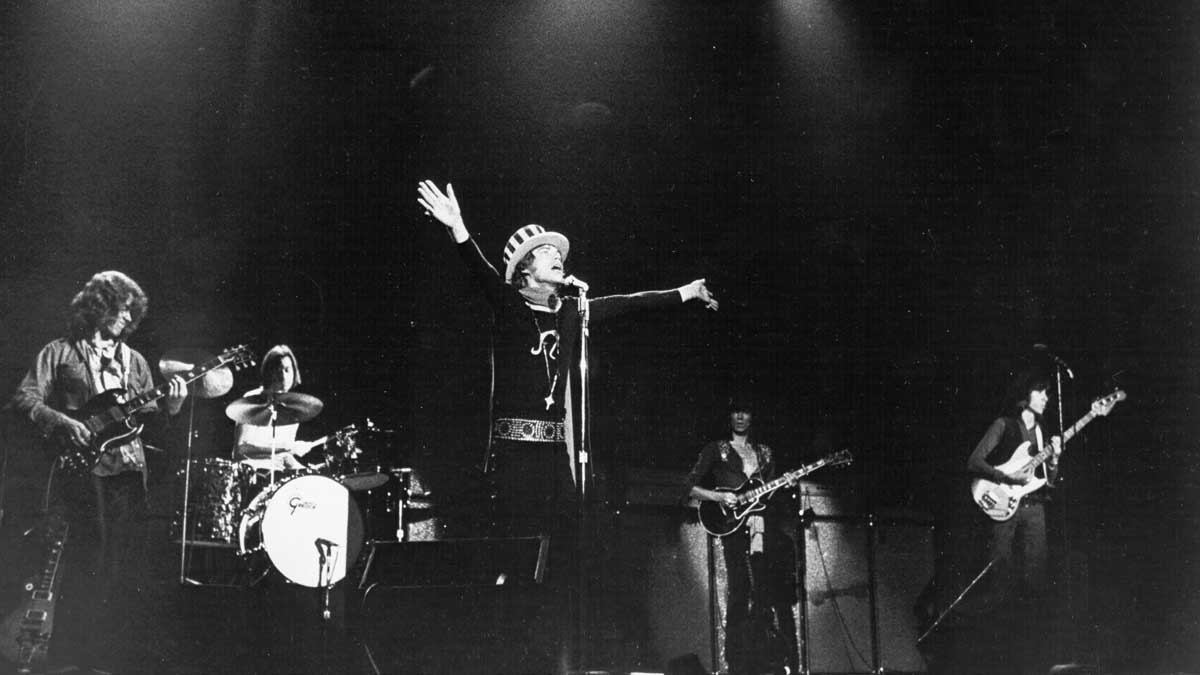

At the center of it all, on a purple carpet with a white starburst center, Mick Jagger led the Rolling Stones – Richards, Taylor, Wyman and drummer Charlie Watts – through the set like a ringmaster, dressed in black trousers with silver buttons down the legs, a metal-studded belt, a black scoop-necked jersey with a white Leo glyph on the chest, a flowing red scarf, and a red, white and blue Uncle Sam top hat.

The 1969 American tour didn’t just reassert the Rolling Stones as a powerhouse rock and roll band – it also changed expectations of what a rock and roll show should be, how it should be run, and the production standards required.

It’s here that the modern music concert tour began. And it’s here that the Rolling Stones’ legend as “the greatest rock and roll band in the world” – as tour manager Sam Cutler introduced them each night – begins.

But getting to this point wasn’t easy. By the time the tour launched on November 7, in Fort Collins, Colorado, one of the Stones’ own would be in the grave. The jaunt itself would see Jagger and Richards slip further into hard-drug use. And when it was over in early December, a cloud of death hung over what should have been a celebration.

The Rolling Stones had always been one of rock and roll’s most exciting live acts, but by 1969, they were rarely seen onstage anymore. Since the group’s 1967 European tour, they had made one public appearance, at the 1968 NME Poll Winners Concert, not including their own Rock and Roll Circus concert from December 1968 before an invitation-only audience. The reason was down to drugs.

Jagger, Richards and Stones co-founder Brian Jones had all been charged with offenses. But whereas Jagger’s three-month sentence for possession of amphetamine tablets was reduced to a conditional discharge – essentially an order to “keep your nose clean” – and Richards’ conviction for allowing pot to be smoked on his property was overturned on appeal, Jones was not nearly so lucky.

Police had discovered cannabis and hard drugs at the multi-instrumentalist’s home during a raid in May 1967.

The following May, while still on probation, he was arrested again after a second raid at his flat turned up hash. Jones was found guilty, but the judge, believing the jury prejudiced, refused to jail the guitarist and instead fined him £50, about $890 today.

Brian and Keith had this guitar thing like you wouldn’t believe. There was never any suggestion of a lead and a rhythm guitar player. They were two guitar players that were like somebody’s right and left hands

Ian “Stu” Stewart

Though Jones had avoided jail, his second drug bust made it impossible for him to get a U.S. work visa, dashing the Stones’ hopes of touring in America. But his days with the group were already numbered.

Though he had been the band’s original leader, Jones’ authority diminished once Jagger and Richards became a successful songwriting duo. As his drug use increased and his mental state became more fragile, Jones missed gigs and recording dates.

A few years earlier, he and Richards had been among the tightest of guitar tandems.

“Brian and Keith had this guitar thing like you wouldn’t believe,” Ian “Stu” Stewart, the band’s co-founder and behind-the-scenes keyboardist, told Stanley Booth, author of The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones. “There was never any suggestion of a lead and a rhythm guitar player. They were two guitar players that were like somebody’s right and left hands.”

But at least since the Stones’ psychedelic-rock opus, 1967’s Their Satanic Majesties Request, Jones had played guitar less frequently.

On the group’s followup, 1968’s Beggar’s Banquet, he contributed slide and acoustic guitar, Mellotron, tambura and sitar, leaving Richards to perform all the other guitar parts. By the time the Stones began recording 1969’s Let It Bleed, they didn’t even expect Jones to attend the sessions.

He showed up for the recording of “You Can’t Always Get What You Want,” asking Jagger, “What can I play?” “I don’t know, Brian,” Jagger replied. “What can you play?” “I enjoyed his company, and I tried incredibly hard, in 1966, to pull him back into the group,” Richards told Rolling Stone in 2010. “He was flying off. But my attempts to bring Brian back into focus were a total failure.”

While the Stones could work around Jones in the studio, they couldn’t do without a second guitarist onstage. They briefly considered replacing him for the U.S. tour with Eric Clapton, but in the end, the Stones faced up to the inevitable.

Mick and I didn’t fancy the gig. But we drove down together and said, ‘Hey, Brian… It’s all over, pal’

Keith Richards

On June 8, Jagger, Richards and Watts drove to Jones’ home, Cotchford Farm, the former estate of Winnie the Pooh author A.A. Milne, to deliver the news. “Mick and I didn’t fancy the gig,” Richards wrote in his 2010 memoir, Life. “But we drove down together and said, ‘Hey, Brian… It’s all over, pal.’”

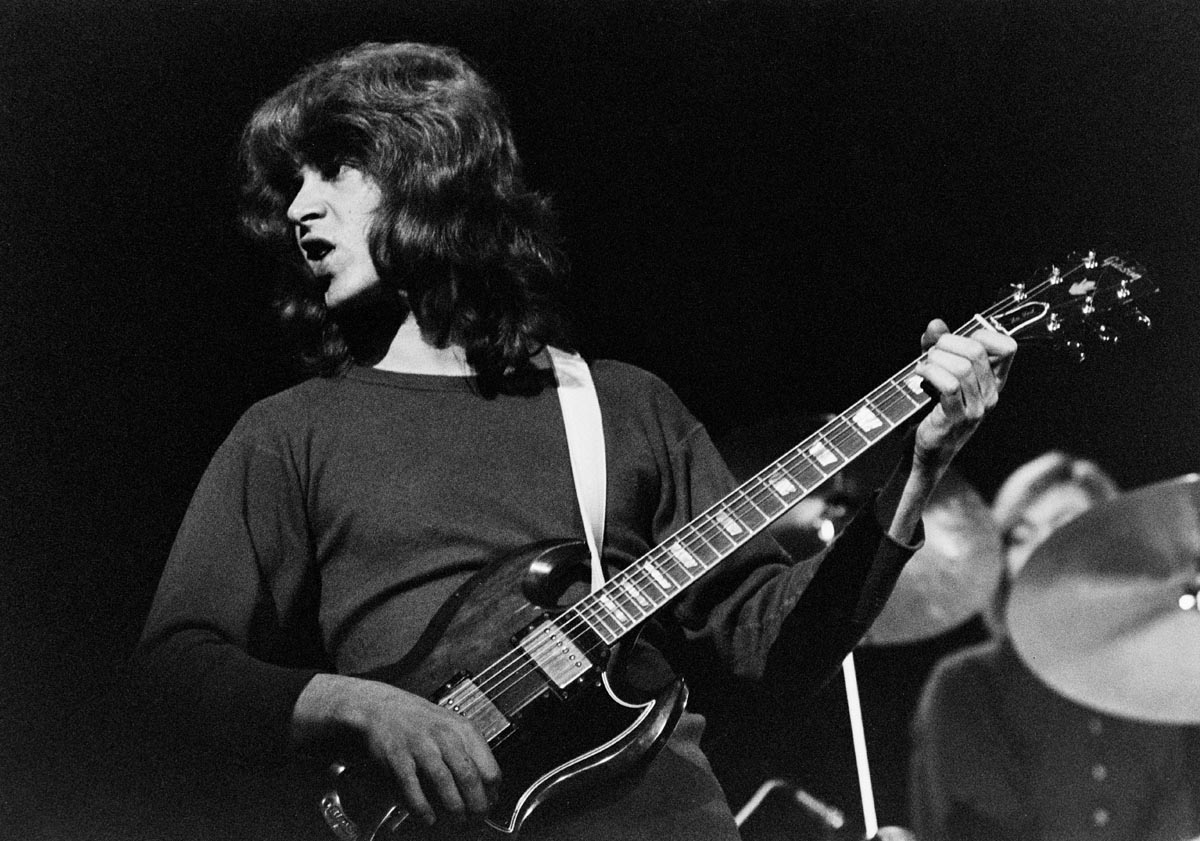

By then, the Stones had found his replacement: 20-year-old Mick Taylor. Despite his youth, Taylor had already distinguished himself in John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, taking over from Peter Green, Clapton’s successor, in 1967, at the tender age of 18. A fine blues guitarist, Taylor was blessed with a jazzman’s sensibilities, his remarkably melodic lead work streaked with shades of modal playing.

It was Mayall and Ian Stewart who suggested Taylor to Jagger and Richards. Certainly, Richards knew Taylor – he’d sold him his 1959 Les Paul Standard back in 1967 when Taylor had joined the Bluesbreakers.

The Stones had taken the young guitarist onboard even before they let Jones go: Though many sources pin the date to June 1969, Taylor’s first recording with the Stones was on “Live With Me,” which was recorded May 24, two weeks before Jones was fired.

The Stones actually hadn’t played together for a long time, so when I joined them it was like a new beginning. It was a new phase in their career. A new chapter

Mick Taylor

“‘Live With Me’ was the very first track I ever played on,” Taylor recalls, “when they were putting the finishing touches to Let It Bleed. We actually recorded that the night I went for my audition at Olympic Studios, or maybe the night after.

“I remember [producer] Jimmy Miller jumping up and down in the control room and getting all excited about how good it sounded, having two guitars playing off each other. Because I think they’d missed that with Brian Jones in the two-year hiatus since their last live performance.

“The Stones actually hadn’t played together for a long time, so when I joined them it was like a new beginning. It was a new phase in their career. A new chapter.”

To kick it off, the Stones had agreed to play a free concert in London’s Hyde Park on July 5. The timing was good: Their new single, “Honky Tonk Women,” featuring the lead guitar work of both Richards and Taylor, was scheduled to be released the day before.

The Hyde Park concert would be an opportunity to show off their new lineup and put some publicity behind the song. But the Stones’ previous chapter was still being written.

Sometime around midnight on July 2-3, Brian Jones was found dead in the swimming pool at Cotchford Farm. Before the sun had risen, the news made its way through the Stones’ camp and into the morning news. Richards recalls that the band members were in the studio when they heard about it.

“There exists one minute and 30 seconds of us recording ‘I Don’t Know Why,’ a Stevie Wonder song, interrupted by the phone call telling us of Brian’s death,” he wrote.

Mick Taylor’s arrival in the Stones marked the start of a new era and sound for the Rolling Stones. Though Jones was a talented guitarist, soloist and multi-instrumentalist, Taylor was in a different league.

Ry was using open G for slide. I saw him and thought, That’s a really nice tuning. It restricts you so much: five strings, three notes, two fingers… one asshole!

Keith Richards

His muscular lead-guitar style fit their new blues-rock direction and brought a level of bravura to their ranks at a time when guitar virtuosity was on the rise in rock and roll.

“I was in awe sometimes, listening to Mick Taylor,” Richards wrote. “Everything was there in his playing – the melodic touch, a beautiful sustain and a way of reading a song.” Taylor’s melodicism proved a perfect counterpoint to Richards’ own recently adopted style.

In March 1969, during the making of Let It Bleed, the group had recorded “Sister Morphine,” a track destined for 1971’s Sticky Fingers, with Ry Cooder playing slide. Richards was taken with Cooder’s use of open-G tuning and adopted it as standard for his guitar work, eliminating his low E string in the process.

“I met Ry in 1968, when he was hanging around with Taj Mahal and Jesse Ed Davis,” Richards told Guitar. “Ry was using open G for slide. I saw him and thought, That’s a really nice tuning. It restricts you so much: five strings, three notes, two fingers… one asshole!”

With their reconstituted lineup and tough new guitar sound, the Stones were eager to get back onstage. The fans were clamoring for it. Seven years into their career, the Stones sounded better than ever. Just as important, they were still relevant.

As rock and roll’s bad boys, they had always had an element of danger about them, but it was more overt on their newer material, like “Sympathy for the Devil,” the Beggars Banquet opener, on which Jagger adopted Satan’s persona to implicate humanity in the world’s sins, placing the weight of social responsibility on the shoulders of the Stones’ young radicalized listeners.

On the album’s flipside, “Street Fighting Man” offered a model for how to effect the change necessary to liberate a world stuck in the ways of the past and running headlong to its own destruction.

Teenagers are not screaming over pop music anymore. They’re screaming for much deeper reasons

Mick Jagger

The Stones had won the love of politically minded youths with those songs, but Jagger glimpsed what was to come as early as 1967, when they played Warsaw, Poland, bringing rock and roll to Communist Eastern Europe.

“Teenagers are not screaming over pop music anymore,” he told Stanley Booth. “They’re screaming for much deeper reasons. When I’m onstage, I sense that the teenagers are trying to communicate to me, like by telepathy, a message of some urgency. Not about me or about our music, but about the world and the way they live. And I see a lot of trouble coming in the dawn.”

In September, the Stones began making plans for their month-long jaunt across America. Following an off-circuit gig on November 7 at Colorado State University’s 8,745-seat Moby Gymnasium, the tour would commence in earnest.

The itinerary would take the show from Los Angeles up to Oakland, across to Phoenix, down to Dallas and over to Alabama, before heading north to Chicago and east to Detroit, Philadelphia, Baltimore, New York City and Boston, the final stop.

As shows sold out in the larger cities, the Stones added second shows, though Mick Jagger, ever cautious about the cost, warned, “We won’t play if there’s a single empty seat.”

The Rolling Stones wanted to control everything, from signing up and paying the opening acts to designing the production. “There was one minor problem, though,” said Ronnie Schneider, the tour’s manager. “We had no money, nothing.”

The William Morris Agency had signed on to book the tour, but the Stones’ preeminence made its role moot. In the end, William Morris put up just $15,000 “to finance a half-million-dollar tour,” Schneider says. “To pay for the construction of the set, the stage, the lights, to guarantee the acts, to do everything. It was a very funny moment.”

But Schneider came up with a solution that was revolutionary. In his scheme, the Stones – or rather, their new company, Rolling Stones Promotions – would receive, upfront, 50 percent of each venue’s gross box-office receipts, which would be used to fund the tour.

Any problem with any of them and the shit was hitting the fan

Ronnie Schneider, tour manager

Jagger’s insistence on sold-out shows wasn’t about ego but to generate demand for future shows to keep the tour running. For the scheme to work, they’d need to sell out the first five dates. “Any problem with any of them and the shit was hitting the fan,” Schneider said.

Not only did the gambit work – it changed how bands financed tours, allowing them to launch ever-greater spectacles. Schneider also led the way by taking over managing rights related to all aspects of the tour, including posters, T-shirts and programs, eliminating freelance merchandisers and greatly improving the Stones’ finances.

But all was not well in this new world of mega shows. Soon after the tour was announced, fans began to complain about the size of the venues and ticket prices. Rolling Stone noted that tickets for the Los Angeles Forum show ranged in price from $5.50 to $8.50, whereas the same arena had charged $3.50 to $7.50 for Blind Faith and $3.50 to $6.50 for the Doors.

Writing in The San Francisco Chronicle, Rolling Stone founding editor Ralph Gleason took the Stones to task for asking fans to pay more to see them perform in less-intimate settings.

“Paying five, six and seven dollars for a Stones concert at the Oakland Coliseum for, say, an hour of the Stones seen a quarter of a mile away...says a very bad thing to me about the artists’ attitude towards the public,” Gleason wrote. “It says they despise their own audience.”

Gleason’s words stung the band. Confronted about the matter at the tour’s first U.S. press conference, Jagger left the door open to playing a free concert when the jaunt was over.

Weeks later, in New York City, he confirmed the group would headline a free show in the San Francisco area. Why San Francisco?

“Because there’s a scene there,” Jagger replied. “And the weather’s nice.”

From London, the group flew to Los Angeles in October to begin rehearsing and preparing for the tour. Immediately, the members split into different residences.

Bill Wyman and his wife rented a home, while Charlie Watts, with his wife and child in tow, stayed in a large hotel-like home on Oriole Street – dubbed Oriole House – where the group’s entourage of staff members and handlers oversaw preparations for the tour. Jagger, Richards and Taylor found privacy at Stephen Stills’ house in Laurel Canyon.

The abode gave Jagger and Richards a place to work on tunes for the group’s next album, and afforded Richards and Taylor a chance to work out their arrangements for the songs selected for the tour. The home’s cramped coffin-shaped basement also doubled as the band’s practice space.

“We did some rehearsals,” Wyman recalls. “We didn’t do a lot. You know what the Stones are like. It was mostly party time.” Mick Taylor, new to this world, was shocked to find the Stones’ sound so “ragged.”

“I thought, How do these guys make such great records when they’re so sloppy and spontaneous? But it was because they had this great chemistry.”

I thought, How do these guys make such great records when they’re so sloppy and spontaneous? But it was because they had this great chemistry

Mick Taylor

Developing the set list proved more difficult than they’d imagined. While the stylistic differences between the new guitar duo made for some great interplay – Richard’s jagged double-stop riffing against Taylor’s sinewy blues lines – it made playing most of the old hits impossible without some degree of reinterpretation.

From the Stones’ deep back catalog, only three songs – “Under My Thumb,” “I’m Free” and “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” – were dusted off and recalibrated for the new lineup. Mostly, the band focused on their latest hit singles – “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” and “Honky Tonk Women” – and cuts from Beggar’s Banquet and the still-unreleased Let It Bleed.

The bluesier country stylings of those albums gave Taylor plenty of room to stretch out and play bottleneck slide, something Jones was also adept at, though not with the same burning intensity.

For good measure, they tossed in a couple of Chuck Berry standards – “Carol” and “Little Queenie” – to showcase Keith’s driving double-stop riffs. Unfortunately, Stills’ basement was too small to hold rehearsals with full gear.

Through their connections, the Stones secured an unused soundstage at Warner Bros. studio lot. The building chosen for them had served as the main set for director Sydney Pollack’s 1969 Depression-era drama They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?, starring Jane Fonda and Michael Sarrazin as a couple who compete in a grueling dance marathon for the chance to win $1,500.

Though filming had been completed, the film’s elegant 1930s-style ballroom set was still up when the Stones arrived. Above it hung a large scoreboard that, in the film, shows how many hours have elapsed in the marathon and the number of couples still standing.

“How Long Will They Last?” read a legend at the top of the board. For the Stones, binging on drugs and rushing headlong into a tour for which they were unprepared, the question was perversely appropriate.

Prototype SVTs hadn’t been field tested, making Richards and Taylor unwitting guinea pigs in the amp’s development. Ampeg sent a pair of techs to maintain them, along with five additional backup units

For the short tour, Richards and Taylor were well equipped with guitars and amps. According to gear expert Andy Babiuk, Richards’ main guitars were his prototype Ampeg Dan Armstrong Plexiglas and a 1958 Gibson Les Paul Custom he’d purchased earlier that year. His other guitars on the tour included his 1969 Gibson ES-355TD-SV stereo electric and the 1959 Les Paul Standard he’d sold to Mick Taylor in early 1967.

In addition, Richards brought a 1930s National Style O resonator, which he used when performing “Prodigal Son” and “You Gotta Move” with Jagger in the show’s short acoustic set, and a Martin D12-20, a dreadnought-sized 12-string, fitted with a DeArmond soundhole pickup.

As for Taylor, he mainly used his Cherry Red 1961 Gibson Les Paul SG, whose “sideways” tremolo unit he’d replaced with a Bigsby B-5. He also occasionally used the ES-355TD-SV and his ’59 ’Burst for slide, as well as his 1958 Les Paul Standard. For amps, both guitarists were provided an arsenal of Ampeg’s new prototype SVT – Solid Vacuum Tube – amps.

The Stones had shipped their Hiwatts from England, but the amps were damaged after they arrived stateside. Ian Stewart, who recalled that the group had used an Ampeg B-15 Porta-flex “flip-top” amp in its early recording sessions, contacted the manufacturer in New Jersey, and the company quickly sent along a truckfull of SVT prototypes, along with some ST-42 4x12 guitar cabinets from Ampeg’s solid-state line.

Designed as bass amps, the SVTs put out a whopping 300 watts, prompting Ampeg to place a warning label on early models. A dozen prototypes were built, most of which were loaned to the Stones.

The Ampegs were first used when the group moved to the Warner Bros. soundstage, although photos from those sessions show Taylor using several Fender Twin Reverbs. On tour, he, like Richards, performed before an impressive wall of SVTs.

Unfortunately, the prototype SVTs hadn’t been field tested, making Richards and Taylor unwitting guinea pigs in the amp’s development. Ampeg sent a pair of techs to maintain them, along with five additional backup units.

Not only were the amps not designed for electric guitar but Richards and Taylor were using two or three simultaneously. The techs would sit onstage, behind the amps, and watch the tube plates for signs of overheating, then swap out an amp before it blew. They weren’t always successful.

At the Oakland Coliseum on November 9, the second date of the tour, Richards’ amp failed during the intro to “Jumpin’ Jack Flash,” the second song of the show.

He and Jagger quickly switched to the acoustic portion of the set while the situation was remedied, but when Richards plugged back into the amp, it blew again, causing him to smash his Les Paul Custom in anger.

The Grateful Dead, who were working with the Stones on arranging the free concert in San Francisco, came to the rescue by loaning their amps for the remainder of the show.

The tour was well received by fans and the press throughout its run, although critics noted early on that the opening acts – particularly B.B. King and the Ike & Tina Turner Revue – were remarkably more polished than the Stones.

“At the beginning of the tour, the band was rusty,” Sam Cutler told photographer Ethan Russell for Let It Bleed, Russell’s photobook of the tour. “When I first called them ‘the greatest rock and roll band in the world,’ I meant it sarcastically. In a way, the slogan made them work harder right from the start.”

By the time the circus rolled into New York City’s Madison Square Garden for the November 27 and 28 dates, the Stones were deadly. It’s from these performances that the group culled the tracks for Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out!, with one song – their affecting cover of Robert Johnson’s “Love in Vain” – taken from the November 26 show at Baltimore’s Civic Center.

The Stones’ tough new sound and attitude are evident right from the album’s opening cut. “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” was the hot hit the band would have toured on had they been on the road when it was released in the summer of 1968. More than a year later, it was a hard-wearing fan favorite.

When I first called them ‘the greatest rock and roll band in the world,’ I meant it sarcastically. In a way, the slogan made them work harder right from the start

Sam Cutler

The band plays it faster on the live album, and in the key of B, whereas the single sounds slightly flat of the key of B flat. And while, on the studio version, Bill Wyman holds down a pedal point on the verses, he plays along with the guitar riff on the live cut, eliminating the single’s hip-swinging groove and making the song a foot-stomping blues-rock number, a genre shift underscored by Taylor’s delicious climbing lead lines on the song’s chorus.

Taylor mostly lays back on the next track, Berry’s “Carol,” giving Richards room to display his classic rock and roll chops. Though he mostly shadows Richards’ rhythm work, the young guitarist steps out on the song’s signature riff, playing bluesy descending lead lines that add interest.

He gets a chance to show his stuff on “Stray Cat Blues,” squeezing fast, stinging lead lines from his guitar during the song’s numerous instrumental breaks. This funky Beggar’s Banquet cut gets new life here.

Taken at a slower and bluesier pace, and with a less busy arrangement, the live version draws much of its power from Jagger’s sexually charged vocals. His singing on the studio version is loose and strung out, but on the live album he taunts, pleads, threatens and reprimands as he expounds on his proposition, imbuing it with a menacing authenticity the studio version lacks.

The fact that the song is about seducing a child – 15 years old on Beggar’s Banquet, reduced to 13 in concert – makes his aggressive performance all the more disturbing. Taylor’s first big moment in the spotlight comes on “Love in Vain,” where he switches to his 1959 ’Burst and takes up his slide.

The Stones recorded this Robert Johnson track for Let It Bleed earlier that year, adapting it as a country blues, complete with mandolin, but here it takes on a worn-in urban melancholy, demonstrating how far they’d already progressed as interpreters of classic blues.

The sessions for that album were not far behind them, but on this November 26 evening in Baltimore, they sound like they’ve endured miles of hard road.

The next night, backstage at Madison Square Garden, Jagger would learn that his girlfriend was leaving him and his lover was pregnant with his child, but in Baltimore he sings the tune as if he’s had a vision of the trouble ahead.

Richards’ lovely, arpeggiating guitar work sets the mood for the singer’s lament, but it’s Taylor who expresses the song’s loss and anguish in his slide work, each perfectly chosen and articulated note dancing along its nerve. Simply stellar, “Love in Vain” is one of the best representations of the Rolling Stones’ power as a live act at this stage in their career.

From there, it’s on to what has to be the definitive version of “Midnight Rambler.” The song was unknown to audiences at the time, but at Madison Square Garden they responded reflexively to its shifting moods and momentum, demonstrating how completely the Stones had them in their hands.

Mid-song, the band breaks down the beat, giving Richards and Taylor an opportunity to trade-off licks while Jagger scats. The crowd is amped up, howling, needing an outlet for its agitation.

And it comes: “Well, you’ve heard about the Boston,” Jagger snarls, and the band slams the downbeat, prompting one amazed fan to cry out, “God-damn!”

During the song, Jagger would take off his studded belt and use it to whip the stage, “The moment you saw the belt fall, you could actually hear the crowd go, ‘Ahhh!’” Chip Monck recalls. “That’s when you know you got it. That’s when it’s real.” The song rides out on Taylor’s insistent riffing, and by the time it’s over, nine minutes after it began, the exhausted audience is roaring for more.

As with “Midnight Rambler,” a crowd member gets a cameo on “Sympathy for the Devil,” with a stoned female fan calling insistently for an oldie but goodie. “‘Paint It Black’! ‘Paint It Black,’ you devil!” she demands in vain as the Stones kick into their Beggar’s Banquet hit.

The sinewy Latin feel of the original is abandoned for a boogie-rock rhythm that’s more in keeping with the show’s road-worn vibe. Richards plays his lead lines with a cocaine-fueled itch, relying on nerves and muscle memory as he builds the song to its first peak.

From there, Taylor steals the show, testing the water with country-blues riffs before cutting loose, to the obvious satisfaction of Jagger, who yells his approval and relinquishes the spotlight to the young guitarist. Taylor has one of his finest moments on “Sympathy for the Devil,” lifting the song to new heights.

Richards turns in his signature riffing and lead work on “Live With Me,” the standout Let It Bleed track that marked Taylor’s debut with the group. The Stones attack the song with fury and efficiency, driving its irresistible rhythm with a solid performance that goes straight for the jugular.

From there, it’s onto the second Chuck Berry song of the night, “Little Queenie,” a fun, midtempo rocker that the Stones dispatch with druggy punk attitude. Watts has trouble finding the “one,” and Richards’ can’t seem to shake off the riff nagging in his fret hand.

Ian Stewart’s boogie-woogie piano lines and Jagger’s playful delivery carry the song aloft, but it’s an otherwise uninspired turn. Likewise, “Honky Tonk Women,” the Stones’ most recent hit and certainly a standout moment in the band’s 1969 set, is played too strictly to the original recording, and too slow at that.

The same can’t be said of the album’s thunderous closing track, “Street Fighting Man.” Like “Jumpin’ Jack Flash,” it’s stripped of its pop pretensions and flayed with proto-punk fury, the Stones riding it like a tank over enemy lines and flattening everything in its path.

Throughout the show, Glyn Johns sat in a rented Hertz truck three floors below Madison Square Garden, at ground level, capturing every moment of the shows on tape.

“I was in the truck,” he recalls, “and at one point – probably at the end of the show – I thought there were people stomping on the roof, because the whole bloody truck was bouncing up and down. “So I jump out and I look around. But there’s nobody on top of the truck. The whole building, all of Madison Square Garden above me, was moving. I was petrified.”

The whole building, all of Madison Square Garden above me, was moving. I was petrified

Glyn Johns

Had the Rolling Stones headed home after the tour wrapped in Boston, the furor over ticket prices likely would have died down, snuffed out by the release of Let It Bleed one week later, on December 5. Instead, they spent their last week in America making nice with their fans and recording tracks for their next album at Muscle Shoals.

The first stop was the West Palm Beach International Music and Arts Festival, on November 30, in Jupiter, Florida. The Sunshine State’s attempt at a Woodstock-style event, the festival featured Jefferson Airplane, Janis Joplin, Sly and the Family Stone, the Byrds and several other rock groups, with the Stones scheduled as the closing act.

Rain and a badly timed cold front made the event uncomfortable for fans, and transportation issues delayed the Stones’ arrival by 11 hours. They finally took the stage at 4 a.m. From Florida, the group headed to Muscle Shoals Sound Studio in Sheffield, Alabama, hoping to capture some of their newfound fire on tape.

Over three days, they cut three tracks – their new songs “Wild Horses” and “Brown Sugar,” along with the traditional Black spiritual “You Gotta Move” – all of which were destined for their next studio album, 1971’s Sticky Fingers. And then it was onward to San Francisco and the Saturday, December 6 free concert they’d been railroaded into headlining.

From the start, the organizers had trouble finding a location. San Jose State University’s practice field, the site of an earlier three-day free festival, was selected, but the city, still reeling from that event, refused to issue the necessary permits.

Golden Gate Park was up for consideration, but an NFL football game at Kezar Stadium, situated in the park, on the same day made the location unsuitable.

Sears Point Raceway, in Sonoma, was selected, but the venue’s owner, the television and film production company Filmways, Inc., wanted the Stones to put up $300,000 cash as a deposit. The company also demanded distribution rights for a concert film of the event.

On December 4, with just two days to spare, the Altamont Raceway, in Tracy, 70 miles east of San Francisco, was selected. The festival would open with West Coast groups – Santana, Jefferson Airplane, the Flying Burrito Brothers, the Grateful Dead and Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young – while the Stones served as the closing act.

With memories of Woodstock still fresh, the organizers anticipated a peaceful concert, which is perhaps why no one thought it a bad idea to hire members of the Hells Angels motorcycle club to help out.

The Jefferson Airplane and Grateful Dead had suggested having them on hand, and the Stones concurred. It probably helped that they had enlisted a British group of motorbike fans called the Hells Angels to provide security the previous June at their Hyde Park show, where Mick Taylor made his official debut as a member of the band.

For the promise of $500 in beer, the Hells Angels agreed to keep fans from climbing onto the Altamont’s makeshift stage, which was just one meter high, and provide assistance to attendees, such as giving directions to bathrooms and medical tents.

The concert started out fine, with Santana turning in an inspired set. But as the day progressed, the Angels got drunker, while the young attendees grew more stoned and unruly. The bikers frequently waded into the throng, swinging fists, pool cues and motorcycle chains, to drive back fans or take down flailing, strung-out revelers.

When Jefferson Airplane’s Marty Balin attempted to break up a scuffle, one of the Angels punched the singer, knocking him out. The Grateful Dead had been scheduled to play between CSN&Y and the Stones, but when they arrived and learned what had happened to Balin, they panicked and fled.

The violence was incredible. I thought the show would have been stopped, but hardly anybody wanted to take any notice

Keith Richards

By the time the Stones went on, darkness had fallen and some 5,000 fans were swarming the front of the stage. Jagger, who’d been punched in the face by an attendee when he first arrived, implored the crowd to “cool out.”

They began playing “Sympathy for the Devil” but stopped when the Angels launched another skirmish. “The violence was incredible,” Richards recalls. “I thought the show would have been stopped, but hardly anybody wanted to take any notice.”

The Stones continued to play, having little recourse and hoping the performance would keep the crowd from becoming more chaotic. They launched into “Under My Thumb,” but as Jagger began singing, another fight broke out.

A young man in a lime-green suit was seen tangling with some Hells Angels, when he suddenly pulled a revolver from his jacket. The bikers descended. Hells Angel Alan Passaro reportedly stabbed the man five times with a large knife, while the others stomped him and left him to die.

Attendees carried his limp body to a medical tent, but 18-year-old Meredith Hunter succumbed to his injuries, one of four people who died that day at Altamont.

After the shock of Altamont, the Rolling Stones had given little thought to releasing an album from their U.S. jaunt. But in December, shortly after the tour’s conclusion, a bootleg of their troubled November 9 Oakland Coliseum show began making the rounds at head shops and independent record stores.

Titled Live’r Than You’ll Ever Be, it was one of the earliest commercially sold bootleg albums, along with Kum Back, featuring session recordings from the Beatles’ yet-unreleased Let It Be project, and Great White Wonder, offering uncollected recordings of Dylan’s performances from 1961 through his 1967 sessions with the Band.

The Stones’ bootleg sold very well, which may have influenced the group to release a concert record of its own. Ethan Russell, the tour’s trusted photographer, was hired to shoot its cover.

He created a still life consisting of Jagger’s Uncle Sam top hat and various other elements of his stage costume, along with his passport and odds and ends. Prominently positioned on the hat’s brim was a fat white joint. Jagger, still smarting from the band’s drug busts, looked at the photo in disbelief. “Didn’t you shoot any without the joint?” he asked. Russell had not.

In early February, Charlie Watts was dispatched to a section of the M6 motorway in Birmingham, England, along with a donkey and pieces of the Stones’ gear, including Keith Richards’ Ampeg Dan Armstrong guitar and Mick Taylor’s 1958 Les Paul ’Burst.

He was photographed in his white stage clothes, wearing Mick Jagger’s top hat, and leaping into the air while holding the guitars aloft. Shot by David Bailey, the photo was inspired by the line “Jewels and binoculars hang from the head of the mule,” from Dylan’s “Visions of Johanna.”

Altamont – it could only happen to the Stones

Keith Richards

On Watts’ T-shirt, an image of a woman’s bare breasts provided a visual reference for the album’s title, itself derived from the Blind Boy Fuller tune “Get Your Ya Yas Out,” though in Fuller’s song, ya yas is a euphemism for ass.

The Stones, as always, had no qualms about pushing the limits. Released on September 4, 1970, Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out! quickly became a hit, reaching Number One in the U.K. and Number Six in the U.S., where it eventually went Platinum.

Critics praised it, with Rolling Stones’ Lester Bangs saying, “I have no doubt that it’s the best rock concert ever put on record.”

But for all its success, Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out!, along with the tour that gave birth to it and the innovations the Rolling Stones brought to rock and roll’s live music scene, lie in the shadow of what Keith Richards called “the terrible murder going on in front of us.”“Altamont,” he said in 1971. “It could only happen to the Stones.”

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.